How A Prenatal ‘Bootcamp’ For New Dads Helps The Whole Family

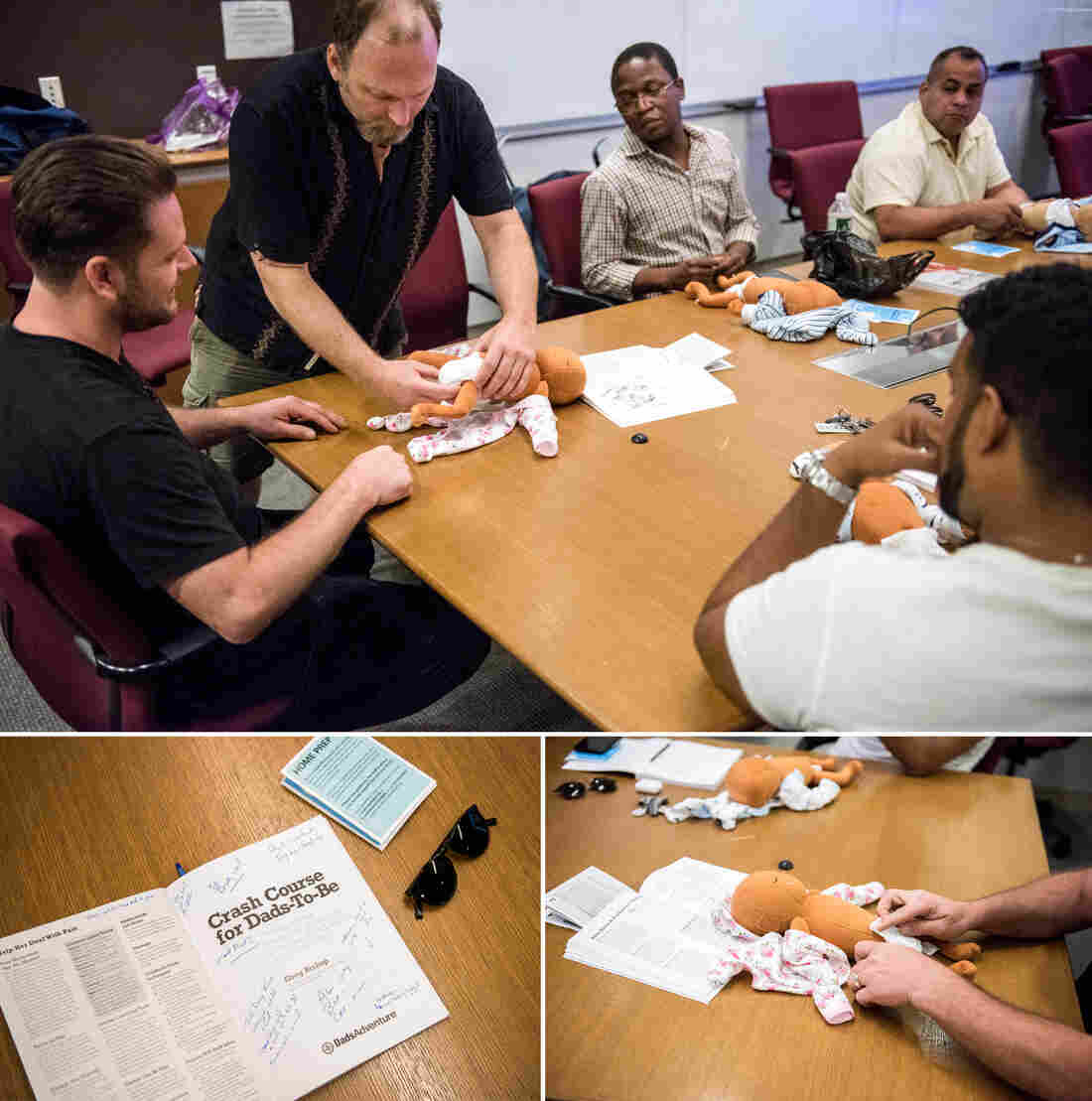

Joe Bay (center), coach of a New York City “Bootcamp for New Dads,” instructs Adewale Oshodi (left) and George Pasco in how to cradle an infant for best soothing.

Jason LeCras for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jason LeCras for NPR

“Before I became a dad, the thought of struggling to soothe my crying baby terrified me,” says Yaka Oyo, 37, a new father who lives in New York City. Like many first-time parents, Oyo worried he would misread his newborn baby’s cues.

“I pictured myself pleading with my baby saying, ‘What do you want?’ “

Oyo’s anxieties are common to many first-time mothers and fathers. One reason parents-to-be sign up for prenatal classes, is to have their questions, such as ‘What’s the toughest part of parenting?’ and ‘How do I care for my newborn baby?’ answered by childcare experts.

However, though prenatal classes show both parents how to swaddle, soothe, and comfort their infants, they are usually aimed mostly at the mom — discussing her shifting role and how to cope with the bundle of emotions motherhood brings.

With that focus, “Dad’s parenting questions can fall to the wayside,” says Dr. Craig Garfield, a professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and an attending physician at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago. And the lack of attention to a new father’s needs can have ripple effects that impact the whole family — in the short-run and later, Garfield says.

Around the U.S., a number of health care providers, such as Garfield in Chicago and the non-profit ‘Bootcamp for New Dads’ in New York City, have begun trying to change their approach to such classes. Some go so far as to hold single-sex prenatal classes specifically for men.

“Because each parent holds a separate role in their child’s life, expectant mothers and fathers may seek different answers to their parenting questions,” Garfield explains.

Indeed, raising children is nothing new, but parenting culture has shifted in the U.S., over time. For instance, compared to parents of the 1960s, today’s mothers and fathers tend to focus more of their time and money on their children, a recent study suggests, adopting what sociologists call an “intensive parenting” style.

Parental worries about their kids’ academic success and future financial stability may drive this parenting philosophy, researchers say.

These mounting responsibilities can stress the family, which is why mothers and fathers may feel eager to define their parenting roles. While a new mother’s role in modern society is often directed by her baby’s needs to breastfeed, cuddle and sleep; a new father’s role isn’t always spelled out.

Dads-to-be learn how to change diapers in the workshop for and by men, at the New York Langone Medical Center. Participants say they appreciate the combination of concrete skills and candid advice from other fathers.

Jason LeCras for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jason LeCras for NPR

“Even though fathers are far from secondary in their children’s lives, they may feel uncertain about their place in the family,” says Julian Redwood, a psychotherapist in San Francisco who counsels dads.

In fact, Garfield says, as they await their baby’s arrival, men, like women, often worry about the hands-on tasks of childcare, how to raise well-adjusted kids, and about how to cope with sleep deprivation, especially after they return to work.

Addressing those concerns early helps dads get involved with parenting from the outset, and that bolsters the whole family’s health — maybe especially the baby’s — according to research by pediatricians and child psychologists. For example, a 2017 study found that the amount of hands-on, sensitive engagement dads were observed to have with babies at age 4 months and 24 months correlated positively with the baby’s cognitive development at age 2.

Early father involvement also benefits the health of the child by fostering sturdier father-child bonds and psychological resilience, researchers say.

Oyo says the three-hour-long, Sunday Bootcamp for New Dads session he attended at NYU Langone Medical center, helped ease his early fears. At the peer-led workshop, “I learned babies communicate through crying,” he says, “and that they usually cry for four reasons — which made infant care seem less scary.”

Joe Bay, a 44-year-old father who lives in Clifton, N.J., was the session’s coach. Calling the course a “bootcamp” acknowledges the ambivalent relationship dads may feel between childcare duties and societal views of masculinity, Bay says. It also speaks to the practicality of what the men can expect to learn — how to hold a tiny baby, for example, or how to soothe a crying infant.

Participants also learn how parenthood can rock their partner’s well-being — and upend their own emotional health, as it rattles their sense of identity.

Future fathers get a chance in the course to question Bootcamp grads. Bay says he finds many fathers-to-be more willing to open up when their partners are absent. Oyo concurs.

“I met a dad who seemed like a ‘pro’ with his infant son, which was reassuring,” Oyo says. Learning from that man how to change a diaper and how to swaddle a baby, he says, helped him stay calm later, when facing his own wailing daughter. In the class he’d learned how to “read her cues.”

As the dads get more secure in their parenting skills, the moms usually become less anxious, too. And that’s crucial in making sure a behavioral tendency family scientists call “maternal gatekeeping” doesn’t derail the family system.

“Maternal gatekeeping encompasses a set of behaviors that mothers may use — consciously or unknowingly — that limit the father’s involvement with their children,” explains Anna Olsavsky, a doctoral candidate in human development and family science at The Ohio State University, and lead author of a 2019 study of how such “gatekeeping” influences a budding family.

Gatekeeping behaviors can be small but powerful: micromanaging dad’s interaction with the baby, for example, or criticizing how he holds or feeds the child.

Though fathers have always been somewhat involved in their children’s care, Olsavsky says, society still deems mothers “childcare experts.”

“That portrayal can lead dads to be socialized into supportive parenting roles” she adds — in other words, they take a step back.

In their most recent study, Olsavsky and her colleagues found that men who felt welcomed by their partners to participate in child rearing felt more connected to their partners, and were more likely to identify as equally involved and responsible co-parents.

Guests of the class Jesse Applegate (center) and his son, Jacob, field questions from Saxon Eldridge (left), and Chris De Souza (right) about what to expect after the baby’s born.

Jason LeCras for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jason LeCras for NPR

Oyo, whose daughter is now nine-months-old, says the bootcamp helped him take an active lead in parenting. It was also a relief to his pregnant wife, he says, to see that he was studying up for fatherhood.

After the course,” Oyo says, “I shared everything I had learned, and once the baby was born, I became the trusted source for swaddling.”

Garfield tells prospective fathers that the art of proper swaddling, a method of wrapping babies that soothes them in the first couple of months, can be one of ‘dads secret parenting weapons.’ Additional tools include using a low voice to talk or sing to the baby, Garfield adds, or playing with the newborn during diaper changing time.

Learning these parenting techniques and the dynamics that develop when one new parent feels sidelined can be just as useful for adoptive parents and same-sex couples, Bay notes.

For all parents, raising children can feel a bit like being thrust into an ocean without knowing how to swim. But having an outlet where each caregiver can connect and learn from their peers helps make parenting less lonely. And it dismantles the myth of the ‘perfect parent.’

Greater parental harmony can help decrease spousal friction, which tends to rise when sleep deprivation and a lack of control are at an all-time high.

Reducing parental bickering pays off for the baby, too: Research suggests constant arguments can have an impact on a child’s brain development, disrupt healthy attachment, and raise a child’s risk of becoming anxious and depressed later in life.

Many mothers and fathers enter the wild ride of parenting hoping to be ‘expert parents.’ That’s a big mistake, Bay tells participants in his Bootcamp workshops.

“I always tell dads the goal isn’t to be ‘perfect,’ ” he says, “but ‘good enough.’ “

Juli Fraga is a psychologist and writer in San Francisco. You can find her on Twitter @dr_fraga.

Trump Administration Is In Court To Block Nation’s First Supervised Injection Site

Supporters of safe injection sites in Philadelphia rallied outside this week’s federal hearing. The judge’s ultimate ruling will determine if the proposed “Safehouse” facility to prevent deaths from opioid overdose would violate the federal Controlled Substances Act.

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

Philadelphia could become the first U.S. city to offer opioid users a place to inject drugs under medical supervision. But lawyers for the Trump administration are trying to block the effort, citing a 1980s-era law known as “the crack house statute.”

Justice Department lawyers argued in federal court Thursday against Safehouse, the nonprofit organization that wants to open the site.

U.S. Attorney William McSwain, in a rare move, argued the case himself. He says Safehouse’s intended activities would clearly violate a portion of the federal Controlled Substances Act that makes it illegal to manage any place for the purpose of unlawfully using a controlled substance. The statute was added to the broader legislation in the mid-1980s at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic in American cities.

Safehouse argues the law does not apply because the nonprofit’s main purpose is saving lives, not providing illegal drugs. Its board members say that the “crack house statute” was not designed to be applied in the face of a public health emergency.

“Do you think that Congress would want to send volunteer nurses and doctors to prison?” asked former Philadelphia Mayor and Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell, who is on Safehouse’s board, after the hearing. “Do you think that’s a legitimate result of this statute? Of course not. No one could have ever contemplated that, ever!”

Safehouse earned the backing of Philadelphia’s mayor, health department, and district attorney, who announced they would support a supervised injection site in January 2018 as another tool to combat the city’s dire overdose crisis.

More than 1,100 people died of overdoses in Philadelphia in 2018 — an average of three people a day. That’s triple the city’s homicide rate.

In response, public health advocates and medical professionals teamed up with the operators of the city’s only syringe exchange to found Safehouse. They created a plan for its operations, and began scouting a location.

But the Trump Administration sued the nonprofit in February to block the supervised injection site from opening.

In June, the Justice Department filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings– essentially asking the judge to rule on the case based on the arguments that had already been submitted. Since then, a range of parties have filed amicus briefs in support of or in opposition to the site. Attorneys general, mayors, and governors from across the country filed briefs backing Safehouse, while several neighborhood associations in Kensington and the police union filed against it.

U.S. District Judge Gerald McHugh requested an evidentiary hearing to learn more about the nuts and bolts of how the facility would work, were it to open. At that hearing, in August, Safehouse’s legal team, led by Ilana H. Eisenstein, explained that Safehouse would not provide drugs, but that people could bring their own to inject while medical professionals stood by with naloxone, the overdose reversal drug. They said Safehouse would also be an opportunity for people to get access to treatment, if they were ready to commit to that.

Safehouse vice president Ronda Goldfein said the only difference between what Safehouse would do — and what’s already happening at federally sanctioned needle exchanges and the city’s emergency departments — is permit drug injection to happen in a safe, comfortable place.

“If the law allows for the provision of clean equipment, and the law allows for the provision of naloxone to save your life, does the law really not allow you to provide support in that thin sliver in between those federal[ly] permissible activities?” she said.

McSwain contends operating in that “sliver” is exactly what makes Safehouse illegal.

Much of the debate at Thursday’s hearing revolved around interpreting the word “purpose.” The statute in the Controlled Substances Act makes it illegal for anyone to “knowingly open … use or maintain any place … for the purpose of … using any controlled substance.”

The federal government says it’s simple: Safehouse’s purpose is for people to use drugs. McSwain conceded the facility will also provide access to treatment, but so does Prevention Point, the city’s only syringe exchange. Effectively, he argued, the only difference between Safehouse and what’s already going on elsewhere would be that people could inject drugs at Safehouse, which is prohibited by the statute.

“If this opens up, the whole point of it existing is for addicts to come and use drugs,” McSwain said.

Safehouse said its purpose is to keep people at risk of overdose from dying.

“I dispute the idea that we’re inviting people for drug use,” Eisenstein argued.

“We’re inviting people to stay to be proximal to medical support.”

McSwain conceded that if Safehouse were to offer the medical support without opening up a space specifically for people to use drugs, the statute would not apply.

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney spoke Thursday in support of the Safehouse injection site to reduce the number of deadly overdoses in Philadelphia. More than 1,100 people died of overdoses in the city in 2018 — an average of three people a day.

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

hide caption

toggle caption

Kimberly Paynter/WHYY

“If Safehouse pulled an emergency truck up to the park where people are shooting up, I don’t think [the statute] would reach that. If they had people come into the unit, that would be different,” he said. Mobile units and tents in parks are supervised injection models that other cities like Montreal and Vancouver have implemented.

Safehouse has also said it hasn’t ruled out the idea that it might incorporate a supervised injection site into another medical facility or community center, which would indisputably have other purposes, as well.

McSwain ultimately argued that Safehouse had come to the “steps of the wrong institution,” and that if it wanted to change the law, it should appeal to Congress. He accused Safehouse’s board of hubris, pointing to Safehouse president Jose Benitez‘s testimony at the August hearing, where he acknowledged that they hadn’t tried to open a site until now because they feared the federal government would think it was illegal and might shut it down.

“What’s changed?” asked McSwain. “Safehouse just got to the point where they thought they knew better.”

“Either that, or it’s the death toll,” Judge McHugh replied.

Supervised injection sites are used widely in Canada and Europe, and studies have shown that they can reduce overdose deaths and instances of injection-related diseases like HIV and hepatitis C. San Francisco, Seattle, New York City, Ithaca, N.Y., and Pittsburgh, Pa., among other U.S. cities, have expressed interest in opening a similar site, and are watching the Philadelphia case closely. In 2016, a nonprofit in Boston opened a room where people can go after injecting drugs, to ride out their high. The room has nurses equipped with naloxone standing by.

The Justice Department’s motion for the judge to rule on the pleadings is still pending. McHugh could decide he now has enough information to issue a ruling, or he might request more hearings, arguments or a full fledged trial.

Safehouse’s legal team said this week that if the judge rules in its favor, it might request a preliminary injunction in the form of relief — to allow the facility to open early.

“We recognize there’s a crisis here,” said Safehouse’s Goldfien. “The goal would be to open as soon as possible.”

This story is part of NPR‘s reporting partnership with WHYY and Kaiser Health News.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with WHYY and Kaiser Health News.

Treatment Limitations For Physicians With Opioid Addictions

Opioid addiction can happen to anyone, and that includes doctors and nurses. But unlike the general population, they are often barred from medications like methadone, the gold standard of treatment.

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

When doctors and nurses become addicted to opioids and they get caught, they have to follow strict treatment guidelines to get their licenses back. Often that means they’re not allowed to use the so-called gold standard of treatment – medications such as methadone and Suboxone. NPR’s Selena Simmons-Duffin has more.

SELENA SIMMONS-DUFFIN, BYLINE: Here’s how this played out for Dr. Peter Grinspoon. He got addicted to Vicodin in med school and still had an opiate addiction five years into practice as a primary care physician. Then, back in February 2005, he got in trouble.

PETER GRINSPOON: In my addicted mind frame, I was writing prescriptions for a nanny who had since returned back to another country. And it didn’t take the pharmacist long to figure out that I was not a 19-year-old nanny from New Zealand.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: One day during lunch, he says the state police and the DEA showed up at his medical office.

GRINSPOON: I start going, oh, I’m glad you’re here. You know, how can I help you? And they’re like, Doc, cut the crap. We know you’re writing bad scripts.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: He was fingerprinted the next day, charged with three felony counts of fraudulently obtaining a controlled substance. And he got referred to his state’s physician health program or PHP. They work with state licensing boards. If you follow the treatment and monitoring plan they set up for you, they’ll recommend to the board that you get your medical license back.

GRINSPOON: The PHPs basically say, do whatever we say, or we won’t give you a letter that will help you get back to work. So they put a gun to your head.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: And, Grinspoon says, they gave him very little choice. To avoid a criminal record, he needed to spend 90 days at an inpatient center in Virginia.

GRINSPOON: Why would you send this Jewish atheist to a Christian rehab place in Virginia? Didn’t make any sense. I was just sitting there listening to people recite the Lord’s Prayer and hold hands. They took me cold turkey off all my medications. It was completely insane.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: He says medication-assisted treatment with Suboxone or methadone was off the table for him. Those medications are similar to opioids and work by suppressing cravings to the abused drug. Physician health programs, he says, effectively banned the use of these medications in the treatment plans they set up for physicians like him.

GRINSPOON: Why on earth would you deny physicians who are under so much stress and who have a higher access – they have free refills – and they have a higher addiction rate, why would you deny them the one life-saving treatment for this deadly disease that’s killing more people in this country every year than died in the entire Vietnam War?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Grinspoon recovered despite what he called several awful rehabs. Today, he’s a licensed primary care doctor and teaches at Harvard Medical School. He also wrote a book about his experience with addiction called “Free Refills.” Now, this was over a decade ago, but Dr. Sarah Wakeman – also at Harvard – says most physician health programs still don’t promote medication and treatment for addiction.

SARAH WAKEMAN: The sort of general standard of care is to send people to abstinence-based residential treatment programs that don’t offer medication treatment.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: She just co-authored a piece in The New England Journal of Medicine which called this, quote, “bad medicine, bad policy and discriminatory.”

WAKEMAN: I think the underlying issue is stigma and the sort of misunderstanding of the role of medication and this idea that a non-medication-based approach is somehow better than someone taking the medication to control their illness.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: So what do the institutions getting blamed here – physician health programs – have to say about all this? Dr. Christopher Bundy runs Washington state’s PHP and the federation of all the state PHPs. He says it’s true that these medications aren’t often used, but that’s not because of stigma or ideology.

CHRISTOPHER BUNDY: Proceeding with caution is understandable and warranted.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: He says medication may be the gold standard of treatment in the general population, but there should be an asterisk when it comes to so-called safety sensitive workers, not just health care providers, also pilots, for instance. He says the concern is that these medications can affect cognition. So the idea of people caring for patients while taking something like buprenorphine makes some people nervous.

BUNDY: We only need one bad outcome involving a physician with substance use disorder who’s back to work, then immediately the PHP is under the microscope.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: He says then the criticism would be, how could you let that doctor work on a medication that could have played a role in that bad outcome? He doesn’t know of a case where that’s happened. Wakeman and her co-authors also argue there isn’t clear evidence that these medications do impair cognition. Still, that fear could be what’s driving the reluctance here. Bill Kinkel is currently navigating all of this. He lives outside Philadelphia.

BILL KINKLE: I’m a nurse, and I’m also a person in sustained recovery from opioid use disorder.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: He’ll be eligible to practice nursing again next fall after three years of documented sobriety. And he’s public about being in recovery. He even has a podcast. When he was addicted, he said he was under a strong impression he wouldn’t be able to go back to nursing if he was in a medication-assisted treatment program. So he went to abstinence-based rehabs over and over again. And over and over again, as soon as the rehab ended, he relapsed.

KINKLE: A lot of those I overdosed. And had my wife not found me on the floor and been able to take care of me, I very well may have died. And all that possibly could have been mitigated had I gotten either buprenorphine or methadone.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: He doesn’t fault the PHPs or the licensing boards for these policies even though he thinks they put his life at risk. He thinks stigma against those with addiction is so ingrained in our culture, there’s no one institution to blame. What’s important is that this changes, he says, and health professionals have access to all possible tools in recovery.

Selena Simmons-Duffin, NPR News.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

U.S. Authorities Reconsider Some Requests To Stay From Immigrants Seeking Medical Aid

Immigration authorities are reconsidering some requests from migrants to be allowed to stay in the U.S. to get medical treatment. But others hoping to get care here could be facing deportation.

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Immigration authorities are now reconsidering some requests from immigrants to stay in the U.S. for medical treatment. This is giving hope to those who were recently denied. But as WBUR’s Shannon Dooling reports, other immigrants hoping to get lifesaving care here could still be facing deportation.

SHANNON DOOLING, BYLINE: On the 10th floor of a Boston hospital, a software engineer from Morocco describes his quest to get treatment for a rare vascular tumor. He says he consulted doctors in Belgium, Germany and South Korea, but they didn’t want to risk the surgery.

MK: I do tests, and then they said, like, we’re sorry. We can’t do that surgery because we’ll kill you. And then I’ve been looking in research papers, and then I found two doctors here in Boston.

DOOLING: The 33-year-old struggles to lift himself in bed. He asked to use his initials, M.K., because he’s afraid speaking out will hurt his case. M.K. entered the country in 2017 on a tourist and medical visa. After extending his visa as many times as he could, he applied for what’s known as medical deferred action, knowing it was likely his last option to be able to stay in the country legally. Last week, he read WBUR’s report that U.S. Customs and Immigration Services was sending letters to patients, denying requests to stay in the U.S.

MK: I called a family member. I was like, check out the mail. And surprise, surprise, there’s the letter.

DOOLING: The agency told him he had 33 days to leave the country. He says he got the news on the same day his doctor suggested yet another surgery. Earlier this week, Customs and Immigration Services ended the medical deferrals with no public announcement, just denial letters. In the future, officials say, any immigrants facing deportation can ask Immigration and Customs Enforcement for a delay. In a partial reversal, USCIS then said it would consider cases that were pending as of August 7. M.K. says he hopes the federal government does the right thing.

MK: It’s impossible for me to go back. It will be like a death sentence.

DOOLING: Sixteen-year-old Jonathan Sanchez has cystic fibrosis. His family received the same denial letter sent to M.K. and others around the country.

JONATHAN SANCHEZ: Every night, I start woken up, like, at 2:55, 3 a.m., thinking, I will wake up tomorrow. I won’t. I’ll be alive. I’ll be dead. What will happen to me?

DOOLING: Jonathan and his family came to the U.S. on tourist visas in 2016. They left their home country of Honduras, seeking treatment at Boston Children’s Hospital. Their medical deferred action request, like M.K.’s, should now be reopened. Gary Sanchez, Jonathan’s father, breaks down when he talks about his son’s future, saying he wants to see him grow up.

GARY SANCHEZ: I have a dream that one day I can see to my son, like, a man with a wife, children.

DOOLING: He says his daughter died in Honduras of cystic fibrosis. He says doctors there had no idea how to treat her condition. On her death certificate, he says, the cause was left blank.

G SANCHEZ: I don’t want that my son die because he is all my life.

DOOLING: There’s no guarantee the Sanchez family and M.K. will be approved to stay. But for now, they have something to hope for.

For NPR News, I’m Shannon Dooling in Boston.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

When Employer Demands Clash With Health Care Obligations

NPR’s Steve Inskeep talks to Paul Spiegel, one of several doctors at Johns Hopkins University arguing that physicians who work in immigration detention centers could be violating the Hippocratic Oath.

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

Many people know a physician’s Hippocratic oath. It’s often summarized by the phrase first, do no harm. But what about when patients are detainees in U.S. immigration centers? A group of doctors is asking if it is ethical for doctors to agree to serve in those detention centers. Paul Spiegel of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health wrote about this in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

What is wrong with a physician thinking about going into an immigration detention facility to administer to children?

PAUL SPIEGEL: Nothing. In fact, I think it’s very important and a worthwhile endeavor to do so. The issue is rather more will a physician be able to fulfill his or her Hippocratic oath by having the independence to be able to provide the standard of care that is accepted and recommended.

INSKEEP: Why wouldn’t they have independence?

SPIEGEL: Well, there’s something called dual loyalty where the loyalty for the physician is first and foremost to the patient, but a physician, unless they’re working independently, is also working for an organization. And in this case, we have to look at, for the Department of Homeland Security, will they allow – will their decisions and the managers allow the clinicians to be able to provide the latest standard of care?

INSKEEP: Can you give me an example in which the concerns of the Department of Homeland Security would override a physician’s independent judgment of what’s best for a patient?

SPIEGEL: So we’ve seen in some detention facilities hygiene has been not acceptable in terms the provision of soap, water and sanitation. And the latest, of course, is concerns that some children have died from influenza. And then recently the Customs and Border Patrol has said that they will not provide influenza vaccines to people in their detention facilities.

INSKEEP: So there may be circumstances of very short-term detention under proper conditions that would seem fine to you, but there are many other circumstances you think doctors should have nothing to do with.

SPIEGEL: Correct, or doctors need to be able to speak out when they see something is not being handled properly. And so it’s why we’re also calling for an external committee to document what the standards are and then to be able to make their findings public.

INSKEEP: Suppose that an individual doctor is subscribing to your advice, wants to keep their Hippocratic Oath and the conditions just don’t exist. And the choice is either I as a doctor go in and do what help I can or I just stay away. Would you tell me to stay away?

SPIEGEL: Yes – very difficult situation. There needs to be some care. And so I don’t think we’re advocating to say unless health care professionals can fulfill their Hippocratic oath that they should all walk out and therefore no care should be delivered. We are hoping that Congress will ensure that there are changes so that doctors can work independently in those situation and ensure that the standards are being met.

INSKEEP: Did you as a physician lose any sleep while trying to think through this problem?

SPIEGEL: (Laughter) Because of my background of working in places in the Rwandan genocide and in Syria, it’s not something new for us to think through. But it’s been a little bit more disturbing to see these issues occur in the United States.

INSKEEP: Paul Spiegel of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Spiegel, thanks so much.

SPIEGEL: Thank you very much, Steve.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Report: Hundreds Of Florida Nursing Homes Fall Short Of Post-Irma Regulations

NPR’s Michel Martin talks with reporter Elizabeth Koh about how Florida nursing facilities are preparing — or not — for intense hurricanes.

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

Now staying here in Florida, residents may be spared a direct hit from Dorian, but forecasters say dangerous storm surges, hurricane-force winds and power outages are still expected. For Floridians, the memory of Hurricane Irma two years ago is still fresh, in part because at least 84 people in the state died as a result of the storm. Twelve of those deaths occurred at a nursing home in Hollywood, Fla., near Fort Lauderdale after the storm knocked out power to the facility’s air conditioning system. On Tuesday, four employees of the center were charged with aggravated manslaughter in connection with those deaths.

That tragedy raises the question of whether the state is better prepared today, especially in caring for vulnerable residents. A Miami Herald report found that hundreds of nursing homes do not meet new requirements put in place since Hurricane Irma. Miami Herald reporter Elizabeth Koh is with us now from Tallahassee to tell us more.

Elizabeth, thanks so much for joining us.

ELIZABETH KOH: Thanks for inviting me.

MARTIN: So, Elizabeth, has the state taken steps since Hurricane Irma to ensure that facilities like nursing homes can continue to care for residents in the event of a major hurricane? Are they ready?

KOH: The biggest thing that the state did after Irma was to pass regulations last year shortly after the storm hit to say that nursing homes and assisted living facilities needed backup power, specifically for their air conditioning, which is where the Hollywood Hills nursing facility failed. The regulations call for additional fuel storage in addition to powerful generators that can keep those temperature facilities running. And that was supposed to go into implementation at the beginning of last year’s hurricane season.

MARTIN: Last year’s hurricane season – so did it? I mean, are these facilities ready?

KOH: Hundreds of facilities needed more time. They cited delays with local governments that required additional permits, backlogs and contractors, difficulty getting the equipment installed. When we’re talking about large nursing home facilities, we’re talking about some pretty powerful, substantial generators that need concrete pads to sit on, things like that. So the state gave them an extension until the end of the year.

MARTIN: So do you have a sense of whether the staff at these facilities and the families of the residents – do they feel prepared for the storm?

KOH: That’s something that the state is trying to check. Unfortunately, as we learned in Irma, that’s something that can be difficult to determine with full certainty. The Hollywood Hills nursing facility, as we discussed, is a facility that had a generator on the premises. It just didn’t power their air conditioning. It had an emergency plan, like a lot of nursing home facilities have now. But that was a plan that wasn’t very thoroughly vetted by county officials.

So the question of how safe nursing home facilities actually are – that’s something that we’re seeing local officials do site checks and calls to see if they can establish generator statuses at various facilities and ensure the safety of residents. But if you are concerned about a family member who is at a facility, it’s worth calling and checking and asking how they’re preparing for this storm.

MARTIN: Are there any other lessons that the states learned from the tragedy that occurred in Hollywood Hills? Is there any – are there any other steps that they’re taking to give the public confidence that something like this won’t happen again?

KOH: They’ve put out a new website – it’s fl-generator.com – that gives the public an opportunity to look at what kind of generator status is on file with the state – whether they have a permanently installed generator, whether it’s a temporary generator on site, off site. So that’s a resource for the public.

The state has also promised that they will do spot checks after the storm to make sure that facilities that have gotten generators have those generators up and running. We’ve been told that the state has stockpiled additional generators in case some of those generators fail so that they have backups. And we’re told that the Department of Health is also helping with that, too – the State Department of Health.

MARTIN: That was Miami Herald reporter Elizabeth Koh joining us from WFSU in Tallahassee, Fla.

Elizabeth, thanks so much for joining us, and thanks for your reporting.

KOH: Thank you very much.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

For 2 Nurses, Working In The ICU Is ‘A Gift Of A Job’

Kristin Sollars (left) and Marci Ebberts say nursing is more than just a job. “Sometimes I wonder why everyone in the world doesn’t want to be a nurse,” Sollars says.

Emilyn Sosa for StoryCorps

hide caption

toggle caption

Emilyn Sosa for StoryCorps

For nurses Kristin Sollars and Marci Ebberts, work is more than just a job.

“Don’t you feel like you’re a nurse everywhere you go?” Sollars, 41, asked Ebberts, 46, on a visit to StoryCorps in May.

“I mean, let’s be honest, every time we get on a plane you’re like, E6 didn’t look good to me. Keep an eye out there.”

Sollars and Ebberts have grown so close while working together that they’ve come to call themselves “work wives.” They first met in 2007, working side by side in the intensive care unit at Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo.

Now they work closely as nurse educators at the hospital, training other nurses in critical care.

“Between us, we’ve taken care of thousands of critically ill patients,” Ebberts said. “You carry a little bit of them with you. And they shape you.”

Sollars and Ebberts reflect on how their work influences their memories.

“When I think about that patient, that is the most seared in my brain, I know exactly what bed but I cannot tell you the patient’s name,” Sollars said. She goes on to remember a particularly unforgettable case: “I always think about CCU (Coronary Care Unit) Bed 2.”

The patient had a cardiac arrest. “We code him, and we get that heart rate back,” she said, describing their resuscitation efforts that stabilized the patient.

“And that was just the first of a dozen times that he coded,” Ebberts remembered.

All the while, his wife was by his side.

“We were giving her the bad prognosis. Things were looking really bad, and she said, ‘Can I be in bed with him?’ ” Sollars said.

But the nurses saw that as a risk. “This man’s got everything we’ve got in the hospital attached to him,” Sollars recalled.

“So many wires and tubes and monitors,” Ebberts added.

Still, they proceeded carefully, slowly lifting everything so she could wiggle in next to him.

“I can just remember her sobbing, saying, you know, I wasn’t a good enough wife. I should have loved you better,” Sollars said.

When the patient again suffered an irregular, life-threatening heart rhythm called ventricular fibrillation, Sollars and Ebberts started another round of chest compressions.

But this time, the patient’s wife asked the nurses to stop trying to resuscitate him. “We’re gonna let him go next time he does that,” Ebberts remembers his wife saying.

Sollars says the rewarding part as a nurse is caring for patients and their families during these crucial life moments, as difficult as they can be to witness.

“To be with people and to create those environments where they get to say their unfinished business to their husband — it’s such a gift of a job,” Sollars said. “Sometimes I wonder why everyone in the world doesn’t want to be a nurse.”

Sollars says nursing levels her sense of what’s important.

“It does impact the way we see the entire world. That person in front of us in the grocery store is all worked up about how that guy bagged their groceries,” she said.

“Nobody’s dying,” Ebberts said, “until someone is. And then we’re ready.”

Audio produced for Morning Edition by Aisha Turner and Camila Kerwin.

StoryCorps is a national nonprofit that gives people the chance to interview friends and loved ones about their lives. These conversations are archived at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, allowing participants to leave a legacy for future generations. Learn more, including how to interview someone in your life, at StoryCorps.org.

Bill Of The Month: Estimate For Cost Of Hernia Surgery Misses The Mark

Before scheduling his hernia surgery, Wolfgang Balzer called the hospital, the surgeon and the anesthesiologist to get estimates for how much the procedure would cost. But when his bill came, the estimates he had obtained were wildly off.

John Woike for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

John Woike for Kaiser Health News

From a planning perspective, Wolfgang Balzer is the perfect health care consumer.

Balzer, an engineer, knew for several years he had a hernia that would need to be repaired, but it wasn’t an emergency, so he waited until the time was right.

The opportunity came in 2018 after his wife, Farren, had given birth to their second child in February. The couple had met their deductible early in the year and figured that would minimize out-of-pocket payments for Wolfgang’s surgery.

Before scheduling it, he called the hospital, the surgeon and the anesthesiologist to get estimates for how much the procedure would cost.

“We tried our best to weigh out our plan and figure out what the numbers were,” Wolfgang said.

Share Your Story And Bill With Us

If you’ve had a medical-billing experience that you think we should investigate, you can share the bill and describe what happened here.

The hospital told him the normal billed rate was $10,333.16, but that Cigna, his insurer, had negotiated a discount to $6,995.56, meaning his 20% patient share would be $1,399.11. The surgeon’s office quoted a normal rate of $1,675, but the Cigna discounted rate was just $469, meaning his copayment would be about $94. (Although the Balzers made four calls to the anesthesiologist’s office to get a quote, leaving messages on the answering machine, no one returned their calls.)

Estimates in hand, they budgeted for the money they would have to pay. Wolfgang proceeded with the surgery in November, and, medically, it went according to plan.

Then the bill came.

The patient: Wolfgang Balzer, 40, an engineer in Wethersfield, Conn. Through his job, he is insured by Cigna.

Total bill: All the estimates the Balzers had painstakingly obtained were wildly off. The hospital’s bill was $16,314. After the insurer’s contracting discount was applied, the bill fell to $10,552, still 51% over the initial estimate. The contracted rate for the surgeon’s fee was $968, more than double the estimate. After Cigna’s payments, the Balzers were billed $2,304.51, much more than they’d budgeted for.

Service provider: Hartford Hospital, operated by Hartford HealthCare

Medical procedure: Bilateral inguinal hernia repair

What gives: “This is ending up costing us $800 more,” said Farren, 36. “For two working people with two children and full-time day care, that’s a huge hit.”

When the bill came on Christmas Eve 2018, the Balzers called around, trying to figure out what went wrong with the initial estimate, only to get bounced from the hospital’s billing office to patient accounts and finally ending up speaking with the hospital’s “Integrity Department.”

They were told “a quote is only a quote and doesn’t take into consideration complications.” The Balzers pointed out there had been no complications in the outpatient procedure; Wolfgang went home the same day, a few hours after he woke up.

The couple appealed the bill. They called their insurer. They waited for collection notices to roll in.

Hospitalestimates are often inaccurate and there is no legal obligation that they be correct, or even be issued in good faith. It’s not so in other industries. When you take out a mortgage, for instance, the lender’s estimate of origination charges has to be accurate by law; even closing fees — incurred months later — cannot exceed the initial estimate by more than 10%. In construction or home remodeling, while estimates are not legal contracts, failure to live up to them can be a basis for liability or a “claim for negligent misrepresentation.”

In this case, Hartford Hospital produced an estimate for Balzer’s laparoscopic hernia repair, CPT (current procedural terminology) code 49650.

The hospital ran the code through a computer program that produced an average of what others have paid in the past. Cynthia Pugliese, Hartford Health’s vice president of revenue cycle, said the hospital uses averages because more complicated cases may require additional supplies or services, which would add costs.

“Because it was new, perhaps the system doesn’t have enough cases to provide an accurate estimate,” Pugliese says. “We did not communicate effectively to him related to his estimate. It’s not our norm. We look at this experience and this event to learn from this.”

Efforts to make health care prices more transparent have not managed to bring down bills because the different charges and prices given are so often inscrutable or unreliable, says Dr. Ateev Mehrotra, an associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School.

“The charges on there don’t make any sense. All it does is, people get pissed off,” Mehrotra said. “The charge has no link to reality, so it doesn’t matter.”

Resolution: “Because I roll over more easily than my wife does, I’m of the mindset to pay it and get done with it,” Wolfgang said. “My wife says absolutely not.”

Investigating prices, dealing with billing departments and following up with their insurer was draining for the Balzers.

“I’ve been tackling this since December,” Wolfgang says. “I’ve lost two or three days in terms of time.”

For the Balzers, there’s a happy ending. After a reporter made inquiries about the discrepancy between the estimate and the billed charges — six months after they got their first bill — Pugliese told them to forget it. Their bill would be an “administrative write-off,” they were told.

“They repeatedly apologized and ended up promising to adjust our bill to zero dollars,” Wolfgang wrote in an email.

The takeaway: It is a good idea to get an estimate in advance for health care, if your condition is not an emergency. But it is important to know that an estimate can be way off — and your provider probably is not legally required to honor it.

Try to request an estimate that is “all-in” — including the entire set of services associated with your procedure or admission. If it’s not all-inclusive, the hospital should make clear which services are not being counted.

Having an estimate means you can make an argument with your provider and insurer that you shouldn’t be charged more than you expected. It could work.

Laws requiring at least a level of accuracy in medical estimates would help. In a number of other countries, patients are entitled to accurate estimates if they are paying out-of-pocket.

Most patients aren’t as proactive as the Balzers, and most wouldn’t know that the hospital, surgeon and anesthesiologist would all bill separately. And most wouldn’t fight a bill that they could afford to pay.

The Balzers say they wouldn’t have changed their medical decision, even if they had been given the right estimate at the beginning. It’s the principle they fought for here: “There’s no other consumer industry where this would be tolerated,” Farren wrote in an email.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

Purdue Pharma Considers Converting To A Public Trust Amid Lawsuits Over Opioid Crisis

NPR’s Ailsa Chang talks with Charles Tatelbaum, director at Tripp Scott law firm, about what the Purdue Pharma settlement would mean for the company, the plaintiffs and the Sackler family.

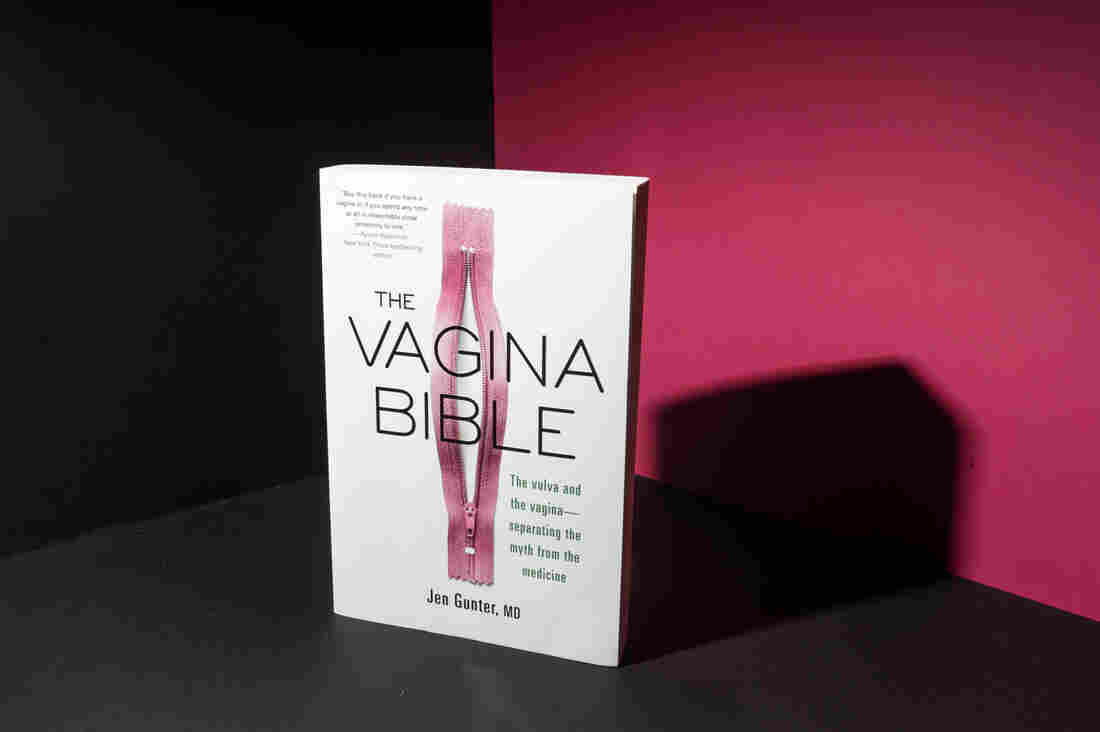

‘Vagina Bible’ Tackles Health And Politics In A Guide To Female Physiology

In The Vagina Bible, gynecologist Jen Gunter dispels myths about the female body.

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Rizzo/NPR

Hey, women: Dr. Jen Gunter wants you to understand your own vagina.

The California gynecologist is on a quest to help women get the facts about their own bodies. It isn’t always easy. In an era of political attacks on women’s reproductive choices and at a time when Internet wellness gurus are hawking dubious pelvic treatments, getting women evidence-based information about their health can be a challenge, she says.

But Gunter isn’t backing down.

“I’m really just trying to give women information so they can make informed choices,” Gunter tells NPR. “Misinformation is the opposite of feminism. Making an empowered decision requires accurate information.”

Gunter started her blog, Wielding the Lasso of Truth, almost 10 years ago, writing on topics that range from abortion politics to the risks to women who eat the placenta after childbirth (yes, really). She rose to Internet fame as she took on the very public task of debunking several treatments touted by Gwyneth Paltrow and her wellness empire, Goop — including $66 jade eggs designed to be inserted into the vagina and a treatment known as “vaginal steaming.” Gunter now writes a column about women’s health for the New York Times.

She spoke about her new book, The Vagina Bible, with NPR contributor and family physician Mara Gordon. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Gunter started a blog almost 10 years ago writing about women’s health topics. She now has a column on women’s health for The New York Times.

Jason LeCras

hide caption

toggle caption

Jason LeCras

The Vagina Bible is coming out at a moment where women’s reproductive health in the U.S. is a huge political issue. Yet this book is more clinical than political. What made you want to take this approach?

I found myself debunking the same myth over and over again: “No, you shouldn’t put yogurt in your vagina. No, you shouldn’t put garlic in your vagina.” I got really fixated on this idea that I wanted women to have a textbook so they could divorce themselves from the cacophony that’s online. … When I went through medical school, Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine was the internal medicine Bible. Williams Obstetrics was my obstetrics Bible. That’s how I referred to my resources that I went to over and over again.

You talk about how women are conditioned to think their vaginas are abnormal, saying, “There’s a lot of money in vaginal shame.” You argue that it’s related to marketing of procedures like vaginal rejuvenation, or expensive objects women are told to put in their vaginas, or cleansing gels and wipes they’re encouraged to use. What’s going on?

I have noticed a huge increase in what I can only describe as women being “vaginally hyperaware.” I did a fellowship in infectious diseases in 1995, and since then, I have specialized in vaginitis — irritation of the vagina. The number of patients, the percentage that I see, who have nothing physiologically wrong with them has increased dramatically.

What do they tend to be experiencing?

I would say odor, volume of discharge. … Then there’s also this group of patients who are convinced they have yeast infections. They definitely have something causing their symptoms that’s not yeast — usually chronic vulvar irritation. So what happens when someone comes in and the doctor can’t find anything wrong is that many doctors will just give antibiotics or give antifungals.

Do your patients ever feel like you’re dismissing or not believing their symptoms?

For so many years, women have had their symptoms dismissed. They’ve been told that their normal bodies are wrong. And so there are all these complex messages. I really try to pin down and ask them, “OK, so what’s your bother factor? And then let’s work it out from there.”

An interesting theme in the book is something I see in my own primary care practice: the “well, it can’t hurt” phenomenon. For example, a doctor might tell a woman to only wear white cotton underwear if she’s having recurrent yeast infections, because “Well, it can’t hurt, right?” Doctors suggest a lot of treatments that don’t have any evidence behind them. What’s going on?

I think that it’s really hard for doctors to say, “I don’t know.” That’s something that I learned being a parent of children who had unfixable medical conditions. [My] son has cerebral palsy, and [my] other son has a heart condition that can’t be fixed. … The most valuable thing, actually, a physician ever told me when I was struggling with my kids was, “You know, if we had better therapies to offer you, we’d be offering them to you.” And that was a really profound moment.

How do you approach this as a clinician, when you can’t offer your patients a quick-fix treatment with rigorous research behind it?

I actually have a lot of therapies for a lot of conditions that people think are impossible to treat. But I do get a lot of patients saying, “Is this the best you have?” And I say, “Yes. Yes, it is the best I have.” And I explain why.

Most people can understand the science behind what we’re offering. … The biggest issue is that we don’t have the time to explain it. If you’re only given seven minutes to explain to someone the complexities of chronic yeast infections — because actually, immunologically, it’s a little bit complex — the only way you can do it is in a horrible, patriarchal “Well, just do this” manner.

Let’s talk about your other specialty — women’s pelvic pain. Why is this so hard to treat?

Pain is so complex. When you explain it to patients, you have to be so careful, because it can sound like you are saying their pain is in their head, when that’s not what you mean. It’s in their nervous system. It’s physiologically very hard to explain.

Dealing with pain is very humbling as a physician. We’re really talking about improvement, not fixing. And that’s really very hard for people to accept. We have all of this cool medicine, all these advances, and we can’t fix pain. It’s frustrating.

Doctors don’t have a great track record of taking women’s pain seriously.

We know anxiety and depression amplify pain. It’s well-known. I work with a pain psychologist, and I’ll talk about mind-body medicine. When I say that, a patient often hears that I’m dismissing their pain. What I’m doing is actually taking it very seriously. … People come in and they want scalpels, right? They want a grand thing because when you have pain, it’s huge, it’s all-consuming. And you come in and you hear, “Wait, what? Physical therapy? And managing my anxiety? How can you fix my huge problem with these seemingly little things?” So when you have a huge problem, you think that you need a huge solution, like surgery, like an MRI, because those are big.

We doctors have had a strictly biomedical model for disease for a long time. It’s a pretty recent development that we consider sex, relationships, stress and even sexism within our purview. Do you feel like your patients are eager for you to address those things?

I think that women appreciate knowing the forces that led us here. … I want people to understand that the patriarchy has been everywhere. Medicine is part of everything. So of course medicine has patriarchy. … I personally don’t think that medicine is worse than anything else, but I do think that because medicine cares for people, we have the biggest duty to respond to it fast.

I think that a lot of women are really hungry for a woman physician to stand up and say, “Wait a minute. Wait, wait, wait. I know about women’s bodies. That’s not going to fly, because I know the physiology.”

What is the most absurd vaginal product that you’ve come across in your research?

Ozone getting blown into your vagina. It’s highly toxic for your lungs. … I can’t imagine what it does to your vagina.

Mara Gordon is a family physician in Camden, N.J., and a contributor to NPR. You can follow her on Twitter: @MaraGordonMD.