Mitochondrial diseases can be passed from mothers to their children in DNA.

JGI/Tom Grill/Getty Images/Blend Images

hide caption

toggle caption

JGI/Tom Grill/Getty Images/Blend Images

Last fall, the New York-based reproductive endocrinologist John Zhang made headlines when he reported the birth of the world’s first “three-parent” baby — a healthy boy carrying the blended DNA of the birth mother, her husband and an unrelated female donor.

The technique, called mitochondrial replacement therapy, allowed the 36-year-old mother to bypass a defect in her own genome that had led, twice before, to children born with Leigh syndrome, a devastating neurological disorder that typically culminates in death before age 3.

While heralded in many circles as a breakthrough, the news triggered numerous ethical and scientific questions, many of which remained unanswered at the time. Last week, Zhang and his colleagues at the New Hope Fertility Center provided some answers — and raised yet more concerns.

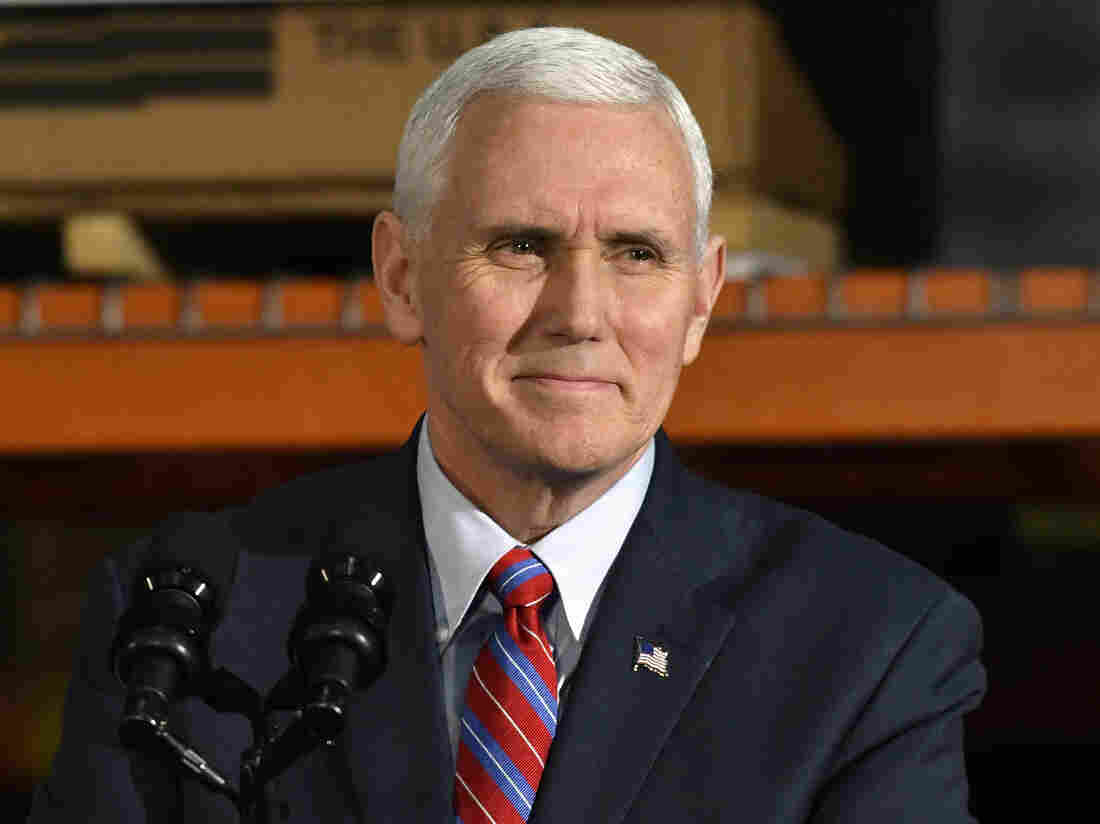

John Zhang of the New Hope Fertility Clinic in Manhattan performed the procedure that used DNA from three people to create a baby boy.

Courtesy of the New Hope Fertility Clinic

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of the New Hope Fertility Clinic

Their new report, published in the journal Reproductive BioMedicine Online, describes both the technique and the participants in greater detail, something that fellow researchers had demanded in order to properly scrutinize Zhang’s methodology.

But in publishing the new material, the journal editors themselves also noted that Zhang’s report still contains “weaknesses and limitations in a number of areas,” including lingering questions about informed consent, the full risks of mitochondrial replacement therapy and the long-term health of the child.

“Although we were able to encourage the authors to include more details of their work in the submission,” journal editor and clinical embryologist Mina Alikani noted in an accompanying editorial co-written with her colleagues, “some uncertainties concerning methodologies and results still remain.”

In a statement provided by the New Hope facility, Zhang conceded that more work needs to be done. “There is always concern about any new procedure and innovation implemented on humans,” Zhang said. “We agree that there are still a lot of unknowns about this technique and will make every effort to monitor the boy’s ongoing progress and test for any adverse outcomes.”

A key weakness in Zhang’s work, according to critics, is that the procedure is not approved in the United States, which forced the team to undertake the procedure in Mexico. “This particular experiment is being done almost entirely outside the normal regulatory structure,” says bioethicist and pediatrician Jeffrey Botkin of the University of Utah, who participated in an Institute of Medicine committee last year that issued a call for more animal research on mitochondrial replacement therapy.

Without proper oversight, Botkin says, vital questions about the technique, as well as the impact of such experiments on resulting embryos, remain difficult to answer.

As it stands, Congress last year prohibited the Food and Drug Administration from considering applications for research in this area, but in December the U.K.’s Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority agreed to let clinics apply to try the procedure on a case-by-case basis. In March, it granted a license to carry out the first procedure to Doug Turnbull, director of the Wellcome Trust Center for Mitochondrial Research at Newcastle University.

“We’re going to look to those in Britain,” Botkin says, “to do careful trials and help us better understand how this technique works.”

In broadest terms, Zhang and his colleagues lifted the nucleus out of the egg of the original mother, leaving behind most — though not all — of her defective mitochondria, which would have led to the almost certain development of Leigh syndrome in the fetus. They then placed that nucleus inside a healthy donor woman’s egg, whose own nucleus had been removed. The result was a hybrid egg with the original mother’s nuclear genes and the donor mother’s cytoplasm and mitochondria. The hybrid egg was fertilized by the father’s sperm and implanted in the birth mother.

The technique could potentially prevent a wide range of mitochondrial diseases, ranging from hereditary blindness to progressive muscle wasting.

A key problem, however, is that not all of the defective mitochondria can be eliminated. The boy, Zhang reports in the new paper, currently carries between 2.36 and 9.23 percent of potentially defective DNA, according to sampling of his urine, hair follicles and circumcised foreskin.

“That’s not surprising,” says Doug Wallace, head of the Center for Mitochondrial and Epigenomic Medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study. “As far as I know, very few cases have been found where there is absolutely no carryover of mitochondria from the donor nucleus.”

Even at a 9 percent load of defective DNA, Wallace said, most people with Leigh Syndrome will appear normal. He added that while it is unlikely, levels could be higher in the boy’s other tissues, such as the brain or heart.

Zhang and his team report that physical examination of the boy has included detailed neurological investigation at regular waypoints, including at two weeks, four weeks, two months, three months and four months. All have proved normal, Zhang said, and the boy is still under close monitoring with “a long-term follow-up plan.”

Just what such a long-term plan might look like, however, is uncertain — particularly given that the parents have publicly said that they do not plan to have the boy regularly tested throughout his life to monitor levels of the errant DNA. University of California molecular biologist Patrick O’Farrell, who was not involved in the Zhang study, suggested that this was worrying, given that there could a rising load of mutations as the boy ages.

In this case, a total five eggs underwent the transfer and were fertilized, Zhang and his team reported. The embryo that was ultimately implanted carried about a 5 percent load of the defective DNA, but the researchers did not examine how much defective DNA was carried over in the embryos that were not used.

The remaining fertilized eggs are still available, says Zhang, but he has not tested them to see how much defective DNA each contains. Should the parents decide they’d like to have another baby, Zhang said he would test the others.

Still, without readily accessible data on the transfer of defective DNA in all of the fertilized eggs, O’Farrell argues that important insights are being overlooked. A three-parent baby, he said, offers the rare chance to study the “segregation and transmission of mitochondrial genomes.”

In a telephone interview, Zhang emphasized that analyses are ongoing. “This is new ground, so there are many questions to ask and more studies to come,” Zhang said. “With new tests in new studies, we will continue to learn more.”

For all of the lingering questions, Zhang’s groundbreaking research has sparked a flurry of similar research elsewhere. The editors of the journal carrying his new report credit Zhang with helping to nudge “cautious use” of mitochondrial replacement therapy in the U.K. Meanwhile, the fertility specialist Valery Zukin has used the three-parent technique in the Ukraine to help two infertile women who suffer from a syndrome known as embryo arrest, where their fertilized eggs stop growing before they can be implanted in the uterus.

Both women gave birth to apparently healthy babies this year.

Such news will surely be welcomed by desperate parents looking for new ways to conceive, but experts like O’Farrell continue to worry that the procedure is being deployed too quickly, and with too many question unanswered.

“I feel like extending this work into infertility cases is dangerous,” O’Farrell says. “For every gene that compromises fertility, we need to know whether it also is going to affect later aspects of development.

“If you only rescue fertility,” he adds, “the other defects that gene might cause will still be there.”

Jill Neimark is an award-winning science journalist and an author of adult and children’s books. Her most recent book is The Hugging Tree: A Story About Resilience.

A version of this articleoriginally appeared at Undark, a digital science magazine published by the Knight Science Journalism Fellowship Program at MIT.

Let’s block ads! (Why?)