Elizabeth Warren’s Ambiguity On Health Care Comes With Some Side Effects

Sen. Elizabeth Warren speaks at the Presidential Candidate Forum on LGBTQ Issues last month in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Alex Wroblewski/Getty Images for GLAAD

hide caption

toggle caption

Alex Wroblewski/Getty Images for GLAAD

Sen. Elizabeth Warren has built a reputation as the presidential candidate with a plan for almost anything. Plans are her brand, so much so that her campaign shop sells T-shirts proclaiming “Warren has a plan for that.”

But the Massachusetts Democrat has not rolled out a health care plan of her own. Instead, she has insisted “I’m with Bernie on Medicare for All.” (Recently, after weeks of being hounded by both journalists and her opponents, Warren announced that in the next few weeks she’ll release a plan that outlines the costs for “Medicare for All” and how she intends to pay for it.)

Earlier in this campaign cycle, Warren referred to Medicare for All as a “framework” and seemed open to alternatives, telling CNN’s Jake Tapper that there could be a role for private insurance.

But Warren has also publicly tethered herself to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All plan, and on the debate stage this summer she raised her hand in support of eliminating private insurance.

In her academic work, Warren has long pointed to health insurance instability and high medical costs as a major cause of bankruptcy. In 2008, she co-authored a book chapter that referred to universal single-payer health care as “the most obvious solution.” But when that statement surfaced, and she was asked about single-payer during her 2012 Senate challenge to Scott Brown, she focused on cementing the then-newly passed Affordable Care Act.

Some voters and old colleagues are convinced that Warren is not as resolute on health care as Sanders, perhaps because of that historic willingness to aspire to a progressive goal, but be open to other options if the goal isn’t politically acceptable.

That flexibility might be a perception, but the frequency with which people bring it up is noteworthy.

“I think we need to improve Obamacare, have a public option, that’s the better way to go,” Donna Mombourquette said as she grabbed popcorn in between candidate speeches at the New Hampshire Democratic Party state convention last month.

Mombourquette, a New Hampshire state representative, said she considers Sanders too “far to the left,” particularly on health care. But Warren, who supports the same idea, is one of her top two choices.

“I guess with Elizabeth Warren, for some reason, I think that she’s probably gonna be more open to moderating her positions to bring in more voters,” said Mombourquette, who recently endorsed South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, but insists she still really likes Warren.

“That inconsistency is hurting”

While some of Warren’s fans might interpret her lack of health care details with their own positive spin, her opponents have not.

“Your signature, senator, is to have a plan for everything. Except this,” Buttigieg told Warren in the last Democratic debate as he pressed her over her refusal to concede that Medicare for All would require raising taxes on the middle class.

Public opinion polling has consistently shown that a public option, which would create a broad government-run insurance program like Medicare or Medicaid as an alternative to private insurance, is more popular than a mandatory Medicare for All system that would entirely eliminate the current employer-based insurance system.

Warren supports the less-popular health care option, and while that may be an uphill challenge politically, Chris Jennings, who served as a senior health care adviser to both Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, suggests the bigger challenge for Warren is that her lack of details on health care could undermine her brand.

“This is the one area where her lack of directness stands in contrast with all her other policy visions and message approaches” said Jennings. “To me, that inconsistency is hurting more than even the policy itself.”

Earlier this month, after weeks of sidestepping questions about health care, Warren said that she intends to release a plan soon that explains how she intends to pay for Medicare for All.

Warren speaks during a town hall event last month in Iowa City, Iowa.

Joshua Lott/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Joshua Lott/Getty Images

Whenever Warren has been asked about a potential tax increase to fund Medicare for All, she tries to reframe the question as a matter of costs, not taxes.

“This much I promise to you: I will not sign a bill into law that does not reduce the cost of health care for middle class families. That’s what matters to them, and that’s what matters to me,” she recently told voters at a town hall in Des Moines.

But as some in the ultra-left progressive flank of the party have begun to suggest that Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders is the only true believer in Medicare for All, Warren has also made a point to reaffirm her support for the idea itself.

“Medicare for All is the cheapest possible way to provide health care coverage for everyone,” she told voters in that same Des Moines speech. “I want you to hear it from me.”

“She will think clearly about alternatives”

Still, there is a sense among some people who like Warren that her support for Medicare for All is somewhat out of character.

“I was a little surprised recently that she came out in favor of a Medicare for All plan,” said Tom McGarity, who taught law school with Warren at the University of Texas in the early 1980s and is a fan of her candidacy. “My guess is as the campaign continues, she’ll refine that to some extent.”

“It’s a very expensive proposition, and it’s not well defined. One thing about Liz is, at least politically, usually before she comes out with something … she defines it better,” he added.

The Warren campaign has not responded to questions about whether she could eventually compromise on the issue.

It is not uncommon to meet die-hard Warren supporters who are lukewarm about Medicare for All.

Recent polling from NPR member station WBUR finds that Warren is the most popular candidate in her home state of Massachusetts, but her idea of Medicare for All is not. “Medicare for All Who Want It” is a more popular option.

“I’m not sure that Medicare for All is the correct answer. I think a hybrid is perhaps a better answer,” said Kimberly Winick, a former law school research assistant for Elizabeth Warren and a strong supporter of Warren’s candidacy.

“The real question isn’t whether you support every plank of the platform, but whether you think the person standing at the top is somebody whom you can trust,” she added.

Warren, seen speaking at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., last week, often ends her stump speech with a promise to “dream big” and “fight hard.”

Elise Amendola/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Elise Amendola/AP

And Winick trusts Warren. She worked closed with the senator in the 1980s on bankruptcy research and feels she has an understanding of her personality and work ethic.

“I also know down the road if it becomes implausible, impractical, impossible to do those things, she’ll consider alternatives,” she said. “And she will think clearly about alternatives, she won’t pretend facts don’t exist.”

Former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid espoused a similar thinking recently in a podcast interview with David Axelrod, a former strategist for President Obama. Reid, in an attempt to defend Warren from criticism that she’s “too far left,” gave the impression that Warren is not as committed to Medicare for All as she has suggested.

He said he advised Warren that strengthening Obamacare is the best plan for now, and a public option is “as good as Medicare for all, anyways.”

“That’s not what she’s saying though,” Axelrod responded.

“You give her some time,” Reid said. “I think she’s not in love with that, you’ll wait and see how that all turns out.”

“So you think she’s more pragmatic?” Axelrod asked.

“Oh, I know she’s pragmatic, just wait,” Reid insisted.

But pragmatism is not what Warren has been selling on the campaign trail. She often ends her stump speech with a promise to “dream big” and “fight hard.”

It’s not clear how much wiggle room — if any — Warren has on the substance of Medicare for All. But health care consultant Chris Jennings thinks she has a little bit more negotiating space than some of her rivals.

“Her fan base, her voters, will give her more credit for trying to go as far as she possibly can on this issue, and then when, and if, she has to trim it back a bit, she’ll have more room for compromise than many other candidates will,” said Jennings. “And I say that because she’s viewed as a fighter, she won’t compromise just to compromise, she’ll compromise to get something done.”

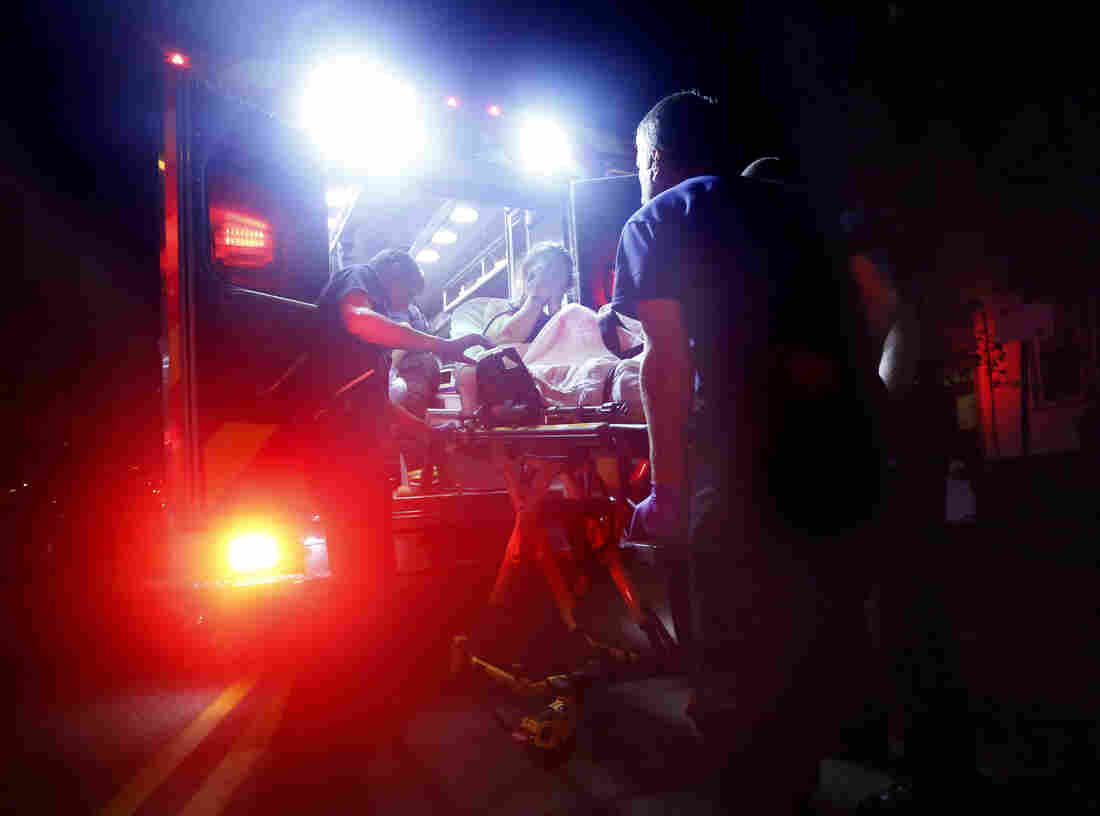

The Real Cost Of The Opioid Epidemic: An Estimated $179 Billion In Just One Year

Paramedics in Portland, Maine, respond to a call for a heroin overdose. A new report estimates some $60 billion was spent on health care related to opioid addiction in 2018.

Derek Davis/Portland Press Herald/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Derek Davis/Portland Press Herald/Getty Images

There’s a reckoning underway in the courts about the damage wrought by the opioid crisis and who should pay for it.

Thousands of cities and counties are suing drug makers and distributors in federal court. One tentative dollar amount floated earlier this week to settle with four of the companies: $48 billion. It sounds like a lot of money, but it doesn’t come close to accounting for the full cost of the epidemic, according to recent estimates — let alone what it might cost to fix it.

Of course, there’s a profound human toll that dollars and cents can’t capture. Almost 400,000 people have died since 1999 from overdoses related to prescription or illicit opioids. There are more deaths every single year than from traffic accidents. These are lives thrown into chaos, families torn apart — you can’t put a dollar figure on those things.

But the economic impact is important to understand. The most recent estimate of those costs comes from the Society of Actuaries and actuarial consulting firm Milliman in a report published this month.

“We pride ourselves that this is objective, nonpartisan research,” says Dale Hall, managing director of research at the Society of Actuaries. He adds, “we’re not here to influence any court proceedings.” As actuaries, they calculate financial numbers associated with risks, for instance, for insurance companies.

So how much did the epidemic cost in just one year, 2018? The total number they came to was $179 billion. And those are costs borne by all of society — both by governments providing taxpayer-funded services (estimated to be about a third of the cost), and also individuals, families, employers, private insurers, and more.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

When you start to break that number apart, a picture emerges of how opioid addiction ripples out into communities and across generations.

Overdose Deaths: $72.6 Billion

It makes sense that the biggest contributor to the costs of the epidemic comes from overdose deaths, according to Stoddard Davenport of Milliman, one of the report’s authors.

“When you think about the course of a person’s life that struggles with opioid use disorder, early mortality is the most significant adverse event that can happen, and I think that bears out when you look at the economic impact,” he says.

Every day, 130 people die from opioid overdoses. Most of them are in the 25-55 age range, right in the middle of their prime working years, and lost earning potential accounts for most of those costs.

“The mortality costs have a small component of end of life health care, coroner expenses and things like that,” he says. “The grand majority of it, however, is composed of lost lifetime earnings.”

Preliminary data suggests overdose deaths dipped in 2018 for the first time in years, but many experts say it’s too early to say if that marks a turnaround or not.

Hall points out whether the annual death toll stays as high as 47,000 in coming years “will be certainly a driver of what these overall economic costs will be.”

Health Care: $60.4 Billion

The next biggest amount comes from health care costs. The researchers took several large databases of insurance claims that had been scrambled to hide the identity of the patients and flagged people who’d been coded as having opioid use disorder. Then the researchers calculated their overall health care costs — not just directly related to their addiction, but any additional costs — and compared them to similar patients without addiction.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

“Looking at the difference in costs gives us a sense for how much more complicated is their overall health care picture and what are those additional expenses look like for two otherwise comparable people,” Davenport explains.

Opioid addiction is linked to other health problems. Patients might have chronic pain or mental illness that underlies their addiction; infectious diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C can spread among injection drug users; and there can also be higher costs for other conditions like anemia, liver disease, and pulmonary heart disease, according to another Milliman analysis from earlier this year.

An infant born dependent on opioiods receives care at a neonatal intensive care unit in Charleston, West Virginia. Costs associated with treating such infants reached close $1 billion in 2018.

Salwan Georges/The Washington Post/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Salwan Georges/The Washington Post/Getty Images

There are also health costs for people who live in the same household as someone with an opioid use disorder — their lives might be more complicated and their mental and physical health can suffer as a result.

Then there are the costs for infants born dependent on opioids — what’s called neonatal abstinence syndrome. “The epidemic effect is starting to create a second generation that extends down to children and unfortunately newborns as well,” Hall says. In 2018 those costs were $800 million, but they estimate this year they could be almost $1 billion.

There are still more costs the report could not capture, including elevated costs for patients whose opioid use disorder is undiagnosed, and potential ongoing expenses for children born with neonatal abstinence syndrome as they grow up.

Lost Productivity: $26.5 Billion

When someone is addicted to opioids, they might not be able to apply for or hold down a job, or they might be incarcerated and unable to work. The researchers broke this section out into reduced labor force participation, absenteeism, incarceration, short and long term disability, and workers’ compensation.

“What we’re trying to capture is the amount of time that folks are spending not doing economically productive activities,” Davenport says. Other productivity costs — like “presenteeism,” when someone shows up at work but isn’t as productive as they otherwise would be — were not included here.

It’s also worth noting, many of these costs fall to private employers, for instance, and families who have a family member not bringing home income.

“It’s around 30 percent falling on federal state and local governments,” he says. “The rest [falls to] the private sector and then of course to individuals.”

Criminal Justice: $10.9 Billion

Measuring this part of the costs of the epidemic is a different beast. The researchers captured costs related to police, court cases, correctional facilities and property lost to crime, Davenport explains. They drilled down into criminal justice expenses to see “what proportion of those total budgets involve substance use disorders, and then what proportion of that is represented by opioids.”

Having an opioid addiction dramatically increases the chance of being caught up in the criminal justice system. As NPR has reported, only 3% of the general population reported being recently arrested, on parole or on probation. For people with opioid use disorder, that jumped up to nearly 20%.

Child And Family Assistance & Education: $9 Billion

The team took a similar approach to calculate the costs for things like food assistance, child welfare, income and housing assistance, and education. They took those total costs, figured out what portion was related to substance use, and what part of that was related to opioid use.

The epidemic has a profound impact on families and communities — parents with opioid use disorder have to navigate treatment and sometimes battle for custody of their kids; the state has to handle child welfare cases and find new homes for foster kids; and schools are providing counseling for kids with addicted parents.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

“Typically an epidemic will start in one place but then it broadens out,” says Hall. “We’re starting to see a broadening out of the impact of the opioid epidemic into some second generation effects.”

Hall adds there are also “the costs of educating people about the epidemic and ways to prevent future opioid use disorder.” Those costs — mostly from federal grants for elementary and secondary education programs — came out to $1.2 billion last year.

What’s Missing: Turning The Crisis Around

These are some solid numbers that capture the current economic burden of the epidemic. Estimating what it’s going to cost to fix the crisis — to treat those who are addicted, to reduce overdose deaths, and more — is another story.

“The notion of abatement is that we want to deal with the problem that exists but also to begin to remedy it,” says Christopher Ruhm, professor of public policy and economics at the University of Virginia. He worked for several years on a 30-year abatement plan for Oklahoma as part of that state’s case against several drug companies.

For Oklahoma, Ruhm estimated treatment, prevention, education, surveillance for one year would cost $836 million. The judge in the case made his own calculations and ordered Johnson & Johnson to pay $572 million, though the amount has since been adjusted, and the case is currently being appealed.

If you scale Ruhm’s numbers up from that one state to the whole country, you get $69 billion to fund a year’s worth of abatement programs.

“I’m not saying that’s an appropriate calculation in the sense that things could be different in Oklahoma from other places,” Ruhm cautions. There are also costs that might come up on the federal level that wouldn’t be factored in for Oklahoma, such as research into effective addiction treatments.

Still, it gives you a rough idea, as society starts to take stock of what this epidemic is costing already, how much it will cost to try to fix it, and who should ultimately pay.

CDC Studying Tissue To Try And Track Down Root Cause Of Vaping-Related Lung Damage

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is starting to study lung tissue and chemicals from electronic cigarette vapor to track down the root cause of lung damage caused by vaping.

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Mysterious lung injuries have killed at least 33 e-cigarette users and sickened nearly 1,500. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is digging deeper to find the exact cause. NPR science correspondent Richard Harris traveled to Atlanta to learn about the latest twists in their investigation.

RICHARD HARRIS, BYLINE: The calming sound of a fountain echoes between two laboratories on the CDC’s Chamblee campus, but it’s fair to say that for many scientists working on vaping injuries at the federal health agency, the mood is not so serene. I’m told that in one of these laboratory buildings, they’ve actually started testing fluid that had been taken from the lungs of people who had been exposed to vaping products and ended up with severe lung disease. That’s a new step in the investigation, which has now swollen to include more than 140 CDC scientists and staff. The lab buildings are off-limits to most visitors, so on a visit Friday, I am guided instead into an adjoining building to meet the man who’s overseeing the labs.

Hey. Richard Harris.

JIM PIRKLE: Jim Pirkle. Nice to meet you.

HARRIS: Nice to meet you.

PIRKLE: Yeah. Come on in. Have a seat.

HARRIS: Dr. Pirkle has seen many investigations in his time. Best case, there’s a straight line from a health problem to the cause. Vaping lung disease, well, that’s a different story.

PIRKLE: There wasn’t something that just stood out in everything that closed the case and said, we know exactly what it is.

HARRIS: Pirkle realized early on that his labs, which started out studying the toxic chemicals in cigarettes, could be brought to bear for this mystery.

PIRKLE: We have 13 smoking machines, and we’re smoking cigarettes and e-cigarettes all the time – maybe not what you’re classically thinking CDC is doing.

HARRIS: Elsewhere, the Food and Drug Administration labs have been studying the vaping fluid from suspicious products, but people don’t just breathe that stuff in. E-cigarettes vaporize those components by heating them up.

PIRKLE: So after you’ve heated the fluid, it’s possible you’ve made something else that’s dangerous.

HARRIS: Pirkle shows me some components of the testing equipment.

PIRKLE: We have a pad here that’ll collect the aerosol and all the lipid-like substances, and then the stuff that goes through as gases – that is trapped on another trap. And so it’s just – it’s like a super filter right there.

HARRIS: Pirkle says they’ll compare what they find from the devices to what’s in the lungs of patients who fell ill. The first fluid samples from vapers’ lungs are just now being analyzed at the CDC.

PIRKLE: So that gives us kind of a sampling of what’s on the inside surface of the lung, and that’s actually very important because we think that’s where the problem is. It’s when things go in and get in contact with that inside surface of the lung.

HARRIS: One item on that list is to look for oils which have been observed in some samples. They’re also measuring natural compounds called terpenes that, among other things, contribute to the pungent flavor of THC extracted from marijuana – yes, terpenes as in turpentine. In all, they’re planning to run about a dozen tests on each vape and lung fluid sample, Pirkle says.

PIRKLE: It took a while to get all those methods developed, all that interpretation stuff figured out. But it started this morning, so we’re chugging on it. We’re out at 60 miles an hour.

HARRIS: Discoveries in this lab will get relayed back to Dr. Rom Koppaka, a lung specialist who got tapped to join the CDC’s vaping investigation team.

ROM KOPPAKA: From the beginning, the approach has been to entertain all potential theories.

HARRIS: And it’s often tricky to sort out cause and effect. For example, is oily material seen in some lung samples causing the problem or part of the body’s reaction? What about the signs of direct chemical damage in victim’s lungs? Koppaka is hoping the labs will provide answers. That can help guide treatment, but it is also urgently needed so doctors can know exactly what to look for to diagnose this condition.

KOPPAKA: We don’t have that yet. Certainly, if the cause or causes of the lung injury are identified, that would advance that effort a great deal because there might be a way to detect them in the lungs or in the blood or in the tissues or whatever. But we’re not there yet.

HARRIS: The consensus around the CDC team, though, is that they are heading in the right direction.

Richard Harris, NPR News.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Get Your Flu Shot Now, Doctors Advise, Especially If You’re Pregnant

Though complications from the flu can be deadly for people who are especially vulnerable, including pregnant women and their newborns, typically only about half of pregnant women get the needed vaccination, U.S. statistics show.

BSIP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

BSIP/Getty Images

October marks the start of a new flu season, with a rise in likely cases already showing up in Louisiana and other spots, federal statistics show.

The advice from federal health officials remains clear and consistent: Get the flu vaccine as soon as possible, especially if you’re pregnant or have asthma or another underlying condition that makes you more likely to catch a bad case.

Make no mistake: Complications from the flu are scary, says Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., who is part of a committee that advises federal health officials on immunization practices.

“As we get older, more of us get heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, asthma,” Schaffner says. “Those diseases predispose us to complications of flu — pneumonia, hospitalization or death. We need to make vaccination a routine part of chronic health management.”

Federal recommendations, he says, are that “anyone and everyone 6 months old and older in the United States should get vaccinated each and every year.” People 65 and above and pregnant women, along with patients who have underlying medical issues, should make haste to get that shot, if they haven’t already, Schaffner says.

Within a typical year, about two-thirds of people over 65 get vaccinated against the flu, studies show, compared with 45% of adults overall and 55% to 60% of children. But only about half of pregnant women get vaccinated, and immunization rates for people with chronic diseases hovers around 30% to 40%.

Take the case of JoJo O’Neal, a 55-year-old radio personality and music show host in Orlando, Fla., who was diagnosed with adult onset asthma in 2004 at age 40. For years she didn’t get the flu vaccine, figuring her healthful diet, intense exercise and overall fitness would be protective enough.

“I skated along for a lot of years,” O’Neal says, “and then, finally, in 2018 — boom! It hit me, and it hit me hard.” She was out of work for nearly two weeks and could barely move. She was extremely nauseated and had an excruciating headache and aching body, she says. “I spent a lot of time just sitting on my couch feeling miserable.”

O’Neal says it takes a lot to “shut her down,” but this bout with the flu certainly did. Even more upsetting, she says, she passed the virus on to her sister who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Fortunately, neither she nor her sister had to be hospitalized, but they certainly worried about it.

“We have lung issues and worry about breathing, so having the flu created lots of anxiety,” O’Neal says. This year, she’s not taking any chances: She has already gotten her flu shot.

That’s absolutely the right decision, says Dr. MeiLan Han, professor of internal medicine in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan Health System and a national spokesperson for the American Lung Association.

If generally healthy people contract the flu, they may feel sick for a week or more, she says. But for someone with underlying lung conditions, it can take longer to recover from the flu — three to four weeks. “What I worry about most with these patients,” Han says, “is hospitalization and respiratory failure.”

In fact, Han says, 92% of adults hospitalized for the flu have at least one underlying chronic condition such as diabetes, asthma, or kidney or liver disorders.

When people with underlying lung conditions contract the flu, she says, “the virus goes right to the lung, and it can make a situation where it’s hard to breathe even harder.”

Other chronic health conditions — diabetes, HIV and cancer, among them — impair the immune system, Han explains, making people with those conditions unable to mount a robust response to the flu virus without the immunization boost of a flu shot.

That means the inflammation and infection when they get the flu can become more severe, she says.

Even many of her own patients don’t realize how bad a case of the flu can be, Han says.

“People often tell me, ‘That’s not me. I’ve never had the flu. I’m not at risk, and I’m not around people who might give me the flu.’ “

O’Neal says she’d always figured she wasn’t at risk either — until the flu flattened her.

Healthy pregnant women, too, are more prone to complications and hospitalization if they contract the flu and are strongly urged by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and OB-GYNs to get vaccinated against both influenza and pertussis. Yet the majority of mothers-to-be surveyed in the United States — 65% — have not been immunized against those two illnesses, according to a recent CDC Vital Signs report.

Some women mistakenly worry that the flu vaccine isn’t safe for them or their babies. “I think some of the fears about safety are certainly understandable, but they’re misinformed,” says Dr. Alicia Fry, chief of the epidemiology and prevention branch of the CDC’s Influenza Division.

The evidence is clear, Fry says: The vaccine is extremely safe. And she points to a recent study showing that immunization against flu reduces the risk of flu hospitalization among pregnant women by 40%.

As for worries that the woman’s vaccination might not be safe for her developing fetus, Fry says the opposite is true. When a pregnant woman is immunized, antibodies that fight the flu virus cross the placenta and can protect her baby in those critical months before and after birth.

“It can prevent 70% of the illness associated with flu viruses in the baby,” Fry says. “So it’s a double protection: Mom is protected, and the baby’s protected.” Infants can’t get the flu vaccine themselves until they are 6 months old.

Now, the vaccine won’t protect against all strains of the flu virus that may be circulating. But Schaffner says the shot is still very much worth getting this year and every year.

“Although it’s not perfect, the vaccine we have today actually prevents a lot of disease completely,” he says. “And even if you do get the flu, it’s likely to be less severe, and you’ll be less likely to develop complications.”

PHOTOS: Why Lynsey Addario Has Spent 10 Years Covering Maternal Mortality

Addario’s coverage of maternal mortality took her to a remote village in Badakhshan province, Afghanistan in 2009, where she photographed a midwife giving a prenatal check in a private home. “In these areas someone will announce that a doctor and a midwife are coming, and any pregnant and lactating women within a certain radius come if they want prenatal or postnatal care,” she says.

Lynsey Addario

hide caption

toggle caption

Lynsey Addario

Editor’s note: This story includes images that some readers may find disturbing.

When photojournalist Lynsey Addario was awarded the MacArthur Fellowship in 2009, she took it as a chance to work on a topic that many photographers and editors shied away from: maternal mortality. Her photos of overcrowded hospitals, bloody delivery room floors and midwives in training illustrate the challenges women face in childbirth and what the global health community is doing to overcome it. The series was featured at this year’s Visa Pour L’image festival in Perpignan, France.

Addario has borne witness to some of the most intense global conflicts of her time. She has worked for publications like The New York Times, National Geographic and Time Magazine and has covered life under the Taliban in Afghanistan and the plight of Syrian refugees. She has been kidnapped twice while on assignment, most recently in Libya in 2011 while covering the civil war.

Every two minutes, a woman dies from childbirth or pregnancy-related causes, and many of these deaths are entirely preventable. While the global health community has made great strides bringing down the rate of these maternal mortalities since efforts intensified in the early 1990s, the reality for many mothers is still harrowing.

We spoke to Addario, author of the 2015 memoir It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War, about what drives her work and what she’s witnessed over a decade of reporting on this topic. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Addario recalls visiting Tezpur Civil Hospital in Assam, India, “where there’s tea plantations all around. In that area I was looking at the conditions for women, and you can tell that [the hospital] is grossly overcrowded. There were women waiting to deliver, some had already delivered — there were even women sleeping in the hallways of this hospital on the stairs leading up to the main ward.”

Lynsey Addario

hide caption

toggle caption

Lynsey Addario

How did you get interested in the topic of maternal mortality?

In 2009 I was named a MacArthur Fellow. It was the first time in my career where I was given money to work on a project without an assignment, so I could choose something that I felt was important to cover. I started learning about the incredible number of women who were dying in childbirth every year. It wasn’t a story that was easy to get published — I think most editors felt it wasn’t a sexy topic. Most people just don’t realize what a big deal this is.

[Early in the project,] in the very first hospital I walked into outside of Freetown, Sierra Leone, I literally watched a very young woman, Mamma Sessay, hemorrhage in front of me on camera and die. And I knew that it was a story I had to continue with.

You write in your book Of Love & War that what compels you to do photojournalism is “documenting injustice.” How does that apply in this series?

If you’re a poor woman living in a village where there are no medical professionals around, and you don’t have enough money to get to a hospital, then you run the risk of dying in childbirth. That’s injustice. I think everyone is entitled to a safe delivery. In 2019 there should be medical facilities within reach for anyone to be able to access them, or mobile clinics.

“This is a fistula repair in Kabul, Afghanistan, with two surgeries going on side by side,” Addario says. “A fistula is a tear, often between the vagina and the anus. It’s common in many countries with child marriage, or where women have birth very young. It’s quite a shame — often women are shunned from their houses or don’t get care — there’s often a smell associated with fistula.”

Lynsey Addario

hide caption

toggle caption

Lynsey Addario

Were you a mother when you started the project?

No. In fact I always used to joke around on the delivery ward that I would never become a mother because I had photographed so many women delivering, and I knew it was such a painful and difficult experience. Then in 2011 I gave birth to my first son, so I ended up doing it anyway. Even though this project made me more scared to actually deliver because I know how many things can go wrong.

Ironically my own delivery in 2011 was not a great experience. I moved to London when I was 32 weeks pregnant and delivered at 37 weeks. I had no doctor, basically just showed up at the hospital nine centimeters dilated and delivered with whatever midwife was on duty. Now that I’ve been doing this project for 10 years, there are so many things I would suggest to first-time mothers — or second-time mothers.

Like what?

Like maybe have a doula or have someone with you who can be an advocate — who can explain to you what’s going on with your body, who can help you navigate the pain. Someone who can understand if something’s going wrong, like the symptoms of preeclampsia: headaches, sweating, swelling. There’s so much that we just don’t know, that we’re not taught. People take childbirth for granted.

What is it like talking to your male colleagues about this project?

Most of them just haven’t paid attention to this work. Colleagues have said things to me about some stories — like the woman giving birth on the side of the road in the Philippines and the Mamma Sessay story — because they’re sensational, but no one really asked me about the work, which is interesting in and of itself. I think people sort of shy away from talking about birth, you know? Unless it’s something happy and positive.

“This is part of Dr. Edna Ismail’s team doing outreach in a remote village in Somaliland,” Addario says. “They do a similar thing like in Afghanistan, where they make an announcement for any pregnant and lactating women to come for a prenatal check. That’s essentially the only way women can get care unless they walk or are able to get transport to the nearest hospital or clinic.”

Lynsey Addario

hide caption

toggle caption

Lynsey Addario

What has surprised you while photographing this series?

How much access people give me. I’ve photographed — I can’t even count how many — probably three or four dozen births. The women invite me into very intimate spaces. I obviously try to be very respectful of how I photograph something like this. It’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever witnessed, watching a baby be born. It’s something delicate to photograph because it’s so incredible and at the same time it’s very graphic. It’s hard, and it’s always surprising to me how many people have let me in.

That word “graphic” jumps out at me. I’m looking at one of your photos now, where there’s blood on a delivery room floor, and it’s uncomfortable in a way that’s different than looking at blood from violence.

A mother receives postnatal care in a Somaliland hospital. “She was brought [there] in a wheelbarrow,” Addario recalls. “She delivered her baby stillborn then started hemorrhaging. It was extraordinary for me to witness — it was very similar to what I’d seen a decade earlier when Mamma Sessay died but in this case the woman survived because there were trained midwives who knew exactly what to do.”

Lynsey Addario

hide caption

toggle caption

Lynsey Addario

It is different. It’s different because no one thinks of childbirth like that. They think of childbirth as Hallmark pictures, but there’s a lot that’s not beautiful about it.

You’ve been working on this project for 10 years now. What has changed?

The statistics [for maternal mortality] have gone down, which is incredible, and there’s a lot more awareness. There are so many organizations — like Every Mother Counts, which is Christy Turlington’s organization, and UNFPA and UNICEF — working to fight maternal death. There’s more information, but it’s still too many — one woman a day is too many.

Opioid Case With 2 Ohio Counties As Plaintiffs Set To Go To Trial Next Week

The first federal case against the opioid industry goes to trial Monday. Some companies have settled to avoid trial, others will get their day in court.

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Local governments across the country want the drug industry to pay for the damage from the opioid crisis. Thousands of counties, cities, Native American tribes and other parties have sued manufacturers, distributors and pharmacies. Opening arguments are scheduled to begin next Monday in the first set of claims to go to trial. Two Ohio counties will serve as plaintiffs. And all the while, attorneys continue to negotiate possible settlements. From member station WCPN, Nick Castele reports.

NICK CASTELE, BYLINE: Eric Stimac’s path to addiction began with a work injury. Several years ago, he says, he was working a side job on a day off.

ERIC STIMAC: It was some stage flooring. We were unloading off of the back of a box truck. And it fell off of the lift gate and then landed on my foot and crushed my foot.

CASTELE: Stimac was prescribed opioid painkillers, he says, and grew addicted. After a close friend died of a heroin overdose, Stimac describes reacting in a way that may seem surprising.

STIMAC: My first thought was, well, if, you know, if this was something that they were willing to give their life over, what’s the deal with it, you know? So that’s when I tried heroin for the first time.

CASTELE: After an arrest, Stimac sought treatment at IBH Addiction Recovery Center, where we talked on a porch overlooking the campus. It’s a residential facility in Summit County, Ohio, one of the two plaintiffs in the upcoming trial. Stimac is now part of a post-treatment volunteer program that he says has given meaning to his life.

Many people have gone down the same road, beginning with prescription pills before moving to street drugs, such as heroin or fentanyl. That’s why counties say drug companies are responsible for lighting the fuse of an addiction crisis that exploded and strained local services.

JONATHAN WYLLY: An average episode here is going to cost between $15-20,000.

CASTELE: Jonathan Wylly is the executive director of IBH. Treatment centers like this one often bill Medicaid for those costs, he says, and also receive funding from county addiction and mental health boards. Wylly says no amount of money can truly match the damage that people have suffered here.

WYLLY: There’s no number they can come up with that’s going to meet at the societal cost of what the opiate epidemic has meant to this state.

CASTELE: There’s the cost to medical examiners for toxicology reports after overdose deaths, to the foster system to care for children who have lost parents, to local jails and courts that handle drug cases. An expert witness for the plaintiffs says damages in these two Ohio counties could run higher than $200 million. The counties have accused drug companies of marketing painkillers aggressively while underplaying the risk of addiction and of failing to control suspicious orders of pills.

ANDREW POLLIS: This case, the facts of the case are just incredibly strong. They’re devastating.

CASTELE: Andrew Pollis is a law professor at Case Western Reserve University.

POLLIS: They demonstrate, really, a profit-driven desire to exploit the fact that opioids are inherently physically addictive.

CASTELE: Companies didn’t make representatives available for interviews. But in court filings, they’ve said counties can’t pin the crisis on the industry. They say they plan to argue that they complied with a changing set of federal rules and that they can’t be blamed for the damage of illegal drugs. Abbe Gluck is faculty director of the Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy at Yale Law School.

ABBE GLUCK: I would predict that we’re going to see a lot of attention to this question of causation. Can we really say that all of these different defendants caused the harm that they’re being sued for causing?

CASTELE: She says defendants may point out there are many decision-makers in the drug supply chain, including the FDA, doctors and patients.

GLUCK: And what the defendants have been saying all along is that it’s impossible to trace any one of their actions to any one overdose or any one addiction problem.

CASTELE: Manufacturers have largely settled with the two Ohio counties, allowing them to avoid trial. And settlement negotiations have gone down to the wire with opioid distributors. Those possible nationwide agreements could be worth billions of dollars.

For NPR News, I’m Nick Castele in Cleveland.

(SOUNDBITE OF WIDOWSPEAK SONG, “NARROWS”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Hospital Giant Sutter Health Agrees To Settlement In Big Antitrust Fight

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, along with 1,500 self-funded health plans, sued Sutter Health for antitrust violations. The closely watched case, which many expected to set precedents nationwide, ended in a settlement Wednesday. Above, Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif.

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Rich Pedroncelli/AP

Sutter Health, a large nonprofit health care system with 24 hospitals, 34 surgery centers and 5,500 physicians across Northern California, has reached a preliminary settlement agreement in a closely watched antitrust case brought by self-funded employers and later joined by California’s Office of the Attorney General.

The agreement was announced in San Francisco Superior Court on Wednesday, just before opening arguments were expected to begin.

Details have not been made public, and the parties declined to talk to reporters. Superior Court Judge Anne-Christine Massullo told the jury that details likely will be made public during approval hearings in February or March.

There were audible cheers from the jury following the announcement that the trial, which was expected to last for three months, would not continue.

Sutter, which is based in Sacramento, Calif., stood accused of violating California’s antitrust laws by using its market power to illegally drive up prices.

Health care costs in Northern California, where Sutter is dominant, are 20% to 30% higher than in Southern California, even after adjusting for cost of living, according to a 2018 study from the Nicholas C. Petris Center at the University of California, Berkeley, that was cited in the complaint.

The case was a massive undertaking, representing years of work and millions of pages of documents, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra said before the trial. Sutter was expected to face damages of up to $2.7 billion.

Sutter Health consistently denied the allegations and argued that it used its market power to improve care for patients and expand access to people in rural areas. The chain of health care facilities had $13 billion in operating revenue in 2018.

The case was expected to have nationwide implications on how hospital systems negotiate prices with insurers. It is not yet clear what effect, if any, a settlement agreement would have on Sutter’s tactics or those of other large systems.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Trump Is Trying Hard To Thwart Obamacare. How’s That Going?

President Trump talked to seniors about health care in central Florida in early October. “We eliminated Obamacare’s horrible, horrible, very expensive and very unfair, unpopular individual mandate,” Trump told the crowd.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images

The very day President Trump was sworn in — Jan. 20, 2017 — he signed an executive order instructing administration officials “to waive, defer, grant exemptions from, or delay” implementing parts of the Affordable Care Act, while Congress got ready to repeal and replace Barack Obama’s signature health law.

Months later, repeal and replace didn’t work, after the late Arizona Sen. John McCain’s dramatic thumbs down on a crucial vote (Trump still frequently mentions this moment in his speeches and rallies, including in his recent speech on Medicare).

After that, the president and his administration shifted to a piecemeal approach, as they tried to take apart the ACA. “ObamaCare is a broken mess,” the president tweeted in the fall of 2017, after repeal in Congress had failed. “Piece by piece, we will now begin the process of giving America the great HealthCare it deserves!”

Two years later, what has his administration done to change the ACA, and who’s been affected? Below are five of the biggest changes to the federal health law under President Trump.

1. Individual mandate eliminated

What is it? The individual mandate is the requirement that all U.S. residents either have health insurance or pay a penalty. The mandate was intended to help keep the premiums for ACA policies low by ensuring that more healthy people entered the health insurance market.

What changed? The 2017 Republican-backed tax overhaul legislation reduced the penalty for not having insurance to zero.

What does the administration say? “We eliminated Obamacare’s horrible, horrible, very expensive and very unfair, unpopular individual mandate. A total disaster. That was a big penalty. That was a big thing. Where you paid a lot of money for the privilege […] of having no healthcare.” — President Trump, The Villages, Florida, Oct. 3, 2019

What’s the impact? First of all, getting rid of the penalty for skipping insurance opened a new avenue of attack against the entire ACA in the courts, via the Texas v. Azar lawsuit. Back in 2012, the ACA had been upheld as constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, because the penalty was essentially a tax, and Congress is allowed to create a new tax. Last December, though, a federal judge in Texas ruled that now that the penalty is zero dollars, it’s a command, not a tax, and is therefore unconstitutional. He also reasoned that it cannot be cut off from the rest of the law, so he judged the whole law to be unconstitutional. A decision from the appeals court is expected any day now.

Eliminating the penalty also caused insurance premiums to rise, says Sabrina Corlette, director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University. “Insurance companies were getting very strong signals from the Trump administration that even if the ACA wasn’t repealed, the Trump administration probably was not going to enforce the individual mandate,” she says. Insurance companies figured that without a financial penalty, healthy people would opt not to buy insurance, and the pool of those that remained would be smaller and sicker.

So, even though the zero-dollar-penalty didn’t actually go into effect until 2019, Corlette says, “insurance companies — in anticipation of the individual mandate going away and in anticipation that consumers would believe that the individual mandate was no longer going to be enforced — priced for that for 2018.” According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, premiums went up about 32%, on average, for ACA “silver plans” that went into effect in early 2018, although most people received subsidies to off-set those premium hikes.

2. States allowed to add “work requirements” to Medicaid

What is it? Medicaid expansion was a key part of the ACA. The federal government helped pay for states (that chose to) to expand Medicaid eligibility beyond families to include all low-income adults; and to raise the income threshold, so that more people would be eligible. So far, 37 states and D.C. have opted to expand Medicaid.

What changed? Under Trump, if they get approval from the federal government, states can now require Medicaid beneficiaries to prove with documentation that they either work or go to school.

What does the administration say? “When you consider that, less than five years ago, Medicaid was expanded to nearly 15 million new working-age adults, it’s fair that states want to add community engagement requirements for those with the ability to meet them. It’s easier to give someone a card; it’s much harder to build a ladder to help people climb their way out of poverty. But even though it is harder, it’s the right thing to do.” — Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Washington, D.C., Sept. 27, 2018

What’s the impact? Even though HealthCare.gov and the state insurance exchanges get a lot of attention, the majority of people who gained health care coverage after the passage of the ACA — 12.7 million people — actually got their coverage by being newly able to enroll in Medicaid.

Medicaid expansion has proven to be quite popular. And in the 2018 election, three more red states — Idaho, Nebaska, and Utah — voted to join in. Right now, 18 states have applied to the federal government to implement work requirements; but most such programs haven’t yet gone into effect.

“The one work requirement program that’s actually gone into effect is in Arkansas,” says Nicholas Bagley, professor of law at the University of Michigan and a close follower of the ACA. “We now have good data indicating that tens of thousands of people were kicked off of Medicaid, not because they were ineligible under the work requirement program, but because they had trouble actually following through on the reporting requirements — dealing with websites, trying to figure out how to report hours effectively, and all the rest.”

If more states are able to implement work requirements, Bagley says, that could lead “to the loss of coverage for tens of thousands — or even hundreds of thousands — of people.”

CMS administrator Verma has pushed back on the idea that these requirements are “some subversive attempt to just kick people off of Medicaid.” Instead, she says, “their aim is to put beneficiaries in control with the right incentives to live healthier, independent lives.”

Work requirements in Arkansas and Kentucky were put on hold by a federal judge in March, and those cases are on appeal. The issue is likely headed to the Supreme Court.

3. Cost-sharing reduction subsidies to insurers have ended.

What is it? Payments from the federal government to insurers to motivate them to stay in the ACA insurance exchanges and help keep premiums down.

What changed? The Trump administration suddenly stopped paying these subsides in 2017.

What does the administration say? “I knocked out the hundreds of millions of dollars a month being paid back to the insurance companies by politicians. […] This is money that goes to the insurance companies to line their pockets, to raise up their stock prices. And they’ve had a record run. They’ve had an incredible run, and it’s not appropriate.” — President Trump, the White House, Oct 17, 2017

What’s the impact? This change had a strange and unexpected impact on the new insurance markets set up by the ACA. Insurers were in a bind: They had to offer subsidies to low-income people applying for insurance, but the federal government was no longer reimbursing them.

“The first thinking [was], ‘Oh gosh, that’s going to cause premiums to go up, and it’s going to hurt the marketplace,’ ” says Christine Eibner, who tracks the ACA at the nonpartisan RAND corporation. “What ended up happening is, insurers, by and large, addressed this by increasing the price of the silver plan on the health insurance exchanges.”

This pricing strategy was nicknamed “silver loading.” Because the silver plan is the one used to calculate tax credits, the Trump administration still ended up paying to subsidize people’s premiums, but in a different way. In fact, “it has probably led to an increase in federal spending” to help people afford marketplace premiums, Eibner says.

“Where the real damage has been done is for folks who aren’t eligible for subsidies — who are making just a little bit too much for those subsidies,” adds Corlette. “They really are priced out of comprehensive ACA-compliant insurance.”

4. Access to short-term “skinny” plans has been expanded

What is it? The ACA initially established rules that health plans sold on HealthCare.gov and state exchanges had to cover people with pre-existing conditions and had to provide certain “essential benefits.” President Obama limited any short-term insurance policies that did not provide those benefits to a maximum duration of three months. (The original idea of these policies is that they can serve as a helpful bridge for people between school and a job, for example.)

What changed? The Trump administration issued a rule last year that allowed these short-term plans to last 364 days and to be renewable for three years.

What does the administration say? “We took swift action to open short-term health plans and association health plans to millions and millions of Americans. Many of these options are already reducing the cost of health insurance premiums by up to 60% and, really, more than that.” President Trump, The White House, June 14, 2019

What’s the impact? The new rule went into effect last October, though availability of these short-term or “skinny” plans varies depending on where you live — some states have passed their own laws that either limit or expand access to them. Some federal actuaries projected lots of people would leave ACA marketplaces to get these cheaper plans; they said that would likely increase the size of premiums paid by people who buy more comprehensive coverage on the ACA exchanges. But a recent analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation finds that the ACA marketplaces have actually stayed pretty stable.

Still, there’s another consequence of expanding access to these less comprehensive plans: “People who get these “skinny” plans aren’t really fully protected in the event that they have a serious health condition and need to use their insurance,” Eibner says. “They may find that it doesn’t cover everything that they would have been covered for, under an ACA-compliant plan.”

For instance, you might pay only $70 a month in premiums, but have a deductible that’s $12,500 — so if you get really sick or get into an accident, you could be in serious financial straits.

5. Funds to facilitate HealthCare.gov sign-ups slashed.

What is it? The ACA created Navigator programs and an advertising budget to help people figure out specifics of the new federally run insurance exchanges and sign up for coverage.

What changed? In August 2017, the administration significantly cut federal funding for these programs.

What does the administration say? “It’s time for the Navigator program to evolve […] This decision reflects CMS’ commitment to put federal dollars for the federally facilitated Exchanges to their most cost effective use in order to better support consumers through the enrollment process.” — CMS Administrator Seema Verma, written statement, July 10, 2018

What’s the impact? It’s hard to document what the impact of this particular cut was on enrollment. The cuts were uneven, and some states and cities got creative to keep providing services. “We have seen erosion in overall health insurance coverage,” says Corlette. “But it’s hard to know whether that’s the effect of the individual mandate going away, the short term plans or the reductions in marketing and outreach — it’s really hard to tease out the impact of those three changes.”

Overall, Nicholas Bagley says, the ACA has been “pretty resilient to everything, so far, that the Trump administration has thrown at it.” Some of Trump’s efforts to hobble the law have been caught up in the courts; others have not gone into effect. And, despite efforts to lure people away from the individual insurance marketplaces or to make ACA policies unaffordable, “the marketplaces have proved themselves to be remarkably resilient,” Corlette says.

Abbe Gluck, director of the Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy at Yale, cautions that though the law has proven to be stronger than expected, all these actions by the Trump administration have, indeed, had an effect.

“These actions have been designed to depress enrollment — they have depressed enrollment,” she says. “They have increased insurance prices.” Also, the uninsurance rate for U.S. residents also went up in 2018 for the first time since before the ACA was passed.

Despite that, one of the things that have kept the marketplaces as strong as they are, Gluck notes, is that they’re not all run by the federal government.

“Since the Affordable Care Act is implemented half by state governments — mostly blue states — those state governments have been able to resist these sabotaging efforts,” Gluck says.

“They have been able to extend enrollment, and they have been able to do outreach, because they run their own insurance markets. And in those states there is already evidence that sabotage attacks have not been felt as strongly.”

The piecemeal attacks on the ACA have made many people nervous about the future of their health coverage, Gluck says. “The most important theme of [Trump’s] administration of the ACA has been to sow uncertainty into the market and destabilize the insurance pool,” she says.

With open enrollment for 2020 health plans set to kick off in just a few weeks, Bagley wants people to know the ACA is still strong.

The federal health law “has been battered,” Bagley says. “It has been bruised. But it is still very much alive.”

Heads Up: A Ruling On The Latest Challenge To The Affordable Care Act Is Coming

The latest challenge to the Affordable Care Act, Texas v. Azar, was argued in July in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. Attorney Robert Henneke, representing the plaintiffs, spoke outside the courthouse on July 9.

Gerald Herbert/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Gerald Herbert/AP

A decision in the latest court case to threaten the future of the Affordable Care Act could come as soon as this month. The ruling will come from the panel of judges in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which heard oral arguments in the Texas v. Azar lawsuit.

An estimated 24 million people get their health coverage through programs created under the law, which has faced countless court challenges since it passed.

In court in July, only two of the three judges — both appointed by Republican presidents — asked questions. “Oral argument in front of the circuit went about as badly for the defenders of the Affordable Care Act as it could have gone,” says Nicholas Bagley, a professor of law at the University of Michigan. “To the extent that oral argument offers an insight into how judges are thinking about the case, I think we should be prepared for the worst — the invalidation of all or a significant part of the Affordable Care Act.”

Important caveat: Regardless of this ruling, the Affordable Care Act is still the law of the land. Whatever the 5th Circuit rules, it will be a long time before anything actually changes. Still, the timing of the ruling matters, says Sabrina Corlette, director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University.

“If that decision comes out before or during open enrollment, it could lead to a lot of consumer confusion about the security of their coverage and may actually discourage people from enrolling, which I think would be a bad thing,” she says.

Don’t be confused. Open enrollment begins Nov. 1 and runs at least through Dec. 15, and the insurance marketplaces set up by the law aren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

That’s not to underplay the stakes here. Down the line, sometime next year, if the Supreme Court ends up taking the case and ruling the ACA unconstitutional, “the chaos that would ensue is almost possible impossible to wrap your brain around,” Corlette says. “The marketplaces would just simply disappear and millions of people would become uninsured overnight, probably leaving hospitals and doctors with millions and millions of dollars in unpaid medical bills. Medicaid expansion would disappear overnight.

“I don’t see any sector of our health care economy being untouched or unaffected,” she adds.

So what is this case that — yet again — threatens the Affordable Care Act’s very existence?

A quick refresher: When the Republican-led Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, it zeroed out the Affordable Care Act’s penalty for people who did not have health insurance. That penalty was a key part of the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the law in 2012, so after the change to the penalty, the ACA’s opponents decided to challenge it anew.

Significantly, the Trump administration decided in June not to defend the ACA in this case. “It’s extremely rare for an administration not to defend the constitutionality of an existing law,” says Abbe Gluck, a law professor and the director of the Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy at Yale University. “The administration is not defending any of it — that’s a really big deal.”

The basic argument made by the state of Texas and the other plaintiffs? The zero dollar fine now outlined in the ACA is a “naked, penalty-free command to buy insurance,” says Bagley.

Here’s how the argument goes, as Bagley explains it: “We know from the Supreme Court’s first decision on the individual mandate case that Congress doesn’t have the power to adopt a freestanding mandate, it just has the power to impose a tax.” So therefore, the argument is that “the naked mandate that remains in the Affordable Care Act must be unconstitutional.”

The case made by the plaintiffs goes further, asserting that because the individual mandate was described by the Congress that enacted it as essential to the functioning of the law, this unconstitutional command cannot be cut off from the rest of the law. If the zero dollar penalty is unconstitutional, the whole law must fall.

Last December, a federal judge in Texas agreed with that entire argument. His judgement was appealed to the panel of judges in the 5th Circuit. Even if those judges agree that the whole law is unconstitutional, that would not be the end of the story — the case will almost certainly end up before the Supreme Court. It would be the third case to challenge the Affordable Care Act in the nation’s highest court.

So if the ruling will be appealed anyway, does it matter? “It matters for at least two reasons,” Bagley says. “First of all, if the 5th Circuit rejects the lower court holding and decides that the whole law is, in fact, perfectly constitutional, I think there’s a good chance the Supreme Court would sit this one out.”

On the other hand, if the 5th Circuit invalidates the law, it almost certainly will go the Supreme Court, “which will take a fresh look at the legal question,” he says. Even if the Supreme Court ultimately decides whether the ACA stands, “you never want to discount the role that lower court decisions can play over the lifespan of a case,” Bagley says.

The law has been dogged by legal challenges and repeal attempts from the very beginning, and experts have warned many times about the dire consequences of the law suddenly going away. Nine years in, “the Affordable Care Act is now part of the plumbing of our nation’s health care system,” Bagley says. “Ripping it out would cause untold damage and would create a whole lot of uncertainty.”

Canada’s Decision To Make Public More Clinical Trial Data Puts Pressure On FDA

Already, Health Canada has posted safety and efficacy data online for four newly approved drugs; it plans to release reports for another 13 drugs and three medical devices approved or rejected since March.

Teerapat Seedafong/EyeEm/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Teerapat Seedafong/EyeEm/Getty Images

Last March, Canada’s department of health changed the way it handles the huge amount of data that companies submit when seeking approval for a new drug, biological treatment, or medical device — or a new use for an existing one. For the first time, Health Canada is making large chunks of this information publicly available after it approves or rejects applications.

Within 120 days of a decision, Health Canada will post clinical study reports on a new government online portal, starting with drugs that contain novel active ingredients and adding devices and other drugs over a four-year phase-in period. These company-generated documents, often running more than 1,000 pages, summarize the methods, goals, and results of clinical trials, which test the safety and efficacy of promising medical interventions. The reports play an important role in helping regulators make their decisions, along with other information, such as raw data about individual patients in clinical trials.

So far, Health Canada has posted reports for four newly approved drugs — one to treat plaque psoriasis in adults, two to treat two different types of skin cancer, and the fourth for advanced hormone-related breast cancer — and is preparing to release reports for another 13 drugs and three medical devices approved or rejected since March.

Canada’s move follows a similar policy enacted four years ago by the European Medicines Agency of the European Union. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, on the other hand, continues to treat this information as confidential to companies and rarely makes it public.

The argument for more transparency

Transparency advocates say clinical study reports need to be made public in order to understand how regulators make decisions and to independently assess the safety and efficacy of a drug or device. They also say the reports provide medical societies with more thorough data to establish guidelines for a treatment’s use, and to determine whether articles about clinical trials published in medical journals — a key source of information for clinicians and medical societies — are accurate.

“Sometimes regulators miss things that have been hidden in those clinical study reports,” says Matthew Herder, director of the Health Law Institute at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. “Regulators often face resource constraints, they have deadlines, other priorities.”

Last year, for example, Canadian researchers used a clinical study report and other previously non-public information from a clinical trial to call into question the efficacy of Diclectin (known as Diclegis in the United States), a commonly prescribed drug to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. The team had requested the information from Health Canada under an older policy, which required researchers to sign a confidentiality agreement and keep the underlying data secret when they published their results. (It “had a chilling effect,” Herder says of the now-discontinued policy, and not many researchers made requests.)

Duchesnay, the Quebec-based manufacturer of Diclectin, defended the drug, and the Canadian and American professional societies of obstetricians and gynecologists continue to recommend it. Yet the new analysis gave pause to the College of Family Physicians of Canada, which had previously published two articles recommending Diclectin’s use in its medical journal, Canadian Family Physician. The organization took the unusual step in January of publishing a correction, which criticized the independence and accuracy of the two earlier articles. And, citing the new research, it advised physicians to use caution when interpreting recommendations for the drug’s use.

Herder and other lawyers and independent researchers who want to see greater transparency in medical research are urging the FDA to follow the example of Canada and the E.U., but without success thus far. To date, the European program, which has been in effect since 2016, has posted clinical study reports for 132 medicinal products whose applications were submitted after January 2015.

Canadian and European regulators lead the way

It is important to have multiple regulators making the data public, says Peter Doshi, an associate editor at the BMJ, an international medical journal, and an associate professor of pharmaceutical health services research at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy. As it stands now, “If FDA approves first, which often it does, we won’t know anything until Health Canada or the EMA makes a decision,” says Doshi. “And not every drug, device, biologic out there is going to be approved by these other regulators or even submitted to these other markets.”

In addition, redundancy lessens the impact if one regulator changes policy. The EMA, for example, earlier this year moved its operations from London to Amsterdam because of Britain’s anticipated exit from the European Union. Clinical data publication “was one of the activities suspended until we are more settled in Amsterdam,” says Anne-Sophie Henry-Eude, head of documents access and clinical data publication. No date has yet been announced for its resumption.

Sandy Walsh, a spokesperson for the FDA, says the agency does not have the same freedom as Canadian and European regulators to release clinical study reports. “U.S. laws on disclosure of trade secret, confidential commercial information, and personal privacy information differ from those governing EMA and Health Canada’s disclosure of clinical study reports,” she wrote in an email.

Some legal experts argue the FDA has more flexibility than it acknowledges. Federal agencies are “entitled to substantial deference” in determining “what constitutes confidential commercial information,” Amy Kapczynski, a Yale law professor and a co-director of the university’s Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency, in The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics.

Why drugmakers balk

In response to an interview request sent to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Megan Van Etten, the trade group’s senior director for public affairs, emailed a statement expressing concern from the industry that Health Canada’s new regulations “could discourage investment in biomedical research by revealing confidential commercial information.”

Joseph Ross, an associate professor of medicine and public health at Yale University and a co-director, along with Kapczynski and others, of CRIT, maintains that clinical study reports contain little information that companies need to keep secret, and that any such information could be redacted before release. A 2015 report by the Institute of Medicine, now known as the National Academy of Medicine, also called for the FDA to release redacted clinical study reports.

That is the strategy of Health Canada, which discusses possible redactions with the manufacturer. “Health Canada retains the final decision on what information is redacted and published,” Geoffroy Legault-Thivierge, a spokesperson, wrote in an email.

So does the EMA, which goes through a similar negotiating process with manufacturers. “We often are in disagreement but at least there is a dialogue,” says Henry-Eude. The EMA might agree to redact manufacturing details, for example.

Journal reports often underplay harms, emphasize benefits

Researchers who independently re-evaluate drugs say the reports are critical because the data they need is not readily available in medical journal articles. One analysis showed that only about half of clinical trials examined were written up in journals in a timely fashion and a third went unpublished. And when articles are published, they contain much less data than the reports, says Tom Jefferson, an epidemiologist based in Rome who works with Cochrane, an international collaboration of researchers who conduct and publish reviews of the scientific evidence for medical treatments.

In addition, “journal articles emphasize benefits and underplay or, in some cases, even ignore harms” that can be found in the clinical study report data, says Jefferson. An analysis by experts at the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care in Cologne, Germany, found “considerable” bias in how patient outcomes were reported in journal articles and other publicly available sources. Public access to clinical study reports can shine a light on such discrepancies.

The FDA has flirted in the past with releasing clinical study reports to the public. In January 2018, it launched a pilot program to post portions of reports for up to nine recently approved drugs if the drug companies would agree.

“We’re committed to enhancing transparency about the work we do at the FDA,” commissioner Scott Gottlieb, who resigned in March, said at the time.

But only Janssen Biotech, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, volunteered, and its prostate cancer drug Erleada is the lone entry. In June, the FDA announced it is considering shifting its focus from the pilot program to another designed to better communicate the analyses of FDA experts who review drug applications, which the agency has been making public for approved medicinal products since 2012.

But these analyses by FDA reviewers are no substitute for the actual clinical study reports, says Doshi. The reviews reflect “an FDA scientist’s take on the sponsor’s application,” he said. “Without the clinical study report, somebody like me is largely deprived of looking at the underlying data and developing my own take.”

Independent researchers like those who took a hard look at Diclectin also want access to clinical study reports connected to regulatory decisions made before the European and Canadian portals were opened.

Since 2010, the EMA has been providing researchers and others with access to clinical study reports for such legacy drugs upon request, while Health Canada is even more transparent, posting requested clinical study reports for drugs and devices approved or rejected before March to its new online portal for anyone to see. So far, 12 information packages are available for older drugs and devices and 11 more requests are being processed.

The FDA has, on occasion, provided reports in response to a Freedom of Information Act request, but researchers seeking this information typically invest “a tremendous amount of time and effort,” says Ross. For example, a Yale Law School clinic sued the FDA on behalf of two public health advocacy groups after the agency said it could take years to respond to their FOIA request for clinical trial data for two hepatitis C drugs. In 2017, it won the case and the groups received the data, which they are currently evaluating.