Nahnou Houm isn’t Jon Balke’s first Andalusian experiment: 2009’s Siwan also explored traditional music from the region.

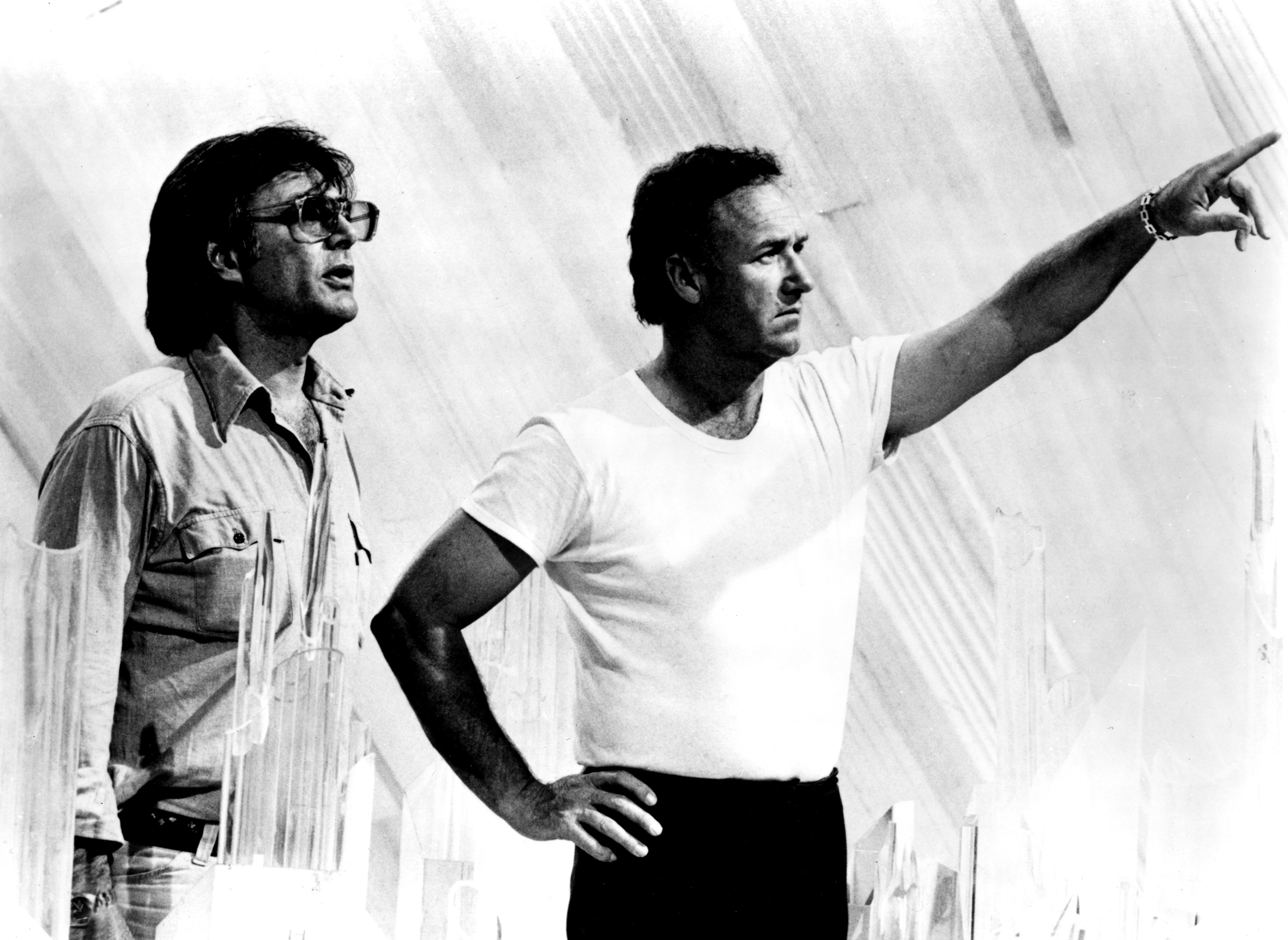

Antonio Baiano for ECM Records/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Antonio Baiano for ECM Records/Courtesy of the artist

Al-Andalus was a region of Spain which, after the expansion of the Islamic Empire, was governed by Muslim rulers for nearly eight centuries – from 711 to 1492.

During the first part of that time, followers of Judaism and Christianity were tolerated by most of the Muslim rulers, which encouraged a relative climate of cooperation between scholars of all three faiths. That climate of cooperation produced advances in math, science, art and music that influenced the rest of Europe.

The region’s spirit has inspired contemporary Norwegian pianist and composer Jon Balke — who, with his group Siwan, recently released his second album drawn from those influences, titled Nahnou Houm.

Balke first learned of Al-Andalus when he was commissioned to write music by a Moroccan promoter to celebrate a venue’s 15th anniversary.

“This was how I stumbled upon Gharnati music, which is the Andalusian music that existed in 1400 in Spain and was driven out,” Balke says.

The intellectual and social exchange fostered by its rulers helped make Al-Andalus one of the most culturally rich areas of Europe. But the Christian kingdoms to the north attacked repeatedly, and in 1492, the Spanish crown reclaimed the last vestiges of the region. Muslims and Jews were either forced to convert, killed or expelled. Many sought refuge across the Mediterranean Sea.

“They left Andalucía and went to North Africa, and Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria,” Mona Boutchebak says.

An Algerian classical singer, Boutchebak is the lead vocalist on the new album by Jon Balke and Siwan. She says the culture of what came to be called Andalusia was carried and preserved by the exiles.

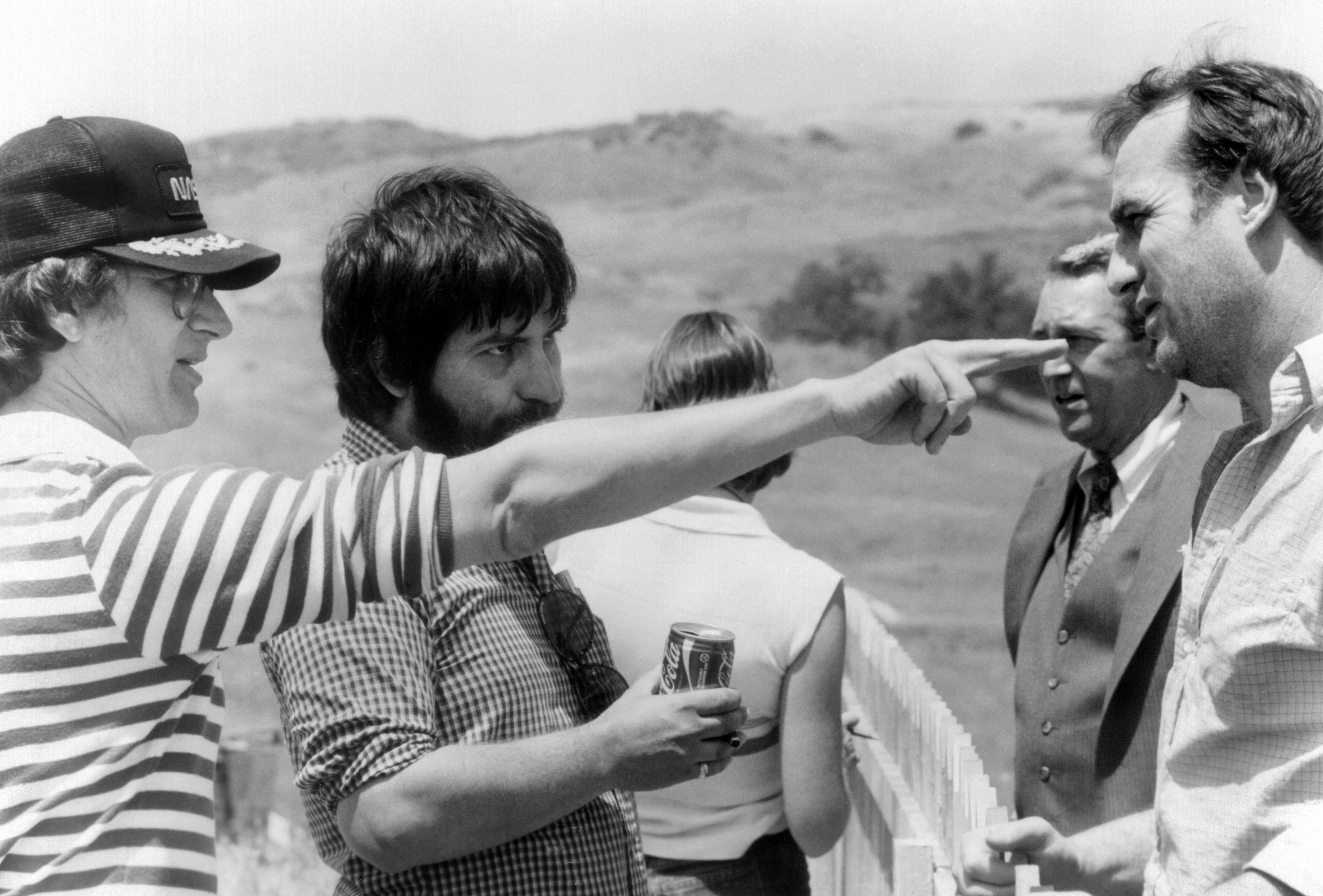

Algerian singer Mona Boutchebak gives the traditional music of Al-Andalus a modern voice.

Antonio Baiano for ECM Records/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Antonio Baiano for ECM Records/Courtesy of the artist

“It is a mixture between Arabic music [and] Spanish,” Boutchebak says. “Flamenco comes from this music, from this tradition. I’m from this tradition, from the Arab-Andalusian one.”

It’s a tradition that’s still taught in schools — “what we call in Algeria the Arabo-Andalusian schools, where you can learn to sing the Arabo-Andalusian tradition,” Boutchebak explains. “So I went and I said, ‘This is what I want to do.’ I started to sing when I was 11, to learn this tradition.”

Jon Balke has taken this tradition’s poetry and composed his own music around it.

“It’s a framing of the musical project,” Balke says. “It puts the project in a framework that speaks about history and that speaks about a kind of a mentality that, from what you can read, existed in the best parts of this period — a kind of open, liberal practice of tolerance and coexistence.

“These poems, they speak about this kind of attitude, even if they speak about love or rain on the river or mystical experiences. You get the kind of a feeling of a period which was a really booming period in European history.”

[embedded content]

YouTube

At first, Boutchebak resisted the idea of combining her ancient tradition with jazz improvisation and music from the north.

“At the beginning, even for me, it was a little bit hard to imagine baroque music, improvisations, Andalusian music, and me in the middle,” she says. “I was asking myself, ‘What am I going to do?’ At times I felt it like it was so far from me, but it isn’t. We are all the same. The title of the album is ‘We Are Them,’ Nahnou Houm.”

Balke hopes that by trying to recapture a long-gone period of cultural and religious coexistence, his Siwan project can offer an alternative intolerance in the modern world.

“It is possible to coexist,” Balke says. “It is possible to respect even a person who believes something different from you or comes from a totally different background. And even if there are conflicts, it’s possible to solve them in another way than shooting the person.”

Let’s block ads! (Why?)