Oklahoma Wanted $17 Billion To Fight Its Opioid Crisis: What’s The Real Cost?

State’s attorney Brad Beckworth lays out one of his closing arguments in Oklahoma’s case against drugmaker Johnson & Johnson at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla. in July. The judge in the case ruled Monday that J&J must pay $572 million to the state.

Chris Landsberger/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/AP

Today, the judge hearing the opioid case brought by Oklahoma against the pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson awarded the state roughly $572 million.

The fact that the state won any money is significant — it’s the first ruling to hold a pharmaceutical company responsible for the opioid crisis.

But the state had asked for much more: around $17 billion. The judge found the drugmaker liable for only about 1/30 of that.

“The state did not present sufficient evidence of the amount of time and costs necessary, beyond year one, to abate the opioid crisis,” Judge Thad Balkman wrote in his ruling.

That’s the big reason for the discrepancy. The judge based his decision on one year of abatement. The state’s plan — and the basis of that $17 billion ask — was looking at abatement for the next three decades.

That 30-year plan was authored by Christopher Ruhm, a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Virginia. He says you can easily get into the billions when you consider the costs of dealing with this epidemic in the long term.

“Take one example,” Ruhm says. “Addiction treatment services, which includes a variety of things — that includes inpatient services, outpatient services, residential care. You’re talking a cost there on the order of $230 million per year. And so if you take that over a 30-year period — and then you discount it to net present value and all the things economists do — you come up with a cost for treatment services of just under $6 billion.”

Just that cost gets you more than a third of the way to $17 billion. The rest comes from all sorts of things, he says: public and physician education programs; treatment for babies who are born to mothers who used opioids; data systems for pharmacists to better track prescriptions grief support groups and more. Ruhm added up all those costs over 30 years, and got more than $17 billion.

“Let’s be clear,” he says. “It is a lot of money. It’s also a major public health crisis.” Nationally, 130 people, on average, die every day from opioid-related overdoses, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Ruhm suggests one year of funding for abatement won’t be nearly enough. “Many currently addicted individuals are likely to need medication-assisted treatment for many years, or even for decades. The same is true for many other aspects of the crisis,” he says.

Today’s verdict does not mean Oklahoma is now going to spend the $572 million dollars it was awarded on any particular abatement plan, assuming, even that it sees any of that cash — Johnson & Johnson’s attorneys say they will appeal Monday’s court decision.

Ultimately, it will be up to state officials and lawmakers to decide how to actually use any money the state gets. And that will probably be nowhere near Ruhm’s projection of what’s needed in the long term.

Health economist Kosali Simon at Indiana University says the $17 billion figure didn’t seem outsize to her.

“In general these numbers tend to be large because we’re thinking over a long time period; we’re thinking about a 30-year horizon,” she says. “There isn’t a vaccine or a one-time dose of medication that would completely heal everybody.”

Simon compares Ruhm’s report to what economists did after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 — estimating what it would cost to return the environment as closely as possible to its pre-spill condition.

Except in this case, there isn’t a single oil spill. There is an opioid epidemic in every state.

“This report is going to be a very important and useful baseline against which other states can consider their own situation,” says Simon.

Nationally, she says, it would cost much more than taking Oklahoma’s numbers and scaling them up to solve the problem. The country needs to invest in research on what treatment options work best, develop better addiction treatment drugs, et cetera.

Then there’s the question — once you’ve fully accounted for all these costs — of who should pay?

“The economist’s job is to think, ‘How much money does it take now to abate the setting?’ ” Simon says. “Whose pocket that should come from is an entirely different and — I think — much more difficult question for society to answer.”

Today the judge said a drugmaker should pay at least some of the costs of abating the crisis — at least for one year.

There are hundreds of other opioid cases around the country, and those judges might come to different conclusions.

Academic Science Rethinks All-Too-White ‘Dude Walls’ Of Honor

All the portraits hanging on the wall inside the Louis Bornstein Family Amphitheater at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston on June 12, 2018 were of men, nearly all white. The portraits have since been removed.

Pat Greenhouse/Boston Globe via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Pat Greenhouse/Boston Globe via Getty Images

A few years ago, TV celebrity Rachel Maddow was at Rockefeller University to hand out a prize that’s given each year to a prominent female scientist. As Maddow entered the auditorium, someone overheard her say, “What is up with the dude wall?”

She was referring to a wall covered with portraits of scientists from the university who have won either a Nobel Prize or the Lasker Award, a major medical prize.

“One hundred percent of them are men. It’s probably 30 headshots of 30 men. So it’s imposing,” says Leslie Vosshall, a neurobiologist with the university and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Vosshall says Maddow’s remark, and the word “dude wall,” crystallized something that had been bothering her for years. As she travels around the country to give lectures and attend conferences at scientific institutions, she constantly encounters lobbies, conference rooms, passageways, and lecture halls that are decorated with portraits of white men.

“It just sends the message, every day when you walk by it, that science consists of old white men,” says Vosshall. “I think every institution needs to go out into the hallway and ask, ‘What kind of message are we sending with these oil portraits and dusty old photographs?'”

She’s now on a committee that’s redesigning that wall of portraits at Rockefeller University, to add more diversity. And this is hardly the only science or medical institution that’s reckoning with its dude wall.

At Yale School of Medicine, for example, one main building’s hallways feature 55 portraits: three women and 52 men. They’re all white.

“I don’t necessarily always have a reaction. But then there are times when you’re having a really bad day — someone says something racist to you, or you’re struggling with feeling like you belong in the space — and then you see all those photos and it kind of reinforces whatever you might have been feeling at the time,” says Max Jordan Nguemeni Tiako, a medical student at Yale.

He grew up reading Harry Potter books, and in that fictional world, portraits can talk to the characters. “If this was Harry Potter,” he muses, “if they could speak, what would they even say to me? Everywhere you study, there’s a big portrait somewhere of someone kind of staring you down.”

Yale medical student Nientara Anderson recently teamed up with fellow student Elizabeth Fitzsousa and associate professor Dr. Anna Reisman to study the effect of this artwork; the results were published in July in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

“Students felt like these portraits were not just ancient, historic things that had nothing to do with their contemporary experience,” says Anderson. “They actually felt that the portraits reinforced contemporary issues of exclusion, of racial discrimination — of othering.”

Yale has recently been commissioning new portraits, including one of Carolyn Slayman, a geneticist and member of the Yale faculty for nearly 50 years, as well as one of Dr. Beatrix Hamburg, a pioneering developmental psychiatrist and the first black female Yale medical school graduate. And there’s an ongoing discussion at Yale about what to do with all those old portraits lining the hallways.

One option is to move them someplace else. That was the approach taken at the department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology at the University of Michigan. Ally Cara, a Ph.D. student there, says its seminar room “featured portraits of our past department chairs, which happened to be all male.”

The 10 or so photographs were lined up in a row. “When our interim chair, Dr. Santiago Schnell began his service a couple years ago, he wanted to bring a more modern update to our seminar room,” Cara says, “including bringing down the dude wall and relocating it.”

The photos are now in a less noticeable spot: the department chair’s office suite. And the seminar room will soon be decorated with artwork depicting key discoveries made by the department’s faculty, students, and trainees.

“We really want to emphasize that we’re not trying to erase our history,” says Cara. “We’re proud of the people who have brought us to where we are today as a department. But we also want to show that we have a diverse and inclusive department.”

Changes like this can be a sensitive subject. At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, one of Harvard’s teaching hospitals, there’s an auditorium that for decades was covered with large portraits of 31 men.

“It made an impression,” says Dr. Jeffrey Flier of Harvard Medical School, who first saw the wall of portraits back in the 1970’s. But recently, he walked in the auditorium and “was taken aback because, instead of this room filled with portraits of historically important figures from the Brigham, the walls were empty.”

When I last lectured in ?@BrighamWomens? Bornstein auditorium, walls were adorned with portraits of prior luminaries of medicine & surgery. Connecting to a glorious past. Now all gone. Hope everyone is happy. I’m not. (Neither were those I asked- afraid to say openly). Sad. pic.twitter.com/Bsz89r2SBB

— Jeffrey Flier (@jflier) April 12, 2019

The portraits were relocated to different places around the hospital. And while Flier says he understands why there needed to be a change, he prefers the approach taken in another Harvard meeting place called the Waterhouse Room.

It had long been decorated with paintings of former deans, says Flier, and “all of those individuals were white males. I am among them now, hanging up there as the most recent former dean of Harvard Medical School.”

But right up there with Flier’s portrait are photographs of well-known female and African-American physician-scientists, he says, because his predecessor added them to the walls of that room.

“You don’t want to take away the history of which you are justifiably proud,” says Flier. “You don’t want to make it look like you are embarrassed by that history. Use the space to reflect some of the past history and some of the changing realities that you want to emphasize.”

But some argue that the old portraits themselves have erased history, by glorifying white men who hold power while ignoring the contributions to science and medicine made by women and people of color.

One rare exception, and a poignant example of the power and meaning of portraits in science and medicine, can be found at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. There, a black technician named Vivien Thomas worked for a white surgeon named Alfred Blalock. Even though Thomas had only a high school degree, he joined Blalock’s lab in 1930; the pair spent decades developing pioneering techniques for cardiac surgery together.

The last time the two ever spoke, Blalock was in poor health, and in a wheelchair. Together they went to see the portrait of Blalock that had recently been hung in the lobby of the clinical sciences building, which had been named after him.

Soon after that, Blalock died. And a few years later, Thomas received word that a group of surgeons was commissioning a portrait of him. “My first reaction was that surely I must be dreaming,” Thomas wrote in his autobiography, which he originally entitled Presentation of a Portrait: The Story of a Life.

When the portrait was presented to the hospital in 1971, Thomas told the assembled surgeons that he felt proud and humbled. “People in my category are not accustomed to being in the limelight as most of you are,” Thomas said. “If our names get into the print, it’s usually in the very fine print down at the bottom somewhere.”

In his memoir Thomas wrote, “it had been the most emotional and gratifying experience of my life.” He wondered where the portrait would be hung, and thought someplace like the 12th floor, near the laboratory area, would be appropriate. He was “astounded” when Dr. Russell Nelson, then the hospital president, stated “We’re going to hang your fine portrait with professor Blalock. We think you hung together and you had better continue to hang together.”

Opinion: We Are Risking Health And Life

A sign for Flu Shots at a CVS Pharmacy in Boston.

Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty Images

It’s flu shot season. Signs alerting and urging you to get a flu shot now may be up at your pharmacy or workplace. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends everyone over 6 months old get a flu shot by the end of October, so the vaccine can begin to work before the influenza season begins.

But this week, U.S. Customs and Border Protection said it would not give flu shots to the thousands of migrants now in its detention centers.

“Due to the short-term nature of CBP holding and the complexities of operating vaccination programs,” the agency said in a statement, “neither CBP nor its medical contractors administer vaccinations to those in our custody.”

Dr. Bruce Y. Lee of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health called the department’s edict, “short-term thinking.”

“Holding a number of unvaccinated people in a crowded space could be like maintaining an amusement park for flu viruses,” he wrote for Forbes. He explains that viruses could spread through the congested, often cold, and unsanitary detention camps, and get passed between those people who’ve been detained — weak, tired and dusty — as well as those who work there.

Viruses spread. They cannot be “detained,” like people.

During a particularly brutal flu season two years ago, the CDC estimated about 80,000 people, including 600 children, died across the U.S. after being infected by influenza. Last season’s flu set records for its length — lasting 21 weeks.

On Aug. 1, a group of six physicians from Johns Hopkins and the MassGeneral Hospital for Children wrote a letter to members of Congress in which they said at least three children infected with influenza have died in U.S. custody since December of 2018.

The children were 2, 8 and 16. They were named Wilmer, Felipe and Carlos.

The doctors advised Congress, “During the influenza season, vaccination should be offered to all detainees promptly upon arrival in order to maximize protection for the youngest and most vulnerable detainees.”

This week I read of the government’s determination not to give seasonal flu shots to migrants in detention centers and had to ask: What possible good will this do? Is it worth the risk to health and life? And what does this policy say about America?

Wyoming Wants To Use Medicaid To Reduce Air Ambulance Bills For All Patients

In rugged, rural areas, patients often have little choice about how they’ll get to the hospital in an emergency. “The presence of private equity in the air ambulance industry indicates that investors see profit opportunities,” a 2017 report from the federal Government Accountability Office notes.

pidjoe/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

pidjoe/Getty Images

Wyoming, which is among the reddest of Republican states and a bastion of free enterprise, thinks it may have found a way to end crippling air ambulance bills that sometimes top $100,000 per flight.

The state’s unexpected solution: Undercut the free market, by using Medicaid to treat air ambulances like a public utility.

Costs for such emergency transports have been soaring, with some patients facing massive, unexpected bills as the free-flying air ambulance industry expands with cash from profit-seeking private-equity investors. The issue has come to a head in Wyoming, where rugged terrain and long distances between hospitals forces reliance on these ambulance flights.

Other states have tried to rein in the industry, but have continually run up against the Airline Deregulation Act, a federal law that preempts states from regulating any part of the air industry.

So, Wyoming officials are instead seeking federal approval to funnel all medical air transportation in the state through Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for residents with lower incomes. The state officials plan to submit their proposal in late September to Medicaid’s parent agency, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; the plan will still face significant hurdles there.

If successful, however, the Wyoming approach could be a model for the nation, protecting patients in need of a lifesaving service from being devastated by a life-altering debt.

“The free market has sort of broken down. It’s not really working effectively to balance cost against access,” says Franz Fuchs, a policy analyst for the Wyoming Department of Health. “Patients and consumers really can’t make informed decisions and vote with their dollars on price and quality.”

Freewheeling free market system

The air ambulance industry has grown steadily in the U.S., from about 1,100 aircraft in 2007 to more than 1,400 in 2018. During that same time, the fleet in Wyoming has grown from three aircraft to 14. State officials say an oversupply of helicopters and planes is driving up prices, because air bases have high fixed overhead costs. Fuchs says companies must pay for aircraft, staffing and technology, such as night-vision goggles and flight simulators — incurring 85% of their total costs before they fly a single patient.

But with the supply of aircraft outpacing demand, each air ambulance is flying fewer patients. Nationally, air ambulances have gone from an average of 688 flights per aircraft in 1990, as reported by Bloomberg, to 352 in 2016. So, companies have raised their prices to cover their fixed costs and to seek healthy returns for their investors.

A 2017 report from the federal Government Accountability Office notes that the three largest air ambulance operators are for-profit companies with a growing private equity investment. “The presence of private equity in the air ambulance industry indicates that investors see profit opportunities in the industry,” the report says.

While precise data on air ambulance costs is sparse, a 2017 industry report says air ambulance companies spend an average of $11,000 per flight. In Wyoming, Medicare pays an average of $6,000 per flight, and Medicaid pays even less. So air ambulance companies shift the remaining costs — and then some — to patients who have private insurance or are paying out-of-pocket.

As that cost-shifting increases, insurers and air ambulance companies haven’t been able to agree on in-network rates. So the services are left out of insurance plans.

When a consumer needs a flight, it’s billed as an out-of-network service. Air ambulance companies then can charge whatever they want. If the insurer pays part of the bill, the air ambulance company can still bill the patient for the rest — a practice known as balance billing.

“We have a system that allows providers to set their own prices,” says Dr. Kevin Schulman, a Stanford University professor of medicine and economics. “In a world where there are no price constraints, there’s no reason to limit capacity, and that’s exactly what we’re seeing.”

Nationally, the average helicopter bill has now reached $40,000, according to a 2019 GAO report — more than twice what it was in 2010. State officials say Wyoming patients have received bills as high as $130,000.

Because consumers don’t know what an air ambulance flight will cost them — and because their medical condition may be an emergency — they can’t choose to go with a lower-cost alternative, either another air ambulance company or a ground ambulance.

A different way of doing things

Wyoming officials propose to reduce the number of air ambulance bases and strategically locate them, to even out access. The state would then seek bids from air ambulance companies to operate those bases at a fixed yearly cost. It’s a regulated monopoly approach, similar to the way public utilities are run.

“You don’t have local privatized fire departments springing up and putting out fires and billing people,” Fuchs says. “The town plans for a few fire stations, decides where they should be strategically, and they pay for that fire coverage capacity.”

Medicaid would cover all the air ambulance flights in Wyoming — and then recoup those costs by billing patients’ insurance plans for those flights. A patient’s out-of-pocket costs would be capped at 2% of the person’s income or $5,000, whichever is less, so patients could easily figure out how much they would owe. Officials estimate they could lower private insurers’ average cost per flight from $36,000 to $22,000 under their plan.

State Rep. Eric Barlow, who co-sponsored the legislation, recognizes the irony of a GOP-controlled, right-leaning legislature taking steps to circumvent market forces. But the Republican said that sometimes government needs to make sure its citizens are not being abused.

“There were certainly some folks with reservations,” he says. “But folks were also hearing from their constituents about these incredible bills.”

Industry pushback

Air ambulance companies have opposed the plan. They say the surprise-billing problem could be eliminated if Medicare and Medicaid covered the cost of flights and the companies wouldn’t have to shift costs to other patients. They question whether the state truly has an oversupply of aircraft and warn that reducing the number of bases would increase response times and cut access to the lifesaving service.

Richard Mincer, an attorney who represents the for-profit Air Medical Group Holdings in Wyoming, says that while 4,000 patients are flown by air ambulance each year in the state, it’s not clear how many more people have needed flights when no aircraft was available.

“How many of these 4,000 people a year are you willing to tell, ‘Sorry, we decided as a legislature you’re going to have to take ground ambulance?’ ” Mincer said during a June hearing on the proposal.

But Wyoming officials say it indeed might be more appropriate for some patients to take ground ambulances. The vast majority of air ambulance flights in the state, they say, are transfers from one hospital to another, rather than on-scene trauma responses. The officials say they’ve also heard of patients being flown for medical events that aren’t an emergency, such as a broken wrist or impending gallbladder surgery.

Air ambulance providers say such decisions are out of their control: They fly when a doctor or a first responder calls.

But air ambulance companies do have ways of drumming up business: They heavily market memberships that cover a patient’s out-of-pocket costs, eliminating any disincentive for the patient to fly. Companies also build relationships with doctors and hospitals that can influence the decision to fly a patient; some have been known to deliver pizzas to hospitals by helicopter to introduce themselves.

Mincer, the Air Medical Group Holdings attorney, says the headline-grabbing, large air ambulance bills don’t reflect what patients end up paying directly. The average out-of-pocket cost for an air ambulance flight, he says, is about $300.

The industry also has tried to shift blame onto insurance plans, which the transporters say refuse to pay their fair share for air ambulance flights and refuse to negotiate lower rates.

Doug Flanders, director of communications and government affairs for the medical transport company Air Methods, says the Wyoming plan “does nothing to compel Wyoming’s health insurers to include emergency air medical services as part of their in-network coverage.”

The profit model

Other critics of the status quo maintain that air ambulance companies don’t want to change, because the industry has seen investments from Wall Street hedge funds that rely on the balance-billing business model to maximize profits.

“It’s the same people who have bought out all the emergency room practices, who’ve bought out all the anesthesiology practices,” says James Gelfand, senior vice president of health policy for the ERISA Industry Committee, a trade group representing large employers. “They have a business strategy of finding medical providers who have all the leverage, taking them out of network and essentially putting a gun to the patient’s head.”

The Association of Air Medical Services counters that the industry is not as lucrative as it’s made out to be, pointing to the recent bankruptcy of PHI Inc., the nation’s third-largest air ambulance provider.

Meanwhile, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Wyoming is supportive of the state’s proposal and looks forward to further discussion about the details if approved, according to Wendy Curran, a vice president at the health insurance firm. “We are on record,” Curran says, “as supporting any effort at the state level to address the tremendous financial impacts to our [Wyoming] members when air ambulance service is provided by an out-of-network provider.”

The Wyoming proposal also has been well received by employers, who like the ability to buy into the program at a fixed cost for their employees, providing a predictable annual cost for air ambulance services.

“It is one of the first times we’ve … seen a proposal where the cost of health care might actually go down,” says Anne Ladd, CEO of the Wyoming Business Coalition on Health.

The real challenge, Fuchs says, will be convincing federal officials to go along with it.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Tales Of Corporate Painkiller Pushing: ‘The Death Rates Just Soared’

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that most new heroin addicts first became hooked on prescription painkillers, such as oxycodone, before graduating to heroin, which is cheaper.

John Moore/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

John Moore/Getty Images

Nearly 2,000 cities, towns and counties across America are currently participating in a massive multidistrict civil lawsuit against the opioid industry for damages related to the abuse of prescription pain medication. The defendants in the suit include drug manufacturers like Mallinckrodt, wholesale distributors McKesson and Cardinal Health, and pharmacy chains CVS and Walgreens.

Evidence related to the lawsuit was initially sealed, but The Washington Post and the Charleston Gazette-Mail successfully sued to have it made public. Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post journalist Scott Higham says the evidence, which was released in July, includes sworn depositions and internal corporate emails that indicate the drug industry purposely shipped suspiciously large quantities of drugs without regard for how they were being used.

Higham says one sales director at the pharmaceutical manufacturer Mallinckrodt was jokingly called “ship, ship, ship” by colleagues because of the amount of oxycodone and hydrocodone he sold: “His bonus structure was tied to the amount of sales that he made,” Higham notes. “And that was a time when there was no secret about how many people were dying in places across the country, and the opioid epidemic was raging.”

Higham and his colleagues at the Post were also able to access data from the Drug Enforcement Agency that trace the path of some 76 billion opioid pain pills sold between 2006 and 2012. In analyzing the movement of those pills, they made a gruesome discovery.

“When you line up the CDC death [by overdose] database with the DEA’s database on opioid distribution, you see a clear correlation between the saturation of towns and cities and counties and the numbers of deaths,” Higham says. “A lot of these towns and cities, small cities and counties in places like Ohio and Pennsylvania have just been devastated. … The death rates just soared in those places where the pills were being dumped.”

Interview Highlights

On the picture emerging from recently unsealed DEA database

A lot of people thought they knew that their communities were being saturated by these opioids, but I don’t think they really knew the extent of the saturation, and who was responsible. So this database pulls the curtain back on that for the first time. We obtained data that goes from 2006 through 2012. So over that seven-year period … you can see exactly which manufacturers were responsible, which distributors were responsible, and which pharmacies were responsible. And we took that database and we turned it into a usable, public-facing database, so now anybody in the country can go onto our website and they can see exactly what happened in their communities. …

Dozens and dozens of local news organizations have done stories about their own communities — which companies flooded their communities with pills, which pharmacies were responsible for dispensing the most tablets of oxycodone and hydrocodone. Those are the two drugs that we looked at, because they are the most widely abused drugs by addicts and by drug dealers.

On the communities that were flooded with opioids

It’s just heartbreaking to see these once thriving communities. They’re almost like zombielands, where people are just walking around in a daze and picking through garbage cans and falling down, and overdosing in public parks and inside of cars and inside of streets and on street corners. It’s a very upsetting scene that’s happening. …

These communities need help — desperately need help. Their hospitals need help. Their foster care agencies need help — because so many parents have perished and their kids have no family or [are] being raised by grandparents. Police departments, paramedics, fire departments that used to fight fires all the time now are fighting against the opioid epidemic and carrying Narcan with them, which is an overdose reversal drug, and “Narcaning” people all day long.

On how drug distributors generated billions in revenue from the opioid epidemic

They’re making massive amounts of money. Many of them are Fortune 500 companies. In fact, the No. 1 drug distributor in America, McKesson Corp., is the fifth-largest company in the United States — fifth-largest of all companies in the United States — and it’s a company that most people have never heard of. And they are a huge, huge player in this world, and of the distributors that sent these drugs downstream they were No. 1. And they were followed by two other companies that a lot of folks probably have not heard of. One is called AmerisourceBergen and another is called Cardinal Health. … Together those three companies are the three biggest drug distributors in the United States. And they were followed by Walgreens, CVS and Walmart as the top six drug distributors in the United States.

On “pill mills” that popped up in Florida, where people could get opioids from corrupt doctors — and then resell them on the street

All of a sudden, all these drug dealers realize that there was another way to peddle these pills, and they began to open up these so-called pain management clinics, and most of them were in South Florida, heavily concentrated in Broward County, which is where Fort Lauderdale is. … These things … were basically storefront operations in strip malls where you had corrupt doctors and rogue pharmacists working hand in hand inside of a store. So on one side of the store you’d come in, you’d get a cursory examination, the doctor would write you a script. And you literally go next door and get it filled. And these places just became huge open-air drug markets. The parking lots were filled with people who were driving down from Kentucky and West Virginia and Ohio to pick up their prescriptions. And along the highway that goes up through Florida, I-75 and then also I-95, a lot of these storefronts began putting up billboards along the highway at exit ramps saying, “Pain management clinic, next exit.”

On the Justice Department’s history of fining drug companies instead of filing criminal charges

[Investigators at the DEA’s Office of Diversion Control] started to see a pattern, and it’s a pattern that they see that continues to this day, that there are people within the Justice Department who are not very aggressive when it comes to these cases. They feel that some of them are a little too close to the industry; that maybe some of the people in the Justice Department want to work for the industry one day, so they don’t go as hard against these companies as perhaps they should. … If you take a look at the revolving door between the Justice Department, the DEA and the drug industry, it’s a very impressive revolving door. You have dozens and dozens of high-ranking officials from the DEA and from the Justice Department who have crossed over to the other side and they’re now working directly for the industry or for law firms representing the industry. So if you’re a DEA investigator or a DEA lawyer or a Justice Department lawyer making $150,000 a year, you cross over and you can triple, quadruple your salary overnight.

Amy Salit and Seth Kelley produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz and Deborah Franklin adapted it for the Web.

Poll: Nearly 1 in 5 Americans Says Pain Often Interferes With Daily Life

According to the latest NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll exercise, including stretching and yoga, is popular among younger people as a way to relieve pain.

Daniel Grill/Getty Images/Tetra images RF

hide caption

toggle caption

Daniel Grill/Getty Images/Tetra images RF

At some point nearly everyone has to deal with pain.

How do Americans experience and cope with pain that makes everyday life harder? We asked in the latest NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll.

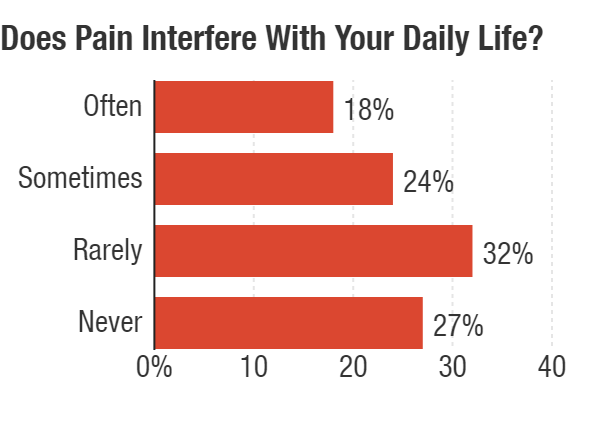

First, we wanted to know how often pain interferes with people’s ability to work, go to school or engage in other activities. Overall, 18% of Americans say that’s often a problem for them. Almost a quarter – 24% — say it’s sometimes the case.

(Note: Because of rounding, total exceeds 100%)

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

The degree to which pain is a problem varies by age, with 22% of people 65 and older saying pain interferes often with their daily lives compared with only about 9% of people 35 and younger.

Once pain strikes, how do people deal with it?

The poll found that 63% of people had sought care for their pain and 37% hadn’t. Younger people were less likely to have pursued care.

The most common approach is an over-the-counter pain reliever. Sixty percent of people said that is something they do. Another popular choice, particularly among younger people, is exercise, including stretching and yoga. Forty percent of those under 35 say exercise is a way they seek relief. Only 11% of people 65 and older say exercise is something they try for pain. Overall, 26% of people see exercise as helpful for their pain.

That level of exercise is “really exciting to see,” says Brett Snodgrass, a nurse practitioner and clinical coordinator of palliative medicine at Baptist Hospitals in Memphis, Tenn. In her experience, not nearly as many people were doing that, even a few years ago.

She says a decline in opioid prescribing could be part of the reason for the change. “Often prescribers were settling for prescriptions,” she says of health care providers’ longstanding approach. “Now that there’s less prescribing, patients are having to take more responsibility” for managing their pain, she says.

But options such as exercise and physical therapy are easier to access for people with higher incomes. Snodgrass points to the poll’s finding that only 15% of people whose income was less than $25,000 a year cite exercise as a way they relieve pain. By comparison, about a third of people making $50,000 or more annually say it’s one way they deal with it.

(Note: Up to two choices were allowed.)

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR-IBM Watson Health Poll

About 15% of Americans do turn to a prescription medicine to help get relief. People 35 and under were least likely to get a prescription drug for pain – only 3%. Older people, those 65 and older, were most likely to make use of a prescription medicine, with 23% opting for that approach.

In terms of treatment, pain needs to be viewed holistically, so that reliance on medicines alone doesn’t drive decisions. “If we don’t pay attention to pain as a public health issue, I think we’re going to be addressing half of the problem and causing another problem,” says Dr. Anil Jain, vice president and chief health information officer at IBM Watson Health.

In light of the efforts to reduce opioid use, we asked if people who are taking opioids for pain are concerned about becoming addicted: 16% said yes; 84% said no.

A little more than a third of people taking opioids said they were worried about losing access to opioids compared with about two-thirds who aren’t.

The nationwide poll surveyed 3,004 people during the first half of March. The margin of error is +/- 1.8 percentage points.

You can find the full results here.

Former Arkansas VA Doctor Charged With Involuntary Manslaughter In 3 Deaths

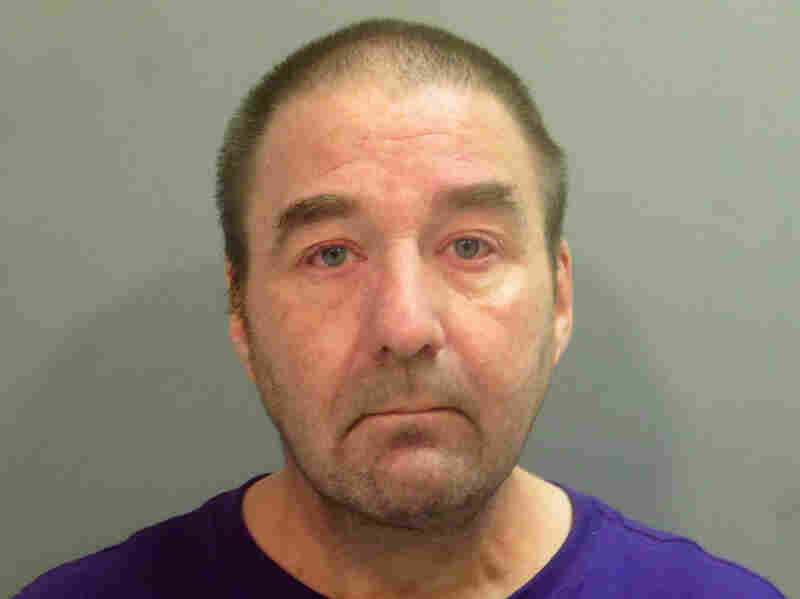

Pathologist Robert Levy was fired from an Arkansas veterans hospital after officials said he had been impaired while on duty.

AP

hide caption

toggle caption

AP

A former pathologist at an Arkansas veterans hospital was charged with three counts of involuntary manslaughter in the deaths of three patients whose records he allegedly falsified to conceal his misdiagnoses.

According to federal prosecutors, Dr. Robert Morris Levy, 53, is also charged with four counts of making false statements, 12 counts of wire fraud and 12 counts of mail fraud, stemming from his efforts to conceal his substance abuse while working at the Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks.

Levy was suspended from work twice — in March 2016 and again in October 2017 — for working while impaired, before he was fired in April 2018.

A June 2018 review of his work examined 33,902 cases and found more than 3,000 mistakes or misdiagnoses of patients at the veterans hospital dating to 2005. Thirty misdiagnoses were found to have resulted in serious health risks to patients.

The three deaths came as a result of incorrect or misleading diagnoses. In one case, according to prosecutors, a patient died of prostate cancer after Levy concluded that a biopsy indicated that he didn’t have cancer.

“This indictment should remind us all that this country has a responsibility to care for those who have served us honorably,” Duane Kees, the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Arkansas, said in a statement. “When that trust is violated through criminal conduct, those responsible must be held accountable. Our veterans deserve nothing less.”

Kees said Levy went to great lengths to conceal his substance abuse even during a period when he had pledged to maintain his sobriety.

Levy used 2-Methyl-2-butanol, a chemical substance that intoxicates a person “but is not detectable in routine drug and alcohol testing methodology,” the statement said.

Planned Parenthood May Reject Federal Funds Over Changes To Title X

It appears some health care providers that offer birth control, such as Planned Parenthood, are going to withdraw from the federal Title X program. Changes to Title X take effect Monday.

NOEL KING, HOST:

About 4 million low-income Americans get birth control and other kinds of reproductive health care through a federal program called Title X. The Trump administration is making some changes to that program, and they’re set to take effect today. Because of those changes, Planned Parenthood and some other providers say they’re going to withdraw from Title X. NPR correspondent Sarah McCammon covers reproductive rights. She’s with me now. Hi, Sarah.

SARAH MCCAMMON, BYLINE: Good morning.

KING: So a lot at stake here, apparently. What exactly is changing with Title X today?

MCCAMMON: Well, today is a key deadline that the Trump administration has set for recipients of these Title X funds to confirm that they’re making a good faith effort to comply with new rules set by the administration for the program. And that means it’s likely that a substantial number of health care providers around the country that provide these services, most notably Planned Parenthood clinics, are going to withdraw from the Title X program by the end of the day, at least that’s the way it appears.

This is a big program, Noel. It’s $286 million each year. It covers contraceptive services, STD screenings – things like that. And under these new rules, any organization that provides abortions or advises patients on how to get them – except in a few cases like rape, incest and medical emergencies – will not be able to get these funds to provide other services.

KING: OK, so Planned Parenthood is a huge organization. It is used – its services are used by a lot of women. It’s refusing to comply with these rules. Why?

MCCAMMON: Right. Well, they call the rule a gag rule. I spoke with Planned Parenthood’s acting president, Alexis McGill Johnson, and she said it interferes with the doctor-patient relationship.

ALEXIS MCGILL JOHNSON: Imagine if you show up as a patient to a health center and the doctor’s only ability is to refer you to prenatal care, and you may have already decided that you would like to have an abortion, federal regulations will ban that doctor from actually giving you the advice and referring you to abortion.

MCCAMMON: And Planned Parenthood made a last-ditch plea last week to a federal appeals court asking them to block the rule. That request was turned down on Friday. And Planned Parenthood had said this will effectively force them out of Title X, which is a pretty big deal because the organization has been a major part of the program for decades, and they say they serve about 40% of those 4 million people nationwide who get those services through this program.

And while it’s not just Planned Parenthood, for example, Maine Family Planning and some other organizations are also pulling out.

KING: Just quickly – what is the Trump administration saying in response to these groups saying, we’re just not going to be a part of this?

MCCAMMON: Well, they say that all providers of reproductive health care through this program just have to comply with the rule – either stop performing abortions or referring patients for them, and they can stay in. In a statement, the administration said that Planned Parenthood is, quote, “actually choosing to place a higher priority on the ability to refer for abortion instead of continuing to receive federal funds.”

The rule is a big victory, too, for opponents of abortion rights, who’ve pushed for a long time to cut public dollars to Planned Parenthood. I talked to a spokeswoman for the anti-abortion group the SBA List this weekend. She said Planned Parenthood is demonstrating, quote, “how committed they are to performing abortion.”

KING: But what does this mean for all of those low-income patients who use Title X?

MCCAMMON: It’s not entirely clear what happens next. Planned Parenthood and Maine Family Planning, for example, had stopped using these funds already a few weeks ago and were patching through with other types of funding. But I’m told that cannot continue indefinitely, so some services may be scaled back or cut. Patients may have to pay more for things like birth control.

And the groups that support this rule, though, are pointing out that there are thousands of other organizations, like community health centers, that don’t offer abortions that also get these funds. But a lot of patients go to Planned Parenthood and similar groups, and they’re used to going there for this kind of care, so this does represent a big shift. We’re also expecting to hear more from Planned Parenthood today about their legal strategy and how they plan to move forward now that this rule is taking effect.

KING: All right, we’ll keep an eye on that. NPR correspondent Sarah McCammon. Thanks, Sarah.

MCCAMMON: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

No Mercy: After The Hospital Closes, How Do People Get Emergency Care?

Mercy Hospital Fort Scott closed in December, leaving Fort Scott Kan., without its longtime provider of emergency medical services.

Sarah Jane Tribble for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Sarah Jane Tribble for Kaiser Health News

For more than 30 minutes on a frigid February morning, Robert Findley lay unconscious in the back of an ambulance as paramedics hand-pumped oxygen into his lungs.

They were waiting for a helicopter to land at a helipad just across the icy parking lot next to Mercy Hospital Fort Scott, which closed in December. The night before, Findley had fallen on the slick driveway outside his home while checking the mail. He had laughed it off, ate dinner and went to bed.

In the morning, he wouldn’t wake up. Linda, his wife, called 911.

When the Fort Scott, Kan., paramedics arrived, they suspected he had an intracerebral hemorrhage. Robert Findley needed specialized neurological care and the closest available center was located 90 miles north in Kansas City, Mo.

After rural hospitals like the one in Fort Scott close, one of the thorniest dilemmas communities face is how to provide emergency care, particularly for patients who require specialized expertise. In times of crisis, the local emergency workers can find themselves dealing with changing leadership, budgets and questions about where to take patients. Air ambulance companies are often seen as a key part of the solution.

The dispatcher for Air Methods, a private air ambulance company, checked with at least four bases before finding a pilot to accept the flight for Robert Findley, according to a 911 tape obtained by Kaiser Health News through a Kansas Open Records Act request.

Linda Findley’s husband, Robert, opened Findley Body Repair in 1975. Linda says she doesn’t know what she’s going to do with the Fort Scott, Kan., business. She kept two workers on for six weeks after Robert’s death to close out active orders. “I guess I’ll have to have an auction someday,” Findley says.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

“My Nevada crew is not available and my Parsons crew has declined,” the operator tells Fort Scott’s emergency line about a minute after taking the call. Then she says she will be “reaching out to” another crew.

Nearly seven minutes passed before one was en route.

When Linda Findley sat at her kitchen counter in late May and listened to the 911 tape, she blinked hard: “I didn’t know that they could just refuse. … I don’t know what to say about that.”

Both Mercy and Air Methods declined to comment on the case.

When Mercy Hospital Fort Scott closed at the end of 2018, hospital president Reta Baker had been “absolutely terrified” about the possibility of not having emergency care for a community where she had raised her children and grandchildren and served as chair of the local Chamber of Commerce.

Now, just a week after the ER’s closure, her fears were being tested.

Nationwide, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, and in each instance a community struggles to survive in its own way. In Fort Scott, home to 7,800, the loss of its 132-year-old hospital opened by nuns in the 19th century has wrought profound social, emotional and medical consequences. Kaiser Health News and NPR are following Fort Scott for a year to explore deeper national questions about whether small communities need a traditional hospital at all. If not, what would take its place?

A delay in emergency care can make the difference between life and death. Seconds can be crucial when it comes to surviving a heart attack, a stroke, an anaphylactic allergic reaction or a complicated birth.

Though air ambulances can transport patients quickly, the dispatch system is not coordinated in many states and regions across the country. And many air ambulance companies do not participate in insurance networks, which leads to bills of tens of thousands of dollars.

Knowing that emergency care was crucial, the hospital’s owner, St. Louis-based Mercy, agreed to keep Fort Scott’s emergency doors open an extra month past the hospital’s Dec. 31 closure, to give Baker time to find a temporary operator. A last-minute deal was struck with a hospital about 30 miles away to take it over, but the ER still needed to be remodeled and the new operator had to meet regulatory requirements. So, the ER closed for 18 days — a period that proved perilous.

A risky experiment

During that time, Fort Scott’s publicly funded ambulances responded to more than 80 calls for service and drove more than 1,300 miles for patients to get care in other communities.

Across America, rural patients spend more time in an ambulance than urban patients after a hospital closes, said Alison Davis, a professor at the University of Kentucky’ department of agriculture economics. Davis and research associate SuZanne Troske analyzed thousands of ambulance calls and found the average transport time for a rural patient was 14.2 minutes before a hospital closed; afterward, it increased nearly 77% to 25.1 minutes. For patients over 64, the increase was steeper, nearly doubling.

In Fort Scott this February, the hospital’s closure meant people didn’t “know what to expect if we come pick them up,” or where they might end up, said Fort Scott paramedic Chris Rosenblad.

During 18-day gap in ER services, Barbara Woodward slipped on ice outside a downtown Fort Scott business. She was driven 30 miles out of town of care. “I thought to myself that the back of the ambulance isn’t as comfortable as I thought it would be,” Woodward says.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

Barbara Woodward, 70, slipped on ice outside a downtown Fort Scott business during the early February storm. The former X-ray technician said she knew something was broken. That meant a “bumpy” and painful 30-mile drive to a nearby town, where she had emergency surgery for a shattered femur, a bone in her thigh.

About 60% of calls to the Fort Scott’s ambulances in early February were transported out of town, according to the log, which KHN requested through the Kansas Open Records Act. The calls include a 41-year-old with chest pain who was taken more than 30 miles to Pittsburg, an unconscious 11-year-old driven 20 miles to Nevada, Mo., and a 19-year-old with a seizure and bleeding eyes escorted nearly 30 miles to Girard, Kan.

Traveling those distances can harm patients’ health when they are experiencing a traumatic event, Davis said. They also prompt other, less obvious, problems for a community. The travel time keeps the crews absent and unable to serve local needs. Plus, those miles cause expensive emergency vehicles to wear out faster.

Mercy donated its ambulances to the joint city and county emergency operations department. Bourbon County Commissioner Lynne Oharah said he’s not sure how they will pay for upkeep and the buying of future vehicles. Mercy had previously owned and maintained the fleet, but now it falls to the taxpayers to support the crew and ambulances. “This was dropped on us,” said LeRoy “Nick” Ruhl, also a county commissioner.

Barbara Woodward’s bumpy ride was just the beginning of a difficult journey. She had shattered her femur and had trouble healing after an emergency surgery. In May, Woodward had a full hip replacement in Kansas City, Kan.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

Even local law enforcement feel extra pressure when an ER closes down, said Bourbon County Sheriff Bill Martin. Suspects who overdose or suffer split lips and black eyes after a fight need medical attention before getting locked up — that often forces officers to escort them to another community for emergency treatment.

And Bourbon County, with its 14,600 residents, faces the same dwindling tax base as most of rural America. According to the U.S. Census, about 3.4% fewer people live in the county compared with nearly a decade ago. Before the hospital closed, Bourbon County paid Mercy $316,000 annually for emergency medical services. In April, commissioners approved an annual $1 million budget item to oversee ambulances and staffing, which the city of Fort Scott agreed to operate.

In order to make up the nearly $700,000 difference in the budget, Oharah said the county is counting on the ambulances to transport patients to hospitals. The transports are essential because ambulance services get better reimbursement from Medicare and private insurers when they take patients to a hospital as compared to when they treat patients at home or at an accident scene.

Added response times

For time-sensitive emergencies, Fort Scott’s 911 dispatch calls go to Air Methods, one of the largest for-profit air ambulance providers in the U.S. It has a base 20 miles away in Nevada, Mo., and another base in Parsons, Kan., about 60 miles away.

The company’s central communications hub, known as AirCom, in Omaha, Neb., gathers initial details of an incident before contacting the pilot at the nearest base to confirm response, said Megan Smith, a spokeswoman for the company. The entire process happens in less than five minutes, Smith said in an emailed statement.

When asked how quickly the helicopter arrived for Robert Findley, Bourbon County EMS Director Robert Leisure said he was “unsure of the time the crew waited at the pad.” But, he added, “the wait time was very minimal.”

Rural communities nationwide are increasingly dependent on air ambulances as local hospitals close, said Rick Sherlock, president of the Association of Air Medical Services, an industry group that represents the air ambulance industry. AAMS estimates that nearly 85 million Americans rely on the mostly hospital-based and private industry to reach a high-level trauma center within 60 minutes, or what the industry calls the “golden hour.”

In June, when Sherlock testified to Congress about high-priced air ambulance billing, he pointed to Fort Scott as a devastated rural community where air service “helped fill the gap in rural health care.”

But, as Robert Findley’s case shows, the gap is often difficult to fill. After Air Methods’ two bases failed to accept the flight, the AirCom operator called at least two more before finding a ride for the patient. Air ambulances can be delayed because of bad weather or crew fatigue from previous runs.

The 1978 Airline Deregulation Act states that airline companies cannot be regulated on “rates, routes, or services,” a provision originally meant to ensure that commercial flights could move efficiently between states. Today, in practice, that means air ambulances have no mandated response times, there are no requirements that the closest aircraft will come, and they aren’t legally obligated to say why a flight was declined.

The air ambulance industry has faced years of scrutiny over accidents, including investigations by the National Transportation Safety Board and stricter rules from the Federal Aviation Administration. And Air Methods’ Smith said the company does not publicly report on why flights are turned down

because “we don’t want pilots to feel pressured to fly in unsafe conditions.”

Yet, a lack of accountability can lead the mostly for-profit providers to sometimes putting profits first, Scott Winston, Virginia’s assistant director of emergency medical services, wrote in an email. Sometimes companies accept a call knowing their closest aircraft is unavailable, rather than lose the business. “This could result in added response time,” he wrote.

Air ambulances don’t face the detailed reporting requirements imposed on ground ambulances. The National Emergency Medical Services Information System collects only about 50% of air ambulance events because the industry’s private operators voluntarily provide the information.

Ascension Via Christi’s Pittsburg, Kan., hospital took over responsibility for ER services in Fort Scott, Kan., after that town’s only hospital closed.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

Saving lives

It took months, but Baker persuaded Ascension Via Christi’s Pittsburg hospital, to reopen the ER. “They kind of were at a point of desperation,” said Randy Cason, president of Pittsburg’s hospital. The two Catholic health systems signed a two-year agreement, leaving Fort Scott relieved but nervous about the long term.

Ascension has said it is looking at potential facilities in the area, but it’s unclear what that means. Fort Scott Economic Development Director Rachel Pruitt said in a July 23 email, “No decisions have been made.” Fort Scott City Manager Dave Martin said the city has entered into a “nondisclosure agreement” with Ascension. Nancy Dickey, executive director of the Texas A&M Rural & Community Health Institute, said every community prioritizes emergency services. That’s because the “first hour appears to be vitally important in terms of outcomes,” she said.

And the Fort Scott ER, which reopened under Ascension on Feb. 18, has proved its value. In the past six months, the Fort Scott emergency department has taken care of more than 2,500 patients, including delivering three babies. In May, a city ambulance crew resuscitated a heart attack patient at his home and Ascension’s emergency department staff treated the patient until an air ambulance arrived.

In July, Fort Scott’s Deputy Fire Chief Dave Bruner read a note from that patient’s grateful wife at a city commission meeting: “They gave my husband the chance to fight long enough to get to Freeman ICU. As a nurse, I know the odds of Kevin surviving the ‘widow-maker’ were very poor. You all made the difference.”

Robert Findley died after falling on the ice during a winter storm this February in Fort Scott, Kan. Mercy Hospital had recently closed, so he had to be flown to a neurology center 90 miles north in Kansas City, Mo.

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Smith for Kaiser Health News

By contrast, Linda Findley believes the local paramedics did everything possible to save her husband but wonders how the lack of an ER and the air ambulance delays might have affected her husband’s outcome. After being flown to Kansas City, Robert Findley died.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Creative Recruiting Helps Rural Hospitals Overcome Doctor Shortages

The wide-open spaces of Arco, Idaho, appeal to some doctors with a love of the outdoors.

Thomas Hawk/Flickr

hide caption

toggle caption

In the central Idaho community of Arco, where Lost Rivers Medical Center is located, the elk and bear outnumber the human population of a thousand. The view from the hospital is flat grassland surrounded by mountain ranges that make for formidable driving in wintertime.

“We’re actually considered a frontier area, which I didn’t even know was a census designation until I moved there,” says Brad Huerta, CEO of the hospital. “I didn’t think there’s anything more rural than rural.”

There are no stoplights in the area. Nor is there a Costco, a Starbucks or — more critically — a surgeon. With 63 full-time employees, the hospital is the county’s largest employer, serving an area larger than Rhode Island.

Six years ago, the hospital declared bankruptcy and was on the cusp of closing. Like many other rural hospitals, it was beset by challenges, including chronic difficulties recruiting medical staff willing to live and work in remote, sparsely populated communities. A hot job market made that even harder.

But against the odds, Huerta has turned Lost Rivers around. He trimmed budgets, but also invested in new technologies and services. And he focused on recruitment.

Kearny County Hospital CEO Benjamin Anderson, left, and Bradley Huerta, CEO of Lost Rivers Medical Center.

Courtesy of Becky Chappel and Bradley Huerta

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Becky Chappel and Bradley Huerta

He targeted older physicians — semiretired empty nesters willing to work part time. He also lured recruits using the area’s best asset: the great outdoors.

“You like mountain climbing, we’re gonna go mountain climbing,” says Huerta, who also uses his local connections to take recruits and their families on ATV tours or flights on small planes, if they’re interested. “The big joke in health care is you don’t recruit the person you recruit their spouse.”

Huerta’s approach has paid off; Lost Rivers is now fully staffed.

Recruitment is a life or death issue, not just for patients in those areas, but for the hospitals themselves, says Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association. Over the last decade, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed, he says, and over the next decade, another 700 more are at risk.

“Keeping access to health care in rural America is simply a challenge no matter how you look at it, but this shortage of rural health care professionals just is an unfortunate driving issue towards more closures,” Morgan says.

And that’s affecting the health of rural communities. “Most certainly the workforce shortages in rural America are contributing towards the decreased life expectancy that we’re seeing in rural America,” he says.

For some rural hospitals, that dire need is the basis of their recruiting pitch: Come here. Make a difference.

That is the crux of Benjamin Anderson’s approach at Kearny County Hospital in the southwestern Kansas town of Lakin.

With a population of about 2,000, last year The Washington Post ranked Lakin one of the country’s most “middle of nowhere” places.

Anderson says he’s found success targeting people motivated by mission over money: “A person that is driven toward the relief of human suffering and the pursuit of justice and equity.”

It’s not that the hospital ignores practical concerns. Hospital staff often house-hunt for recruits, or manage home renovations for incoming workers. Anderson, who isn’t a doctor, also personally babysits the children of his staff, because Lakin lacks nanny services.

“I mean as a CEO I do a lot of different things, but that’s among the most important, because it communicates we love you,” Anderson says. “We’re gonna live in a remote area but we’re gonna live here and support each other.”

But the cornerstone of the hospital’s recruitment pitch is 10 weeks of paid sabbatical a year, which allows time for doctors to serve on medical missions overseas.

Anderson says he came to appreciate the draw of that after a mentor told him, “Go with them and see what motivates them; see why they would want to go there.” Anderson did. It not only changed his life, he says, “I realized that in rural Kansas we have more in common with rural Zimbabwe than we do with Boston, Mass.”

It’s a compelling enough draw that every couple of weeks, Anderson gets a call from physicians saying they want to work in Lakin, despite its remoteness.

One of those callers was Dr. Daniel Linville. He’d read about Kearny County Hospital and its sabbaticals in a magazine article during medical school. Last fall, Linville joined the hospital, having done mission work since childhood in Ecuador, Kenya and Belize.

He says he and his physician wife were also drawn to the surprisingly diverse population Kearny County Hospital serves, including immigrants from Somalia, Vietnam, Laos and Guatemala. In that sense, says Linville, every day feels like an international medical mission, requiring everything from delivering babies to treating dementia.

But life in Lakin also been an adjustment.

“Now that we’ve been out here practicing for a little bit, we realize exactly how rural we are,” Linville says. It’s not just that same-day shipping takes four days; transferring a patient to the next biggest hospital in Wichita means the ambulance and staff are gone for an 8-hour round-trip ride.

And, in an incredibly tight-knit community where he is a newcomer, he’s often reminded that patients see him as another doctor just passing through.

“We’re seen a little bit as outsiders,” Linville says. “We get asked frequently: ‘How long are you here for?’ “

I don’t know, he tells them. But for now, I’m happy.