Tylenol For Infants And Children Is The Same. Why Does 1 Cost 3 Times More?

Infants’ Tylenol comes with a dosing syringe, while Children’s Tylenol has a plastic cup. Both contain the same concentration of the active ingredient, acetaminophen.

Ryan Kellman/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Ryan Kellman/NPR

If you’ve ever had a little one at home with a fever, you might have noticed two options for Tylenol at the store.

There’s one for infants and one for children. They contain the same amount of medicine — 160 milligrams of acetaminophen per 5 milliliters of liquid — but the infant version costs three times more.

What gives? It turns out, there’s a backstory.

For decades, Infants’ Tylenol was stronger than the children’s version. The thinking was that you don’t want to give babies lots of liquid medicine to bring down a fever — so you can give them less if it’s stronger.

“It was three times more concentrated,” says Inma Hernandez of the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy. Since it contained more acetaminophen, the active ingredient, she says, it made sense that it was also more expensive. “The price per milliliter was five times higher,” Hernandez says.

But there was a problem: Parents were making mistakes with dosing. Babies got sick — some even died. So in 2011, at the urging of the Food and Drug Administration, the maker of brand-name Tylenol, Johnson & Johnson, announced a change: Infants’ Tylenol would be the same concentration as Children’s Tylenol.

Now it’s the same medicine, but the price is still different.

A quick search online shows 4 ounces of Children’s Tylenol selling for $5.99, and Infants’ Tylenol also selling for $5.99, but for only 1 ounce of medicine. With many store brands of acetaminophen, it’s the same story: The infant version is generally three times more expensive than the one for children.

Kim Montagnino of Johnson & Johnson said in a statement to NPR that Infants’ Tylenol is more expensive because the bottle is more sturdy and it includes a dosing syringe, instead of a plastic cup. “These safety features of Infants’ Tylenol (dosing syringe, rigid bottle) are more expensive to manufacture than the dosing cup and bottle for Children’s Tylenol,” Montagnino wrote.

Hernandez doesn’t buy it.

“The cup versus the syringe doesn’t really explain the price difference in my opinion,” Hernandez says. “They’re really cheap because they’re just plastic. When we think of what’s expensive in a drug, it’s actually the active ingredient, and the preparation of that active ingredient in the formulation, not the plastic cup or the syringe.”

But Johnson & Johnson’s explanation makes sense to Edgar Dworsky, a consumer advocate and founder of the website Consumer World. “There’s an extra thing in the box, and extra things usually cost money,” he says.

“Think of a spray cleaner. You can buy the spray cleaner in the spray bottle, and that costs a little more money. Or you can buy the refill that gives you more ounces but it doesn’t have the sprayer on top — it’s kind of the same concept.”

But this, of course, is not a spray cleaner. It’s medicine. And parents are sensitive to marketing because the stakes are so high.

“I would certainly imagine that product-makers know that parents want to be very cautious when buying products for their kids,” Dworsky says. “Really, the lesson is — read the label. See what you’re getting for your money.”

Pediatrician Ankoor Shah at Children’s National Health System in Washington, D.C., knows how confusing all of this is for parents because he gets tons of questions from them about over-the-counter medications.

“The packaging and the dosing is not easy, it’s not simple and — personal opinion — it’s not parent-friendly,” Shah says.

For instance, Infants’ Tylenol doesn’t say on the label what the correct dosing is for a baby under age 2. It just says “ask a doctor.” Shah says he still uses a calculator to figure out how much to give a child, based on their weight, and gives slips to parents at kids’ well visits. You can also find the information from reputable sources online.

He says whether you opt for the Children’s or Infants’ bottle of acetaminophen at the store, the most important thing is to get the dosing right.

“When you start giving more acetaminophen than recommended, there are serious side effects that could happen,” he says.

The bottom line is: Know what you need. And if you need to spend that extra couple of dollars for the syringe and the special bottle to get the dosing just right, maybe the markup is worth it.

If you think you might have inadvertently overdosed a child, contact your doctor or call your local poison control center. There are 55 poison control centers across the U.S.; all of them can be reached at the same hotline number: 1-800-222-1222.

Colorado Caps Insulin Co-Pays At $100 For Insured Residents

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, pictured in January, signed a bill into law on Wednesday placing a $100 per month cap on insulin co-payments starting next year.

David Zalubowski/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

David Zalubowski/AP

As nearly 7.5 million Americans contend with covering the skyrocketing costs of insulin to manage the disease, diabetics in Colorado will soon have some relief.

A new law, signed by Gov. Jared Polis earlier this week, caps co-payments of the lifesaving medication at $100 a month for insured patients, regardless of the supply they require. Insurance companies will have to absorb the balance.

The law also directs the state’s attorney general to launch an investigation into how prescription insulin prices are set throughout the state and make recommendations to the legislature.

Colorado is the first state to enact such sweeping legislation aiming to shield patients from dramatic insulin price increases.

“One in four type 1 diabetics have reported insulin underuse due to the high cost of insulin … [t]herefore, it is important to enact policies to reduce the costs for Coloradans with diabetes to obtain life-saving and life-sustaining insulin,” the law states.

The price of the drug in the U.S. has increased exponentially in recent years. Between 2002 and 2013, it tripled, according to 2016 study published in the medical journal JAMA. It found the price of a milliliter of insulin rose from $4.34 in 2002 to $12.92 in 2013. And a March report from the House of Representatives, found “prices continued to climb, nearly doubling between 2012 and 2016.”

Dramatic price hikes have left some people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes who use insulin to control their blood sugar levels in the unfortunate position of making dangerous compromises. They either forego the medication or they ration their prescribed dose to stretch it until they can afford the next prescription.

In some instances, those compromises can lead to tragedy. As NPR reported, an uninsured Minnesota man who couldn’t afford to pay for $1,300 worth of diabetes supplies, died of diabetic ketoacidosis, according to his mother. The man, who was 26, had been rationing his insulin.

The move in Colorado comes on the heels of recent commitments by manufacturers to limit the drug’s cost to consumers, which in turn comes on the heels of mounting pressure (and some skewering) from elected officials.

Following a U.S. Senate Finance Committee hearing in February and a subcommittee hearing in the House in April, pharmaceutical company leaders have reluctantly admitted they have a role to play in reducing drug prices.

Last month Express Scripts, one of the largest pharmacy benefit managers in the country, announced it is launching a “patient assurance program” that will place a $25 per month cap on insulin for patients “no matter what.”

In March, insulin manufacturer Eli Lilly said it will soon offer a generic version of Humalog, called Insulin Lispro, at half the cost. That would drop the price of a single vial to $137.35.

“These efforts are not enough,” Inmaculada Hernandez of the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy tells NPR, of the latest legislation in Colorado.

Hernandez was lead author of a January report in Health Affairs attributing the rising cost of prescription drugs to accumulated yearly price hikes.

While the Colorado out-of-pocket caps will likely provide financial relief for diabetes patients, she noted “the costs will kick back to all of the insured population” whose premiums are likely to go up as a result.

“Nothing is free,” Hernandez said.

“It also doesn’t fix the real issue,” she added, pointing to her own research which found “that prices have increased because there’s not enough competition in the market, demand will always be high and manufacturers leverage that to their advantage.”

Abortion Limits Carry Economic Cost For Women

Demonstrators listen to speeches during a rally in support of abortion rights on Thursday in Miami.

Lynne Sladky/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Lynne Sladky/AP

As Republican-led states pass laws restricting abortion in hopes the Supreme Court will overturn its Roe v. Wade decision, supporters of abortion rights are pushing back.

Thousands of women who’ve had abortions have taken to social media to share their experience. Many argue they would have been worse off economically, had they been forced to deliver a baby.

“I didn’t know what I would do with a baby,” said Jeanne Myers, who was unmarried and unemployed when she got pregnant 36 years ago.

“I was horrified,” she said. “I had no job. I would have been in no financial position to care for a kid.”

By the time she knew she was pregnant, Myers was already in her second trimester — too late for an abortion in Janesville, Wisc., where she lived. So she saved up her money for a trip to a specialty clinic in Madison, where a doctor terminated the pregnancy.

“I cried through the whole procedure,” Myers recalled. “I had guilt probably for a year. But you know what? I don’t regret it. Because if I hadn’t had that procedure when I was young, I would not be where I am today.”

Myers is among the thousands of women who’ve been sharing their stories under the hashtag YouKnowMe in recent days, in an effort to reduce the stigma surrounding abortion and preserve the right for other women. They cite a wide variety of reasons for getting an abortion but a common theme is the economic hardship that having a baby would have posed for both mother and child.

Amanda Payne of Durham, N.C., was just 15 when she got pregnant and totally unprepared to raise a kid.

“I probably would have had to drop out of high school,” she said. “My boyfriend, who ended up being my husband, he had low-paying jobs. We didn’t have anything. I don’t think my life would be what it is today if I had continued that pregnancy.”

A study published in the American Journal of Public Health backs that up. Researchers reached out to more than 800 women who sought abortions around the country, including some who were denied because their pregnancies were too far along. The most common reason the women gave for wanting an abortion was they couldn’t afford to support a child. Researchers then kept tabs on the women and their families for the next five years.

“When we actually look at the outcomes for women, we see that they were right to be concerned,” said Diana Greene Foster, the study’s lead author. “Because women who are denied an abortion and carry the pregnancy to term are more likely to be poor for years after, compared to women who receive the abortion.”

Three out of four women who seek an abortion in the U.S. are already low-income. Foster, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, argues that restricting their access just makes poor women poorer. After all, it’s hard to work full-time with a baby or toddler. And government safety-net programs don’t make up for that lost income or the additional cost of an extra person in the family. About 10% of the women denied abortion in the study put their babies up for adoption.

Of course, to people with a strong moral objection to abortion, economic arguments are beside the point. Opponents often liken abortion to slavery. And just as abolitionists didn’t worry about imposing unwanted costs on plantation owners, anti-abortion forces are not deterred by the high price of child rearing. But polls show most Americans don’t hold such absolutist views about abortion. And with conservative state lawmakers challenging Roe v. Wade, economic research may provide important context.

“If the government is going to step into reproductive decision-making, it’s going to have to consider the economic implications of doing that,” Foster said.

She noted that many women seeking abortion already have other children. And many others want to have kids, once they’re in better circumstances.

That was true of Jeanne Myers, who had a baby daughter three years after her abortion. By that time she was married and both she and her husband were working.

“I wanted to give my kids the best I could. And I did,” Myers said. “I didn’t want to raise a child knowing I couldn’t afford to do it.”

Myers now has two grown daughters. And she worries that when it comes to timing child rearing, they may not have the same options she did.

Surprise Medical Bills Are Driving People Into Debt: Will Congress Act To Stop Them?

Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., is co-sponsoring legislation with Sen. Maggie Hassan, D-N.H., to curtail surprise medical bills.

Susan Walsh/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Susan Walsh/AP

Surprise medical bills — those unexpected and often pricey bills patients face when they get care from a doctor or hospital that isn’t in their insurance network — are the health care problem du jour in Washington, with President Trump and congressional lawmakers from both sides of the aisle calling for action.

These policymakers agree on the need to take patients out of the middle of the fight over charges, but crafting a legislative solution will not be easy.

A hearing of the House Ways and Means health subcommittee Tuesday, for example, quickly devolved into finger-pointing as providers’ and insurers’ testimony showed how much they don’t see eye to eye.

“I’m disappointed that all participants that are going to be here from critical sectors of our economy could not come to find a way to work together to protect patients from these huge surprise bills,” Rep. Devin Nunes, R-Calif., the ranking Republican on the subcommittee, in his opening statement.

As Congress weighs addressing the problem, here’s a guide to the bills and what to watch for.

Senate: Cassidy and Hassan

Last week, Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., and Sen. Maggie Hassan, D-N.H., introduced their version of surprise-billing legislation. It would set out specific protections for patients who are at risk of surprise bills in the following scenarios: receiving emergency care from an out-of-network facility or provider; getting elective care from an out-of-network doctor at a facility that is in the patient’s insurance network; or receiving additional, post-emergency health care at an out-of-network facility because the patient cannot travel without medical transport.

The protections would mean that people in these situations could not be billed by their health providers for amounts outside of what their insurance covered. Similar protections would also be put in place for laboratory and imaging services as well as providers who aren’t physicians, such as nurse anesthetists.

Patients would still have to pay their insurance plan’s usual deductibles and copayments, which would count toward their health plan’s out-of-pocket maximum.

Doctors would be automatically paid a predetermined amount based on what other health plans in the area are paying for a similar service. It’s called the “median in-network rate.”

House: “No Surprises Act”

On the House side, the “No Surprises Act” has emerged as the primary bill. Though it has not been formally introduced, drafts include many of the same protections as in the Cassidy-Hassan measure, including curbs on out-of-network bills for emergency care.

Co-authored by Reps. Frank Pallone, D-N.J., and Greg Walden, R-Ore., respectively the chairman and ranking member of the Energy and Commerce Committee, the measure would require health care facilities to provide 24-hour notice to patients seeking elective treatment that they are about to see an out-of-network provider. It would prohibit the facility or provider from billing patients for whatever amount their insurance companies did not cover for that service. And it would set provider payment rates based on the market in that specific area.

One key difference between the House and Senate proposals: The Cassidy-Hassan measure includes a mechanism by which health providers can challenge that basic median pay rate They would have 30 days to initiate an independent dispute resolution between only the health plan and the provider; patients would be exempted.

“The patient needs to be the reason for care, not the excuse for a bill,” Cassidy said at a press conference when the bill was unveiled.

The approach is often referred to as “baseball-style” arbitration because it’s the model used by Major League Baseball for some salary negotiations. Here’s how it works: The plan and the provider each present a final offer to an independent arbitrator for what the procedure should cost. The arbitrator then picks one of those two options.

Senate, coming soon: Alexander and Murray health care bill

The Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee has primary jurisdiction over the way the federal government regulates employer-sponsored plans, and Chairman Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., and Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., the top Democratic member, are preparing legislation.

That legislative package is being billed as a broader measure designed to address health care costs, which would likely include provisions aimed at surprise medical bills.

If Alexander does proceed on the broader path, his legislation could also incorporate elements such as curbs on drug pricing and price transparency, according to some industry lobbyists.

But this triggers concerns that expanding the measure’s focus — which could perhaps draw more opposition — could slow the momentum behind surprise-billing legislation.

“There’s a lot of other things going on that aren’t directly related to surprise bills,” says Molly Smith, the vice president for coverage and state issues at the American Hospital Association. “We’re paying attention to what else is getting glommed on.”

Alexander and Murray are expected to unveil details of their proposal Thursday. And, at a White House event earlier this month, Alexander said he would like to pass it through the committee by July.

That won’t be the end of players joining in the debate.

In addition to the House Education and Labor Committee hearing and possible legislation, Ways and Means health subcommittee Chairman Lloyd Doggett, D-Texas, is focused on this issue, having introduced surprise-billing legislation in the last three congressional sessions.

Issues to watch

Some Capitol Hill insiders, say arbitration provisions such as those proposed in the Cassidy-Hassan measure could become a hurdle to getting surprise-bill legislation over the finish line.

At the Ways and Means hearing, for instance, a representative from the trade group that represents employer plans called the idea a “snipe hunt” used by providers and hospitals to distract Congress from fixing the problem.

But the idea of the government setting payment rates for doctors is also sensitive. Groups such as the American Medical Association have pushed back on this idea.

“Proposals that use in-network rates as a guideline should be avoided,” said Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, an American Medical Association board member, in testimony to the Ways and Means panel. “Setting payments at these discounted rates would further disrupt the increasing market imbalance favoring health insurers.”

Cassidy, though, was optimistic at the press conference announcing his bill’s introduction.

“Greg Walden on the House side … said that he would be OK with arbitration, so obviously this is a process, we’re in negotiations,” he said at a press conference.

In fact, negotiations between the House and Senate versions of the proposed bills could lead to promising outcomes, says Claire McAndrew, the director of campaigns and partnerships at Families USA, a nonprofit group that advocates for accessible and affordable health care: “There could be an interesting potential to merge these two bills and do a really forward-thinking, consumer-friendly piece of legislation.”

What’s missing

Expensive air and ground ambulance bills have caused controversy in the past, but neither the Senate nor the House proposals appear to address them.

Helicopters are sometimes deployed to get patients in dire need to a hospital quickly, or to service patients in remote areas, often at exorbitant costs.

In addition, Smith, from the hospital association, says none of the bills address insurance network adequacy.

“At the end of the day, surprise billing happens because they don’t have access to an in-network provider,” Smith says.

At some point, legislators will also have to hammer out how the federal law will interact with the more than 20 state laws that address surprise billing, says Adam Beck, the vice president of employer health policy and initiatives at America’s Health Insurance Plans, or AHIP, the trade group representing health insurance plans.

Some states have stricter protections for patients, some use a different method to determine how doctors will be paid, and states want to preserve those extra protections when necessary.

“They’re not necessarily sticking points, but there are real questions they’ll have to figure out,” Beck says.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Struggle To Hire And Keep Doctors In Rural Areas Means Patients Go Without Care

For people living in the small town of Arthur, Neb., getting to a doctor can be a challenge. The nearest hospital is located about 40 miles away in Ogallala.

Krik Siegler/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Krik Siegler/NPR

Taylor Walker is wiping down tables after the lunch rush at the Bunkhouse Bar and Grill in remote Arthur, Nebraska, a tiny dot of a town ringed by cattle ranches.

The 25-year-old has her young son in tow, and she is expecting another baby in August.

“I was just having some terrible pain with this pregnancy and I couldn’t get in with my doctor,” she says.

Visiting her obstetrician in North Platte is a four-hour, round-trip endeavor that usually means missing a day of work. She arrived to a recent visit only to learn that another doctor was on call and hers wasn’t available.

“So then we had to make three trips down there just to get into my regular doctor,” Walker says.

This inconvenience is part of life in Arthur County, a 700-square-mile slice of western Nebraska prairie that’s home to only 465 people. According to census figures, it’s the fifth least-populated county in the nation.

It’s always been a chore to get to a doctor out here, and the situation is getting worse by some measures — here, and in many rural places. A new poll by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that one out of every four people living in rural areas said they couldn’t get the health care they needed recently. And about a quarter of those said the reason was that their health care location was too far or difficult to get to.

Rural hospitals are in decline. Over 100 have closed since 2010 and hundreds more are vulnerable. As of December 2018, there were more than 7,000 areas in the U.S. with health professional shortages, nearly 60 percent of which were in rural areas.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

In Arthur County, it’s a common refrain to hear residents talk about riding out illnesses or going without care unless the situation is dire or life-threatening. Folks will also give you an earful about what happens when they do visit a clinic or hospital. Because of high turnover, doctors don’t know them or their family histories and every visit is like starting all over again, they say.

“It’d be nice to have some doctors stay and get to know their patients,” says Theresa Bowlin, the lone staffer working at the Arthur County courthouse.

Arthur’s population has been in a slow decline for decades. No one knows for sure, but it’s likely the town hasn’t had a full time doctor since the 1930s, though there was a mobile health clinic that used to park on the highway once a week up until the 1990s. But it got too expensive.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

Bowlin says it’s a perennial challenge to find a doctor who knows the community and understands the cowboy mentality about health care common here.

“The younger doctors coming in, they really don’t know how a cowboy can go that long with pain and not come to the doctor until he absolutely has to,” she says.

A generational shift

There’s a changing of the guard going on in the health care industry, and its effects may be most apparent in rural America. As baby boomer doctors retire, independent family practices are closing, especially in small towns. Only 1% of doctors in their final year of medical school say they want to live in communities under 10,000; only 2% were wanted to live in towns of 25,000 or fewer.

Taking over a small-town practice is too expensive, or in some cases, too time-consuming for younger, millennial physicians. And a lot of the newly minted doctors out of medical training are opting to work at hospitals, rather than opening their own practices.

The CEO at the Ogallala Community Hospital in Ogallala, Neb., began offering $100,000 signing bonuses to attract doctors to the town.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Theo Stroomer for NPR

The nearest hospital to Arthur is 40 miles south in the town of Ogallala. Christopher Wong, 36, is one of just two family practice obstetricians at Ogallala Community Hospital, which serves a vast area of some 15,000 people spread across several counties.

Wong grew up in suburban Denver, about a three-hour drive away, but world’s apart from western Nebraska

“Most of the people I take care of out here are ranchers and farmers,” Wong says.

Wong first got interested in rural health care during med school, doing volunteer work in rural Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina. Still, working full time in a small town in rural Nebraska has been an adjustment.

One day, he did rounds at the hospital, saw dozens of patients at the clinic and signed a birth certificate for a baby he’d just delivered. He and the mother had to get a little creative, Wong recalled. She had a history of going into labor fast, but lives more than an hour’s drive from the hospital. Plus it’s calving season on her ranch. And she wasn’t sure her husband would be nearby — or available — to drive her to the hospital.

“So we brought her into the hospital when she was 39 weeks so we could induce her,” Wong says.

Christopher Wong (left) and Jessica Leibhart, are family practice physicians at Ogallala Community Hospital in Ogallala, Neb. Wong, who has worked at the hospital for almost three years, says he has no plans to leave. Leibhart grew up about fifty miles away from Ogallala and said she wanted to live in the small town.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Being a doctor in a small town, you’re always on, even when you’re not. It’s not like you can just clock out and leave work. Wong will bump into a patient at the grocery store who politely asks about this ailment or that problem. Everyone knows him and there’s no anonymity. He’s also on call every other weekend.

“It’s very hard to get away,” Wong says. “It’s hard to separate it all.”

He has a girlfriend in Denver and tries to get down there when he can. But it’s a tough sell to convince a partner to move to rural Nebraska where there are few other young professionals or opportunities.

“I think that’s why it’s also hard to get physicians into rural practice because it’s hard to maintain a personal life.”

Burnout is high. Wong is approaching three years on the job in Ogallala and has no plans to leave. But it’s a constant worry for hospital administrators.

“Work-life balance is a big piece, they want to go home at some time,” says Drew Dostal, CEO of Ogallala Community.

Doctors like Wong, who do both family practice and obstetrics are already in high demand. Dostal even offers $100,000 signing bonuses to help ease their debt burden. It may get them out here for a few years, he says, but they’re usually lured away by other offers and rarely become fully part of the community.

“Physicians who have to move on to help get their debt paid off …[that] challenges patients as well,” Dostal says. “They want to know [their doctor], they want them to stay forever, but it just isn’t a reality in today’s health care.”

Social matchmakers

Dostal is currently looking for a third family practice doctor and could probably hire a fourth. Retaining doctors is key to keeping critical access hospitals like this one open. In the NPR poll, close to one out of every ten respondents said their small town hospital had recently closed.

Recruiting and retaining doctors is so pressing that hospital officials even try to become social matchmakers. If a doctor likes sports, for example, administrators may suggest they volunteer as team physician at the high school; or if they are an arts lover, they could volunteer on the planning committee for the local arts festival.

“If we don’t do a better job of doing that, there is a risk for rural places to lose their hospital, or lose their providers that are in that hospital,” says Dr. Jeffrey Bacon, the chief medical officer for three Banner Health hospitals in northeast Colorado and western Nebraska, including in Ogallala.

One out of every four Americans living in rural America said they had problems accessing needed health care recently, according to a new poll by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. In small towns like Ogallala, the challenge for health care providers is attracting doctors who want to live there.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Bacon and other hospital officials say a more effective solution than social matchmaking or signing bonuses might be if medical schools did more active recruiting in small towns.

In January, Ogallala Community was thrilled to hire Jessica Leibhart to join Wong as a second family practice OB-GYN. Leibhart, 36, grew up in Imperial, Neb., about fifty miles south of Ogallala.

“I was looking to get back to my roots,” Leibhart says. “This was really close and looked like the right fit for us.”

Leibhart relocated from the Omaha area and her family already had contacts in Ogallala, so the transition has been smooth. She knows that in a small town it’s virtually impossible to escape your job.

“If we’re at Walmart or my husband and I will be out for dinner and then pretty soon someone stops by, but that’s part of it,” Leibhart says. “And that truly is becoming part of the community and part of the family that the small town is.”

Finding doctors who want to be part of the small town family, may be one solution to addressing the worsening doctor shortage in rural America, and the growing urban-rural divide.

What Abortion Was Like In The U.S. Before Roe V. Wade

NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly talks with Karissa Haugeberg, assistant professor of history at Tulane University, about what it was like to get an abortion before Roe v. Wade.

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

Over the weekend, hundreds of people marched on Alabama’s state capitol in Montgomery, protesting what is now the nation’s most restrictive abortion law.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PROTESTERS: Alabama women matter. Alabama women matter. Alabama women matter. Alabama women matter.

KELLY: Abortion rights groups are calling for a national day of action tomorrow in response to new abortion bans in several Southern and Midwestern states. Supporters of these bills welcome the challenge if it will take them all the way to the Supreme Court.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

TERRI COLLINS: My goal with this bill – and I think all of our goal – is to have Roe versus Wade turned over.

KELLY: That’s Alabama State Representative Terri Collins.

So if the ultimate goal of these abortion bans is to overturn Roe and go back to the way it was before that landmark decision, let’s paint a picture of what it meant to get an abortion back then. Karissa Haugeberg is here to help us do that. She teaches history at Tulane University, and she joins me now. Professor Haugeberg, welcome.

KARISSA HAUGEBERG: Delighted to be with you.

KELLY: Start with the numbers. Before the Roe versus Wade decision 1973, how many American women got abortions?

HAUGEBERG: Scholars will probably never be able to answer that question with precision precisely because the procedure was illegal. But scholars estimate that between 20% and 25% of all pregnancies ended in abortion before Roe v. Wade.

KELLY: Well, that prompts me to the next thing I want to ask you about, which is, how risky was it when a woman did decide that she wanted to get an abortion in those days pre-Roe versus Wade – because I think the picture a lot of people maybe have in their head is of back-alley abortions or of women using coat hangers or drinking rat poison to induce abortions.

HAUGEBERG: Immediately before Roe v. Wade, officially approximately 200 women died per year. Historically, the most commonplace method that women have used when they haven’t been able to obtain legal abortions is self-induction. Those are the horror stories that you hear of women trying to fall down stairs or ingesting poisons or using instruments to try to induce an abortion.

Another method that women commonly used was turning to the unregulated market. And some women were able to find providers who were willing to perform abortions safely but criminally at great risk to their professional careers and at risk of being imprisoned themselves.

KELLY: Stay with the question of providers for a moment. As you know, the new Alabama law would make performing abortions a felony. But you are describing that there were, pre-Roe versus Wade, competent doctors and midwives and others who were performing abortions. How did that work?

HAUGEBERG: So one thing that’s kind of interesting is that throughout the period when abortion was criminalized beginning in the mid-19th century – for the most part, physicians were the people who were providing it as well as midwives. And as long as a physician was offering the service, until about the 1930s, they were less vulnerable to being prosecuted or having a police raid their practice. And so there was a vibrant word-of-mouth network that enabled many women to find safe providers. But again, they were always operating in a gray area.

KELLY: So big picture, what aspects of history might repeat should today’s Supreme Court overturn Roe versus Wade?

HAUGEBERG: So when we look at the provision of abortion in the immediate pre-Roe period, I think it’s actually very instructive. We had a patchwork system where women in certain places, like New York, and in certain areas – for example, cities – had much better ability to be able to get to a licensed provider and to afford a provider than women who lived in rural areas. So even in 1971, a woman who lived in rural Louisiana had very little ability, often, to be able to afford to get to New York.

And I think that’s one thing that I see coming back – is that we’re returning to this period where geography matters tremendously, that women in certain states will have the ability to exercise the right to abortion while it’s quickly disappearing and diminishing for women in rural states and in states that have a higher proportion of African-Americans.

KELLY: Let me flip the question around and ask what might look quite different in 2019 from the way things looked in 1971, 1972?

HAUGEBERG: Well, among the differences are some of the technologies. And there are concerted efforts to try to get abortion pills into states that are passing these criminal prohibitions on abortion.

KELLY: So options to terminate a pregnancy chemically, which may not have been available and certainly weren’t widely available in the early ’70s.

HAUGEBERG: Precisely. But if the recent history on contraception and these states’ reluctance to cover contraception is any guide, it wouldn’t be surprising if next there will be a crackdown even on these other chemical options.

KELLY: Karissa Haugeberg – she is an assistant professor of history at Tulane University. Professor Haugeberg, thanks very much.

HAUGEBERG: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Where’s Masculinity Headed? Men’s Groups And Therapists Are Talking

Leonardo Santamaria for NPR

Sean Jin is 31 and says he’d not washed a dish until he was in his sophomore year of college.

“Literally my mom and my grandma would … tell me to stop doing dishes because I’m a man and I shouldn’t be doing dishes.” It was a long time, he says, before he realized their advice and that sensibility were “not OK.”

Now, as part of the Masculinity Action Project, a group of men in Philadelphia who regularly meet to discuss and promote what they see as a healthier masculinity, Jin has been thinking a lot about what men are “supposed to” do and not do.

He joined the peer-led group, he says, because men face real issues like higher rates of suicide than women and much higher rates of incarceration.

“It’s important to have an understanding of these problems as rooted in an economic crisis and a cultural crisis in which there can be a progressive solution,” Jin says.

In supporting each other emotionally, Jin says, men need alternative solutions to those offered by the misogynist incel — “involuntary celibate” — community or other men’s rights activists who believe men are oppressed.

“Incels or the right wing provide a solution that’s really based on more control of women and more violence toward minorities,” Jin says.

Instead, he says, he and his friends seek the sort of answers “in which liberation for minorities and more freedom for women is actually empowering for men.”

Once a month, the Philadelphia men’s group meets to learn about the history of the feminist movement and share experiences — how they learned what “being a man” means and how some of those ideas can harm other people and even themselves. They talk about how best to support each other.

Once a month, a men’s group in Philadelphia meets to exchange ideas and share their experiences. With the support of the group, Jeremy Gillam (third from right), who coaches an after-school hockey league, teaches his team nonviolent responses to aggression on the ice.

Alan Yu for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alan Yu for NPR

This spring, part of one of the group’s meetings involved standing in a public park and giving a one-minute speech about any topic they chose. One man spoke of being mocked and spit upon for liking ballet as a 9-year-old boy; another spoke of his feelings about getting a divorce; a third man shared with the others what it was like to tell his father “I love you” for the first time at the age of 38.

The idea of such mentoring and support groups isn’t new, though today’s movement is trying to broaden its base. Paul Kivel, an activist and co-founder of a similar group that was active from the 1970s to the 1990s in Oakland, Calif., says men’s groups in those days were mostly white and middle-class.

Today, the global nonprofit ManKind Project says it has close to 10,000 members in 21 nations, is ethnically and socioeconomically diverse and aims to draw men of all ages.

“We strive to be increasingly inclusive and affirming of cultural differences, especially with respect to color, class, sexual orientation, faith, age, ability, ethnicity, and nationality,” the group’s website says.

Toby Fraser, a co-leader of the Philadelphia group that Jin attends, says its members range in age from 20 to 40; it’s a mix of heterosexual, queer and gay men.

Simply having a broad group of people who identify as masculine — whatever their age, race or sexual orientation — can serve as a helpful sounding board, Fraser says.

“Rather than just saying, ‘Hey, we’re a group of dudes bonding over how great it is to be dudes,’ ” Fraser says, “it’s like, ‘Hey, we’re a group of people who have been taught similar things that don’t work for us and we see not working or we hear not working for the people around us. How can we support each other to make it different?’ “

Participants are also expected to take those ideas outside the group and make a difference in their communities.

For example, Jeremy Gillam coaches ice hockey and life skills at an after-school hockey program for children in Philadelphia. He says he and his fellow coaches teach the kids in their program that even though the National Hockey League still allows fighting, they should not respond to violence with violence. He says he tells them, “The referee always sees the last violent act, and that’s what’s going to be penalized.”

That advice surprises some boys, Gillam says.

“One of the first things that we heard,” he says, “is, ‘Dad told me to stick up for myself. Dad’s not going to be happy with me if I just let this happen, so I’m going to push back.’ “

Vashti Bledsoe is the program director at Lutheran Settlement House, the Philadelphia nonprofit that organizes the monthly men’s group. She says men in the group have already started talking about how the #MeToo movement pertains to them — and that’s huge.

“These conversations are happening [in the community], whether they’re happening in a healthy or unhealthy way … but people don’t know how to frame it and name it,” Bledsoe says. “What these guys have done is to be very intentional about teaching people how to name [the way ideas about masculinity affect their own actions] and say, ‘It’s OK. It doesn’t make you less of a man to recognize that.’ “

Meanwhile, the American Psychological Association published guidelines this year suggesting that therapists consider masculine social norms when working with male clients. Some traditional ideas of masculinity, the group says, “can have negative consequences for the health of boys and men.”

The guidelines quickly became controversial. New York magazine writer Andrew Sullivan wrote that they “pathologize half of humanity,” and National Review writer David French wrote that the American Psychological Association “declares war on ‘traditional masculinity.’ “

Christopher Liang, an associate professor of counseling psychology at Lehigh University and a co-author of the APA guidelines, says they actually grew out of decades of research and clinical experience.

For example, he says, many of the male clients he treats were taught to suppress their feelings, growing up — to engage in violence or to drink, rather than talk. And when they do open up, he says, their range of emotions can be limited.

“Instead of saying, ‘I’m really upset’, they may say, ‘I’m feeling really angry,’ because anger is one of those emotions that men have been allowed to express,” Liang says.

He says he and his colleagues were surprised by the controversy around the guidelines, which were intended for use by psychologists. The APA advisory group is now working on a shorter version for the general public that they hope could be useful to teachers and parents.

Criticism of the APA guidelines focused on the potentially harmful aspects of masculinity, but the APA points to other masculine norms — such as valuing courage and leadership — as positive.

Aylin Kaya, a doctoral candidate in counseling psychology at the University of Maryland, recently published research that gets at that wider range of masculine norms and stereotypes in a study of male college students.

Some norms, such as the need to be dominant in a relationship or the inability to express emotion, were associated with lower “psychological well-being,” she found. That’s a measure of whether students accepted themselves, had positive relationships with other people and felt “a sense of agency” in their lives, Kaya explains. But the traditional norm of “a drive to win and to succeed” contributed to higher well-being.

Kaya adds that even those findings should be teased apart. A drive to win or succeed could be good for society and for male or female identity if it emphasizes agency and mastery, but bad if people associate their self-worth with beating other people.

Kaya says one potential application of her research would be for psychologists — and men, in general — to separate helpful ideas of masculinity from harmful ones.

“As clinicians,” she says, “our job is to make the invisible visible … asking clients, ‘Where do you get these ideas of how you’re supposed to act? Where did you learn that?’ To help them kind of unpack — ‘I wasn’t born with this; it wasn’t my natural way of being. I was socialized into this; I learned it. And maybe I can start to unlearn it.’ “

For example, Kaya says, some male clients come to her looking for insight because they’ve been struggling with romantic relationships. It turns out, she says, the issue beneath the struggle is that they feel they cannot show emotion without being ridiculed or demeaned, which makes it hard for them to be intimate with their partners.

Given the findings from her study on perceptions of masculinity, Kaya says, she now might ask them to first think about why they feel like they can’t show emotion — whether that’s useful for them — and then work on ways to help them emotionally connect with people.

Highly Potent Weed Has Swept The Market, Raising Concerns About Health Risks

Studies have shown that the levels of THC, the main psychoactive compound in pot, have risen dramatically in the U.S. from 1995 to 2017.

David McNew/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

David McNew/Getty Images

As more states legalize marijuana, more people in the U.S. are buying and using weed — and the kind of weed they can buy has become much stronger.

That concerns scientists who study marijuana and its effects on the body, as well as emergency room doctors who say they’re starting to see more patients who come into the ER with weed-associated issues.

Some 26 million Americans ages 12 and older reported being current marijuana users in 2017, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. It’s not clear how many users have had serious health issues from strong weed, and there’s a lot that’s still unknown about the potential risks. But scientists are starting to learn more about some of them.

The potency of weed depends on the amount of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the main compound responsible for the drug’s psychoactive effects. One study of pot products seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration found the potency increased from about 4% THC in 1995 to about 12% in 2014. By 2017, another study showed, the potency of illicit drug samples had gone up to 17.1% THC.

“That’s an increase of more than 300% from 1995 to about 2017,” says Staci Gruber, director of the Marijuana Investigations for Neuroscientific Discovery (MIND) program at the Harvard-affiliated McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. “I would say that’s a considerable increase.”

And some products with concentrated forms of cannabis, like hash and hash oil, can have as much as 80% to 90% THC, she adds.

“I think most people are aware of the phenomenon that ‘this is not your grand daddy’s weed,’ Gruber says. “I hear this all the time.”

But people might not be aware of the potential health risks of highly potent weed. “The negative effects of cannabis have primarily been isolated and localized to THC,” says Gruber. “So it stands to reason that higher levels of THC may in fact confer a greater risk for negative outcome.”

“In general, people think, ‘Oh, I don’t have to worry about marijuana. It’s a safe drug,’ ” says Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “The notion that it is completely safe drug is incorrect when you start to address the consequences of this very high content of 9THC.”

Pot’s paradoxical effects

THC can have opposite effects on our bodies at high and low doses, Volkow says. Take anxiety levels, for example.

“When someone takes marijuana at a low [THC] content to relax and to stone out, actually, it decreases your anxiety,” she says. But high concentrations can cause panic attacks, and if someone consumes high-enough levels of THC, “you become full-blown psychotic and paranoid.”

Weed can have a similar paradoxical effect on the vascular system. Volkow says: “If you take low-content THC it will increase your blood flow, but high content [THC] can produce massive vasoconstriction, it decreases the flow through the vessels.”

And at low concentrations, THC can be used to treat nausea in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. But Volkow says that “patients that consume high content THC chronically came to the emergency department with a syndrome where they couldn’t stop vomiting and with intense abdominal pain.”

It’s a condition called cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

“The typical patient uses [inhales] about 10 times per day … and they come in with really difficult to treat nausea and vomiting,” says Andrew Monte, an associate professor of emergency medicine and medical toxicology at the University of Colorado’s school of medicine. “Some people have died from this … syndrome, so that is concerning.”

Scientists don’t know exactly how high levels of THC can trigger the syndrome, but the only known treatment is stopping cannabis use.

While the number of people who’ve had the syndrome is small, Monte says he and his colleagues have documented a rise in the number of cases at emergency rooms in Colorado since marijuana was legalized there five years ago. A study by Monte and his team found that cyclical vomiting cases made up about 18% of inhaled cannabis-related cases at his ER.

They also found that statewide, the overall number of ER cases associated with cannabis use has gone up. And Monte says his ER has “seen an approximately a three-fold increase in emergency department visits just by frequency. It doesn’t mean we’re getting overwhelmed by these visits due to cannabis, it’s just that means that there are more patients overall.”

Most people show up at his emergency department because of “intoxication” from too much pot, either straight or mixed with other drugs, Monte says. The bulk of these cases are due to inhaled cannabis, though edibles are associated with more psychiatric visits.

“We’re seeing an increase in psychosis and hallucinations, as well as anxiety and even depression and suicidality,” Monte says.

He thinks the increased potency of marijuana plays a role in all these cases. “Whenever you have a higher dose of one of these types of drugs, the patient is at a higher risk of having an adverse drug event. If the concentration is so much higher … it’s much easier to overshoot the low-level high that they’re looking for.”

Not everyone is at equal risk, Monte adds. “Many many people use cannabis safely,” he says. “The vast majority don’t end up in our emergency department.”

Different risks for users

Some people are more vulnerable than others to the potential negative effects of high THC cannabis.

Adolescent and young adults who use recreationally are especially susceptible because their brains are still developing and are sensitive to drugs in general, says Gruber of the MIND program. In a recent review of existing studies, she found that marijuana use among adolescents affects cognition — especially memory and executive functions, which determine mental flexibility and ability to change our behavior.

Medical marijuana users can face unexpected and unwelcome effects from potent weed. “It’s very important for people to understand that they may not get the response they anticipated,” Gruber notes.

Studies done on the medical benefits of pot usually involve very low doses of THC, says Monte, who adds that those doses “are far lower than what people are getting in a dispensary right now.”

David Dooks, a 51-year-old based in the Boston area turned to marijuana after an ankle surgery last year. “I thought that medical marijuana might be a good alternative to opioids for pain management,” he says.

Based on the advice at a dispensary, David began using a variety of weed with 56.5% THC and says it only “exacerbated the nerve pain.” After experimenting with a few other strains, he says, what worked for him was one with low (0.9%) THC, which eased his nerve pain.

‘Start low, go slow’

Whether people are using recreationally or medically, patients should educate themselves as much as possible and be cautious while using, Monte says.

Avoiding higher THC products and using infrequently can also help reduce risk, Volkow adds. “Anyone who has had a bad experience, whether it’s psychological or biological, they should stay away from this drug,” she notes.

Ask for as much information as possible before buying. “You have to know what’s in your weed,” Gruber says. “Whether or not it’s conventional flower that you’re smoking or vaping, an edible or tincture, it’s very important to know what’s in it.”

And the old saying “start low, go slow,” is a good rule of thumb, she adds. “You can always add, but you can never take it away. Once it’s in, it’s in.”

Alabama Lawmakers Pass Bill Banning Nearly All Abortions

The Alabama Senate has passed an abortion ban that would be one of the most restrictive in the United States. The bill would make it a crime for doctors to perform abortions at any stage of a pregnancy unless a woman’s life is threatened or in case of lethal fetal anomaly.

Dave Martin/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Dave Martin/AP

Updated Wednesday at 12:03 a.m. ET

The Alabama Senate passed a bill Tuesday evening to ban nearly all abortions. The state House had already overwhelmingly approved the legislation. It’s part of a broader anti-abortion strategy to prompt the U.S. Supreme Court to reconsider the right to abortion.

It would be one of the most restrictive abortion bans in the United States. The bill would make it a crime for doctors to perform abortions at any stage of a pregnancy, unless a woman’s life is threatened or in case of a lethal fetal anomaly.

The vote was 25-6, with one abstention.

Doctors in the state would face felony jail time up to 99 years if convicted. But a woman would not be held criminally liable for having an abortion.

Laura Stiller of Montgomery protests outside the Alabama State House as the Senate debates an abortion ban. Stiller calls the legislation political and an “affront to women’s rights.”

Debbie Elliott/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Debbie Elliott/NPR

There are no exceptions in the bill for cases of rape or incest, and that was a sticking point when the Alabama Senate first tried to debate the measure last Thursday. The Republican-majority chamber adjourned in dramatic fashion when leaders tried to strip a committee amendment that would have added an exception for cases of rape or incest.

Sponsors insist they want to limit exceptions because the bill is designed to push the idea that a fetus is a person with rights, in a direct challenge to the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Roe v. Wade decision that established a woman’s right to abortion.

“Human life has rights, and when someone takes those rights, that’s when we as government have to step in,” said Republican Clyde Chambliss, the Senate sponsor of the abortion ban.

The amendment has divided Republicans. Lt. Gov. Will Ainsworth, who presides over the Senate, posted on Twitter that his position is simple — “Abortion is murder.” But other Senate leaders have insisted that there be exceptions for rape and incest.

‘Abortion is murder,’ those three simple words sum up my position on an issue that many falsely claim is a complex one. #PassHB314 #NoAmendments pic.twitter.com/NjpYW2wu8T

— Will Ainsworth (@willainsworthAL) May 13, 2019

Democrats didn’t have the votes to stop the bill but tried to slow down proceedings during the debate.

Democratic Sen. Vivian Davis Figures questioned why supporters would not want victims of rape or incest to have an exception for a horrific act.

“To take that choice away from that person who had such a traumatic act committed against them, to be left with the residue of that person if you will, to have to bring that child into this world and be reminded of it every single day,” Figures said.

Republican Gov. Kay Ivey has not said whether she will sign it, and said she was waiting for a final version of the bill. She is considered a strong opponent of abortion.

The ACLU of Alabama says it will sue if the bill becomes law. “This bill will not take effect anytime in the near future, and abortion will remain a safe, legal medical procedure at all clinics in Alabama,” the organization tweeted Tuesday night, along with a map showing clinic locations in the state.

PLEASE REMEMBER: This bill will not take effect anytime in the near future, and abortion will remain a safe, legal medical procedure at all clinics in Alabama. #mybodymychoice #HB314 pic.twitter.com/vVohsiR5Md

— ACLU of Alabama (@ACLUAlabama) May 15, 2019

“Abortion is still legal in all 50 states,” the ACLU’s national organization wrote. “It’s true that states have passed laws trying to make abortion a crime, but we will sue in court to make sure none of those laws ever go into effect.”

Chipping away at abortion rights

In recent years, conservative states have passed laws that have chipped away at the right to abortion with stricter regulations, including time limits, waiting periods and medical requirements on doctors and clinics. This year state lawmakers are going even further now that there’s a conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court.

“The strategy here is that we will win,” says Alabama Pro-Life Coalition President Eric Johnston, who helped craft the Alabama abortion ban.

“There are a lot of factors and the main one is two new judges that may give the ability to have Roe reviewed,” Johnston said. “And Justice Ginsburg — no one knows about her health.”

So states are pushing the envelope. Several, including Alabama’s neighbors Georgia and Mississippi, have passed laws that prohibit abortion once a fetal heartbeat can be detected. But the drafters of the Alabama bill think by having no threshold other than if a woman is pregnant, their law might be the one ripe for Supreme Court review.

The National Organization for Women denounced the ban’s passage.

“This unconstitutional measure would send women in the state back to the dark days of policymakers having control over their bodies, health and lives,” the organization said in a statement. “NOW firmly believes that women have the constitutional right to safe, legal, affordable and accessible abortion care and we strongly oppose this bill and the other egregious pieces of legislation that extremist lawmakers are trying to pass in what they claim is an attempt to force the Supreme Court to overturn Roe.”

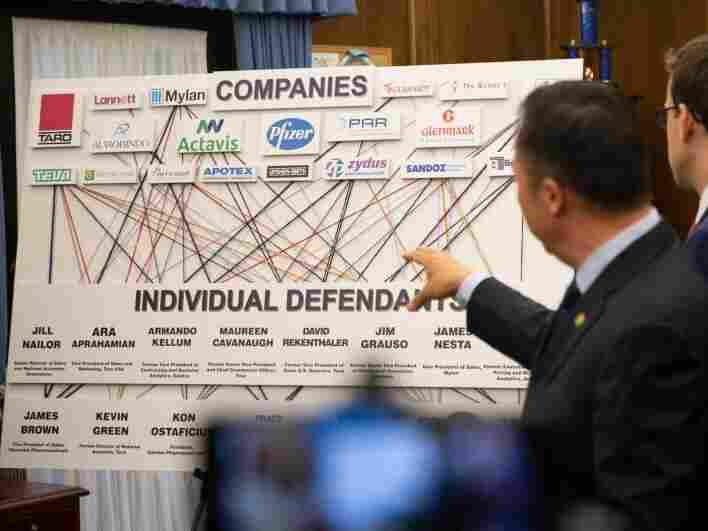

States Sue Drugmakers Over Alleged Generic-Price-Fixing Scheme

Jose A. Bernat Bacete/Getty Images

Connecticut Attorney General William Tong has a skin condition called rosacea, and he says he takes the antibiotic doxycycline once a day for it.

In 2013, the average market price of doxycycline rose from $20 to $1,829 a year later. That’s an increase of over 8,000%.

Tong alleges in a new lawsuit that this kind of price jump is part of an industrywide conspiracy to fix prices.

The suit is a whopper — at least 43 states are suing 20 companies, and the document is over 500 pages long. It was filed Friday in the U.S. District Court in Connecticut.

The lawsuit alleges that sometimes one company would decide to raise prices on a particular drug, and other companies would follow suit. Other times, companies would agree to divide up the market rather than competing for market share by lowering prices.

It says these kind of activities have been happening for years and that companies would avoid creating evidence by making these agreements on golf outings or during “girls nights outs” or over text message.

In several examples, the suit cites call logs between executives at different companies, showing a flurry of phone calls right before several companies would all raise prices in lockstep.

All of this, according to the lawsuit, resulted “in many billions of dollars of harm to the national economy.”

Connecticut Attorney General William Tong says the generic drug industry is profiting “in a highly illegal way” from Americans. Tong is at the forefront of a multistate lawsuit filed May 10 that alleges companies worked together to set prices.

Frankie Grazian/Connecticut Public Radio

hide caption

toggle caption

Frankie Grazian/Connecticut Public Radio

Consumers don’t always notice when a generic drug’s price increases rapidly. People without insurance, of course, pay full price, but even people with insurance can feel the impact.

“More people than ever before are paying based on the price of the drugs,” explains Stacie Dusetzina, a professor at Vanderbilt University who studies drug pricing. Often, patients have to meet a deductible before their health plan’s coverage kicks in, so “they pay full price until they reach a certain level of spending, or they pay a percentage of the drug’s price — we call that a coinsurance.”

Surveys show more Americans are having trouble paying out-of-pocket medical costs. The average annual deductible in job-based health plans has quadrupled in the past 12 years and now averages $1,300.

But, Dusetzina says, even if you only pay a modest copay — such as $5 for every prescription you pick up — if your insurance company is paying more for prescription drugs, it can raise your health plan’s premiums the following year. “So ultimately these costs do get borne by the consumer in some way,” she says.

Dusetzina says what this lawsuit alleges is “very disappointing” — a situation in which consumers put up with the high price of branded drugs because of the implicit promise that a generic is coming some day and will eventually bring the price down.

But that outcome doesn’t happen automatically; it relies on healthy competition and market forces to work. If there’s only one generic version available, that drugmaker can set the price at pretty much the same level as the brand name.

“The higher the number of competitors, the more we see price reductions from the branded drug price,” she says. “So the magic number seems to be around four manufacturers.”

And that assumes those drugmakers aren’t talking to each other and agreeing to coordinate rather than compete.

The main drugmaker cited in the lawsuit is Teva, an Israeli company. In a statement, Kelley Dougherty, vice president of communications and brand, Teva North America, told NPR that the company is reviewing the allegations internally and that Teva “has not engaged in any conduct that would lead to civil or criminal liability.”

The company has also asserted that there’s nothing new here. It’s true that the new lawsuit is similar to past lawsuits, though none of them included so many states as plaintiffs.

Tong has emphasized that the investigation is ongoing. Given the amount of political appetite there is to bring drug prices down, there are certainly more lawsuits to come.