They Bring Medical Care To The Homeless And Build Relationships To Save Lives

Licensed practical nurse Stephanie Dotson measures Kent Beasley’s blood pressure in downtown Atlanta in September. Dotson is a member of the Mercy Care team that works to bring medical care to Atlanta residents who are homeless.

Bita Honarvar for WABE

hide caption

toggle caption

Bita Honarvar for WABE

Herman Ware sits at a small, wobbly table inside a large van that’s been converted into a mobile health clinic. The van is parked on a trash-strewn, dead-end street in downtown Atlanta where homeless residents congregate.

Ware is here for a seasonal flu shot.

“It might sting,” he says, thinking back on past shots.

Ware grimaces slightly as the nurse injects his upper arm.

After filling out some paperwork, he climbs down the van’s steps and walks back to a nearby homeless encampment where he’s been living. The small cluster of tents sits below an interstate overpass, next to a busy rail line.

Ware hasn’t paid much attention to his medical needs lately, which is pretty common among people living on the street. For those trying to find a hot meal or a place to sleep, health care can take a backseat.

“Street medicine” programs, like the outfit giving Ware his flu shot, aim to change that. Mercy Care, a health care nonprofit in Atlanta, operates a number of clinics throughout the city that mainly treat poor residents, and also has been sending teams of doctors, nurses and other health care providers into the city’s streets since 2013. The idea is to treat homeless people where they live.

“When we’re coming out here to talk to people, we’re on their turf,” says nurse practitioner Joy Fernandez de Narayan (right) in Atlanta. She and licensed practical nurse Stephanie Dotson (left), say showing patients respect is important in every setting.

Bita Honarvar for WABE

hide caption

toggle caption

Bita Honarvar for WABE

This public health strategy can now be found in dozens of cities in the U.S. and around the world, according to the Street Medicine Institute, which works to spread the practice.

Building relationships to give care

Giving shots and conducting exams outside the walls of a health clinic comes with unique challenges.

“When we’re coming out here to talk to people, we’re on their turf,” says nurse practitioner Joy Fernandez de Narayan, who runs Mercy Care’s Street Medicine program.

A big challenge is getting patients to accept help, whether it comes in the form of a vaccination or something simpler — like a bottle of water.

“We’ll sit down next to someone, like ‘Hey, how’s the weather treating you?’ ” she says. “And then kind of work our way into, like, ‘Oh, you mentioned you had a history of high blood pressure. Do you mind if we check your blood pressure?’ “

The outreach workers spend a lot of time forging relationships with homeless clients, and it can take several encounters to gain someone’s trust and get them to accept medical care.

Dotson gives a flu shot to Sopain Lawson, who lives in a homeless encampment under a bridge in downtown Atlanta. It can take several encounters to gain someone’s trust and get them to accept medical care, the health team finds.

Bita Honarvar for WABE

hide caption

toggle caption

Bita Honarvar for WABE

Their persistent encouragement was helpful for Sopain Lawson, who caught a debilitating foot fungus while living in the encampment.

“I couldn’t walk,” Lawson says. “I had to stay off my feet. And the crew, they took good care of my foot. They got me back.”

“This is what street medicine is about — going out into these areas where people are not going to seek attention until it’s an emergency,” says Matthew Reed, who’s been doing social work with the team for two years.

“We’re trying to avoid emergencies, but we’re also trying to build relationships.”

“Go to the people”

The street medicine team uses the trust they’ve built with patients to eventually connect them to other services, such as mental health counseling or housing.

Access to those services may not be readily available for many reasons, says Dr. Stephen Hwang, who studies health care and homelessness at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. Sometimes the obstacle — say, lacking enough money for a bus ticket — seems small, but is formidable.

“It may be difficult to get to a health care facility, and often there are challenges, especially in the U.S., where people don’t have health insurance,” Hwang adds.

Social worker Matthew Reed (right) talks with Lawson near her tent home in downtown Atlanta. Reed says,”This is what street medicine is about: going out into these areas where people are not going to seek attention until it’s an emergency.”

Bita Honarvar for WABE

hide caption

toggle caption

Bita Honarvar for WABE

Georgia is one of a handful of states that has not expanded Medicaid to all low-income adults, which means many of its poorest residents don’t have access to the government-sponsored health care program. But even if homeless people are able to get health coverage and make it to a hospital or clinic, they can run into other problems.

“There’s a lot of stigmatization of people who are experiencing homelessness,” Hwang says, “and so often these individuals will feel unwelcome when they do present to health care facilities.”

Street medicine programs are meant to break down those barriers, says Dr. Jim Withers. He’s medical director of the Street Medicine Institute and started making outreach visits to the homeless back in 1992, when he worked at a clinic in Pittsburgh.

“Health care likes people to come to it on its terms,” Withers says, while the central tenet of street medicine is, “Go to the people.”

Clinic patient Lawson (center) and nurse practitioner Fernandez de Narayan (right) share a hug outside the Mercy Care van, after the September check-in. “We’re trying to avoid emergencies, but we’re also trying to build relationships,” says social worker Reed (left).

Bita Honarvar for WABE

hide caption

toggle caption

Bita Honarvar for WABE

Help, with respect

Mercy Care in Atlanta spends about $900,000 a year on its street medicine program. In 2018, that sum paid for direct treatment for some 300 people, many of whom got services multiple times. Having clinics on the street can help relieve the care burden of nearby hospitals, which Withers says don’t have a great track record when it comes to treating the homeless.

“We’re not dealing with them well,” Withers admits, speaking on behalf of American health care in general. In traditional health settings, homeless patients do worse compared to other patients, he says. “They stay in the hospital longer. They have more complications.”

Those extra days and clinical complications mean additional costs for hospitals. One recent estimate cited in a legislative report on homelessness suggested that more than $60 million in medical costs for Atlanta’s homeless population were passed on to taxpayers.

Mercy Care says its program makes homeless people less likely to show up in local emergency rooms and healthier when they do — which saves money.

It’s past sundown when the street medicine team rolls up to their final stop: outside a church in Atlanta where homeless people often gather. A handful of people have settled down for the night on the sidewalk. Among them is Johnny Dunson, a frequent patient of the street medicine program.

Dunson says the Mercy Care staffers have a compassionate style that makes it easy to talk to them and ask for help.

“You gotta let someone know how you’re feeling,” Dunson says. “Understand me? Sometimes it can be like behavior, mental health. It’s not just me. It’s a lot of people that need some kind of assistance to do what you’re supposed to be doing, and they do a wonderful job.”

Along with the medical assistance, the staff at Mercy Care give every patient big doses of respect and dignity. When you’re living on the street, it can be hard to find either.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with WABE and Kaiser Health News.

America’s ‘Shame’: Medicaid Funding Slashed In U.S. Territories

Sandra King Young runs Medicaid in American Samoa, a U.S. territory that faces dramatic funding cuts to islanders’ health care unless Congress acts. “This is the United States’ shame in the islands,” she says.

Selena Simmons-Duffin/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Selena Simmons-Duffin/NPR

Right now, there are dozens of patients — U.S. citizens — in New Zealand hospitals who are fighting the clock. They have only a few weeks to recover and get home to the tiny island of American Samoa, a U.S. territory in the South Pacific.

“We have a cancer patient that is coming back in December,” says Sandra King Young, who runs the Medicaid program in American Samoa. “We can only give him six weeks of chemo, radiation and surgery. He has a good chance of survival if he has the full year of treatment, but not six weeks. The patient and family understand, and since they have no money, they have agreed to come back.”

The federal money to fully fund the Medicaid program in American Samoa and in all other U.S. territories is about to run out. As a consequence, the off-island referral program to treat conditions that the territory doesn’t have the local capacity or facilities to treat — the program that brought these patients to New Zealand — is getting shut down.

“It’s devastating for those people who need those lifesaving services,” King Young says. “People who need cancer treatment won’t get it. Children with rheumatic heart disease won’t get the heart surgeries that they need.”

All five of the U.S. territories affected — collectively home to more than 3 million Americans — are now desperately trying to figure out how to keep Medicaid running with only a fraction of the money they’ve had for the last several years. If Congress doesn’t increase the amount of designated money by the end of the year, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Guam say they would need to cut their Medicaid rolls in half; Puerto Rico says it would need to cut back dental and prescription drug services.

This is what people working on the issue have come to call the “Medicaid cliff.”

How did we get here?

When it comes to Medicaid, the federal government treats U.S. territories differently from how it treats states.

In U.S. states, the amount that the federal government contributes to Medicaid varies based on a formula in the law that relies on per capita income in each state. For instance, Alabama has a match rate of 72%; what this translates to is that for every dollar Alabama spends on Medicaid, the federal government contributes about $2.57 to the program.

But that’s not how it works in the territories, where even though the populations are all low income, the federal government’s match rate is set in statute at 55%. What this translates to is that for every dollar a U.S. territory spends on Medicaid, the federal government contributes $1.25.

The other significant difference is that the federal contribution to Medicaid in the territories is capped, with a set allotment of federal funds every year. Federal spending on Medicaid in states is not.

The low matching rate and the annual cap — that’s pretty much how it has always been for Medicaid in the territories, says Robin Rudowitz, who co-directs the Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “These particular provisions historically have always been part of how they have been financed,” she says.

Here’s how the territories found themselves peering over the “Medicaid cliff.” For the last few years, the territories have had billions of dollars more in federal funding to run their programs than their usual capped allotments. First, the Affordable Care Act provided a one-time grant of $7.3 billion (which kicked off in 2011) for the territories’ Medicaid programs. Then, in 2017, after two Category 5 hurricanes ravaged Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, an extra $4.9 billion designated for their Medicaid programs was added to the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act.

The Family Health Center Susana Centeno on remote Vieques island, part of Puerto Rico, was forced to close after it suffered damage from Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Xavier Garcia/Bloomberg/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Xavier Garcia/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Now, we’ve come to the cliff’s edge. Most of these two pots of money ran out at the end of September, with just a bit of funding from the ACA still available through the end of 2019.

That leaves, essentially, just the capped allotment of federal dollars for each of the territories — far less than what the territories have come to rely on to provide care to their Medicaid enrollees in recent years.

“The capped financing amounts were low and did not meet all of the needs of the population in the territories,” says Rudowitz. If the additional federal contributions are gone for good, she says, “given the share that they represent of the financing for Medicaid in these territories, it would mean major changes and reductions in care.”

The territories have known that this funding cliff was coming for years — the end to a major portion of the money was written into the ACA. Island health officials and care providers hoped Congress would have legislated a more permanent solution by now, but it hasn’t.

In recent months, Congress has passed continuing resolutions that have allowed the territories’ Medicaid programs to keep limping along. But without legislation that appropriates more money, the territories’ Medicaid programs all are in serious trouble.

The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, known as MACPAC, a nonpartisan government group that advises Congress on Medicaid policy, projected in July that all the territories will have budget shortfalls in 2020. When considered altogether, according to MACPAC’s report, their Medicaid programs will be more than $1 billion short.

This is why Medicaid directors in the U.S. territories are all sounding the alarm. King Young, of American Samoa, points to news coverage as far back as the 1960s that described her island as “America’s Shame in the South Seas” because of rampant pollution and neglect.

“Right now, this is the United States’ shame in the islands,” she says. “Tell me if that’s acceptable in the United States, to stand by and say, ‘Oh, sorry, we can’t give you that stent or that pacemaker, so it’s likely that you’ll have a stroke or heart attack and — that’s it.’ That’s what it means not to have enough Medicaid funding for the territories.”

“Full-court press” in Congress

The territories have been lobbying Congress, urging members to appropriate more funds for their Medicaid programs so health officials on the islands can avoid these hard choices — between, for instance, keeping a hospital going and paying for a patient’s cancer treatment.

Each territory has a nonvoting delegate in Congress. Puerto Rico also sent an additional delegation from the island last week to make the case to lawmakers that something must be done to stave off disaster.

“I would say that we’ve been doing a full-court press this entire calendar year,” says Jennifer Storipan, executive director of the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration. “Gov. [Wanda] Vázquez has said that Medicaid funding is her highest priority for the island right now.”

A bill to temporarily increase funding to the territories’ Medicaid programs was passed by the House Energy and Commerce Committee in July but has yet to make it to the floor for a vote. It would greatly increase the federal match rate for Medicaid in all the territories and allocate a bonus $3 billion a year — but only for the next four years. There is no companion bill in the Senate.

“We’re in active negotiations with the Senate, but there is some opposition to our bill in the Senate,” says Rep. Darren Soto, D-Fla., who introduced the House legislation with Rep. Gus Bilirakis, R-Fla. Both represent districts in central Florida that have huge Puerto Rican populations, and Soto is of Puerto Rican descent. In the House, the bill has bipartisan support.

Opponents of the bill in the Senate say they worry that the billions of dollars that the territories are requesting could be misspent. Some senators have raised particular concerns about Puerto Rico. During a recent corruption probe, a Puerto Rican Medicaid official was arrested — that news emerged just a few days before a committee hearing on the territories’ Medicaid bill in July.

“So that didn’t help,” Soto says. Integrity provisions were added to the House bill, he says, specifically addressing concerns about Puerto Rico. “We do need to take it seriously and make sure that tax dollars are safeguarded,” he says, but adds, “There have been fraud instances in many states too, and we don’t take away their Medicaid funding.”

Some congressional Republicans note that the funding cliff was created by the Affordable Care Act, which gave extra funding to the territories for a limited time. In a letter to Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar in July, several Republican members of the Senate Finance Committee raised concerns about Puerto Rico’s Medicaid spending.

“We are again confronting proposals for what amounts to another extension of boosted funding with no permanence or certainty and without any resolution of the Medicaid funding cliff constructed as part of the ACA,” they wrote.

“It is true: Giving these additional funds with a set expiration date, the legislation itself did create the cliff,” acknowledges the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Rudowitz. However, she says, Congress now should consider “the implications of letting that cliff happen and what that means to the health care systems in these territories.”

Planning for the worst

Medicaid program administrators from each of the territories gathered in an impromptu meeting outside the annual Medicaid directors conference last week. They have spent a lot of time together in Washington recently, testifying before congressional committees about the Medicaid funding crisis as it approaches.

“We were here in May. We were here in June,” Michal Rhymer-Browne, assistant commissioner with the Virgin Islands’ Department of Human Services, told NPR that day. “We pleaded. We shared ourselves — everything that we could.”

Despite their pleas, Congress has yet to act.

There are three options for managing a slashed budget for a program like Medicaid: reduce the size of payments to providers, cut the rolls or cover fewer services. All the territories say there’s no way to go lower on provider payments — Puerto Rico’s struggle with provider flight because of low pay is well known. So cutting the rolls and covered services is where the programs would need to find cuts, representatives of the territories say.

“Guam and [the Northern Mariana Islands] are about to topple over the cliff,” Rhymer-Browne says. “And for the Virgin Islands, we are nearing the cliff and seeing the bottom right now.”

Many of the territories would like to make improvements in the care they provide — invest in better facilities, recruit great health care providers, improve preventive care. All of that comes with upfront costs, they say, and they’ve had so much budget uncertainty that it has been impossible to move forward with those kinds of projects.

Right now, they’re just trying to keep the lights on.

“The urgency is here for us to let our congressional members know — even going to January is extremely dangerous,” Rhymer-Browne says. “It’s already catastrophic for our territories. We really need them to make a move.”

Want New Taxes To Pay For Health Care? Lessons From The Affordable Care Act

A demonstrator celebrated outside the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015 after the court voted to uphold key tax subsidies that are part of the Affordable Care Act. But federal taxes and other measures designed to pay for the health care the ACA provides have not fared as well.

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images

It was a moment of genuine bipartisanship at the House Ways and Means Committee in October, as Democratic and Republican sponsors alike praised a bill called the “Restoring Access to Medication Act of 2019.”

The bill, approved by the panel on a voice vote, would allow consumers to use their tax-free flexible spending accounts or health savings accounts to pay for over-the-counter medications and women’s menstrual products.

Assuming the measure ultimately finds its way into law, it would also represent the latest piece of the Affordable Care Act’s financing to be undone.

Over-the-counter medication had been eligible to be considered a pretax expenditure in this way, before the ACA. But that eligibility was eliminated as part of a long list of new taxes and other measures that were designed to generate revenue to help pay for expanding health coverage to more people — a roughly $1 trillion cost of the health law over its first 10 years.

“It is paid for. It is fiscally responsible,” said President Barack Obama as he signed the ACA into law in 2010.

But not so much anymore. Many of the taxes and other provisions aimed at paying for that expanded health coverage “have been eliminated, delayed or are in jeopardy,” says Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonpartisan budget watchdog group. “All this stuff, it turns out, is very unpopular.”

The first piece of financing to disappear happened before most of the law even took effect. In 2011, Congress repealed a requirement that small businesses report to the IRS any payment of more than $600 to a vendor. The idea was that if more such payments were reported to taxing authorities, more taxes due on that income would actually get paid.

But small businesses complained — loudly — that the new paperwork requirement would be excessive, and Congress (and Obama) eventually agreed. The change alone eliminated an estimated $17 billion in ACA financing over 10 years.

Next, in 2015, Congress delayed (for the first time) the “Cadillac tax,” a 40% tax on the most generous employer health plans; one goal of that tax had been to curb excessive use of medical services.

That congressional delay came after intense lobbying by a coalition of business, labor and patient advocacy groups that banded together in a group called the Alliance to Fight the 40. It first got Congress to delay the Cadillac tax’s implementation from 2018 to 2020, then further pushed that date to 2022. And this past summer the House voted overwhelmingly to altogether eliminate the tax, which had been estimated to raise nearly $200 billion over the next decade.

Also on ice, thanks to that 2018 bill, are levies that were supposed to be paid by medical-device makers and health insurance companies, originally worth a combined $80 billion in financing during the law’s first decade.

Yet another — albeit fairly small — source of financing for the law went away in the 2017 GOP tax bill, which zeroed out the tax penalty for failing to have health insurance. The penalty raised $4 billion in 2018, the last year it was in effect.

Now it should be pointed out that the two ACA taxes that generate the most revenue are still on the books and collecting money. They are aimed at people with high incomes (more than $200,000 for individuals and $250,000 for couples) and were estimated to bring in more than $200 billion from 2010 to 2019. The measures, which don’t deal directly with services or provisions of the ACA, raise Medicare taxes on people at those higher incomes and increase taxes on unearned income.

The durability of those two taxes does not surprise Goldwein. Some are “unpopular to repeal,” he says, like “a tax on the rich that funds Medicare.”

What Goldwein does find surprising, though, is how durable some of the ACA’s other financing measures — reductions in spending — have been. For example, the health law, somewhat controversially, reduced Medicare payments to hospitals, insurance companies and a broad array of other health providers.

“The Medicare cuts have been for the most part surprisingly sustainable politically,” Goldwein says. Even when the GOP took over the House in 2011, its budget maintained the reductions from the ACA. So did the 2017 GOP “repeal and replace” proposal.

On the other hand, the appointed board of experts that was to rein in future Medicare spending, the “Independent Payment Advisory Board,” never got off the ground. Congress formally repealed it in 2018.

So what does this all mean? The past decade has shown that it has been relatively easy to make hard-won tax increases go away, suggesting that interest groups — particularly health industry groups representing drugmakers, insurers and hospitals — still wield a lot of power on Capitol Hill.

“Right now, everyone wants to cancel a 3% tax on the health insurance industry,” he says, referring to the current efforts of a major ad campaign by a coalition of small-business owners and insurance groups to get Congress to delay or cancel that ACA-linked tax.

Given how much money from health insurers is going into fighting that tax, he says, how likely is it that Congress — even one controlled by Democrats — would really “cancel the whole industry” by passing a “Medicare for All” bill?

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Trump Administration’s Efforts To Ban Most Flavored Vaping Products Have Stalled Out

The White House is apparently backpedaling on its plan to ban most flavors in vaping products. The proposed FDA rule is unpopular with vape shop owners, and that’s creating political blowback.

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

The Trump administration’s efforts to ban most flavored vaping products have stalled out. The president announced two months ago that he would do something to address the youth vaping epidemic. A plan was supposed to have been announced in a matter of weeks. NPR science correspondent Richard Harris explains what happened instead.

RICHARD HARRIS, BYLINE: When President Trump said he was endorsing a Food and Drug Administration proposal to ban most flavored vaping products, he acknowledged there were some economic consequences.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Vaping has become a very big business, as I understand it – like, a giant business in a very short period of time. But we can’t allow people to get sick, and we can’t have our youth be so affected.

HARRIS: The policy proposal hit just as health officials were investigating lung injuries and deaths among people who vaped. Scientists now say that’s primarily from vaping dubious marijuana products. But Paul Billings at the American Lung Association was also focused on the role that flavored e-cigarettes played in teen nicotine addiction.

PAUL BILLINGS: We were very optimistic, encouraged when the president announced that he wanted to clear the markets of all flavored e-cigarettes that play such an important role in addicting millions of kids to these products.

HARRIS: That optimism started to fade after the policy did not appear as promised in the following weeks.

BILLINGS: It stretched into months. A package was sent to the White House for review, and then it cleared. And then everything stopped on November 5.

HARRIS: The Washington Post reports that’s when the president’s political staff advised him not to sign off on the new rules.

Paul Blair at the conservative group Americans for Tax Reform was part of the push against the new rules.

PAUL BLAIR: Look. There are legitimate concerns about teens experimenting with these products, but running towards the 1920s in terms of prohibition is a vote-losing issue.

HARRIS: That message hit the airwaves of Fox News, which ran commercials like this one.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: If you enact a flavor ban, this will cost you the election.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: I vape, and I vote.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: Vapor Technology Association is responsible for the content of this advertising.

HARRIS: And advocates assert that a vaping flavor ban could tilt the election in close states against Trump. Blair’s organization polled people who vape in swing states like Michigan a few years back.

BLAIR: Three out of 4 of these adult consumers are single-issue voters.

HARRIS: And Blair says that issue is access to vaping, including flavored products. Some also argue that getting rid of flavored vaping products could drive people back to smoking cigarettes, which are the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. On top of that, Blair says the industry itself provides 150,000 jobs through vape shops and manufacturers.

BLAIR: It’d be a pretty significant hit in an election year for a guy that’s focused on deregulations, spurring economic growth and not killing jobs.

HARRIS: Big Tobacco is also part of the story, says Paul Billings at the American Lung Association.

BILLINGS: The largest tobacco companies in the world, like Altria and Reynolds, are major players in the e-cigarette business, along with these vape shops.

HARRIS: And these forces appear to have won out over the public health advocates. So Billings says the lead could well shift to states, counties and cities.

BILLINGS: And so we fully expect, irrespective of what the administration does or does not do, that states and localities will continue to move forward.

HARRIS: A White House spokesman says the new rules haven’t been killed, but it’s not clear what, if anything, will survive this process.

Richard Harris, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF SMALL BLACK SONG, “SOPHIE”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

A Young Immigrant Has Mental Illness, And That’s Raising His Risk of Being Deported

José’s son, who has schizophrenia, recently got into a fight that resulted in a broken window — an out-of-control moment from his struggle with mental illness. And it could increase his chances of deportation to a country where mental health care is even more elusive.

Hokyoung Kim for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Hokyoung Kim for NPR

When José moved his family to the United States from Mexico nearly two decades ago, he had hopes of giving his children a better life.

But now he worries about the future of his 21-year-old-son, who has lived in central Illinois since he was a toddler. José’s son has a criminal record, which could make him a target for deportation officials. We’re not using the son’s name because of those risks, and are using the father’s middle name, José, because both men are in the U.S. without permission.

José’s son was diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder last year and has faced barriers to getting affordable treatment, in part because he doesn’t have legal status. His untreated condition has led to scrapes with the law.

Mental health advocates say many people with untreated mental illness run the risk of cycling in and out of the criminal justice system, and the situation is particularly fraught for those without legal status.

“If he gets deported he’d practically be lost in Mexico, because he doesn’t know Mexico,” says José, speaking through an interpreter. “I brought him here very young and, with his illness, where is he going to go? He’s likely to end up on the street.”

Legal troubles

José’s son has spent several weeks in jail and numerous days in court over the past year.

On the most recent occasion, the young man sat nervously in the front row of a courtroom in the Champaign County courthouse. Wearing a white button-down shirt and dress pants, his hair parted neatly, he stared at the floor while he waited for the judge to enter.

That day, he pleaded guilty to a criminal charge of property damage. The incident took place at his parents’ house earlier that year. He had gotten into a fight with his brother-in-law and broke a window. His father says it was yet another out-of-control moment from his son’s recent struggles with mental illness.

Before beginning proceedings, the judge read a warning aloud — something that is now standard practice to make sure noncitizens are aware that they could face deportation (or be denied citizenship or re-entry to the U.S.) if they plead guilty in court.

The young man received 12 months’ probation.

After the hearing, he agreed to an interview.

Just a couple of years ago, he says, his life was good: He was living on his own, working, and taking classes at community college. But all that changed when he started hearing voices and began struggling to keep his grip on reality. He withdrew from his friends and family, including his dad.

One time, he began driving erratically, thinking his car was telling him what to do. A month after that episode, he started having urges to kill himself and sometimes felt like hurting others.

In 2018, he was hospitalized twice, and finally got diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

José says that during this time, his son — who had always been respectful and kind — grew increasingly argumentative and even threatened to hurt his parents. The psychiatric hospitalizations didn’t seem to make a difference.

“He asked us for help, but we didn’t know how to help him,” José says. “He’d say, ‘Dad, I feel like I’m going crazy.’ “

José’s son says he met with a therapist a few times and was taking the medication he was prescribed in the hospital. He was also using marijuana to cope, he says.

The prescribed medication helped, he says, but without insurance, he couldn’t afford to pay the $180 monthly cost. When he stopped the meds, he struggled, and continued getting into trouble with the police.

Undocumented and uninsured

For people who are both undocumented and living with a mental illness, the situation is “particularly excruciating,” says Carrie Chapman, an attorney and advocate with the Legal Council for Health Justice in Chicago, who represents many clients like José’s son.

“If you have a mental illness that makes it difficult for you to control behaviors, you can end up in the criminal justice system,” Chapman says.

People with mental illness make up only a small percentage of violent offenders — they are actually more likely, compared to the general population, to be a victim of a violent crime.

Chapman says the stakes are extremely high when people without legal status enter the criminal justice system: they risk getting deported to a country where they may not speak the language, or where it’s even more difficult to obtain quality mental health care.

“It could be a death sentence for them there,” Chapman says. “It’s an incredible crisis, that such a vulnerable young person with serious mental illness falls through the cracks.”

An estimated 4.1 million adults under the age of 65 who live in the U.S. are ineligible for Medicaid or marketplace coverage under the Affordable Care Act because of their immigration status, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Among them are those who are undocumented and other immigrants who otherwise do not fall into one of the federal categories as lawfully in the U.S. People who are protected from deportation through the federal government’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, or DACA, also are ineligible for coverage under those programs.

For many people in all those groups, affordable health care is out of reach.

Some states have opened up access to Medicaid to undocumented children, including Illinois, California, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, Washington and the District of Columbia, according to the National State Conference of Legislatures. But they lose that coverage at age 19, except in California, which recently expanded eligibility through age 25.

For those who can’t get access to affordable health insurance because of their undocumented status, medical care is largely limited to emergency services and treatments covered by charity care or provided by community health centers.

It’s unclear how many people have been deported because of issues linked to mental illness; good records are not available, says Talia Inlender, an attorney for immigrants’ rights with the Los Angeles-based pro bono law firm Public Counsel. But estimates from the ACLU suggest that tens of thousands of immigrants deported each year have a mental disability.

Inlender, who represents people who have mental health disabilities in deportation hearings, says when the lack of access to community-based treatment eventually leads to a person being detained in an immigration facility, that person risks further deterioration because many facilities are not equipped to provide the needed care.

On top of that, she says, immigrants facing deportation in most states don’t generally have a right to public counsel during the removal proceedings and have to represent themselves. Inlender points out that an immigrant with a mental disability could be particularly vulnerable without the help of a lawyer.

(Following a class-action lawsuit, the states of Washington, California and Arizona did establish a right to counsel for immigrants with mental illness facing deportation. For those in other states, there’s a federal program that tries to provide the same right to counsel, but it’s only for detained immigrants who have been properly screened.)

Medicaid for more people?

Chapman and other advocates for immigrants’ rights say expanding Medicaid to cover everyone who otherwise qualifies — regardless of legal status — and creating a broader pathway to U.S. citizenship would be good first steps toward helping people like José’s son.

“Everything else is kind of a ‘spit and duct tape’ attempt by families and advocates to get somebody what they need,” Chapman says.

Critics of the push to expand Medicaid to cover more undocumented people object to the costs, and argue that the money should be spent, instead, on those living in the country legally. (California’s move to expand Medicaid through age 25 will cost the state around $98 million, according to some estimates.)

As for José’s son, he recently found a pharmacy that offers a cheaper version of the prescription drug he needs to treat his mental health condition — so he’s back on medication and feeling better.

He now works as a landscaper and hopes to get back to college someday to study business. But he fears his criminal record could stand in the way of those goals, and he’s aware that his history makes him a target for immigration sweeps.

José says his greatest fear is that his son will end up back in Mexico — away from family and friends, in a country he knows little about.

“There are thousands of people going through these issues … and they’re in the same situation,” José says. “They’re in the dark, not knowing what to do, where to go, or who to ask for help.”

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with Side Effects Public Media, Illinois Public Media and Kaiser Health News. Christine Herman is a recipient of a Rosalynn Carter fellowship for mental health journalism. Follow her on Twitter: @CTHerman

Trump Wants Insurers and Hospitals To Show Real Prices To Patients

One rule announced by the Trump administration Friday puts pressure on hospitals to reveal what they charge insurers for procedures and services. Critics say the penalty for not following the rule isn’t stiff enough to be a an effective deterrent.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Updated at 3:10 p.m. ET

President Trump has made price transparency a centerpiece of his health care agenda. Friday he announced two regulatory changes in a bid to provide more easy-to-read price information to patients.

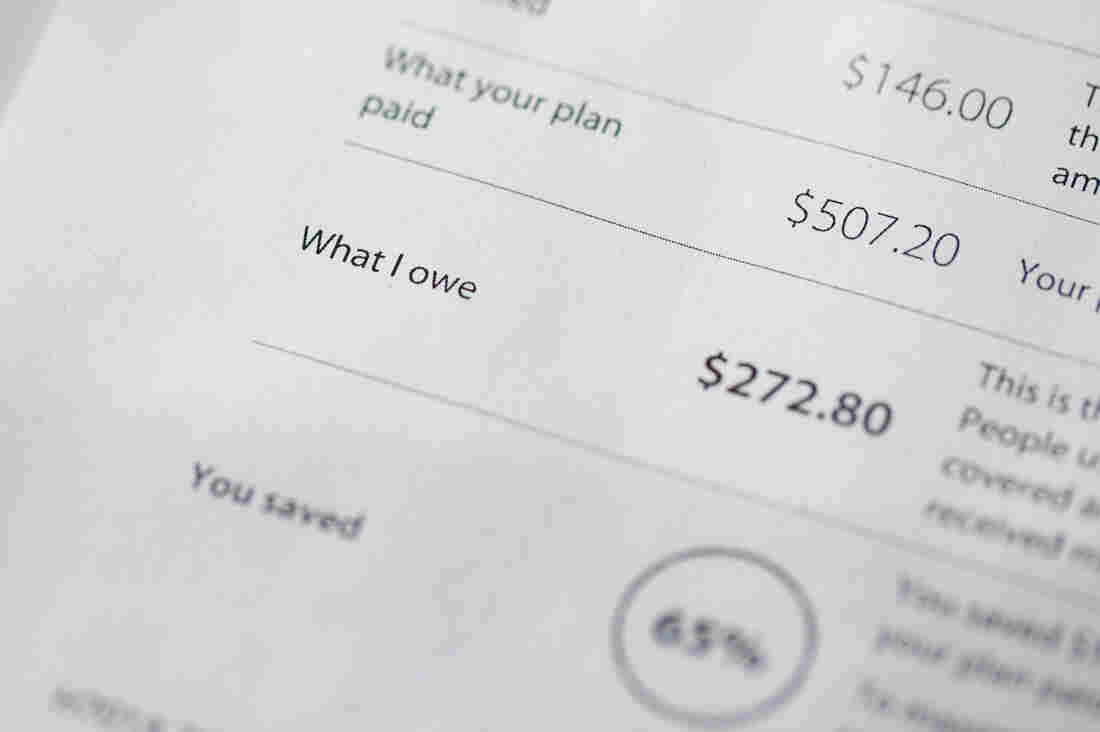

The first effort targets hospitals, finalizing a rule that requires them to display their secret, negotiated rates to patients starting in January 2021. The second is a proposal to make insurance companies show patients their expected out-of-pocket costs through an online tool. That proposed rule is subject to 60 days of public comment, and it’s unclear when it would go into effect.

“Our goal is to give patients the knowledge they need about the real price of health care services,” said Trump. “They’ll be able to check them, compare them, go to different locations, so they can shop for the highest-quality care at the lowest cost.”

Administration officials heralded both rules as historic and transformative to the health care system.

“Under the status quo, health care prices are about as clear as mud to patients,” said Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma in a written statement. “Today’s rules usher in a new era that upends the status quo to empower patients and put them first.”

As NPR has reported, hospitals are currently required to post their “list prices” online, but that information has been very hard to use and doesn’t tell consumers much about what they are likely to pay. The new rule makes hospitals show what they really pay for services — not the list prices — and requires them to make that information easy to read and easy to access.

“I don’t know if the hospitals are going to like me too much anymore with this,” Trump said in a White House news conference Friday afternoon. “That’s OK.” He later added, “We’re stopping American patients from just getting — pure and simple, two words, very simple words — ripped off. Because they’ve been ripped off for years. For a lot of years.”

The second rule Trump announced Friday (which is a proposed rule, still subject to public comments before being finalized) affects insurance companies. It would essentially make insurers give patients their “explanation of benefits” upfront. It would require insurers to explain how much a service would cost, how much your plan would pay and how much you would owe — before the service is performed. The idea is that patients could use that information to shop around ahead of time for a better deal — assuming a better deal can be found, and the service isn’t a medical emergency.

Certainly these rules would give patients more information than they currently have. The other promise of these rules — that they will bring down health care costs — is more of an open question.

In public comments for the hospital rule, hospitals argued that having to make their negotiated rates public would backfire — if a hospital is charging less than another one nearby, it could theoretically raise its price to more closely match its competitor’s.

Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar dismissed that argument on a call with reporters Friday morning.

“This is a canard,” he said. “Point me to one sector of the American economy where the disclosure of having price information in a competitive marketplace actually leads to higher prices as opposed to lower prices.”

Larry Levitt, executive vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, pointed out on Twitter that the penalty for hospitals that defy Trump’s transparency rule was “quite weak.”

“A maximum fine of $300 per day,” he wrote. “The technical term for that is ‘chump change.’ I wonder how many hospitals will just pay the fine.”

There’s also an open question about whether these rules will survive legal challenges. Another Trump administration proposal to show drug list prices in television ads was blocked in the courts.

“We may face litigation, but we feel we’re on a very sound legal footing for what we’re asking,” Azar told reporters.

Novelist Doctor Skewers Corporate Medicine In ‘Man’s 4th Best Hospital’

“The profession we love has been taken over,” psychiatrist and novelist Samuel Shem tells NPR, “with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.”

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

“Don’t read The House of God,” one of my professors told me in my first year of medical school.

He was talking about Samuel Shem’s 1978 novel about medical residency, an infamous book whose legacy still looms large in academic medicine. Shem — the pen name of psychiatrist Stephen Bergman — wrote it about his training at Harvard’s Beth Israel Hospital (which ultimately became Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) in Boston.

My professor told me not to read it, I imagine, because it’s a deeply cynical book and perhaps he hoped to preserve my idealism. Even though it has been more than 40 years since its publication, doctors today still debate whether it deserves its place in the canon of medical literature.

The novel follows Dr. Roy Basch, a fictional version of Shem, and his fellow residents during the first year of their medical training. They learn to deflect responsibility for challenging patients, put lies in their patients’ medical records and conduct romantic affairs with the nursing staff.

Basch’s friends even coin a term that is still in wide use in real hospitals today: Elderly patients with a long list of chronic conditions are still sometimes called “gomers,” which stands for “Get Out of My Emergency Room.”

Like any banned book, The House of God piqued my curiosity, and I finally read it this past year. I’m a family physician and a little over a year out of training, and I read it at the perfect time.

I got all the inside jokes about residency — and many were laugh-out-loud funny — but I am now far enough removed that the cynicism felt like satire rather than reality.

The House of God also felt dated. Basch and his cohort — who were, notably, all men, although not all white — didn’t have electronic medical records or hospital mergers to contend with. They wrote their notes about patients in paper charts. And it was almost quaint how much time the doctors spent chatting with patients in their hospital rooms.

It couldn’t be more different from my experience as a resident in the 21st century, which was deeply influenced by technology. There’s research to suggest that my cohort of medical residents spent about a third of our working hours looking at a computer — 112 of about 320 working hours a month.

In The House of God, set several decades before I set foot in a hospital, where were the smartphones? Where was the talk of RVUs — relative value units, a tool used by Medicare to pay for different medical services — or the push to squeeze more patients into each day?

That’s where Shem’s new book comes in. Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the fictional sequel to The House of God, and Basch and the gang are back together to fight against corporate medicine. This time the novel is set in a present-day academic medical center, and almost every doctor-patient interaction has been corrupted by greed and distracting technology.

Basch’s team has added a few more female physicians to its ranks, and together they battle a behemoth of an electronic medical record system. The hospital administrators in Shem’s latest book pressure the doctors to spend less time with every patient.

If The House of God is the great medical novel of the generation of physicians who came before me, perhaps Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the book for my cohort. It still has Shem’s zany brand of humor, but it also takes a hard look at forces that threaten the integrity of modern health care.

I spoke with Shem about Man’s 4th Best Hospital (which hit bookstores this week) and about his hopes for the future of medicine.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The protagonist in Man’s 4th Best Hospital, Dr. Roy Basch, doesn’t have a smartphone. I hear you don’t either. Why not?

If I had a smartphone, I would not be able to write any other novels. I have a bit of an addictive personality. I’d just be in it all the time. … I’ve got a flip phone. You can text me, but it has to be in the form of a question. I have this alphabetical keyboard. You either get an “OK” or an “N-O.”

A big theme in the novel is that technology has the potential to undermine the doctor-patient relationship. What made you want to focus on this?

I got a call out of the blue five years ago from NYU medical school. They said, “Do you want to be a professor at NYU med?” And I said, “What? Why?” And they said, “We want you to teach.” When I first got there, because I had been out of medicine [and hadn’t practiced since 1994], I figured, “Oh, I’ll look into what’s going on.” And I spent a night at Bellevue.

On the one hand, it’s absolutely amazing what medicine can do now. I remember I had a patient in The House of God [in the 1970s] with multiple myeloma. And that was a death sentence. We came in; we did the biopsy. He was dead. He was going to be dead. And that was that. Now it’s curable.

At Bellevue, I saw the magnificence of modern medicine. But like someone from Mars coming in and looking at this fresh, I immediately grasped the issues of money and effects of screens — computers’ and smartphones’.

And it just blew me away. It blew me away: the grandeur of medicine now and the horrific things that are happening to people who are really, sincerely, with love, trying to practice it. They are crunched, by being at the mercy of the financially focused system and technology.

In Man’s 4th Best Hospital, there’s a fair amount of nostalgia for the “good old days” of medicine in the 1960s and 1970s, before electronic medical records. What was better in that era?

If you ask doctors of my generation, “Why did you go into medicine?” they say, “I love the work. I really want to do good for people. I’m respected in the community, and I’ll make enough money.” Now: … “I want to have a good lifestyle.” Because you can’t make a ton of money in medicine anymore. You don’t have the respect of your community anymore. They may not even know much about you in a community because of all these [hospital] consolidations.

Do you think anything in medicine has gotten better?

The danger of isolation and the danger of being in a hierarchical system — students now are protected a lot more from that. When I was in training, interns were just so incredibly exhausted that they started doing really stupid things to themselves and patients. The atmosphere of training, by and large in most specialties, is much better.

You wrote an essay in 2002 titled “Fiction as Resistance,” about the power of novels to help make political and cultural change. What kind of resistance today can help fix American health care?

When somebody falls down, up onstage at a theater, do you ever hear the call go out, “Is there an insurance executive in the house?” No. If there are no doctors practicing medicine, there’s no health care. Doctors have to do something they have almost never done: They have to stick together. We have to stick together for what we want, in terms of the kind of health care we want to deliver, and to free ourselves from this computer mess that is driving everybody crazy, literally crazy.

Doctors don’t have a great track record of political activism, and only about half of physicians voted in recent general elections. What do you think might inspire more doctors to speak out?

Look at the difference between nurses and doctors. Nurses have great unions, powerful unions. They almost always win.

Doctors have never, ever formed anything like what the nurses have in terms of groups or unions. And that’s a big problem. So doctors somehow have to find a way — and under pressure, we might — to stick together. Doctors have to make an alliance with nurses, and other health care workers, and patients. That’s a solid group of people representing themselves in terms of what we think is good health care.

The profession we love has been taken over, with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.

Health care is a big issue for the upcoming election. What kind of changes are you hoping we’ll see?

There will be some kind of national health care system within five years. … You know, America thinks it has to invent things all over again all the time. Look at Australia. Look at France. Look at Canada. They have national systems, and they also have private insurance. Don’t get rid of insurance.

The two biggest subjects for the election are health care and health care. … The bad news is, it’s really hard to get done. The good news is, I think it’s inevitable. The good news is, it’s so bad it can’t go on.

One of the major criticisms of The House of God is that it’s sexist. It seems like your hero, Dr. Basch, has gotten a little more enlightened by the time of Man’s 4th Best Hospital. Does this reflect a change you’ve also experienced personally?

I was roundly criticized for the way women were seen in The House of God.

I remember the first rotation I had as a medical student at Harvard med was at Beth Israel, doing surgery. It got to be late at night, and I was trailing the surgeon around, and he went into the on-call room. There was a bunk bed there, and he started getting ready to go to bed. And I said, “Well, I’ll take the top bunk.” And he said, “You can’t sleep here.” So I left, and in walked a nurse. I was shocked.

Things have changed, and I am very, very glad. I don’t know if it seems conscious — I was very pleased to have total gender equity in the Fat Man Clinic [where the characters in Man’s 4th Best Hospital work] by the end of the book.

What made you feel like it was time to update The House of God?

I write to point out injustice as I see it, to resist injustice, and the danger of isolation, and the healing power of good connection. … We can help our patients to get better — but nobody has time to make the human connection to go along with getting them better.

Mara Gordon is a family physician in Camden, N.J., and a contributor to NPR. You can follow her on Twitter: @MaraGordonMD.

When Countries Get Wealthier, Kids Can Lose Out On Vaccines

Mothers and their babies in Nigeria wait at a health center that provides vaccinations against polio. Vaccination rates lag in the middle-income country.

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

You’d think that as a poor country grows wealthier, more of its children would get vaccinated for preventable diseases such as polio, measles and pneumonia.

But a review published in Nature this month offers a different perspective.

“The countries that are really poor get a lot of support for the vaccinations. The countries that are really rich can afford to pay for the vaccines anyway,” says Beate Kampmann, director of the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and author of the review.

But, she says, “the middle-income countries are in a tricky situation because they don’t qualify for support, yet they don’t necessarily have the financial resources and stability to purchase the vaccines.”

Adrien de Chaisemartin, director of strategy and performance at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, agrees: “More and more vulnerable populations live in middle-income countries.” Gavi, an international nonprofit that helps buy and distribute vaccines, projects that 70% of the world’s under-immunized children will live in middle-income countries by 2030.

Brazil, India, Indonesia and Nigeria were among the 10 countries with the most children who lacked basic vaccinations in 2018 — for example, shots to prevent diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis by age 1. Each of those countries meets the World Bank’s definition of a middle-income country: an average annual income (known as the gross national income, or GNI, per capita) between $1,026 and $12,375. In Nigeria alone, 3 million kids are undervaccinated. That’s 15% of the world’s total of children who lack key vaccinations.

By contrast, vaccination rates can be high in poor countries, according to global health researchers, who say that Gavi has boosted the numbers. Rwanda, for instance, despite having a GNI of $780 per person, now has a near-universal coverage rate for childhood vaccines, on par with some of the wealthiest countries.

But in general, once a country reaches a GNI per capita threshold over $1,580 for three years, support from Gavi tapers off. And despite their improved fortunes, countries don’t always choose to fund childhood vaccines.

Angola is among the middle-income countries with the lowest vaccination rates. Diamonds and oil have helped propel the country out of low-income status, and its president is a billionaire. Yet an estimated 30% to 40% of children there did not receive basic vaccines in 2018.

The lag in vaccination rates is caused by any number of reasons. “There’s a whole list of middle-income countries, and they’re not all the same,” says Kampmann.

For example, Sam Agbo, former chief of child survival and development for UNICEF Angola, says Angola’s leadership does not fully fund immunization programs. Agbo blames a political system that he says is mired in corruption, financial mismanagement and lots of debt. So it’s hard to increase the health care budget. “Primary health care is not sexy,” he says. “People are interested in building hospitals and specialized centers rather than investing in preventive care.”

Gavi’s de Chaisemartin groups Angola with other resource-rich but corruption-plagued countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea and East Timor. “These are countries where the GNI is relatively high because of their oil resources, for the most part, but that doesn’t translate into a stronger health system,” says de Chaisemartin.

Then there’s the matter of cost. Countries that buy vaccines on the open market might pay over $100 a shot.

Public attitudes also play a role. In Brazil, which is on the high end of the middle-income spectrum, an immunization program that once outperformed World Health Organization recommendations has been declining for three years. Jorge Kalil Filho, an immunology professor at the University of Sao Paulo, says public inattention and anti-vaccine campaigns, popular on social media, are undermining progress.

De Chaisemartin says the global health community needs to adjust to an unprecedented global economic shift. “Fifteen years ago, the world was divided between poor countries, where most poor people were living, and high-income countries,” says de Chaisemartin. “Now you have a lot of middle-income countries with very poor and vulnerable populations.”

The Controversy Around Virginity Testing

NPR’s Michel Martin talks with Sophia Jones, senior editor for The Fuller Project, about the controversy surrounding virginity testing.

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

We’re going to turn now to a story that made all kinds of waves on social media last week. And here is where I feel I should say we’re going to get into a level of detail about anatomy that some may find uncomfortable.

The story is this. The rapper and producer T.I. said in an interview with the host of the “Ladies Like Us” podcast that he has been taking his now 18-year-old daughter to her annual visit with her gynecologist every year to confirm that she’s not sexually active. How would he confirm this? By insisting that the doctor determine whether her hymen is intact. It’s a practice known as virginity testing, and it’s a practice that has been widely condemned by medical professionals around the world, including the World Health Organization, as unscientific, medically meaningless and even abusive.

We wanted to learn more about this, including how widespread this practice remains, so we’ve called Sophia Jones. She’s a senior editor and journalist with the Fuller Project. That’s a nonprofit journalist organization reporting on global issues affecting women. She’s written widely about this. And she’s with us now from Istanbul, Turkey.

Sophia Jones, thank you so much for talking with us.

SOPHIA JONES: Thank you for having me.

MARTIN: So, first of all, how widespread is this practice?

JONES: So that’s a good question, and most people don’t really know. So I started reporting on this about a year ago, when I was planning a trip to Afghanistan, where – virginity testing is widespread there. And I started asking researchers and physicians in the United States if they had ever heard of this happening in the U.S. And so I started asking that question – how common is this? Have you heard of this?

And it took a few months for people to really start to get back to me and to talk about this. They said that they were routinely asked to perform hymen exams to determine virginity, which is not scientific, and that they had occasionally actually performed the exams themselves or they had heard of colleagues performing them.

MARTIN: And, just to clarify for people who may not know, what exactly is the hymen? What function does it serve? Does it serve any biological function that we know?

JONES: The hymen is a thin piece of mucous membrane that can be found near the entrance of the vagina. It has no proven purpose whatsoever. Doctors and experts really don’t know why the hymen exists. Some baby girls are born without a hymen. Many are born with a hymen. But it comes in many different shapes and sizes.

MARTIN: What in your reporting have you indicated has been the consequence of these kinds of tests on women? I mean, one of the things that you wrote about is that there are a number of women who have been subjected to these tests who have found it extremely traumatic for years afterwards. Could you just talk a little bit about what your reporting indicated around this?

JONES: It was really difficult to get women to open up and talk about this issue because it’s incredibly private. And of the women that I did interview, there was a handful that had undergone this procedure as children, in their teen years around puberty. And all of them said that they found it incredibly traumatizing. And some said that they considered it to be sexual assault or rape.

MARTIN: One of the things that intrigued me is the fact that a doctor would participate in this when you’ve told us that there is no medical purpose to it. I mean, there is no medical purpose to it. So why would a doctor perform this test on a healthy person?

JONES: That’s a really good question, and that’s a question I’ve asked several dozen physicians and nurses and sexual assault nurses. And they say – they have a variety of different answers. Some just don’t want to talk about the fact that they’re performing these exams because it might be due to ignorance. Even in medical school, the hymen is not widely studied, and even among doctors that I interviewed in the States, there was sort of a lack of understanding around the hymen and the role that it plays or does not play in the female anatomy.

MARTIN: So before we let you go, I noted that this story about T.I., who’s, you know, a very well-known figure – and I know a lot of people reacted with kind of horror and disgust when he was discussing this issue in this way – you know, so freely on a public forum. And I just wondered, how did you react to this as a person who’s reported on this?

JONES: So I wasn’t totally surprised. I was just surprised that about a week after I published this year-long investigation about virginity testing, and it was so difficult to find women and medical professionals to come forward and talk about this issue, that this story popped up in my news feed that T.I. was bringing his daughter to get her hymen checked. And it sort of blew up the story in a much bigger way and gave it a platform where people were actually discussing this issue – where before, before this investigation, I had not ever read a story about virginity testing in the U.S.

MARTIN: That was Sophia Jones, senior editor and journalist with the Fuller Project. It’s a project that reports on issues affecting women and girls around the world.

Sophia Jones, thank you so much for talking to us today.

JONES: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

You Can Get A Master’s In Medical Cannabis In Maryland

Maryland now offers the country’s first master’s degree in the study of the science and therapeutics of cannabis. Pictured, an employee places a bud into a bottle for a customer at a weed dispensary in Denver, Colo.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Summer Kriegshauser is one of 150 students in the inaugural class of the University of Maryland, Baltimore’s Master of Science in Medical Cannabis Science and Therapeutics, the first graduate program of its type in the country.

This will be Kriegshauser’s second master’s degree and she hopes it will offer her a chance to change careers.

“I didn’t want to quit my really great job and work at a dispensary making $12 to $14 an hour,” says Kriegshauser, who is 40. “I really wanted a scientific basis for learning the properties of cannabis — all the cannabinoids and how they interact with the body. I wanted to learn about dosing. I wanted to learn about all the ailments and how cannabis is used within a medical treatment plan, and I just wasn’t finding that anywhere,” she adds.

The program stands largely alone: Some universities offer one-off classes on marijuana and two have created undergraduate degrees in medicinal plant chemistry, but none have yet gone as far as Maryland.

Stretched over two years and conducted almost exclusively online, the program launched as an increasing number of jurisdictions across the country legalize pot — primarily for medical uses, but in some places recreational, as well.

As of mid-October, nearly three dozen states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands had legalized medical cannabis, creating an ever-expanding universe of opportunities for people looking to grow, process, recommend and sell the drug to patients. And given how quickly attitudes and laws on cannabis are shifting, those opportunities are expected to keep expanding.

But even as the industry has quickly grown, expertise has remained largely informal. And for people looking to change careers, like Kriegshauser, getting into the legal cannabis field can seem risky, with the likely job options hard to come by.

The University of Maryland credits the overwhelming response to its graduate program to that desire for more information and opportunity. More than 500 hopefuls applied for what was supposed to be a class of 50, prompting the university to increase the size of the inaugural class threefold. And the class is geographically diverse, coming from 32 states and D.C., plus Hong Kong and Australia.

The students take four required core courses — including one on the history of medical weed and culture, and two basic science classes. Students then choose between a number of electives.

Leah Sera, a pharmacist and the program’s director, says officials at the university see a parallel trend. More and more of their graduates were entering a professional world where cannabis is seen as an alternative medicine for any number of ailments, and one that more patients are curious about.

“There have been a number of studies, primarily with health professionals, indicating that there is an educational gap related to medical cannabis — that health professionals want more education because patients are coming to them with questions about cannabis and therapeutic uses,” Sera says.

Pharmacist Staci Gruber teaches at Harvard Medical School and is leading one of the country’s most ambitious research projects on medical marijuana at McLean Hospital in Boston.

She says Maryland’s program is proof that as the drug becomes ever more present among patients, more research on its effects will be needed.

“I know some say, ‘Oh, it’s just a moneymaker for the institution,’ but it’s because people are asking for it,” she says. “People are interested in learning more and knowing more, so [Maryland’s program] underscores the need to have more data.”

That’s the challenge for an academic program on cannabis; the drug remains largely illegal under federal law, which has hampered its study over the years and means very little concrete research exists for students to dig into. But as that changes, Sera says, the program will continue to evolve.

And she expects that students will see immediate opportunities in the rapidly expanding industry once they graduate.

There remains plenty of uncertainty, of course, and as the recreational use of weed is made legal in more places, established medical cannabis programs, and their associated jobs, may dwindle. But Summer Kriegshauser says making the leap into Maryland’s program made sense for her — and she bets it will pay off.