By Amy Martin

Kevin Murphy says he is proud of what he and the other workers do at the Rosebud mine, including digging the coal and reclaiming the land afterward. Amy Martin/Montana Public Radio hide caption

itoggle caption Amy Martin/Montana Public Radio

Colstrip, Mont., is true to its name — it exists because of coal.

“Our coal’s getting deeper, like everywhere else, because everybody’s mining. They’re getting into the deeper stuff,” says Kevin Murphy, who has worked in the Rosebud Mine for 15 years running a bulldozer in the open pits.

Everything about the mine is enormous, especially the dragline, a machine as big as a ship with a giant boom that extends 300 feet up into the air. The dragline perches on the lip of the pit, scraping away hundreds of feet of rocky soil to reveal the black seam of coal below.

The coal goes directly to the power plant across the highway, where it’s pulverized and burned. This mine-to-mouth operation is the second-largest coal-fired power plant west of the Mississippi. But Murphy’s wife, Marti, says if you’re picturing blackened skies and sooty streets, you haven’t actually been to Colstrip.

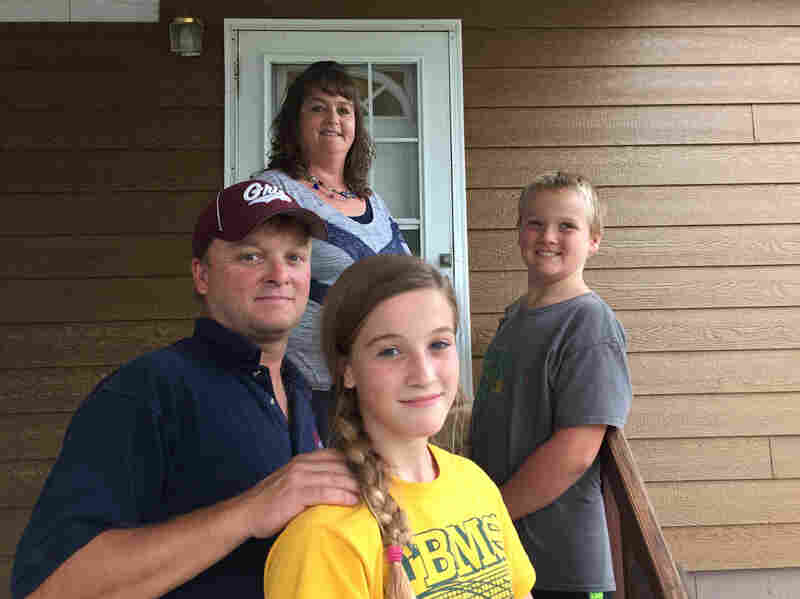

Marti and Kevin Murphy at home with their children Amy Martin/Montana Public Radio hide caption

itoggle caption Amy Martin/Montana Public Radio

How Montana Compares With Other States

“I feel like that is how we’re perceived, as a dirty coal mining town. It’s just not true,” she says.

Marti works in the accounts payable office at the mine. She points out the money generated from coal has given her community amenities you wouldn’t normally find in a town of just over 2,000 people.

“We have free golf if you live in the city limits, free gym membership if you live in the city limits, walking paths all around town, a park in every single neighborhood that you could think of,” she says.

The goal of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan is to reduce carbon emissions from the power sector by 30 percent nationwide from 2005 levels. Marti says she wants a healthy environment, but talk of shutting down coal-fired power plants feels threatening in Colstrip.

“It’s pretty scary because you think about it, and then you have to think, ‘Well, where would we go if something happened?’ ” she says.

Economist Mark Haggerty is with Headwaters Economics, an independent research group in Bozeman, Mont., that studies energy issues across the West.

“I would be worried,” he says.

Haggerty says the real threat to Colstrip may not be the Clean Power Plan. “There are larger market trends that are already forcing a big transition away from coal towards natural gas,” he says.

Those trends could be good for Montana. The state does produce some natural gas, and it’s also rich in renewable resources, like wind. The American Wind Energy Association ranks Montana third among states with potential land-based wind power generation. But it’s currently 21st in the nation for actual wind production. Haggerty says the infrastructure to move wind energy toward population centers is one of the primary things holding it back.

“Those issues I think will be resolved, and I would expect that we could see renewables being a significant competitor with both coal and natural gas over the next decade,” Haggerty says.

Jenni Bryce’s cattle graze around her family’s wind turbines and solar panels at her home near Belt, Mont. Amy Martin/Montana Public Radio hide caption

itoggle caption Amy Martin/Montana Public Radio

That transition is well underway for Jenni Bryce, who lives near the town of Belt, in central Montana. In the pasture behind her house, cattle are grazing, solar panels are collecting sunlight and several turbines are whirling in the wind.

“We have a Bergey 10-kilowatt wind turbine, which is probably the standard size for residential,” she says.

Bryce founded Pine Ridge Products 16 years ago. It’s a small-scale solar and wind installation company that she runs from her home. Bryce didn’t plan to become a renewable energy entrepreneur — she’s actually a speech therapist — but after she and her husband put up solar panels and a wind turbine for their own use, other families started asking them for advice. That led them to start consulting, manufacturing parts and designing new turbine models.

Climate change was not what motivated Bryce to start her business. She points out that families like hers have been using windmills for a long time.

“They’ve been using them for water pumping,” she says. “And you look back at our history of rural electrification and before that they used windmills connected to batteries for their power in their houses.”

In true Montana fashion, Bryce’s commitment to renewable energy grows out of her rural roots — and her passion for self-sufficiency. That passion will be needed to bring Montana into compliance with the new EPA rules and to help ease the transition away from coal in coming decades.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.