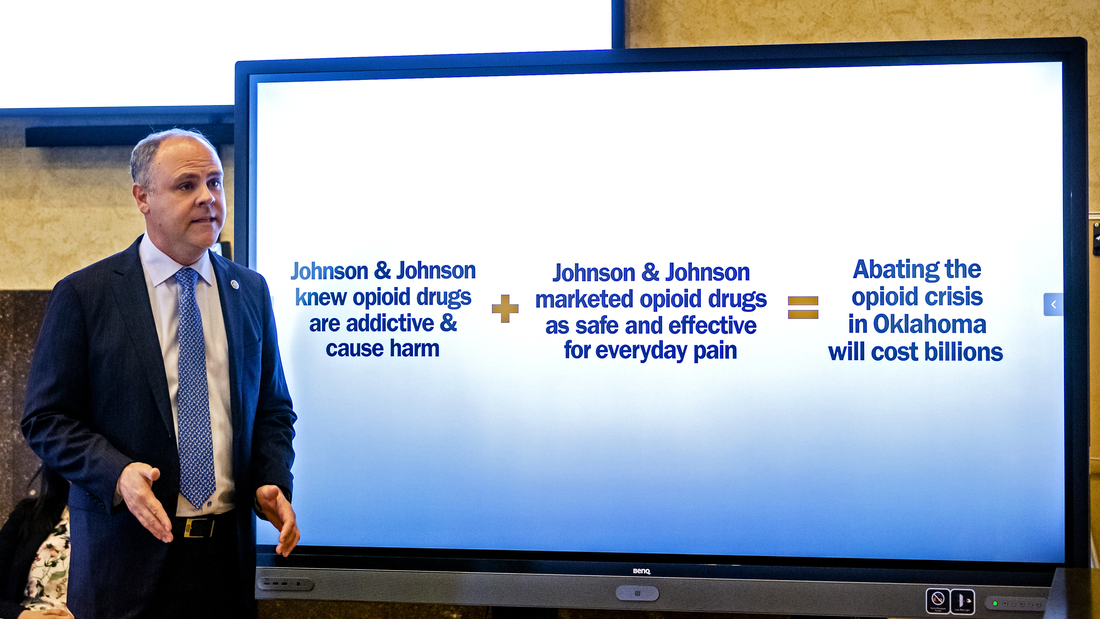

State’s attorney Brad Beckworth lays out one of his closing arguments in Oklahoma’s case against drugmaker Johnson & Johnson at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla. in July. The judge in the case ruled Monday that J&J must pay $572 million to the state.

Chris Landsberger/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/AP

Today, the judge hearing the opioid case brought by Oklahoma against the pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson awarded the state roughly $572 million.

The fact that the state won any money is significant — it’s the first ruling to hold a pharmaceutical company responsible for the opioid crisis.

But the state had asked for much more: around $17 billion. The judge found the drugmaker liable for only about 1/30 of that.

“The state did not present sufficient evidence of the amount of time and costs necessary, beyond year one, to abate the opioid crisis,” Judge Thad Balkman wrote in his ruling.

That’s the big reason for the discrepancy. The judge based his decision on one year of abatement. The state’s plan — and the basis of that $17 billion ask — was looking at abatement for the next three decades.

That 30-year plan was authored by Christopher Ruhm, a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Virginia. He says you can easily get into the billions when you consider the costs of dealing with this epidemic in the long term.

“Take one example,” Ruhm says. “Addiction treatment services, which includes a variety of things — that includes inpatient services, outpatient services, residential care. You’re talking a cost there on the order of $230 million per year. And so if you take that over a 30-year period — and then you discount it to net present value and all the things economists do — you come up with a cost for treatment services of just under $6 billion.”

Just that cost gets you more than a third of the way to $17 billion. The rest comes from all sorts of things, he says: public and physician education programs; treatment for babies who are born to mothers who used opioids; data systems for pharmacists to better track prescriptions grief support groups and more. Ruhm added up all those costs over 30 years, and got more than $17 billion.

“Let’s be clear,” he says. “It is a lot of money. It’s also a major public health crisis.” Nationally, 130 people, on average, die every day from opioid-related overdoses, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Ruhm suggests one year of funding for abatement won’t be nearly enough. “Many currently addicted individuals are likely to need medication-assisted treatment for many years, or even for decades. The same is true for many other aspects of the crisis,” he says.

Today’s verdict does not mean Oklahoma is now going to spend the $572 million dollars it was awarded on any particular abatement plan, assuming, even that it sees any of that cash — Johnson & Johnson’s attorneys say they will appeal Monday’s court decision.

Ultimately, it will be up to state officials and lawmakers to decide how to actually use any money the state gets. And that will probably be nowhere near Ruhm’s projection of what’s needed in the long term.

Health economist Kosali Simon at Indiana University says the $17 billion figure didn’t seem outsize to her.

“In general these numbers tend to be large because we’re thinking over a long time period; we’re thinking about a 30-year horizon,” she says. “There isn’t a vaccine or a one-time dose of medication that would completely heal everybody.”

Simon compares Ruhm’s report to what economists did after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 — estimating what it would cost to return the environment as closely as possible to its pre-spill condition.

Except in this case, there isn’t a single oil spill. There is an opioid epidemic in every state.

“This report is going to be a very important and useful baseline against which other states can consider their own situation,” says Simon.

Nationally, she says, it would cost much more than taking Oklahoma’s numbers and scaling them up to solve the problem. The country needs to invest in research on what treatment options work best, develop better addiction treatment drugs, et cetera.

Then there’s the question — once you’ve fully accounted for all these costs — of who should pay?

“The economist’s job is to think, ‘How much money does it take now to abate the setting?’ ” Simon says. “Whose pocket that should come from is an entirely different and — I think — much more difficult question for society to answer.”

Today the judge said a drugmaker should pay at least some of the costs of abating the crisis — at least for one year.

There are hundreds of other opioid cases around the country, and those judges might come to different conclusions.