Express Scripts Takes Steps To Cut Insulin’s Price To Patients

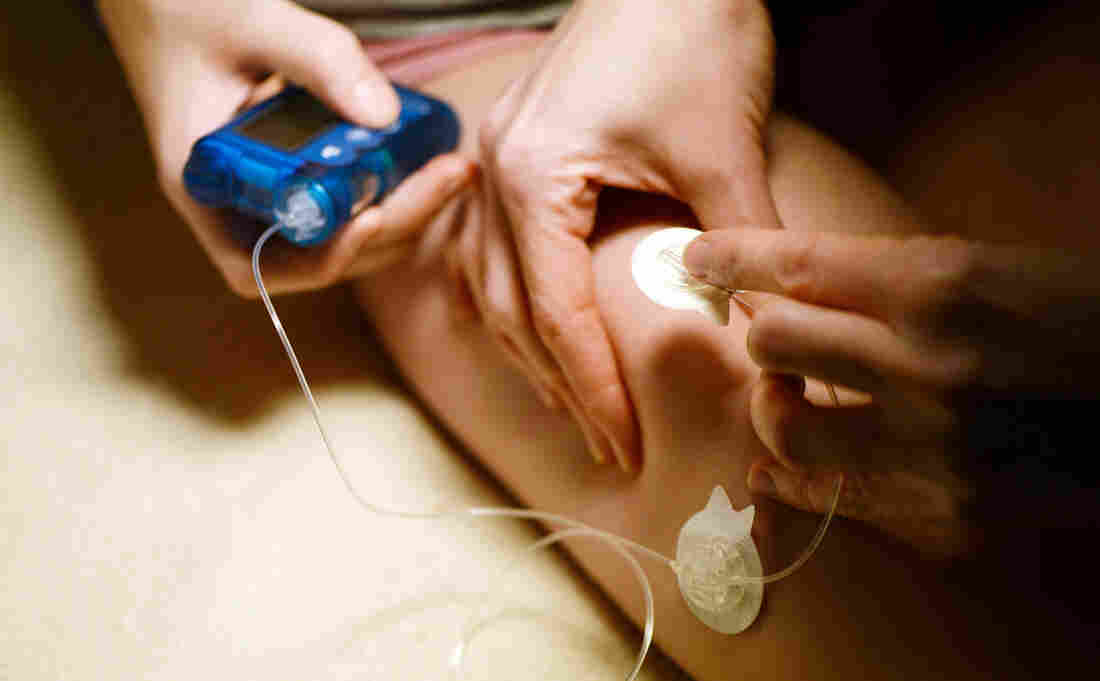

A medical assistant administers insulin to an adolescent patient who has Type 1 diabetes. Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, says it covers 1.4 million people who take insulin.

Picture Alliance/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Picture Alliance/Getty Images

As the heat turns up on drug manufacturers who determine the price of insulin and the health insurers and middlemen who determine what patients pay, one company — Cigna’s Express Scripts — announced Wednesday it will take steps by the end of the year to help limit the drug’s cost to consumers.

Express Scripts, which manages prescription drug insurance for more than 80 million people, is launching a “patient assurance program” that Steve Miller, Cigna’s chief clinical officer, says “caps the copay for a patient at $25 a month for their insulin — no matter what.”

The move by Express Scripts comes as lawmakers are focused on high drug prices and listening to stories about patients who can’t afford their medication.

Insulin has become a major focus. A Minnesota man died last year, according to his mother, when he tried to ration his insulin because he couldn’t afford the $1,300 monthly cost.

Though the drug has been in use for more than a century, its price in the U.S. is 10 times higher than it was 20 years ago, according to a report by the House of Representatives released last week.

“What we’re hoping is that we’re going to see more diabetics taking more insulin, [fewer] complications for those patients, and hopefully lower health care costs,” Miller tells Shots.

Express Scripts covers 1.4 million people who take insulin, Miller says.

Under the discount program, patients who haven’t met their deductible and normally would have to pay the full retail price for their insulin would pay $25. The same goes for those whose normal copayment is a percentage of that retail price. Miller says on average patients pay about $40 a month for insulin copayments — but the price can vary widely month to month, depending on the design of a patient’s prescription drug plan.

The announcement by Express Scripts, one of the biggest pharmacy benefit managers, comes a day after a subcommittee hearing in the House of Representatives that focused on the high costs of insulin.

Patient advocate Gail DeVore testified at the hearing.

“Every day I get emails from people asking, ‘How do I afford insulin?’ ” DeVore told the members of the Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations. “Every day. And every day I have to help them find a way to find insulin.”

DeVore, who has been dependent on insulin to control her diabetes for 47 years, says the full retail price for her insulin is $1,400 per month. She has good insurance, she says, so her cost for that drug is manageable. But her insurance doesn’t cover a second, fast-acting insulin she sometimes needs, so she says she dilutes it to make it last longer.

A recent study by researchers at Yale found that about a quarter of people with diabetes skip doses to save money or use less of the medication than prescribed.

“Patients who rationed insulin were more likely to have poor control of their blood sugars,” Dr. Kasia Lipska, an endocrinologist and assistant professor at Yale, testified at the hearing. She said patients who don’t maintain good control of their blood sugar run the risk of amputations, blindness and other diabetes complications.

Lipska told the lawmakers that drug companies are raising prices for no apparent reason. She urged the committee members to focus on the list prices of the drugs that pharmaceutical companies set rather than worrying about discounts and rebates.

“The bottom line is that drug prices are set by drugmakers,” she told lawmakers. “The list price for insulin has gone up dramatically — and that’s the price that many patients pay. This is what needs to come down. It’s as simple as that.”

Express Scripts’ program doesn’t do that, Miller acknowledges.

“This is not lowering the price of the drug,” Miller says. “We think there is a whole different issue, and that is, ‘What’s the price of pharmaceuticals in the United States?’ This does not address that. This truly is addressing the pain that patients are experiencing at the counter.”

Last month, Eli Lilly & Co. said it would begin selling an “authorized generic” version of one of its insulin products at half the retail price.

According to Express Scripts, its $25 copay deal will be available near the end of this year to patients who are not covered by a government insurance program (such as Medicare or Medicaid).

Congressional Panel: Consumers Shouldn’t Have To Solve Surprise Medical Bill Problem

Surprise bills happen when patients go to a hospital they think is in their insurance network but are seen by doctors or specialists who aren’t.

PeopleImages/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

PeopleImages/Getty Images

One point drew clear agreement Tuesday during a House subcommittee hearing: When it comes to the problem of surprise medical bills, the solution must protect patients — not demand that they be great negotiators.

“It is the providers and insurers, not patients, who should bear the burden of settling on a fair payment,” said Frederick Isasi, the executive director of Families USA. He was one of the witnesses who testified before the House Health, Employment, Labor and Pensions Subcommittee of the Education & Labor Committee.

Surprise, or “balance,” bills happen when patients go to a hospital they think is in their insurance network, but are then seen by a doctor or specialist who isn’t. The patient is then on the hook for an often very high bill — sometimes exceeding thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars.

Stories in the Bill of the Month series by NPR and Kaiser Health News have drawn attention to the problem.

Surprise billing is one of the rare public policy problems that are both bipartisan and in need of a federal solution. Around 60 percent of people are covered by employer-sponsored insurance, which is regulated by the federal government, and aren’t protected by the nearly two dozen state laws governing balance billing.

“We have people on this committee that have done yeoman efforts to come up with solutions in their own states,” said Rep. Tim Walberg, R-Mich., the panel’s ranking member. “I think we have a head start in understanding some of the pitfalls to stay away from and some of the benefits we can go directly toward.”

Several policy solutions have been introduced in Congress and discussed at the White House, but the witnesses testifying before the panel were firm that any answer needed to be worked out between key stakeholders — providers and insurers — instead of forcing consumers to file complaints and go through arbitration processes.

The problem, according to testimony, needs to be solved at the root. Instead of allowing a situation in which patients must negotiate a payment plan after receiving a surprise bill, hospitals and insurers need to remove the incentives for doctors to remain out of network.

Right now, if doctors opt out of an insurance network, they can charge prices that are “largely made up,” said Christen Linke Young, a fellow at USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy.

“We need to limit how much they can be paid in out-of-network scenarios to make it less attractive,” Young said.

Experts offered a few solutions, like capping how much providers can be paid if they are out of network. Ilyse Schuman, senior vice president of health policy at the American Benefits Council, suggested capping reimbursement for out-of-network emergency services at 125 percent of what the physician would get from Medicare.

Rep. Phil Roe, R-Tenn., an obstetrician, expressed concerns that tying payments to Medicare would disadvantage rural communities like his, where Medicare reimburses doctors less.

“We pay our providers less and can keep less than 10 percent of nurses we train in the area because we can’t pay them,” Roe said.

Rep. Susan Wild, a Pennsylvania Democrat, acknowledged that surprise billing is one problem that both parties are motivated to solve, but she was skeptical that a path forward was on the horizon. “The solutions I’m hearing don’t sound workable in the context of our present medical system,” Wild said.

“Isn’t the real problem the fact that we’ve turned over our medical system to private market forces?” she asked.

While price transparency is often touted as the antidote to high medical bills, panelists were adamant that more information alone is not enough to stop balance bills.

Patients usually can’t shop around for an anesthesiologist, for instance, no matter how much information they have.

“Notice isn’t enough here; even if the consumer has perfect information, they can’t do anything with that information,” Young testified. “They can’t go across town to get their anesthesia and go back to the hospital.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service and editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. You can follow Rachel Bluth onTwitter: @RachelHBluth

China To Close Loophole On Fentanyl After U.S. Calls For Opioid Action

Liu Yuejin of China’s National Narcotics Control Commission speaks at a Beijing press conference on Monday. He announced that all fentanyl-related drugs will become controlled substances, effective May 1.

Sam McNeil/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Sam McNeil/AP

China has announced that all variants of fentanyl will be treated as controlled substances, after Washington urged Beijing to stop fueling the opioid epidemic in the United States.

Authorities in China already regulate 25 variants of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid linked to thousands of drug overdose deaths in the U.S. But some manufacturers in China, seeking to evade controls, have introduced slight changes to the molecular structure of their drugs, giving them the legal loophole to manufacture and export before the government can assess the products for safety and medical use.

The decision to regulate all fentanyl-related drugs as controlled substances “puts a wider array of substances under regulation,” Liu Yuejin, an official of China’s National Narcotics Control Commission, said at a press conference in on Monday. The regulation will take effect May 1.

Bryce Pardo, a drug policy researcher at Rand Corporation, tells NPR that in theory, the regulation “future-proofs the law” by including impending chemical modifications.

But China may not be able to enforce the new rules, Pardo says. “[Authorities] already have problems enforcing existing laws.” He says official reports show the country does not have enough inspectors for facilities, and law enforcement would have to “take a sample” from a facility and eventually “analyze whether it’s a fentanyl-related structure.”

Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution who focuses on illegal economies, tells NPR the regulation is “a good step,” but whether China “will have the will and the capacity to do it is a big question.”

The United States and China have been negotiating for better drug control since the Obama era, she adds. In the midst of the trade war with the Trump administration, “China is looking for one area where it can still continue cooperating with the U.S.,” Felbab-Brown says.

The announcement comes after President Xi Jinping vowed in a December meeting with President Trump to classify fentanyl as a controlled substance. After the meeting, Trump called on China to seek the death penalty for fentanyl distributors.

Liu denied on Monday accusations that China is a major contributor to the U.S. opioid crisis, saying Chinese law enforcement has “solved several cases” of illegal fentanyl-related drug manufacturing and distribution. “They are all shipped to the U.S. by criminals through evasive means, through international packages,” Liu said. “The amount is extremely limited and cannot be the main source of the substance in the U.S.”

He said the U.S. opioid problem was mainly caused by “domestic reasons,” according to the South China Morning Post.

According to a 2018 report by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, China remains “the largest source of illicit fentanyl and fentanyl-like substances” in the United States and “illicit manufacturers create new substances faster than they can be controlled.”

Chemical exporters in China secretly send drugs to the West through fake shipment labels and other tactics, the report stated.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that relieves extreme pain. It is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It also is the drug most often found in overdose deaths in the United States. In 2016, fentanyl was linked to more than 18,000 drug overdose deaths, 29 percent of drug overdose deaths that year, according to a National Vital Statistics System report.

Felbab-Brown says China’s new stance on fentanyl-related substances stems partially from a desire to be a global enforcer on drugs. “From a public relations perspective, it’s difficult for China to be accused of being a source of drugs,” she says.

China does not have a monopoly on fentanyl production, she adds. “Even if tomorrow the United States wouldn’t get fentanyl from China, others would step in. Most obviously India, a major source of addictive drugs.”

Jingnan Huo contributed to this report.

Republican Strategist Antonia Ferrier Discusses Trump’s Push For New Health Care Law

NPR’s Audie Cornish speaks with Republican strategist Antonia Ferrier about President Trump’s push for Republicans to come up with a health care law that could replace the Affordable Care Act.

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

It’s deja vu all over again, is most often attributed to baseball great Yogi Berra, but it could just as easily be attributed to anyone following the GOP and health care this week. Earlier, the Trump administration revived its efforts to wipe out the Affordable Care Act, this time by supporting a ruling by a federal judge that the ACA is unconstitutional because of changes to tax law. Now, the move this week caught just about everyone by surprise, but especially congressional Republicans. As he did last time, the president is promising that Republicans will replace the ACA with something better.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: We are going to be, the Republicans, the party of great health care.

CORNISH: Antonia Ferrier is a veteran of congressional Republican leadership. She worked with Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell the last time Republicans tried to repeal and replace the ACA. She joins us now in the studio. Welcome to ALL THINGS CONSIDERED.

ANTONIA FERRIER: Thank you for having me.

CORNISH: So your former boss, Majority Leader McConnell, told reporters that he hopes the president can work something out with Speaker Pelosi. Does that mean he’s sitting this one out?

FERRIER: Well, the reality is that Congress is split in two; the House is controlled by Democrats, the Senate is controlled by Republicans. And if this is something the president wants – it’s his – absolutely his prerogative; he is the president of the United States – then he’s going to have to come to a deal with the speaker. They are the most – two most important people here. And as you did point out, Senate Republicans did try to repeal and replace, and that’s not a deja vu all over again that they would like to experience.

CORNISH: Oh, really? OK.

(LAUGHTER)

CORNISH: So the problem has not been coming up with a plan; the problem is coming up with a plan that anyone can agree on, even within the Republican conference.

FERRIER: Correct.

CORNISH: But has that calculus even changed? I mean, nowadays you have Democrats talking about “Medicare for All.” So it’s a different environment, isn’t it?

FERRIER: It absolutely is. Look, I think the president is right. There needs to be a focus in the Republican Party to figure out what we are for. I think that’s useful.

CORNISH: Why don’t they know? It’s been almost a decade.

FERRIER: (Laughter) Well, that’s a very good question. You know, politics is something – I’m sure your viewers are going to be – listeners, I should say, are going to be shocked to hear that sometimes the easiest political play is to attack policy. And I think, from the Affordable Care Act, when it was passed, it was the largest expansion of government in a generation, and Republicans simply did not support that. The question of what happens once you have a huge new entitlement put into place, pulling it back and replacing it with something else – that’s a whole different ballgame.

So I think it’s very hard at this point to fully repeal and replace this law because states and people have become very used to it. Now, if the president wants to go to a place where he’s coming up with a different sort of idea in terms of coverage, I think that’s worthwhile.

CORNISH: We should point out that this is now heading towards an election year, right?

FERRIER: That’s right.

CORNISH: I mean, what kind of risk does this present for congressional Republicans, that this could be an issue?

FERRIER: Well, I think it’s going to be an issue for both sides because Republicans will attack, as you pointed out…

CORNISH: But Democrats ran and won on it in 2018.

FERRIER: That is absolutely true. But since 2018, the Democrats – and many of them have come out in support of Medicare for All and endorsed the idea of getting rid of private insurance. So I think the waters are pretty muddy. But the reality is, do we really think this is going to happen with Nancy Pelosi being in the House? It seems pretty slim. I think there’s probably more likelihood that I’m going to wake up tomorrow and look like Gisele Bundchen than we’re going to get Nancy Pelosi and Donald Trump to agree on a health care plan.

CORNISH: This has been a failed promise from the Republican Party.

FERRIER: That’s right.

CORNISH: Is this an embarrassment? Is this is a problem, to keep going back to it?

FERRIER: It’s a problem to keep going back for it if they fail, but it’s not a problem if it’s just to present a vision. And if you’re a president running for re-election, as Donald Trump is, maybe this is really about presenting a vision, given the fact that the House is controlled by Democrats.

CORNISH: Antonia Ferrier is a veteran Republican strategist. She’s now a partner at Definers Public Affairs. Thank you for speaking with us.

FERRIER: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

How A Lawsuit Challenging Obamacare Could Affect People With Pre-Existing Conditions

NPR’s Ailsa Chang talks with Sabrina Corlette from Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms about how a lawsuit against Obamacare could impact people with pre-existing conditions.

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

One of the central goals of the Affordable Care Act is to protect people with pre-existing conditions. That means insurers have to cover sick people. The Trump administration announced earlier this week that it supports a federal lawsuit challenging the existence of the ACA. Wiping out the health care law could mean that people with pre-existing conditions won’t be able to get coverage or will have to pay more for insurance.

To talk about all this, we’re joined now by Sabrina Corlette. She’s a professor at the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University. Welcome.

SABRINA CORLETTE: Thank you.

CHANG: So we throw around this phrase a lot – pre-existing conditions – when we’re talking about health care. Can you just first lay out exactly what is a pre-existing condition?

CORLETTE: Well, that can be very much in the eye of the insurance company. In fact, before the Affordable Care Act, many companies maintained lists of up to 400 different conditions that might cause somebody to be denied a policy or to be charged more. And that could range from serious conditions like HIV, AIDS, hemophilia, cancer or could be fairly minor – asthma, glaucoma…

CHANG: Glaucoma.

CORLETTE: (Laughter) Exactly. All of those things could trigger what was called underwriting, where they would screen somebody out or carve out the treatment that you might need to treat that condition and not pay for it.

CHANG: And where did this idea of the pre-existing condition come from in the first place?

CORLETTE: Well, most insurance companies, their business model is based on avoiding risk. They worry that people will wait until they’re sick to sign up for coverage. So to protect themselves from that, they came up with a variety of tools that allow them to screen out people who might cost them money. And that includes denying policies.

It includes charging a higher premium than they would a healthy person. It could mean that they don’t cover certain parts of the benefit package. For example, if you had a history of asthma, they might say, well, we’ll cover you but nothing having to do with an upper respiratory condition.

CHANG: Right. But it sounds like what you’re saying is, this concept of the pre-existing condition, it’s an invention by the insurance industry. This is not some medical term from the medical profession. This is an insurance-invented word or idea.

CORLETTE: That’s absolutely right.

CHANG: So in a way, though, insurers have a point. It is more expensive to cover someone who has an illness.

CORLETTE: Yes, that’s right. And they do worry that, without certain protections in place, people will not buy coverage when they’re healthy and then, you know, when they’re in the ambulance on the way to the hospital, they’ll call up the insurance company and say, please sign me up for a policy. And if that happens, then the system just doesn’t work because premiums will be too expensive and unaffordable for everybody else.

CHANG: OK. But even if the Trump administration is successful in ending the Affordable Care Act in the courts, is it politically possible at this point to completely take away protection for pre-existing conditions because it’s popular among voters in both parties?

CORLETTE: Right. So if the court rules in favor of the Trump administration, these protections will be gone at the federal level. And so Congress would have to step in and restore them. Unfortunately, we have a pretty divided House and Senate, and it’s hard to imagine them coming to agreement. That said, interestingly, the number of states have stepped up to try to enact these protections at the state level.

But there are limits. For example, states are not allowed to pass laws that affect people with employer-based insurance. That’s really a federal responsibility. So states can protect people in the individual market – folks who are buying on their own. But for most of us in employer-based plans, that really would need a federal law change.

CHANG: Sabrina Corlette is a lawyer and professor at Georgetown’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. Thanks so much for coming into the studio today.

CORLETTE: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Federal Judge Again Blocks States' Work Requirements For Medicaid

Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin, a Republican, speaks to state legislators in 2018. Bevin, who is running for re-election this fall, asked the federal government to impose work requirements on many people who receive Medicaid. Bevin’s predecessor, a Democrat, did not seek these requirements when he expanded the program under the Affordable Care Act.

Timothy D. Easley/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Timothy D. Easley/AP

For a second time in nine months, the same federal judge has struck down the Trump administration’s plan to force some Medicaid recipients to work to maintain benefits.

The ruling Wednesday by U.S. District Judge James Boasberg blocks Kentucky from implementing the work requirements and Arkansas from continuing its program. More than 18,000 Arkansas enrollees have lost Medicaid coverage since the state began the mandate last summer.

Boasberg said that the approval of work requirements by the Department of Health and Human Services “is arbitrary and capricious because it did not address … how the project would implicate the ‘core’ objective of Medicaid: the provision of medical coverage to the needy.”

The decision could have repercussions nationally. The Trump administration has approved a total of eight states for work requirements, and seven more states are pending.

Still, health experts say it is likely the decision won’t stop the administration or conservative states from moving forward.

In a statement, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma suggested the rulings would not dissuade her efforts to approve work requirements in other states.

Many health law specialists predict the issue will ultimately be decided by the Supreme Court.

Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin, a Republican, has threatened to scrap the Medicaid expansion unless his state is allowed to proceed with the new rules; if he follows through with that threat, more than 400,000 new enrollees would lose their health coverage. He said the work requirement would help move some adults off the program so the state has enough money to help other enrollees.

Bevin, who is running for re-election this fall, had threatened to end the Medicaid expansion during his last campaign but backed off that pledge after his victory.

Arkansas officials have not said what they plan to do.

In his decision on Kentucky, Boasberg criticized HHS officials for approving the state’s second effort to institute work requirements partly because Bevin threatened to end the Medicaid expansion without it.

Under this reasoning, the judge said, states could threaten to end their expansion or do away with Medicaid “if the Secretary does not approve whatever waiver of whatever Medicaid requirements they wish to obtain. The Secretary could then always approve those waivers, no matter how few people remain on Medicaid thereafter because any waiver would be coverage-promoting, compared to a world in which the state offers no coverage at all.”

The decision by federal officials in 2018 to link work or other activities such as schooling or caregiving to eligibility for benefits is a historic change for Medicaid, which is designed to provide safety-net care for low-income individuals.

Top Trump administration officials have promoted work requirements, saying they incentivize beneficiaries to lead healthier lives. Democrats and advocates for the poor decry the effort as a way to curtail enrollment in the state-federal health insurance entitlement program that covers 72 million Americans.

Despite the full-court press by conservatives, most Medicaid enrollees already work, are seeking work, go to school or care for a loved one, studies show.

Critics of the work policy hailed the latest ruling, which many expected since Boasberg last June stopped Kentucky from moving ahead with an earlier plan for work requirements. The judge then also blasted HHS Secretary Alex Azar for failing to adequately consider the effects of the policy.

“This is a historic decision and a major victory for Medicaid beneficiaries,” said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. “The message to other states considering work requirements is clear — they are not compatible with the objectives of the Medicaid program.”

Sally Pipes, president of the conservative San Francisco-based Pacific Research Institute, called the ruling “a major blow” to the Trump administration but said this won’t end its efforts. “The Department of Health and Human Services is very committed to work requirements under Medicaid,” Pipes said.

“It is my feeling that those who are on Medicaid who are capable of working should be required to work, volunteer or take classes to help them become qualified to work,” she added. “Then there will be more funding available for those who truly need the program and less pressure on state budgets.”

Several states, including Virginia and Kentucky, have used the prospect of work rules to build support among conservatives to support Medicaid expansion, which was one of the key provisions of the Affordable Care Act. That expansion has added more than 15 million adults to the program since 2014.

Previously the program mainly covered children, parents and the disabled.

Particularly irksome to advocates for the poor: Some states, including Alabama, which didn’t expand Medicaid, are seeking work requirements in the traditional Medicaid program for parents who have incomes as low as $4,000 a year.

The legal battle centers on two issues — whether the requirements are permissible under the Medicaid program and whether the administration overstepped its authority in allowing states to test new ways of operating the program.

Alker said that state requests for Medicare waivers in the past have involved experiments that would expand coverage or make the program more efficient. The work requirements mark the first time a waiver explicitly let states reduce the number of people covered by the program.

States such as Kentucky have predicted the new work requirement would lead to tens of thousands of enrollees losing Medicaid benefits, though they argued that some of them would get coverage from new jobs.

Under the work requirements — which vary among the states in terms of which age groups are exempt and how many hours are required — enrollees generally have to prove they have a job, go to school or are volunteers. There are exceptions for people who are ill or taking care of a family member.

In Arkansas, thousands of adults failed to tell the state their work status for three consecutive months, which led to disenrollment. For the first several months last year, Arkansas allowed Medicaid recipients to report their work hours only online. Advocates for the poor said the state’s website was confusing to navigate, particularly for people with limited computer skills.

While the administration said it wanted to test the work requirements, none of the states that have been cleared to begin have a plan to track whether enrollees find jobs or improve their health — the key goals of the program, according to a story in the Los Angeles Times.

Craig Wilson, director of health policy at the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement, a nonpartisan health research group, said he believes policymakers will appeal court rulings all the way to the Supreme Court.

“As long as they hold on to hope that some judge will rule in their favor, states will continue to pursue work requirements,” Wilson said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service and editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Women Tell FDA That More Research Is Needed On Health Risks Of Breast Implants

Advisers to the FDA concluded a meeting Tuesday on the safety of breast implants. What’s emerged is a lack of scientific certainty about the risks implants pose to millions of women who have them.

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

Advisers to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have spent two days focusing on the safety of breast implants. What’s emerged is a lack of scientific certainty about the risks implants pose to the millions of women who have them. NPR’s Patti Neighmond reports.

PATTI NEIGHMOND, BYLINE: The panel heard from manufacturers, plastic surgeons, researchers and women who got implants for reconstruction after mastectomy or for cosmetic reasons. Tara Huppco (ph) told the panel she was a healthy mom and bodybuilder in her mid-30s when she decided to get implants for aesthetic reasons. Problems started just weeks after surgery, when she became extremely exhausted and could no longer remember the names of colleagues at work.

TARA HUPPCO: I had panic attacks that woke me in the night and anxiety that kept me shut in in my house. My hair stopped growing. My vision was blurry. I couldn’t eat without pain and nausea. Every morning, getting out of bed, my legs were numb and my feet burned.

NEIGHMOND: Huppco was one of dozens of women to address the panel about a range of autoimmune-related symptoms, often called Breast Implant Illness. She had her implants removed about a year ago.

HUPPCO: My symptoms are almost all gone. I am the person that I used to be. And if I knew anything of what could have happened, I would have said, no, thank you to my implants.

NEIGHMOND: Like most women who spoke, Huppco implored the FDA to look more closely at safety concerns and move right away to take textured implants off the market. These implants have a bumpy surface to help them stay in place, but there’s an increasing number of anecdotal reports suggesting they cause autoimmune illness. They’ve also been linked to a very rare cancer of the immune system.

Even so, most members of the panel say there’s not enough evidence yet to rush textured implants off the market and that larger, longer-term studies are needed. Reina Doria (ph) with the implant manufacturer Mentor says the company provides patient education brochures to doctors to help patients understand potential risks of implants.

REINA DORIA: There may be a gap between what we are providing and what information is reaching the patients. We believe the best way to ensure patient understanding of risk is for them to have a conversation directly with their surgeon.

NEIGHMOND: The FDA panel is not expected to make specific recommendations about implants at this point. It is expected to call for more research into implant safety. Patti Neighmond, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF NOUVELLE VAGUE’S “MANNER OF SPEAKING”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Are The Risks Of Drugs That Enhance Imaging Tests Overblown?

Contrast agent, a drug that enhances CT scans, is sometimes skipped because of concerns about side effects.

Morsa Images/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Morsa Images/Getty Images

One of the most widely used drugs in the world isn’t really a drug, at least not in the usual sense.

It’s more like a dye.

Physicians call this drug “contrast,” shorthand for contrast agent.

Contrast agents are chemical compounds that doctors use to improve the quality of an imaging test. In the emergency room, where I work, contrast is most commonly given intravenously during a CT scan.

About 80 million CT scans are performed annually in the U.S., and the majority are done with contrast.

Most contrast agents I use contain iodine, which can block X-rays. This effect causes parts of an image to light up, which significantly enhances doctors’ ability to detect things like tumors, certain kinds of infections and blood clots.

One thing about contrast agents that makes them different from typical drugs is that they have no direct therapeutic effect. They don’t make you feel better or treat what’s ailing you. But they might be crucial in helping your doctor make the right diagnosis.

Because these drugs are used in some people who might not turn out to have anything wrong with them, and in others who may be seriously ill, contrast agents need to be quite safe.

And by and large they are. Some patients may develop serious allergic reactions or cardiovascular complications, but these are rare. Others may experience nausea or headache.

But there is one widely feared adverse effect of contrast — kidney damage. As a result, contrast is often withheld from patients deemed by their doctors to be at risk for kidney problems. The downside is that these patients may not receive the diagnostic information that would be most useful for them.

In recent years, though, new research has led some physicians to question whether this effect has been overstated.

Is it time to rethink the risk?

The first report of kidney damage after intravenous contrast, which became known as contrast-induced nephropathy, or CIN, appeared in a Scandinavian medical journal in 1954. An early form of contrast had been given to a patient for a diagnostic test. The patient quickly developed renal failure and died. The authors proposed that the contrast may have been responsible, because they could find no other clear cause during an autopsy.

With other physicians now primed to the possibility, similar reports began appearing. By the 1970s, renal injury had become a “well-known complication” of contrast in patients with risk factors for kidney disease, like diabetes. By 1987, intravenous contrast was proclaimed to be the third-leading cause of hospital-acquired kidney failure.

The belief that contrast agents were risky had a significant effect on how often doctors used them. In a 1999 survey of European radiologists, 100 percent of respondents believed that CIN occurred in at least 10-20 percent of at-risk patients, and nearly 20 percent believed it occurred in over 30 percent of such patients. A 2006 survey found that 94 percent of radiologists considered contrast to be contraindicated beyond a certain threshold of renal function — a threshold that nearly 1 in 10 middle-aged American men could exceed.

But Dr. Jeffrey Newhouse, a professor of radiology at Columbia University, had a hunch that something wasn’t quite right with the conventional wisdom. He has administered contrast thousands of times, and rarely did it seem to him that contrast could be said to have been directly toxic. There were often far too many variables at play.

Newhouse decided to go back to the primary literature. In 2006, he and a colleague reviewed more than 3,000 studies on contrast-induced nephropathy and came to an astounding conclusion — only two had used control groups, and neither of those had found that contrast was dangerous.

“Everyone assumed that any kidney injury after contrast was a result of the contrast,” Newhouse said, “but these studies had no control groups!”

In other words, there was no group of patients who hadn’t received contrast to use for comparison.

Newhouse discovered that nearly every study supporting CIN had fallen prey to this shortcoming. The importance of controls in any experiment is elementary-level science; without them, you can’t say anything about causation.

What came next was brilliant. “Having criticized those that did the experiment without the control, we decided to do the control without the experiment,” Newhouse said. He reviewed 10 years of data from 32,000 hospitalized patients, none of whom received contrast. He found that more than half of the patients had fluctuations in their renal function that would have met criteria for CIN had they received contrast.

This raised the possibility that other causes of kidney injury — and not the contrast — could have explained the association found in earlier studies.

Other researchers stepped up after Newhouse published his findings in 2008. Physicians in Wisconsin conducted the first large study of CIN with a control group in 2009. In more than 11,500 patients, overall rates of kidney injury were similar between people who received contrast and those who hadn’t.

There was one major weakness with the study, though — it was retrospective, meaning it relied on medical records and previously collected data. When a study is performed this way, randomization to different treatments can’t be used to guard against biases that could distort results.

So, for instance, if the physicians treating patients in the Wisconsin study were worried about giving contrast to high-risk patients, they may have steered them into the group receiving CT scans without it. These sicker patients might have been more likely to have kidney injury from other causes, which could mask a true difference between the groups.

The next generation of retrospective studies tried to use a special statistical technique to control for these biases.

The first two appeared in 2013. Researchers in Michigan found that contrast was associated with kidney injury in only the highest-risk patients, while counterparts at the Mayo Clinic, using slightly more sophisticated methods, found no association between contrast and kidney injury.

A third study, from Johns Hopkins, appeared in 2017. It, too, found no relationship between contrast and kidney injury in nearly 18,000 patients. And in 2018, a meta-analysis of more than 100,000 patients also found no association.

What did Newhouse make of these results?

“Nearly harmless and totally harmless — we’re somewhere between those two,” he says. “But how much harm is done in withholding the stuff? We just don’t know.”

Still, Dr. Michael Rudnick, a kidney specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, isn’t so sure it’s time to clear contrast agents completely. He thinks there still could be some danger to the highest-risk patients, as the Michigan researchers found. And he pointed out that even sophisticated statistical analyses can’t control for all possible biases. Only a randomized trial can do that.

Here’s the rub, though. Rudnick says we’re unlikely to get a randomized, controlled trial because there’s still a possibility that contrast could be harmful, and ethics committees are unlikely to approve such a trial.

It’s a conundrum that existing belief about contrast agents could actually limit our ability to conduct the appropriate trials to investigate that belief.

Matthew Davenport, lead author of the 2013 Michigan study, and chair of the American College of Radiology’s Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media, says “the vast majority of things we used to think were CIN probably weren’t.”

But he does agree with Rudnick that there could still be real danger for the highest-risk patients. He echoed the current American College of Radiology recommendations that the decision to use contrast in patients with pre-existing renal disease should remain an individualized clinical decision.

For now, if you are in need of a scan that could require contrast, talk about the risks and benefits of the medicine for you and make the decision together with your doctor.

Clayton Dalton is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Controversial 'Abortion Reversal' Regimen Is Put To The Test

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology says suggestions that a medical abortion can be reversed after more than an hour has passed aren’t supported by scientific evidence.

Roy Scott/Ikon Images/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Roy Scott/Ikon Images/Getty Images

Dr. Mitchell Creinin never expected to be in the position of investigating a treatment he doesn’t think works.

And yet, Creinin will be spending the next year or so using a research grant from the Society of Family Planning to put to the test a treatment he sees as dubious — one that recently has gained traction, mostly via the Internet, among groups that oppose abortion. They call it “abortion pill reversal.”

The technique — a series of oral or injected doses of the hormone progesterone given over the course of several days — arose outside the usual avenues of scientific testing, says Creinin, a medical researcher and professor at the University of California, Davis.

Creinin, an OB-GYN, has spent the bulk of his career in family planning research. He has studied topics ranging from different treatments for miscarriage to how women choose birth control methods.

Performing abortions, he says, has always been a part of his practice and philosophy. “I need to provide these services to help women,” Creinin says.

Proponents of “abortion pill reversal” say it can stop a medication-based abortion in the first trimester, if the progesterone is administered in time.

But Creinin says the progesterone treatments are ineffective at best in halting an abortion that has already begun. And, Creinin says, promotion of the treatment can be potentially harmful by giving pregnant women misleading information that an abortion can be undone.

Though critics of abortion pill reversal say the term is an unproven misnomer, it has been such a compelling phrase that it’s already been written into the laws of a number of states.

Legislators in Arkansas, Idaho, South Dakota and Utah have made it a legal requirement in recent years that doctors who provide medical abortions must tell their patients that “reversal” is an option, although they are not prevented from also telling patients if they think the treatment doesn’t work.

Medical researchers such as Creinin and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are concerned by that trend.

“You create a law based on no science — absolutely zero science,” Creinin says.

Proponents of the technique say they do have evidence. But it’s anecdotal, Creinin says, or comes from studies that lack rigorous controls. It’s time, Creinin says, for a formal study that can be definitive.

“I want to own that,” he says.

Abortion choices

In the first 10 weeks of a pregnancy, women who are seeking abortions generally have two options: a surgical procedure or a medication-based abortion (after that, only surgical abortions are performed).

The medication-based regimen uses a combination of two medicines — mifepristone and misoprostol — which women usually take 24 hours apart.

Mifepristone pills work by blocking progesterone, a hormone that helps maintain a pregnancy. The second medicine, misoprostol, makes the uterus contract, to complete the abortion. Studies suggest that 95 percent to 98 percent of women who take both drugs in the prescribed regimen will end the pregnancy without harm to the woman. Surgical evacuation can complete the abortion, if necessary.

So what happens if a woman takes mifepristone, then changes her mind and wants to continue with the pregnancy?

If the change of heart comes in the first hour after she’s swallowed that initial medicine, her doctor might help her induce vomiting. If she hasn’t yet absorbed the first drug, the process may be stopped before it starts.

The bigger question, and one for which the data are murkier, is: What happens if a woman takes the first medicine but never goes on to take misoprostol, the second drug in the regimen?

According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “as many as half of women who take only mifepristone continue their pregnancies.” (If the pregnancy does continue, mifepristone isn’t known to cause birth defects, ACOG notes.)

In 2012, a San Diego physician named George Delgado said he had hit upon a chemical way of stopping the abortion process with more certainty — a way to give more control to a woman who changed her mind. He called his protocol “abortion pill reversal.”

A family medicine physician, Delgado calls himself “pro-life,” not anti-abortion. He says about a decade ago he got interested in the 24-hour window after a woman takes mifepristone but before she takes misoprostol.

He’d received a call from a local activist who said a woman needed Delgado’s help. She had swallowed the first pill in the abortion regimen but had reconsidered and no longer wanted to end her pregnancy.

“People do change their minds all the time,” Delgado says.

Hoping to help the woman, Delgado gave her progesterone — a medication that has many uses, including as a treatment for irregular vaginal bleeding and as part of hormone replacement therapy during menopause. If progesterone is useful in these other ways, Delgado figured, it might stop the action of the progesterone-blocker mifepristone, and halt an abortion.

Delgado says the pregnancy of that first patient continued uneventfully, which he credits to the progesterone.

He then started giving the progesterone treatment to more patients who came to him. He went on to develop a network of clinicians around the country willing to give progesterone to patients who no longer want to go through with their abortions, although he wouldn’t say how many of those clinicians took part in his research.

These days, Delgado says, most women who come to him for the progesterone treatment are self-referrals. While searching online, many find the website for the Abortion Pill Rescue Network, a nationwide group of clinicians who provide the treatment.

The network is backed by Heartbeat International, an anti-abortion rights group, and, according to spokesperson Andrea Trudden, includes more than 500 clinicians willing to prescribe progesterone to patients who have initiated the medication abortion process.

In support of their claims about abortion pill reversal, Delgado and colleagues have published their research in medical journals.

In 2012, Delgado co-authored a report in the Annals of Pharmacotherapy on the experiences of six pregnant women who received mifepristone and then injections of progesterone. Four of the women, the paper said, were able to carry their pregnancies to term.

In a statement released in August 2017, ACOG said the results of the study, a type known as a case series that didn’t include a comparison group, “is not scientific evidence that progesterone resulted in the continuation of those pregnancies.” ACOG’s statement also said: “Case series with no control group are among the weakest forms of medical evidence.”

In 2018, Delgado and colleagues in his network of health providers published a larger case series, this one involving 754 patients, in the journal Issues in Law and Medicine. The paper concluded that the reversal of mifepristone’s effects with progesterone “is safe and effective.”

The researchers acknowledged that the study didn’t randomly assign women to receive a placebo or mifepristone. A study like that, called a randomized placebo-controlled trial, would provide strong evidence. But Delgado and his colleagues wrote that doing this kind of trial “in women who regret their abortion and want to save the pregnancy would be unethical.”

“There’s no alternative treatment,” he says. “You can’t always wait for the [randomized, controlled trials]. If it’s lifesaving, there’s no alternative.”

State legislatures consider “abortion reversal” bills

One of Delgado’s most outspoken critics, Dr. Daniel Grossman, an OB-GYN at the University of California, San Francisco, says all of the published studies supporting this use of progesterone have been marred by methodological flaws that inflate the “success rate” of the reversal treatment.

Last October, Grossman and Kari White, a sociologist at the University of Alabama, Birmingham who studies family planning issues, wrote an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine criticizing Delgado’s research methodology, saying he used flawed statistics and didn’t set rigorous criteria for the characteristics patients had to fulfill to be included in the study.

“A systematic review we coauthored in 2015 found no evidence that pregnancy continuation was more likely after treatment with progesterone as compared with expectant management among women who had taken mifepristone,” they wrote.

“I think there’s a big bias against abortion pill reversal,” Delgado says in response. “ACOG typifies that bias by coming out with strong statements. … This is a new science, but we have a substantial amount of data, and it’s been proven to be safe.”

The critics haven’t slowed Delgado’s supporters.

Already in 2019, legislators in several states — Kansas, Kentucky, North Dakota and Nebraska — have been considering bills that would require abortion providers to tell their patients about abortion reversal. Back in 2017, Delgado testified in support of similar legislation in Colorado, although the proposal never made it into law.

Grossman says he’s furious that states are forcing abortion providers to give their patients inaccurate information related to abortion care.

What’s more, Grossman says, “these laws take an extra step … and essentially are encouraging patients to be a part of clinical research that isn’t really being appropriately monitored. … This is really an experimental treatment.”

Progesterone hasn’t been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration for reversing a medication abortion. Doctors are permitted to prescribe drugs for uses not approved by the FDA as part of the practice of medicine. It’s known as off-label use.

Until Delgado published his 2018 paper, Delgado told his patients they were receiving a “novel treatment.” He says he believes there is now enough research to support the routine off-label prescription of progesterone for women who don’t want to complete a medication-based abortion.

“Now we have a substantial amount of data. There is no alternative. And it’s been proven to be safe,” Delgado says. “Why not give it a chance?”

Although Creinin disagrees that the evidence supports this use of progesterone, he is sympathetic to the idea that women who seek an abortion may not be certain about the decision at their first appointment. Creinin says he supports policies that allow women as much control as possible over the decision about whether or not to terminate a pregnancy.

“There are people who change their minds,” Creinin says. “That’s a normal part of human nature.”

UCSF’s Grossman agrees.

He encourages abortion providers, when possible, to send the mifepristone and misoprostol home with the patient, if she requests it. That way, she can start the protocol only if and when she’s ready, rather than make the decision in a clinic where she might feel rushed. (FDA rules about mifepristone say the pill can only be dispensed in certain types of clinics — usually clinics that provide abortions. And some states have additional restrictions on how and where the drugs can be prescribed and taken.)

Putting abortion reversal to the test

Creinin’s study, approved by the UC Davis institutional review board in December, has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, which tracks medical research.

The study is slated to involve 40 women who are between 44 and 63 days of pregnancy and are seeking to have a surgical abortion. As a condition of the research, the women would have to be willing to take mifepristone, the initial pill that would normally trigger a medical abortion, and then a placebo or progesterone.

Two weeks later, researchers will see if there’s any difference in the rates of continued pregnancy. If progesterone can prevent the effects of mifepristone, Creinin says, he’ll find that more women in the group that got progesterone are still pregnant, with a pregnancy that’s progressing.

The key ethical point, the researchers say, is that all the women in this study want to have an abortion and will get one by the study’s end. The study isn’t enrolling women who are seeking a “reversal.” They will be told upfront that if the mifepristone doesn’t prompt an abortion, they will be offered a surgical abortion.

Creinin says the study participants will be compensated for their time in the study, but won’t be paid for having an abortion. And patients will still be responsible for the cost of the surgical procedure — either through their insurance or out-of-pocket.

Creinin is skeptical that progesterone will have any effect, since it is thought that mifepristone irreversibly blocks progesterone in the body.

But if it does have a clinically significant effect, he says, “I want to know that.”

Creinin hopes that his work will help medical researchers better understand if this kind of treatment can actually help women who change their minds after taking mifepristone for a medication abortion.

If the results show the progesterone doesn’t work, Creinin hopes that it will discourage state legislators from mandating that doctors tell their patients about an ineffective treatment.

Creinin started enrolling patients in the study in February. He isn’t sure how long the study will take, but says he probably won’t have preliminary results for at least a year.

Dr. Mara Gordon is the NPR Health and Media Fellow from the Department of Family Medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

Fentanyl-Linked Deaths: The U.S. Opioid Epidemic's Third Wave Begins

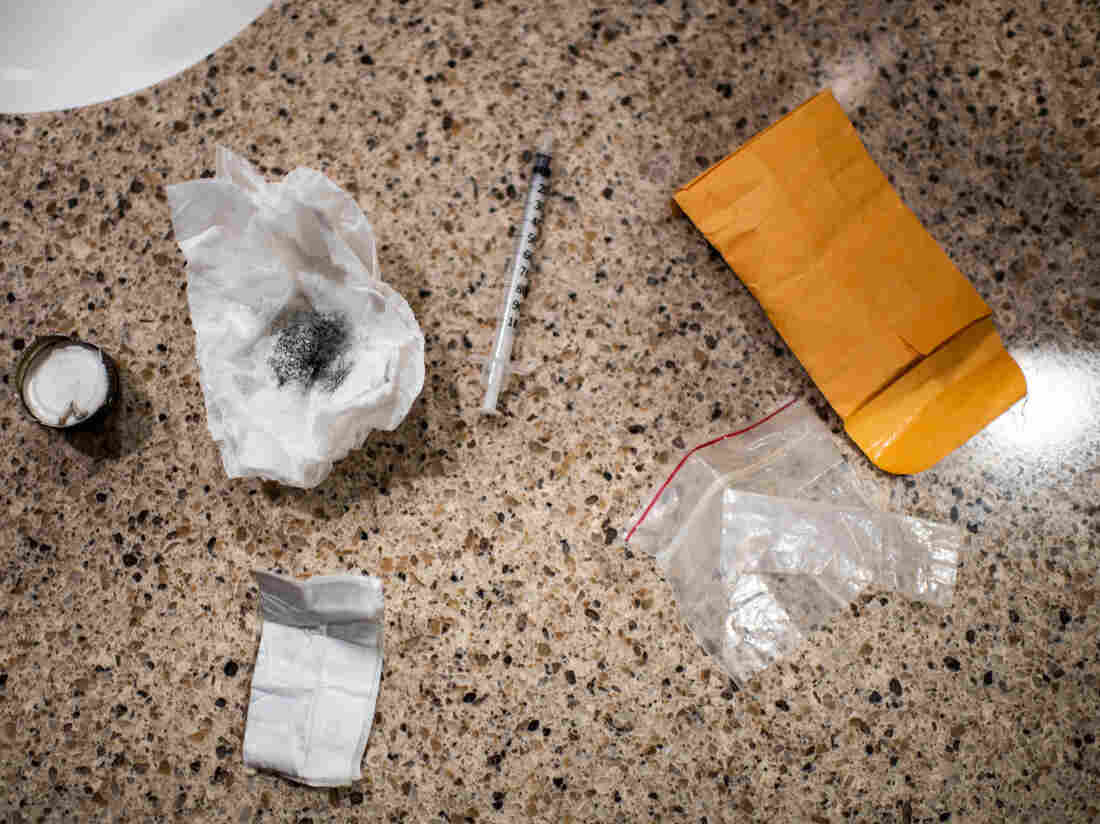

Authorities intercepted a woman using this drug kit in preparation for shooting up a mix of heroin and fentanyl inside a Walmart bathroom last month in Manchester, N.H. Fentanyl offers a particularly potent high but also can shut down breathing in under a minute.

Salwan Georges/Washington Post/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Salwan Georges/Washington Post/Getty Images

Men are dying after opioid overdoses at nearly three times the rate of women in the United States. Overdose deaths are increasing faster among black and Latino Americans than among whites. And there’s an especially steep rise in the number of young adults ages 25 to 34 whose death certificates include some version of the drug fentanyl.

These findings, published Thursday in a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, highlight the start of the third wave of the nation’s opioid epidemic. The first was prescription pain medications, such as OxyContin; then heroin, which replaced pills when they became too expensive; and now fentanyl.

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that can shut down breathing in less than a minute, and its popularity in the U.S. began to surge at the end of 2013. For each of the next three years, fatal overdoses involving fentanyl doubled, “rising at an exponential rate,” says Merianne Rose Spencer, a statistician at the CDC and one of the study’s authors.

Spencer’s research shows a 113 percent average annual increase from 2013 to 2016 (when adjusted for age). That total was first reported late in 2018, but Spencer looked deeper with this report into the demographic characteristics of those people dying from fentanyl overdoses.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

Increased trafficking of the drug and increased use are both fueling the spike in fentanyl deaths. For drug dealers, fentanyl is easier to produce than some other opioids. Unlike the poppies needed for heroin, which can be spoiled by weather or a bad harvest, fentanyl’s ingredients are easily supplied; it’s a synthetic combination of chemicals, often produced in China and packaged in Mexico, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. And because fentanyl can be 50 times more powerful than heroin, smaller amounts translate to bigger profits.

Jon DeLena, assistant special agent in charge of the DEA’s New England Field Division, says one kilogram of fentanyl, driven across the southern U.S. border, can be mixed with fillers or other drugs to create six or eight kilograms for sale.

“I mean, imagine that business model,” DeLena says. “If you went to any small-business owner and said, ‘Hey, I have a way to make your product eight times the product that you have now,’ there’s a tremendous windfall in there.”

For drug users, fentanyl is more likely to cause an overdose than heroin because it is so potent and because the high fades more quickly than with heroin. Drug users say they inject more frequently with fentanyl because the high doesn’t last as long — and more frequent injecting adds to their risk of overdose.

Fentanyl is also showing up in some supplies of cocaine and methamphetamines, which means that some people who don’t even know they need to worry about a fentanyl overdose are dying.

There are several ways fentanyl can wind up in a dose of some other drug. The mixing may be intentional, as a person seeks a more intense or different kind of high. It may happen as an accidental contamination, as dealers package their fentanyl and other drugs in the same place.

Or dealers may be adding fentanyl to cocaine and meth on purpose, in an effort to expand their clientele of users hooked on fentanyl.

“That’s something we have to consider,” says David Kelley, referring to the intentional addition of fentanyl to cocaine, heroin or other drugs by dealers. Kelley is deputy director of the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. “The fact that we’ve had instances where it’s been present with different drugs leads one to believe that could be a possibility.”

The picture gets more complicated, says Kelley, as dealers develop new forms of fentanyl that are even more deadly. The new CDC report shows dozens of varieties of the drug now on the streets.

The highest rates of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths were found in New England, according to the study, followed by states in the Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest. But fentanyl deaths had barely increased in the West — including in Hawaii and Alaska — as of the end of 2016.

Researchers have no firm explanations for these geographic differences, but some people watching the trends have theories. One is that it’s easier to mix a few white fentanyl crystals into the powdered form of heroin that is more common in eastern states than into the black tar heroin that is sold more routinely in the West. Another hypothesis holds that drug cartels used New England as a test market for fentanyl because the region has a strong, long-standing market for opioids.

Spencer, the study’s main author, hopes that some of the other characteristics of the wave of fentanyl highlighted in this report will help shape the public response. Why, for example, did the influx of fentanyl increase the overdose death rate among men to nearly three times the rate of overdose deaths among women?

Some research points to one particular factor: Men are more likely to use drugs alone. In the era of fentanyl, that increases a man’s chances of an overdose and death, says Ricky Bluthenthal, a professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

“You have stigma around your drug use, so you hide it,” Bluthenthal says. “You use by yourself in an unsupervised setting. [If] there’s fentanyl in it, then you die.”

Traci Green, deputy director of Boston Medical Center’s Injury Prevention Center, offers some other reasons. Women are more likely to buy and use drugs with a partner, Green says. And women are more likely to call for help — including 911 — and to seek help, including treatment.

“Women go to the doctor more,” she says. “We have health issues that take us to the doctor more. So we have more opportunities to help.”

Green notes that every interaction with a health care provider is a chance to bring someone into treatment. So this finding should encourage more outreach, she says, and encourage health care providers to find more ways to connect with active drug users.

As to why fentanyl seems to be hitting blacks and Latinos disproportionately as compared with whites, Green mentions the higher incarceration rates for blacks and Latinos. Those who formerly used opioids heavily face a particularly high risk of overdose when they leave jail or prison and inject fentanyl, she notes; they’ve lost their tolerance to high levels of the drugs.

There are also reports that African-Americans and Latinos are less likely to call 911 because they don’t trust first responders, and medication-based treatment may not be as available to racial minorities. Many Latinos say bilingual treatment programs are hard to find.

Spencer says the deaths attributed to fentanyl in her study should be seen as a minimum number — there are likely more that weren’t counted. Coroners in some states don’t test for the drug or don’t have equipment that can detect one of the dozens of new variations of fentanyl that would appear if sophisticated tests were more widely available.

There are signs the fentanyl surge continues. Kelley, with the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, notes that fentanyl seizures are rising. And in Massachusetts, one of the hardest-hit areas, state data show fentanyl present in more than 89 percent of fatal overdoses through October 2018.

Still, in one glimmer of hope, even as the number of overdoses in Massachusetts continues to rise, associated deaths dropped 4 percent last year. Many public health specialists attribute the decrease in deaths to the spreading availability of naloxone, a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with WBUR and Kaiser Health News.