High-Ranking Dog Provides Key Training For Military’s Medical Students

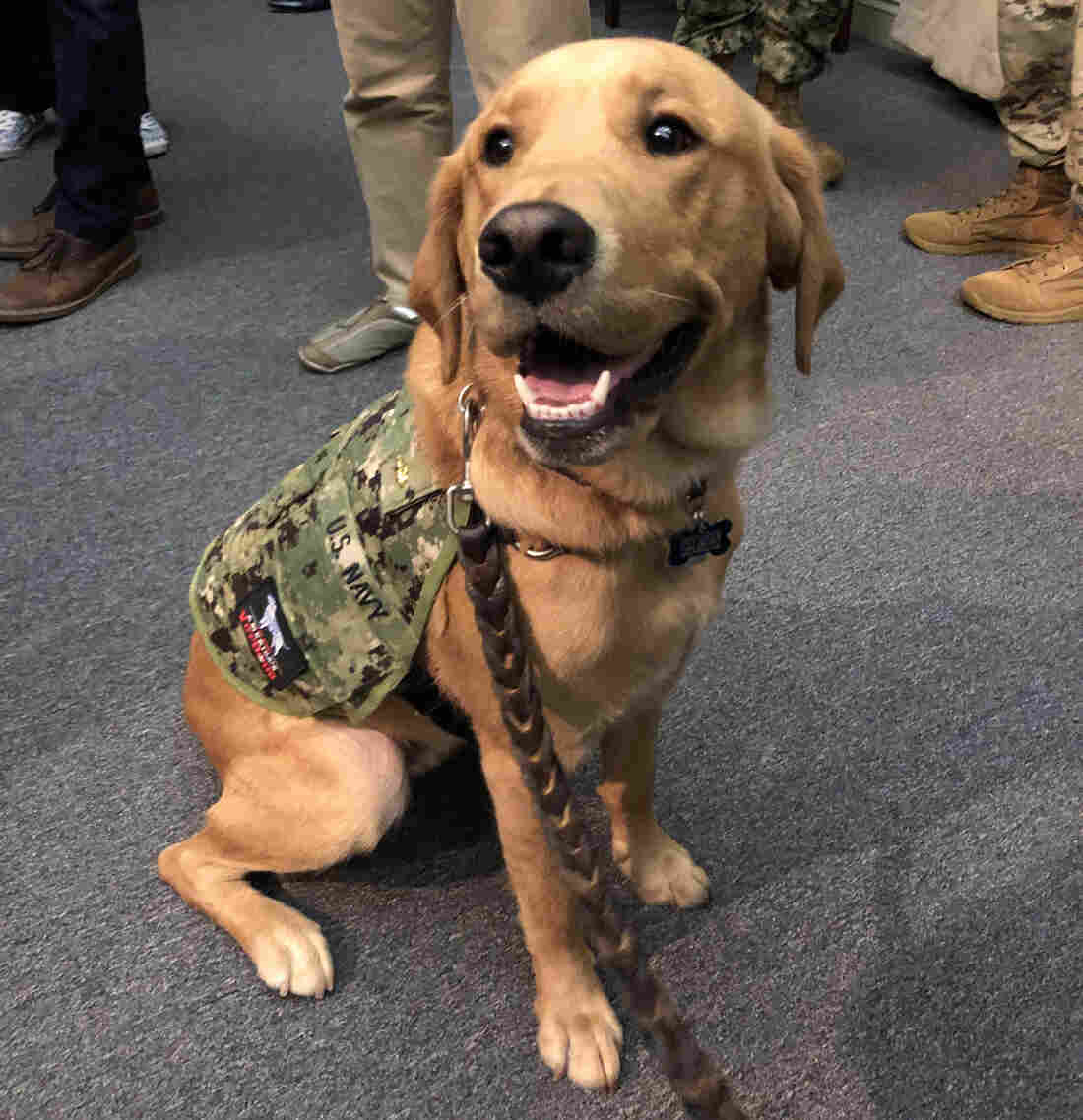

Service dogs can be trained to provide very different types of support to their human companions, as medical students learn from interacting with “Shetland,” a highly skilled retriever-mix.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

The newest faculty member at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences has a great smile ? and likes to be scratched behind the ears.

Shetland, not quite 2 years old, is half-golden retriever, half-Labrador retriever. As of this fall, he is also a lieutenant commander in the Navy and a clinical instructor in the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology at USUHS in Bethesda, Md.

Among Shetland’s skills are “hugging” on command, picking up a fallen object as small as a cellphone and carrying around a small basket filled with candy for harried medical and graduate students who study at the military’s medical school campus.

But Shetland’s job is to provide much more than smiles and a head to pat.

“He is here to teach, not just to lift people’s spirits and provide a little stress relief after exams,” says USUHS Dean Arthur Kellermann. He says students interacting with Shetland are learning “the value of animal-assisted therapy.”

The use of dogs trained to help their human partners with specific tasks of daily life has ballooned since studies in the 1980s and 1990s started to show how animals can benefit human health.

But helper dogs come in many varieties. Service dogs, like guide dogs for the blind, help people with disabilities live more independently. Therapy dogs can be household pets who visit people in hospitals, schools and nursing homes. And then there are highly trained working dogs, like the Belgian Malinois, that recently helped commandos find the Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Shetland is technically a “military facility dog,” trained to provide physical and mental assistance to patients as well as interact with a wide variety of other people.

His military commission does not entitle him to salutes from his human counterparts.

“The ranks are a way of honoring the services [of the dogs] as well as strengthening the bond between the staff, patients and dogs here,” says Mary Constantino, deputy public affairs officer at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. “Our facilities dogs do not wear medals, but do wear rank insignia as well as unit patches.”

USUHS, which trains doctors, dentists, nurses and other health professionals for the military, is on the same campus in suburban Washington, D.C. Two of the seven Walter Reed facility dogs ? Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Sully (the former service dog for President George H.W. Bush) and Marine Sgt. Dillon ? attended Shetland’s formal commissioning ceremony in September as guests.

The Walter Reed dogs, on campus since 2007, earn commissions in the Army, Navy, Air Force or Marines. They wear special vests designating their service and rank. The dogs visit and interact with patients in several medical units, as well as in physical and occupational therapy, and help boost morale for patients’ family members.

But Shetland’s role is very different, says retired Col. Lisa Moores, USUHS associate dean for assessment and professional development.

“Our students are going to work with therapy dogs in their careers and they need to understand what [the dogs] can do and what they can’t do,” she says.

As in civilian life, the military has made significant use of animal-assisted therapy. “When you walk through pretty much any military treatment facility, you see therapy dogs walking around in clinics, in the hospitals, even in the ICUs,” says Moores. Dogs also play a key role in helping service members who have post-traumatic stress disorder.

Students need to learn who “the right patient is for a dog, or some other therapy animal,” she says. “And by having Shetland here, we can incorporate that into the curriculum, so it’s another tool the students know they have for their patients someday.”

The students, not surprisingly, are thrilled by their newest teacher.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, says the Walter Reed dogs used to visit the school’s 1,500 students and faculty fairly regularly, but “having Shetland here all the time is optimal.” Wyatt says the only thing she knew about service dogs before — or at least thought she knew — was that “you’re not supposed to pet them.” But Shetland acts as both a service dog and a therapy dog, so can be petted, Wyatt learned.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, shares a hug with Shetland. The dog’s military commission does not entitle him to salutes.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

Having Shetland around helps the students see “there’s a difference,” Wyatt says, and understand how that difference plays out in a health care setting. Like his colleagues Sully and Dillon, Shetland was bred and trained by America’s VetDogs.

The New York nonprofit provides dogs for “stress control” for active-duty military missions overseas, as well as service dogs for disabled veterans and civilian first responders.

Many of the puppies are raised by a team made up of prison inmates (during the week) and families (on the weekends), before returning to New York for formal service dog training. National Hockey League teams such as the Washington Capitals and New York Islanders also raise puppies for the organization.

Dogs can be particularly helpful in treating service members, says Valerie Cramer, manager of America’s VetDogs service dog program. “The military is thinking about resiliency. They’re thinking about well-being, about decompression in the combat zone.”

Often people in pain won’t talk to another person but will open up in front of a dog. “It’s an opportunity to start a conversation as a behavioral health specialist,” Cramer says.

While service dogs teamed with individuals have been trained to perform both physical tasks and emotional ones — such as gently waking a veteran who is having a nightmare — facility dogs like Shetland are special, Cramer says.

“That dog has to work in all different environments with people who are under pressure. It can work for multiple handlers. It can go and visit people; can go visit hospital patients; can knock over bowling pins to entertain, or spend time in bed with a child.”

The military rank the dogs are awarded is no joke. They can be promoted ? as Dillon was from Army specialist to sergeant in 2018 ? or demoted for bad behavior.

“So far,” Kellermann says, “Shetland has a perfect conduct record.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

HHS Sues Drugmaker Gilead Over PrEP Patent Infringement

The federal government is suing drugmaker Gilead for alleged patent infringement. The suit charges the company violated patents on “PrEP” drugs that are used to prevent HIV infection.

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

The Trump administration is taking the highly unusual step of suing a drugmaker. Specifically, the Department of Health and Human Services has filed a lawsuit against Gilead Sciences. The issue is patent infringement. HHS says Gilead has been infringing on its patents for PrEP. This is a drug regimen that prevents HIV infection.

All right. To help us understand all this, we’re going to bring in NPR health policy reporter Selena Simmons-Duffin. Hi, Selena.

SELENA SIMMONS-DUFFIN, BYLINE: Hi.

KELLY: What exactly is PrEP?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: So PrEP stands for pre-exposure prophylaxis. It’s recommended for people who are at high risk for HIV infection. There are only two drugs currently approved for this, and both of them are made by Gilead. Truvada is the one that’s been used for PrEP since 2012 – very few side effects. It’s a daily pill. It’s almost 100% effective in preventing HIV infection.

But only a fraction of the 1 million people who are at risk for getting HIV are on it. And a big part of that – the reason for that is the price. So the list price here is $1,800 a month. A generic overseas is about $6 a month.

KELLY: Wow. OK.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: So – yeah. Gilead maintains it invented Truvada. It spent about a billion dollars on R&D. But the CDC worked on developing the PrEP regimen, too, with taxpayer money. So there’s an activist group called PrEP for All that has been calling for months on the government to defend its patents. And last night with this lawsuit, it seems like the Trump administration is doing what these activists wanted.

KELLY: So they must be over the moon. I’m guessing…

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Yeah.

KELLY: …The reaction has been positive.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Very, very pleased; also very surprised. One activist I talked to today said it seemed like they’d been screaming into the void about this, but maybe someone was actually listening.

KELLY: And why is the government – what have they indicated about why they were listening now, and what’s their argument?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: So this complaint is very strongly worded. I’m going to – here – read part of it to you. Gilead’s conduct was malicious, wanton, deliberate, consciously wrongful, flagrant and in bad faith.

So basically, in general, HHS has lots of patents – thousands of patents. And usually, what happens is they license these patents out to companies and get paid royalties. Gilead didn’t do that. So the Financial Times did an analysis over the summer that Gilead owes the government about a billion dollars in royalties. And this complaint asks for enhanced damages, so they could be getting a lot more than that.

KELLY: I’m trying to situate this in terms of where we are as a country with the HIV epidemic because the Trump administration set that goal – right? – that they were going to try to end the HIV epidemic by 2030. Is this a piece of that?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Yeah. I think that the HHS is – been trying to reach that goal, and having Gilead set this very high price for this drug that they need to use to get the epidemic to stop has been a frustration. And I think that HHS and Gilead have been negotiating in good faith, it seems like. And this strongly worded lawsuit makes it seem like the government had enough. So just to remind everybody where we are in this epidemic, 40,000 people still get HIV infections every year here in the U.S.

KELLY: New infections every year.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: New infections every single year. And you know, this is a beginning of a lawsuit. It’s a court process. It might take a really long time to sort out, but activists I talked to today think that it could be leverage to get actual concessions from Gilead, and they’re really hopeful that that may happen.

KELLY: And real quick – statement from Gilead today.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: So Gilead maintains that it thinks that HHS’s lawsuits are invalid.

KELLY: All right. That is NPR’s Selena Simmons-Duffin. Thank you.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Federal Judge Throws Out ‘Conscience Rights’ Rule For Health Care Workers

A federal judge has thrown out the Trump administration’s “conscience rights” rule for health care workers.

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Religious freedom has been a major focus of the Department of Health and Human Services under the Trump administration. Today there was a major blow to those efforts. A federal judge in Manhattan has thrown out a rule from HHS designed to protect the so-called conscience rights of health care workers.

Here to explain is NPR health policy reporter Selena Simmons-Duffin. Hey, Selena.

SELENA SIMMONS-DUFFIN, BYLINE: Hi.

CHANG: So can you just first explain, what are conscience rights? What does that even mean?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Right. So this relates to the HHS Office for Civil Rights, and that’s an office that receives complaints in three different categories. The biggest is patient privacy, like HIPAA. It also receives complaints of civil rights violations.

And then this last court category is conscience rights. So what that means is a doctor or a nurse who has religious objections to certain procedures or services – commonly, we talk about abortion, care for transgender patients, assisted suicide – if a doctor or nurse like that is forced to participate in that kind of care, they can file a complaint that their conscience rights have been violated to the Office for Civil Rights. And the director of that office is Roger Severino. He has made clear since he came in that religious freedom and conscience rights is his priority in that role, and that’s the context for this rule.

CHANG: OK. That’s the context. So when the rule came out in May, what did this rule do?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: So the things that it did is it expanded who could file that type of a complaint that I just described to billing staff, scheduling staff. A doctor or nurse or this other kind of health worker did not have to give their employer prior notice that they objected to give this kind of care. There were no exceptions for medical emergencies. If a hospital, for instance, was found to have violated a health care worker’s conscience rights, HHS could have taken away all of its federal funding.

CHANG: Wow.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Yeah. So…

CHANG: It’s a large consequence.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Yeah, really big consequences. So part of the justification for issuing this rule is the office said that there was this big unmet need, that providers of faith were being forced to do things all over the country. Historically, there’s only been one of these kind of complaints that’s come into the office every year. That’s been for the last 10 years or so.

CHANG: OK.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: But Severino keeps on saying that that number of complaints has just shot up. And he said last year, the office got 343 complaints.

CHANG: Wow, that’s quite an ascent. But after this rule came out, wasn’t it immediately challenged in court?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Yes. It was – the HHS was sued right away in this case by Planned Parenthood, the state of New York, lots of other states and cities and organizations. And today, what happened is the U.S. District Court Judge Paul Engelmayer of the Southern District of New York vacated the rule. He found the rule’s violations of federal law were, quote, “numerous, fundamental and far-reaching.” And he also found that HHS exaggerated the need for this rule. So remember I was just talking about 343 complaints.

CHANG: Right, the number of claims that came in last year. What about them?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Right. So apparently, that’s an – a made-up number. The government submitted…

CHANG: Really?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: …These complaints.

CHANG: OK.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: And the court analyzed them and says, instead of 343, the real number is 20. A government lawyer said on the record that that is the ballpark for the complaints that have come into the office. So the judge called that admission fatal to HHS’s justification.

CHANG: Three hundred forty-three versus 20 – that’s quite a discrepancy.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Yes.

CHANG: OK. So what’s next in the litigation?

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: So there is weirdly another case against this rule in another district court. This one is in the Northern District of California. A ruling is expected there, but it’s not clear what happens now that the rule’s been vacated. I asked HHS what’s next, and it would not comment on a possible appeal – only said that it was reviewing this court’s opinion.

CHANG: That’s NPR’s Selena Simmons-Duffin. Thanks, Selena.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Thank you.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

This Ohio Addiction Recovery Program Uses Opioid Settlement Money To Help Patients

With opioid settlement money, Ohio’s Cuyahoga County created an addiction recovery program that helps patients after they’re discharged from the ER. Now, officials want to expand the program.

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Many people who survive drug overdoses spend time in emergency rooms. After being discharged, they face a high risk of overdosing again. Some communities are trying a hands-on approach to prevent that cycle by connecting patients with coaches who have gone through the rigors of addiction recovery themselves. Nick Castele reports on efforts to expand that approach by using settlement money from opioid lawsuits.

NICK CASTELE, BYLINE: This fall, two northeast Ohio counties were slated to be the first to go to trial in a nationwide lawsuit over the opioid crisis, but the defendants offered more than $300 million in cash and drug products to settle the case, and the counties accepted. While more than 2,500 other plaintiffs nationwide are still waiting for a universal settlement that could top tens of billions, Cuyahoga and Summit Counties have their settlement money on the way, and they’re planning to spend much of it on anti-addiction programs, including hiring more people like Christopher Hall. Hall is neither a doctor nor a nurse, but at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, he offers patients struggling with addiction something unique – common ground.

CHRISTOPHER HALL: I was addicted. I used heroin for 15 years. I grew up with alcoholism. I know what you’re going through, and that really gets them to let their guard down and talk. And they’re very relieved.

CASTELE: Once Hall gets patients talking, he tries to sign them up for additional help like detox or residential treatment. He’s part of a peer recovery program at MetroHealth. So far, the hospital has been happy with the results of its 2-year-old program. Dr. Joan Papp oversees opioid safety for the hospital and says it takes a lot of time and resources to support people in treatment. That’s time that hospital emergency departments rarely have.

JOAN PAPP: With the help of a peer supporter – somebody there to really guide you and hold your hand and, in many cases, drive you directly to treatment – that is just a world of difference.

CASTELE: Now this Cleveland-area county wants to use opioid settlement money to fund peer coaches at other local hospitals. If successful, that could help more people with opioid addiction like Patricia Withrow. She met her peer supporter at a local treatment center in Cleveland.

PATRICIA WITHROW: She’s a big part of my life, actually. My day – if I don’t talk to her at least once a day, I feel incomplete.

CASTELE: Withrow has been sober for 17 months. When she had a recent cancer scare, she says her supporter talked to her kids to help reassure them. That kind of stress could push someone to relapse, Withrow says, but she’s been doing well.

WITHROW: It’s taught me how to have actual relationships with people that are positive. She taught me that. She taught me how to set boundaries.

CASTELE: Withrow is referring to her peer supporter, Nicole Betzner. Betzner says she helps her clients work through the messy parts of their lives that can get in the way of recovery.

NICOLE BETZNER: If their home environment is toxic or relationships, or if they have barriers with food, clothing, shelter, transportation, all of those things – kind of unraveling that, but ultimately, also helping a person just recover from different traumas and issues of life.

CASTELE: Over the past five years, as the opioid crisis has deepened, peer support programs have been catching on, launching in New York City, Rhode Island, Indiana and elsewhere. Dr. Elizabeth Samuels at Brown University coordinates with hospitals in Rhode Island. While the results are still coming in, she says, hospital peer support programs seem to be effective.

ELIZABETH SAMUELS: They’ve been in that person’s shoes. They know what it’s like. They treat them like a human being. They give them respect.

CASTELE: As this Ohio county moves forward, other communities are still awaiting their share of settlement dollars to help bring people with addiction back from the edge of crisis.

For NPR News, I’m Nick Castele in Cleveland.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

This Congolese Doctor Discovered Ebola But Never Got Credit For It — Until Now

Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe first encountered Ebola in 1976, before it had been identified. Since then, from his post at the Congo National Institute for Biomedical Research, he has led the global search for a cure.

Samantha Reinders for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Samantha Reinders for NPR

Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe says his story starts in 1973. He had just gotten his Ph.D. at the Rega Institute in Belgium. He could have stayed in Europe, but he decided to return to Congo, or what was then known as Zaire, which had only recently attained independence from Belgium.

If he had stayed in Belgium, he says, he would have been doing routine lab work. But in Congo, he would be responsible for the “health of my people.”

“But when I arrived here the conditions of work were not good,” he says. “I had no lab; I had no mice for the experimentation, so it was very difficult to work here.”

Being a microbiologist without mice or a lab was useless, so he took a job as a field epidemiologist. In 1976, he was called to an outbreak of a mysterious disease in central Congo.

Lots of people had died of something that presented like yellow fever, typhoid or malaria. Muyembe arrived to a nearly empty hospital. He says people thought the infection was coming from the hospital, and he found only a mother and her baby.

Muyembe says his biggest legacy won’t be discovering Ebola. It will be that in the future, another young Congolese researcher could be able to do more of their work in their home country, rather than relying on peers in the U.S. or Europe.

Samantha Reinders for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Samantha Reinders for NPR

“I thought that it was malaria or something like this,” he says. “But in the night the baby died, so the hospital was completely empty.”

By morning, as the people of Yambuku heard Muyembe had been sent by the central government in Kinshasa, they started lining up at the hospital hoping he had medicine for them.

“I started to make physical exam,” he says. “But at that time we had no gloves in the whole hospital.”

And, of course, he had to draw blood, but when he removed the syringes, the puncture would gush blood.

“It was the first time for me to see this phenomenon,” he says. “And also my fingers were soiled with blood.”

Muyembe says he washed his hands, but it was really luck that kept him from contracting an infection. He knew immediately this was something he’d never seen before. Some of the Belgian nuns in the village had been vaccinated against yellow fever and typhoid, but this disease was different. It was killing people fast. When he took liver samples with a long needle, the same thing would happen — blood would continue to gush.

He persuaded one of the nuns who had the disease to fly with him to Kinshasa. He took blood samples before she died and sent them to Belgium, where they had an electron microscope to try to identify the culprit. Scientists there and in the United States saw this was a new virus that caused hemorrhagic fever.

They named it Ebola, after a river near the village.

The discovery, says Muyembe, was thanks to a “consortium of research.”

But Google “Who discovered Ebola?” and you get a bunch of names — all of them white Western males. Dr. Jean Jacques Muyembe has been written out of history.

“Yes, but it is …” he pauses. He takes a breath and laughs, looking for the right way to respond.

“Yes. It is not correct,” he says. “It is not correct.”

***

The man who gets the bulk of the credit for discovering Ebola is Dr. Peter Piot. At the time, he was a young microbiologist at the Institute for Tropical Medicine in Belgium. He was the one to receive the blood samples sent by Muyembe.

He describes his experience in No Time to Lose, a book about his professional life, including his vast work on HIV.

But Ebola was his big break. In the book, he describes how vials of blood had arrived in melting ice, some of them broken.

He describes how the World Health Organization ordered them to give up the samples, to send them to England and eventually the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, which was one of the only labs equipped to handle a deadly virus like Ebola.

He describes how angry that made him and Dr. Stefaan Pattyn, the man running the lab at the time, who died in 2008.

“[Pattyn] claimed that we needed a few more days to ready it for transport,” Piot wrote. “So we kept a few tubes of VERO cells, as well as some of the newborn mice, which were dying. Perhaps it was a stubborn rebellion against the whole Belgian history of constantly being forced to grovel to a greater power. That material was just too valuable, too glorious to let it go.”

Almost simultaneously, scientists at the CDC and Piot looked at the samples under an electron microscope and saw a snakelike filament — huge in comparison to other viruses and very similar to the Marburg virus. The CDC, which kept the world’s reference lab for hemorrhagic viruses, confirmed this was something new. This was Ebola.

***

The Congo National Institute for Biomedical Research sits in the middle of Kinshasa.

There are ragged couches along the corridors and goats feeding in the courtyard. But this is where the bulk of the science is being done on the second largest Ebola outbreak in history.

Tucked in corners around the building, there are high-tech labs. Scientists in full biohazard suits run Ebola samples through sophisticated machines that spit out DNA sequences. On the bulletin boards outside the offices, scientists have pinned papers published in international journals about the science done right here.

Workers are constantly dragging in boxes of brand-new scientific gear. On this day, almost all of them are stamped with the American flag.

It’s no secret there is resentment among scientists here about what many believe is a marginalization of their work by the West.

Joel Lamika, who runs an Ebola smartphone app at the institute, says many foreign governments want to stamp their flags on the work Congolese have done.

“They want to claim like it’s theirs,” he says. “But it is theft.”

Lamika says perhaps one good thing that has come out of this latest Ebola outbreak is that it is giving the world a chance to rewrite history.

Muyembe, he says, is a national hero. His picture is on a huge banner in front of this institute. During previous Ebola outbreaks, and especially the huge one in West Africa that killed more than 11,000 people, the the scientific community used Muyembe as an example of someone who had gotten it right. Under his leadership, Congo had managed to quickly quell nine previous outbreaks.

Maybe this outbreak, he says, will give the world an opportunity to know who Muyembe is.

“It’s time for the world to learn that Ebola was discovered by a Congolese,” he said. “By Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe.”

***

Today, Peter Piot is the director of the prestigious London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He’s friends with Muyembe and expresses nothing but admiration for not only his scientific prowess, but the way he has managed public health emergencies.

But in his book, he mentions Muyembe only in passing, as a bright scientist constantly pressuring Piot for more resources.

When asked if he feels responsible for writing Muyembe out of history, Piot pauses.

“I think that’s a fair comment,” he says. “But my book was not an attempt to write the history of Ebola, but more my personal experience.”

Piot says at the time of that first Ebola outbreak, African scientists were simply excluded. White scientists — with a colonial mentality — parachuted in, took samples, wrote papers that were published in the West and took all of the credit.

But things are changing, he says. Muyembe, for example, is finally starting to get his due. He was recently given a patent for pioneering the first treatment for Ebola and he has received several international awards, including the Royal Society Africa Prize and, just this year, the Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize.

“That reflects, I think, the [change in] power relations in global health and science in general,” he said.

During this outbreak, Muyembe has also made a decision many thought unthinkable even a few years ago. He decided that all of the blood samples collected during this Ebola epidemic will stay in Congo. Anyone who wants to study this outbreak will have to come to his institute.

American scientists, who have led the way in studying Ebola, have privately expressed frustrations. But Piot says the decision was obviously made because of how African scientists have been treated. Western scientists, he says, should get over it.

“We have to wake up to two things,” he says. “One, the world has changed. And two, it’s a matter of fairness.”

***

Muyembe keeps his office ice cold, and when he talks, he nervously drums a pen against his notebook. He’s terribly serious about his work, but he also offers an easy smile as he remembers his work.

The thing that makes him glow is talking about the treatment he developed.

“It is the most important achievement of my life,” he says.

In 1995, during another outbreak, he wondered whether antibodies developed by Ebola survivors could be siphoned from their blood and used to treat new cases. So he injected Ebola patients with the blood of survivors, taking inspiration from a practice used before sophisticated advances in vaccine-making.

“We did eight patients and seven survived,” he says.

The medical establishment wrote him off. He didn’t have a control group, they told him. But Muyembe knew that in this village, Ebola was killing 81% of people. Just this year, however, that science became the foundation of what is now proven to be the first effective treatment against Ebola, saving about 70% of patients.

“But if this idea was accepted by scientists, we [could have] saved a lot of people, a lot of lives,” he says.

You can tell Muyembe is hurt by all this. Ever since he returned to Congo, he has fought for recognition for his country. His whole life, he has dreamed that big science could come out of his home country.

Just as he announced that samples would not leave Congo, he also got a commitment from Japan to build a state-of-the-art research facility right here. Soon, the goats in the courtyard will be gone, replaced by a facility just as good as those in Belgium or in the United States.

At 77, Muyembe says he doesn’t regret coming back to Congo. And, unlike when he returned in 1973, now he has equipment.

“Now I have mice here,” he says, laughing. “I have mice. I have subculture. Now, everything is here.”

His biggest legacy, he says, won’t be that he helped to discover Ebola or a cure for it. It’ll be that if another young Congolese scientist finds himself with an interesting blood sample, he’ll be able to investigate it right here in Congo.

Open Enrollment For 2020 Health Care Plans

This year, as open enrollment kicks off, the federal health insurance marketplace Healthcare.gov has a few new bells and whistles.

LULU GARCIA-NAVARRO, HOST:

For people who get their health insurance through the Obamacare exchanges, it’s that time of year again. Open enrollment for healthcare.gov kicked off on Friday. The website has been through a lot over the years. It had a famously rocky start in 2013, even as President Obama described his vision for how easy it would be to pick a health plan.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

BARACK OBAMA: Just visit healthcare.gov, and there, you can compare insurance plans side by side the same way you’d shop for a plane ticket on Kayak or a TV on Amazon.

GARCIA-NAVARRO: Every year, there have been tweaks to make things run more smoothly. As NPR’s Selena Simmons-Duffin reports, this year, there’s a new feature that makes it look a bit more like the website President Obama originally envisioned.

SELENA SIMMONS-DUFFIN, BYLINE: Star ratings – the plans you see are rated out of five stars based on information submitted by insurers and the experience of customers enrolled in the plans, just like on Yelp or Amazon.

LOUISE NORRIS: I definitely wouldn’t recommend basing your whole plan selection decision on the star ratings, but it’s another little tool people can use.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: That’s Louise Norris. She’s an insurance broker who writes about health policy for healthinsurance.org.

NORRIS: Not every plan will have them because if the plan is new, obviously, it doesn’t. And then if a plan is too small, it doesn’t have it.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: And there’s no guarantee you’ll have access to plans with four or five stars. In some states, there are no plans with more than three stars.

There’s another feature Dr. Charlene Wong likes. She’s a professor at Duke University who studied how people make health insurance choices.

CHARLENE WONG: This tool called the estimated total yearly cost – a lot of people we know from past research become overly focused on the monthly premium and may not pay as much attention to things like the deductible or how much the copayments are.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: Even with these tools, it can be daunting to pick the right plan. Wong knows it’s hard because she’s picked the wrong one. A few years ago, she got pregnant, and her bills from her prenatal visits with an in-network doctor were through the roof.

WONG: It turns out my original preferred provider was actually in Tier 3 of a tiered network.

SIMMONS-DUFFIN: She had to change doctors to keep her costs down. So take heart – this stuff is complicated, even for the experts.

Selena Simmons-Duffin, NPR News.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Voters Weigh In As Elizabeth Warren Takes Health Care Plan On Campaign Trail

Sen. Elizabeth Warren released a plan to pay for “Medicare for All” without raising taxes on the middle class, and now she’s on the campaign trail talking about it.

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

Impeachment aside, health care has emerged as a dominant campaign issue for Democrats this presidential election season. The idea of better, cheaper health care is popular with primary voters. But the idea of eliminating private insurance and replacing it with a government-run system is less popular. Still, that’s what Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren is endorsing. And yesterday, she released her plan explaining how she intends to pay for it. NPR’s Asma Khalid is with Warren on the campaign trail in Iowa.

ASMA KHALID, BYLINE: The first stop of the day for Elizabeth Warren was a rally at a high school in Vinton, a small town with a population around 5,000. Warren did not mention her “Medicare for All” plan in her speech. But the first question she got from the crowd, from Dee Patters, was about health care and specifically what would happen to people like her who depend on unusual lifesaving drugs.

DEE PATTERS: I wholeheartedly support universal health care. But I also worry about the transition and whether or not the continuity of care will be able to be there as we transition to “Medicare for All.”

KHALID: Warren told the crowd that her goal is to improve health care.

ELIZABETH WARREN: No insurance company in the middle to say, sorry, that doctor is out of network. No insurance company in the middle to say, I’m sorry, we don’t authorize that treatment.

KHALID: And her plan, she says, would save middle-class families money.

WARREN: We should be an America where you get the health care that you need and that no one goes broke over it.

KHALID: I caught up with Patters after the rally. She told me she’s not sure who she’s going to caucus for – either Warren or California senator Kamala Harris. She gestured to her partner and explained that they don’t think a public option being offered by some other candidates is enough. But she wants to hear more from Warren about how the country would transition to “Medicare for All.”

PATTERS: We believe in universal health care, but it’s that, you know, nagging, like, am I still going to be able to get everything I have now?

KHALID: Yesterday, Warren laid out an ambitious plan that explains how she would pay for “Medicare for All.” It’s a question she’s been badgered with for months on the campaign trail and on the debate stage. Her plan calls for higher taxes on the wealthy, cuts to defense spending and diverting money to the government that employers already pay to insurance companies.

CHRIS VAN WAUS: I appreciate that she did lay out the information and details. I think that’s good. It wasn’t really necessary for me.

KHALID: That’s Chris Van Waus, who was listening in the front row today with his daughter.

VAN WAUS: In the end, I think it’s really a value judgment more than just purely a money judgment for me. Even if my taxes go up a little bit, I’m still supportive of “Medicare for All” because I think it’s the right policy for America.

KHALID: Warren has insisted her plan will not increase taxes on the middle class. An NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll found that a majority of Americans actually do not support eliminating private insurance in exchange for “Medicare for All,” and that’s what worries Mary O’Hearn.

MARY O’HEARN: I’m all about winning this time around. It’s been a hard two and a half, three years.

KHALID: We met at a Biden rally the other day. She likes Warren. She thinks she’s smart and good at explaining her ideas.

O’HEARN: But there’s one thing about Elizabeth that I – I like if you like your health care, you can keep with that. That’s the thing that I feel strongly about.

KHALID: How strongly could be key. It’s not unusual to find voters who are uncertain about “Medicare for All” but like Warren as a candidate. The question is whether they’ll stick with her.

Asma Khalid, NPR News.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Open Enrollment Is Here: 6 Tips For Choosing A Health Insurance Plan

HealthCare.gov provides tools to guide you cost comparisons when you’re choosing a health care plan.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

It’s the season to roll up your sleeves, gather your documents, and pick a health insurance plan for 2020. For those shopping for their own plans, HealthCare.gov and the other state exchanges are open for enrollment as of November 1.

Despite the rhetoric about the implosion of the Affordable Care Act, the individual mandate going away, and other attempts to hobble the law, the marketplaces are still alive and well. And many people are eligible for subsidies to bring their costs down.

In fact, HealthCare.gov has gotten sleeker and easier to use over the years (after a famously rocky start). There are new bells and whistles to make shopping for a plan easier this year. Still, figuring out how to balance premiums, deductibles and other costs, and choose a plan that will fit your needs for the coming year is hard.

Charlene Wong knows this from experience. Even as a doctor and academic at Duke University who studies how people make health insurance choices, a few years ago, she and her husband picked the wrong plan.

“We spent several days researching plans and called around to make sure the doctors we wanted to see were in network,” she says. Then she got pregnant, and found that while her OB was in network, there was a catch.

“There was a tiered network within that health insurance plan and [my OB] was in Tier 3 of network providers,” she explains. Even though she thought she’d done everything right, she ended up having to switch doctors to keep her costs down.

So take heart — health insurance can be tricky, even for the experts. Here are a few tips to help you find the right plan.

1 – Figure out where and when you need to enroll

Depending where you live, you can either use the federal exchanges on HealthCare.gov or your state’s marketplace to shop for insurance. Twelve states and the District of Columbia run their own exchanges. The federal exchange open enrollment runs until mid-December, but you might have more time if you live in a state that runs its own marketplace.

2 – Review plan options, even if you like your current one

For people who are already enrolled in an ACA plan, Charles Gaba says it’s really important to log in and check if there’s a better value, even if you’re happy with your current plan. Gaba runs the website ACAsignups.net, where he does health care data and policy analysis, focused primarily on the Affordable Care Act.

It can be tempting to skip the whole enrollment rigmarole, especially since you’ll just get rolled into the same plan or a similar plan if you do nothing during open enrollment.

“A lot of people think that because nothing changed in their lives — like, their income is the same, the same household — nothing will change for their policy or their premiums, and that’s just not true,” Gaba says.

Every year, there can be all sorts of changes that affect the kinds of plans available and the costs of those plans. For instance, this year new insurers have entered the marketplace, and premiums have gone down in some states. It’s always worth logging in and checking to see what’s changed for you and whether it makes sense to switch things up.

3 – Compare estimated yearly costs, not just monthly premiums

It’s easy to focus on the monthly premium payment when comparing plans, but Wong at Duke says don’t forget to consider other costs as well.

“A lot of people — we know from past research — become overly focused on the monthly premium and may not pay as much attention to things like the deductible or how much the co-payments are,” Wong says.

The premium price is prominently featured when you’re looking at plans, but look at other costs too. A tool available on HealthCare.gov and some state marketplaces will calculate “estimated total yearly costs” for you. This takes into account the plan’s deductible — how much you have to pay out-of-pocket for covered services before your insurance picks up the tab — and copays, put together with how much health care you expect to use in the coming year.

Wong says that yearly cost estimate can be a really useful tool when picking a plan. “Trying to figure out that math can be a little bit tricky, especially for people who are not as familiar with health insurance.” she says.

4 – Consider how much health care you use

Picking the right insurance plan involves guesswork about how many health issues you’re likely to face in the coming year, which could affect the way costs break down. Your age is usually a useful proxy for this, but there’s always a lot of unknowns, like a surprise cancer diagnosis or a car accident.

Wong points out there are basic tradeoffs to consider. “You might want to think about, ‘Do I pay a little bit more each month in a monthly premium knowing that that would mean less out-of-pocket expenses when and if I do need more medical care?” she says. “Versus — the other way around — ‘Let me pay a lower monthly premium because I don’t really anticipate needing much care, but I know I’d have this health insurance in case something really catastrophic happens.’ “

Alongside these unknowns, leverage what you do know about your health needs. If you have a doctor you like, or if you know you’re going to take a certain prescription drug, look for a plan that covers them. HealthCare.gov allows you to add your provider and your prescription drugs as you browse plans to see whether they’re covered. Another way to find out is simply call your doctors and ask what plans they accept, says Wong.

5 – Beware too-good-to-be-true plans

If you see a good deal online, make sure you’re looking at an ACA plan, warns health policy writer and insurance broker Louise Norris. When you search for health insurance on the internet, you may stumble on short term plans that advertise much lower monthly premiums, but don’t cover the ACA’s famous ten essential benefits. These include some pretty important stuff like prenatal care and mental health treatment.

Sometimes people can find good deals on premiums in the federal and state marketplaces, Norris says, but if one plan sticks out as being too good to be true, read the fine print.

“I did see some new plans popping up in some areas for 2020 where they’ll say $0 deductible,” she says. “Then you scroll down a little bit further and you have maybe $1,000 a day copay for hospitalization.” You hope you won’t spend a lot of time in the hospital, but if you do, that kind of cost could really add up.

Norris points out a new tool this year to help sort out good plans from bad — a star rating, similar to what consumers are used to on Yelp or Amazon (hearkening back to Obama’s original vision). The star ratings are based on information insurers submitted regarding cost, combined with enrollee feedback.

“Star ratings are one of those at-a-glance things where you can kind of see, “OK, how do other customers feel about this plan?’ ” Norris says. Not all plans have them since some are new, she says, but for plans that do, the stars “give you some some red flags if maybe there are some concerns.”

6 – Get free help from the pros

The Trump administration slashed federal funding for advertising open enrollment and the navigator program, but those programs do still exist: There are still people across the country trained and ready to sign people up — for free.

“My best piece of advice for people — particularly those who are less familiar with insurance, is to see if you can get some help,” Wong says. You can call for help, but she recommends trying to meet in person with “a health insurance navigator or a certified application counselor,” she says. “Importantly, these are folks who are impartial to which health insurance plan may be best for you.”

Katie Turner is one of those trained navigators — she’s been signing people up for seven years, and works with the Family Health Care Foundation in the Tampa Bay, Fla., area. Leading up to open enrollment, she’s been busy calling consumers from past years, letting them know that this is the time.

She advises people to assemble all the necessary documents, such as Social Security cards, immigration documentation, tax returns, before going into a meeting with a navigator.

Most of all, she says, don’t miss your chance to sign up for coverage if you need it.

“There is a lot of confusion out there,” Turner says. Many people are confused about what a legal challenge to the law means for the marketplaces (nothing for now), when open enrollment is, and more. “All we can do,” Turner says, “is continue to be here and provide the resources that we’ve been providing for the last seven years to help people enroll in coverage.”

Fate Of Missouri’s Only Abortion Clinic To Be Decided

A hearing this week will determine the fate of Missouri’s only remaining abortion clinic. State officials are fighting against Planned Parenthood in an effort to shut down the clinic.

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

In St. Louis, a weeklong hearing that could determine the fate of Missouri’s only abortion clinic ended today. Lawyers for the state argued that the clinic was the site of significant safety issues. Planned Parenthood lawyers argue that Missouri is treating the clinic differently in a politicized effort to close it. St. Louis Public Radio’s Chad Davis reports.

CHAD DAVIS, BYLINE: Lawyers representing Missouri and Planned Parenthood have been arguing over the state’s only abortion health care clinic for months now. Earlier this year, Missouri refused to extend the license for the Planned Parenthood clinic in St. Louis, citing four instances where patients experienced complications following abortion procedures. M’Evie Mead, the director of policy and organizing for Planned Parenthood Advocates of Missouri, says the clinic is being targeted.

M’EVIE MEAD: What we have is an agency and a director that appear to be obsessed with attacking access to abortion.

DAVIS: The state’s administrative hearing commission extended Planned Parenthood’s license, allowing the clinic to remain open until a decision on the case is made. Planned Parenthood officials say from time to time, complications do occur. They argue that focusing on these four cases is unfair since the clinic sees thousands of patients a year. They also criticized how the records have been requested and stored for some Planned Parenthood patients. The Missouri Department of Health revealed at the hearing this week that it collected data on some patients’ menstrual cycles to see if there have been failed abortions.

That news has sparked controversy across the state, with several politicians calling on the governor to investigate health director Randall Williams. Some legal professionals have been puzzled by this revelation, including Mary Ziegler, who teaches law at Florida State University. She spoke to Kansas City’s KCUR.

MARY ZIEGLER: There is a history of record-keeping laws being introduced into abortion restrictions – so requiring clinics to submit certain records to the state. So it’s not an entirely new strategy, but I’ve never heard of anyone keeping records of menstrual periods.

DAVIS: But state officials say Williams did not authorize the recording and that he hadn’t seen any of the data until he was deposed earlier this month. Lisa Cox is the communication director for the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services.

LISA COX: Do we have a spreadsheet with every Planned Parenthood patient’s menstrual cycles on it? Absolutely not.

DAVIS: State officials also maintain that patient privacy was not compromised during the data collection. Anti-abortion activist Kristi Hamrick is among those pushing hard for the state’s final clinic that performs abortions to close.

KRISTI HAMRICK: It doesn’t matter how many people are harmed. What matters is what has happened to the people at that vendor.

DAVIS: But Planned Parenthood officials say the number does matter and that the closure would negatively affect women all across Missouri. Dr. Colleen McNicholas is a medical officer for Planned Parenthood and says the four cases are in line with Missouri’s acceptable and legal health standards. She says using them to deny access to all patients is just wrong.

COLLEEN MCNICHOLAS: Abortion is health care. There will be times when there are complications – doesn’t demonstrate any systematic or systemic-wide problem. Abortion is health care, and we’ll continue to provide that quality health care and fight for people to have access to that.

DAVIS: A decision on whether the Planned Parenthood clinic will remain open will be decided later this winter.

For NPR News, I’m Chad Davis.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Firms Seeking Top Workers Find They Can’t Offer Only High-Deductible Health Plans

For the third year in a row, the percentage of companies that offer high-deductible plans as the sole health insurance option will decline in 2020, according to a survey of large employers by the National Business Group on Health.

PeopleImages/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

PeopleImages/Getty Images

Everything old is new again. As open enrollment gets underway for next year’s job-based health insurance coverage, some employees are seeing traditional plans offered alongside or instead of the plans with sky-high deductibles that may have been their only choice in the past.

Some employers say that in a tight labor market, offering a more generous plan with a deductible that’s less than four figures can be an attractive recruitment tool. Plus, a more traditional plan may appeal to workers who want more predictable out-of-pocket costs, even if the premium is a bit higher.

That’s what happened at Digital River, a 650-person global e-commerce payment processing business based in Minnetonka, Minn.

Four years ago, faced with premium increases approaching double-digit percentages, Digital River ditched its traditional preferred provider organization plan in favor of three high-deductible plans. Each had different deductibles and different premiums, but all linked to health savings accounts that are exempt from taxes.

This year, though, the company added back two traditional preferred provider plans to its offerings for workers.

Even with three plan options, “we still had employees who said they wanted other choices,” says KT Schmidt, the company’s chief administrative officer.

Digital River isn’t the only company broadening its offerings. For the third year in a row, the percentage of companies that offer high-deductible plans as the sole option will decline in 2020, according to a survey of large employers by the National Business Group on Health. A quarter of the firms polled will offer these plans as the only option next year — down 14 percentage points from two years ago.

That said, high-deductible plans are hardly disappearing. Fifty-eight percent of covered employees worked at companies that offered a high-deductible plan with a savings account in 2019, according to an annual survey of employer health benefits released by the Kaiser Family Foundation last month.

That was second only to the 76% of covered workers who were at firms that offered a PPO plan. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation; it is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

When Digital River switched to exclusively high-deductible plans for 2016, the firm put some of the $1 million it saved into the new health savings accounts that employees could use to cover their out-of-pocket expenses before reaching the deductible.

Employees could also contribute to those accounts to save money for medical expenses. This year the deductibles on those plans are $1,850, $2,700 and $3,150 for single coverage, and $3,750, $5,300 and $6,300 for family plans.

The company put a lot of effort into educating employees about how the new plans work, Schmidt says. Premiums are typically lower in high-deductible plans. But under federal rules, until people reach their deductible, the plans pay only for specified preventive care, such as annual physicals and cancer screenings, and some care for chronic conditions.

Enrollees are on the hook for everything else, including most doctor visits and prescription drugs. In 2020, the minimum deductible for a plan that qualifies under federal rules for a tax-exempt health savings account is $1,400 for an individual and $2,800 for a family.

As their health savings account balances grew, “more people moved into the camp that could see the benefits” of the high-deductible strategy, Schmidt says. Still, not everyone wanted to be exposed to costs upfront, even if they ended up spending less overall.

“For some people, there remained a desire to pay more to simply have that peace of mind,” he says.

Digital River’s PPOs have deductibles of $400 and $900 for single coverage and $800 and $1,800 for families. The premiums are significantly more expensive than those of the high-deductible plans.

In the PPO plan with the $400/$800 deductible, the employee’s portion of the monthly premium ranges from $82.37 for single coverage to $356.46 for an employee plus two or more family members. The plan with the $2,700 deductible costs an employee $21.11 for single coverage, and the $5,300-deductible plan costs $160.29 for the employee plus at least two others.

But costs are more predictable in the PPO plan. Instead of owing the entire cost of a doctor visit or trip to the emergency room until they reach their annual deductible, people in the PPO plans generally owe set copayments or coinsurance charges for most types of care.

When Digital River introduced the PPO plans for this year, about 10% of employees moved from the high-deductible plans to the traditional plans.

Open enrollment for 2020 starts this fall, and the company is offering the same mix of traditional and high-deductible plans again for next year.

Adding PPOs to its roster of plans not only made employees happy but also made the company more competitive, Schmidt says. Two of Digital River’s biggest competitors offer only high-deductible plans, and the PPOs give Digital River an edge in attracting top talent, he believes.

According to the survey by the National Business Group on Health, employers that opted to add more choices to what they offered employees typically chose a traditional PPO plan. Members in these plans generally get the most generous coverage if they use providers in the plan’s network.

But if they go out of network, plans often cover that as well, though they pay a smaller proportion of the costs. For the most part, deductibles are lower than the federal minimum for qualified high-deductible plans.

Traditional plans like PPOs also give employers more flexibility to try different approaches to improve employees’ health, says Tracy Watts, a senior partner at benefits consultant Mercer.

“Some of the newer strategies that employers want to try just aren’t [health savings account] compatible,” says Watts. The firms might want to pay for care before the deductible is met, for example, or eliminate employee charges for certain services.

Examples of these strategies could include employer-subsidized telemedicine programs or direct primary care arrangements in which physicians are paid a monthly fee to provide care at no cost to the employee.

The “Cadillac tax,” a provision of the Affordable Care Act that would impose a 40% excise tax on the value of health plans that exceeded certain dollar thresholds, was a driving force behind the shift toward high-deductible plans. But the tax, originally supposed to take effect in 2018, has been pushed back to 2022. The House passed a bill repealing the tax in July, and there is a companion bill in the Senate.

It’s unclear what will happen, but employers appear to be taking the uncertainty in stride, says Brian Marcotte, president and CEO of the National Business Group on Health.

“I think employers don’t believe it’s going to happen, and that’s one of the reasons you’re seeing [more plan choices] introduced,” he says.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.