Katherine Streeter for NPR

Sometime around 1907, well before the modern randomized clinical trial was routine, American psychiatrist Henry Cotton began removing decaying teeth from his patients in hopes of curing their mental disorders. If that didn’t work he moved on to more invasive excisions: tonsils, testicles, ovaries and, in some cases, colons.

Cotton was the newly appointed director of the New Jersey State Hospital for the Insane and was acting on a theory proposed by influential Johns Hopkins psychiatrist Adolph Meyer, under whom Cotton had studied, that psychiatric illness is the result of chronic infection. Meyer’s idea was based on observations that patients with high fevers sometimes experience delusions and hallucinations.

Cotton ran with the idea, scalpel in hand.

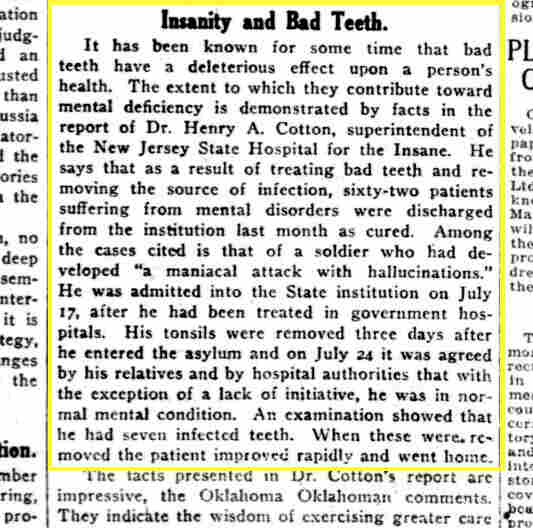

This 1920 newspaper clipping from The Washington Herald highlights Dr. Henry Cotton’s practice of removing infected teeth to treat mental health problems.

In 1921 he published a well-received book on the theory called The Defective Delinquent and Insane: the Relation of Focal Infections to Their Causation, Treatment and Prevention. A few years later The New York Times wrote, “eminent physicians and surgeons testified that the New Jersey State Hospital for the Insane was the most progressive institution in the world for the care of the insane, and that the newer method of treating the insane by the removal of focal infection placed the institution in a unique position with respect to hospitals for the mentally ill.” Eventually Cotton opened a hugely successful private practice, catering to the infected molars of Trenton, N.J., high society.

Following his death in 1933, interest in Cotton’s cures waned. His mortality rates hovered at a troubling 45 percent, and in all likelihood his treatments didn’t work. But though his rogue surgeries were dreadfully misguided and disfiguring, a growing body of research suggests that there might be something to his belief that infection – and with it inflammation – is involved in some forms of mental illness.

Symptoms Of Mental And Physical Illness Can Overlap

Late last year Turhan Canli, an associate professor of psychology and radiology at Stony Brook University, published a paper in the journal Biology of Mood and Anxiety Disorders asserting that depression should be thought of as an infectious disease. “Depressed patients act physically sick,” says Canli. “They’re tired, they lose their appetite, they don’t want to get out of bed.” He notes that while Western medicine practitioners tend to focus on the psychological symptoms of depression, in many non-Western cultures patients who would qualify for a depression diagnosis report primarily physical symptoms, in part because of the stigmatization of mental illness.

“The idea that depression is caused simply by changes in serotonin is not panning out. We need to think about other possible causes and treatments for psychiatric disorders,” says Canli.

His assertion that depression results from infection might seem far-fetched, or at least premature, but there are some data to bolster his claim.

Harkening back to Adolph Meyer’s early 20th century theory, Canli notes how certain infections of the brain – perhaps most notably Toxoplasma gondii — can result in emotional disturbances that mimic psychiatric conditions. He also notes that numerous pathogens have been associated with mental illnesses, including Borna disease virus, Epstein-Barr and certain strains of herpes, including varicella zoster, the virus that causes chickenpox and shingles.

A Danish study published in JAMA Psychiatry in 2013 looked at the medical records of over three million people and found that any history of hospitalization for infection was associated with a 62 percent increased risk of later developing a mood disorder, including depression and bipolar disorder.

Canli believes that pathogens acting directly on the brain may result in psychiatric symptoms; but also that autoimmune activity — or the body’s immune system attacking itself — triggered by infection may also contribute. The Danish study also reported that a past history of an autoimmune disorder increases the risk of a future mood disorder by 45 percent.

Antibodies Provide A Clue

The idea there could be a relationship between the immune system and brain disease isn’t new. Autoantibodies were reported in schizophrenia patients in the 1930s. Subsequent work has detected antibodies to various neurotransmitter receptors in the brains of psychiatric patients, while a number of brain disorders, including multiple sclerosis, are known to involve abnormal immune system activity. Researchers at the University of Virginia recently identified a previously undiscovered network of vessels directly connecting the brain with the immune system; the authors concluded that an interplay between the two could significantly contribute to certain neurologic and psychiatric conditions.

Both infection and autoimmune activity result in inflammation, our body’s response to harmful stimuli, which in part involves a surge in immune system activity. And it’s thought by many in the psychiatric research community that inflammation is somehow involved in depression and perhaps other mental illnesses.

Multiple studies have linked depression with elevated markers of inflammation, including two analyses from 2010 and 2012 that collectively reviewed data from 53 studies, as well as several post-mortem studies. A large body of related research confirms that autoimmune and inflammatory activity in the brain is linked with psychiatric symptoms.

Still, for the most part the research so far finds associations but doesn’t prove cause and effect between inflammation and mental health issues. The apparent links could be a matter of chance or there might be some another factor that hasn’t been identified.

Dr. Roger McIntyre, a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, tells Shots that he believes an upset in the “immune-inflammatory system” is at the core of mental illness and that psychiatric disorders might be an unfortunate cost of our powerful immune defenses. “Throughout evolution our enemy up until vaccines and antibiotics were developed was infection,” he says, “Our immune system evolved to fight infections so we could survive and pass our genes to the next generation. However our immune-inflammatory system doesn’t distinguish between what’s provoking it.” McIntyre explains how stressors of any kind – physical or sexual abuse, sleep deprivation, grief – can activate our immune alarms. “For reasons other than fighting infection our immune-inflammatory response can stay activated for weeks, months or years and result in collateral damage,” he says.

Unlike Canli, McIntyre implicates inflammation in general, not exclusively inflammation caused by infection or direct effects of infection itself, as a major contributor to mental maladies. “It’s unlikely that most people with a mental illness have it as a result of infection,” he says, “But it would be reasonable to hypothesize that a subpopulation of people with depression or bipolar disorder or schizophrenia ended up that way because an infection activated their immune-inflammatory system.” McIntyre says that infection, particularly in the womb, could work in concert with genetics, psychosocial factors and our diet and microbiome to influence immune and inflammatory activity and, in turn, our risk of psychiatric disease.

Trying Drugs Against Inflammation For Mental Illness

The idea that inflammation – whether stirred up by infection or other factors — contributes to or causes mental illness comes with caveats, at least in terms of potential treatments. Trials testing anti-inflammatory drugs have been overall mixed or underwhelming.

A recent meta-analysis reported that supplementing SSRIs like Prozac with regular low-dose aspirin use is associated with a reduced risk of depression and ibuprofen supplementation is linked with lower chances of obtaining psychiatric care. However concomitant treatment with SSRIs and diclofenac or celecoxib – two other anti-inflammatories often used to treat arthritis – was associated with increased risk of needing hospital care due to psychiatric symptoms.

A 2013 study explored the antidepressant potential of Remicade, an drug used in rheumatoid arthritis. Overall, three infusions of the medication were found to be no more effective than a placebo, but patients whose blood had higher levels of an inflammatory marker called C-reactive protein did experience modest benefit.

“The truth of the matter is that there is probably a subset of people who get depressed in response to inflammation,” says lead author Dr. Charles Raison, a psychiatry professor at the University of Arizona. “Maybe their bodies generate more inflammation, or maybe they’re more sensitive to it.”

How infection and other causes of inflammation and overly-aggressive immune activity may contribute to depression and other mental illnesses – and whether or not it’s actually depression driving the inflammation — is still being investigated, and likely will be for some time. But plenty of leading psychiatrists agree that the search for alternative pathologic explanations and treatments for psychiatric disorders is could help jump-start the field.

“I’m not convinced that anti-inflammatory strategies are going to turn out to be the most powerful treatments around,” cautions Raison. “But I think if we really want to understand depression, we definitely have to understand how the immune system talks to the brain. I just don’t think we’ve identified immune-based or anti-inflammatory treatments yet that are going to have big effects in depression.”

But the University of Toronto’s McIntyre has a slightly brighter outlook. “Is depression due to infection, or is it due to something else?” he asks. “The answer is yes and yes. The bottom line is inflammation appears to contribute to depression, and we have interventions to address this.”

McIntyre notes that while the science of psychiatry has a long way to go, and that these interventions haven’t been proved effective, numerous approaches with minimal side effects exist that appear to be generally anti-inflammatory, including exercise, meditation and healthy sleep habits.

He also finds promise in the work of his colleague: “Like most cases in medicine, Charles Raison showed that anti-inflammatory approaches may benefit some people with depression, but not everybody. If you try on your friend’s eyeglasses, chances are they won’t help your vision very much.”

Bret Stetka is a writer based in New York and an editorial director at Medscape. His work has appeared in Wired and Scientific American, and on The Atlantic.com. He graduated from the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 2005. He’s also on Twitter: @BretStetka

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.