The Thistle & Shamrock: Chansons

Christ Norman plays the flute.

Boxwood, Ltd

hide caption

toggle caption

Boxwood, Ltd

From the “chant de marin,” or sea shanties, of Brittany to the songs of the voyageurs of the Canadian fur trade, enjoy the French songs that extend branches of the Celtic music tree from the old world to the new, with artists Le Vent du Nord, Hilary James and Chris Norman.

Mali’s ‘Guitar Gods’ Tinariwen Receive Racist Threats Ahead Of U.S. Tour

Ahead of a September tour date in Winston-Salem, N.C., social media commenters are leveling violent, racist attacks against the Tuareg musicians known as Tinariwen.

Marie Planeille/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Marie Planeille/Courtesy of the artist

A guitar band from Mali called Tinariwen is famous worldwide. The group’s fans and collaborators have included Robert Plant, Thom Yorke of Radiohead, Bono of U2 and Nels Cline of Wilco. The band has fought extremism in their home country of Mali, and been victims themselves. But ahead of a September show in Winston-Salem, N.C., social media commenters are leveling violent, racist attacks against the musicians.

A refresher on Tinariwen: This a group of Tuareg musicians from the north of Mali. The members have been hailed as guitar gods, playing rolling melodic lines and loping rhythms that evoke the desert sands of the Sahara — the band’s native home. The band’s name literally means “deserts” in their language, Tamasheq.

The first time I saw them play was in Mali, back when it was a safer country than it is today — it was a life-transforming experience. In January 2003, I was lucky enough to travel to see them play at the Festival in the Desert, at a Saharan oasis called Essakane — that’s about 40 miles outside of Timbuktu, to give you a sense of its remoteness. To get there, we drove, off-road, in ramshackle Toyota Land Cruisers over constantly shifting sands.

The stage for the three-day event was set up amidst the desert dunes; we slept in simple tents as Tuareg nomads pitched their tents and camels nearby. (The festival, which was founded in 2001, was built upon a traditional Tuareg festival — a time for nomadic Tuareg to get together, make community decisions, race camels, make music, recite poetry and dance.) There were a few dozen foreigners — Brits, Europeans and Americans, like myself — among hundreds of Tuaregs and their camels.

Camera Production

YouTube

The hope for a larger Festival in the Desert was that it could serve as an economic engine and encourage cultural tourism to northern Mali, a region that has often struggled, and to show cultural unity among Mali’s richly diverse peoples, in the years after the country suffered terrible and bloody conflict in the 1990s. To that end, the organizers invited some incredible Malian musicians who weren’t Tuareg to perform — artists like Ali Farka Touré and Oumou Sangare — along with Robert Plant. The 2003 Festival in the Desert became legendary — and it spurred Tinariwen to worldwide success.

Tinariwen

YouTube

But the Festival in the Desert didn’t last. The political situation in Mali grew more precarious, and by 2012, Islamist extremists — many of them foreigners — fanned out across northern Mali, in hopes of gaining control. Musicians became a prime target. The Festival in the Desert went into exile, and transformed by necessity into an international touring collective.

One of Tinariwen’s own members, the vocalist Intidao (born Abdallah Ag Lamida), was kidnapped by one of those extremist groups, Ansar Dine, in early 2013. Fortunately, he was released. But like many musicians from Mali, Tinariwen has rebuked fundamentalism, and they persevered largely by recording and touring extensively abroad.

Fast-forward to this week. The band is touring the U.S. in September and October to support a new album. A club in Winston-Salem, called The Ramkat booked a show with them for Sept. 17. The venue’s owners put up an ad on Facebook for the show and in response, they started getting a number of racist, vitriolic comments and even violent threats against Tinariwen. (The situation was amplified by the local alternative newspaper, the Triad City Beat, which posted a report on July 19.)

Andy Neville, one of The Ramkat’s owners, told NPR on Tuesday that he found the comments “highly disturbing, hateful, and sad — very sad.”

He continued: “If any of these commenters had done any sort of homework on the band, the Tuareg people or their history, they’d find that the band and the Tuareg people have been marginalized their entire lives — and that Tinariwen themselves have stood up to some of these kind of hateful and and racist forces in North[western] Africa. It’s incredibly disappointing, and then probably the most disappointing thing of all is the fact that we’re talking about these misguided commenters, and what we’re not talking about is what an incredible band Tinariwen is.”

Neville says that he and the other owners have been heartened by positive comments and ticket purchases, however, in the aftermath of the waves of racist and xenophobic comments. Even so, they’re planning to increase security measures on the night of Tinariwen’s show.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice Offers A Sonic Refuge

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his Party, performing live at the WOMAD festival in 1985.

Andrew Catlin/Courtesy of Real World Records

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Catlin/Courtesy of Real World Records

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was hailed as one of the singers of the 20th century. Even now, more than 20 years after his death in 1997, there’s no dearth of opportunities to hear his work, through a combination of sheer popularity, an enormous official discography, and literally thousands of pirated versions. All in all, no one has been suffering for lack for recordings of this Pakistani vocal master of qawwali, a staggeringly beautiful and ecstatic musical form.

Live at WOMAD 1985 comes out July 26 (pre-order).

Stream Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s ‘Live At WOMAD 1985’

01Allah Ho Allah Ho

21:00

02Haq Ali Ali

25:05

03Shahbaaz Qalandar

9:03

04Biba Sada Dil Mor De

9:51

And yet, here we are, with a brand-new issue of Khan captured at his vocal prime, recorded when he was just at the precipice of becoming an international phenomenon: a midnight set recorded in 1985 at England’s WOMAD festival, which was co-founded by Peter Gabriel five years earlier to showcase international music and dance talent. It was the performance that was hailed as Khan’s first real introduction to non-South Asian audiences.

It’s a recording that has languished in the archives for 34 years. (There are some low-quality videos of this performance online, but the sound on this album release, carefully digitized and remixed, is excellent.) Whether for longtime fans or new initiates, Live at WOMAD 1985 is an album to be treasured.

A bit of background for newcomers: qawwali — whose root means “utterance” in Arabic — is a uniquely South Asian musical style. These devotional songs are, in places including Pakistan and India, a core part of Sufism — that is, the mystical branch of Islam that emphasizes a personal connection to God, and embraces the qualities of tolerance, peace, and equality as core principles. (Sufi shrines and gatherings have been targeted for violence by Muslim extremists, both in South Asia and elsewhere.) As Sufism spread from Persia and what is now Turkey to northern India some 800 years ago, its poetry and music were blended with local styles.

Considering the electrifying energy that surges through a qawwali performance, the traditional set-up is rather humble. A group of performers, referred to in English as a “party” – and all male – sit cross-legged on a rug-covered stage. The main singer is usually accompanied by one or two harmoniums to provide melodic support as well as percussion (normally, the tabla and dholak drums), while a small chorus sings and provides heartbeat-like claps.

This 1985 concert marks Khan at his most traditional. It starts out with one of Khan’s signature songs: “Allah Ho” [God Is], which is also known on other recordings as “Allah Hu” or “Allah Hoo.” It’s a hamd, or praise song, and the traditional way of opening a qawwali performance. The audience was slowly drawn in, first through the plush harmonium, beautifully played by Khan’s brother, Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan, and the constant murmur of tabla and the hand claps of the group’s chorus. Those listeners couldn’t have been prepared for what was about to erupt.

Khan — who is often reverently called by the honorific Khan Sahib — was literally born into this style: his family had been qawwals for over 600 years. He learned the family business from his father and uncles — though his father, who was primarily a Hindustani (North Indian) classical singer, dreamed that his son would become a doctor.

His first public performance came at his father’s funeral, when he was just 16 years old. There was a strong adherence to classical music in his family tradition, which you can hear in Khan’s own performances. Without question, he was on fire when he sang — lovers of soul and gospel will find much common ground here. But he was also an exemplary improviser in the Hindustani classical style, using solfege-like swara syllables to race up and down the span of his range, darting between intervals large and small, and always with an ear to the technical and emotional demands of a particular raga.

At WOMAD in 1985, Khan led his neophyte listeners through a very typical qawwali performance arc: after praising God in “Allah Ho,” the group moved to “Haq Ali,” [Ali is Truth], a song devoted to the Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law (and a figure revered by Sufis of both the Sunni and Shi’a sects); “Shabaaz Qalandar,” which honors a 13th century, Afghanistan-born Sufi master; and a more contemporary love song, “Biba Sada Dil Mor De,” which opens with the line “If you can’t remain in front of my eyes, please give me back my heart.” (This style of song, called a ghazal, can be understood as a secular love song or, more mystically, as a devotee’s love of the divine.)

In all, it was a very truncated performance — in more traditional settings, qawwali concerts can go all night — but it was enough to hook listeners in.

In a qawwali performance, the main singer is usually accompanied by one or two harmoniums to provide melodic support as well as percussion, while a small chorus sings and provides heartbeat-like claps.

Jak Kilby/Courtesy of Real World Records

hide caption

toggle caption

Jak Kilby/Courtesy of Real World Records

It’s hard to overstate what a milestone this festival was for Khan. Not long after he gave this performance at WOMAD, the Pakistani artist went on to release a string of studio albums for Peter Gabriel’s tastemaking record label, Real World. (Months after his WOMAD date, he made an excellent series of live recordings in Paris for the French label Ocora, as the late anthropologist and ethnomusicologist Adam Nayyar, a friend of Khan, detailed in a lovely remembrance that he wrote after the singer’s death; around the same time, Khan also made a string of sublime live albums in London, released by the Navras label.)

Live at WOMAD 1985 offers something else, too. It’s a 30-plus-year-old album, which means that — at least for the album’s duration – it offers a sonic refuge from the world we all presently inhabit, one that’s shadowed by decades of fear, suspicion, growing nationalism and acrimony. Not only was it made many years before the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 — right after which some Pakistani immigrants to the U.S. were either deported by the government, or left the country ostensibly of their own accord — but also decades before Pakistanis in the U.S. worried about ICE raids, and a generation before racist rhetoric and heated anti-Muslim comments were part of the daily political salvos fired in the United States. Given what’s elapsed in the past three decades, it’s hard to envision a traditional, firmly Muslim artist reaching the same apex of visibility, or even popularity, in places like the U.S. or the U.K. had he emerged not in 1985, but in 2015.

In retrospect, it’s astonishing to think how beloved Khan became in such short measure. His presence in front of non-South Asian audiences lasted barely a dozen years — yet he counted among his fans Jeff Buckley, Madonna, Mick Jagger, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Eddie Vedder, with whom he recorded. Even so, pressure points around faith, identity and allegiances grew for Khan during his lifetime, and at home. He lamented the state of music, and by extension, the encroaching iron hand of a puritanical form of Islam, in his home country — a sort of fundamentalism that, if it had existed centuries earlier in South Asia, would have precluded qawwali from ever having developed in the first place.

“In Pakistan, people have an indifferent attitude towards music. There are no institutions to teach music and singing,” he told Pakistan’s Herald magazine in 1991. “[Our] people are morally confused about music. Those who want to learn or have learned are always confused and feel guilt. But to tell you the truth, classical music … is not against Islam. It is not haram [forbidden by Islamic principles].”

While his faith was rock-solid, Khan was catholic in his musical tastes; along with eventually making an array of crossover projects with European, British and North American artists, he wrote the music for and appeared in several Bollywood films, on screen or as a playback singer — the rawness smoothed out into honeyed drips of sound.

But Live at WOMAD 1985 offers pure soul — each run up and down the scale a jolt of adrenaline, each beat of the tabla drum and each handclap making the heart pound faster and louder. And this, truly, is the highest purpose of Sufi music: to bring performers and listeners alike into a state of ecstatic union with the divine. In 1993, after a concert that drew 14,000 people to New York’s Central Park, he told Time magazine: “My music is a bridge between people and God.”

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan struggled with his health for a long time, but when the end came, it came quickly. In August 1997, at just 48, he traveled from Pakistan to London for medical treatment; he was rushed straight from the airport to a hospital, where he died of a heart attack. In the 21 years since his death, a raft of younger male relatives have tried to carry Khan’s mantle, as performers of either buoyant qawwali, gauzy love songs, or treacly film tunes. But none of them have sparked the devotion of an international audience the way that Nusrat did. The Shahen-Shah, king of kings, qawwali’s brightest shining star, retains his crown.

The Thistle & Shamrock: Songs Of Tannahill

Emily Smith.

Archie MacFarlane/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Archie MacFarlane/Courtesy of the artist

Hear the music and learn about the short life of 18th century poet Robert Tannahill, who wrote in the style of Robert Burns and composed well-loved songs that are still widely sung today. We feature artists Emily Smith, The Tannahill Weavers and Rod Patterson.

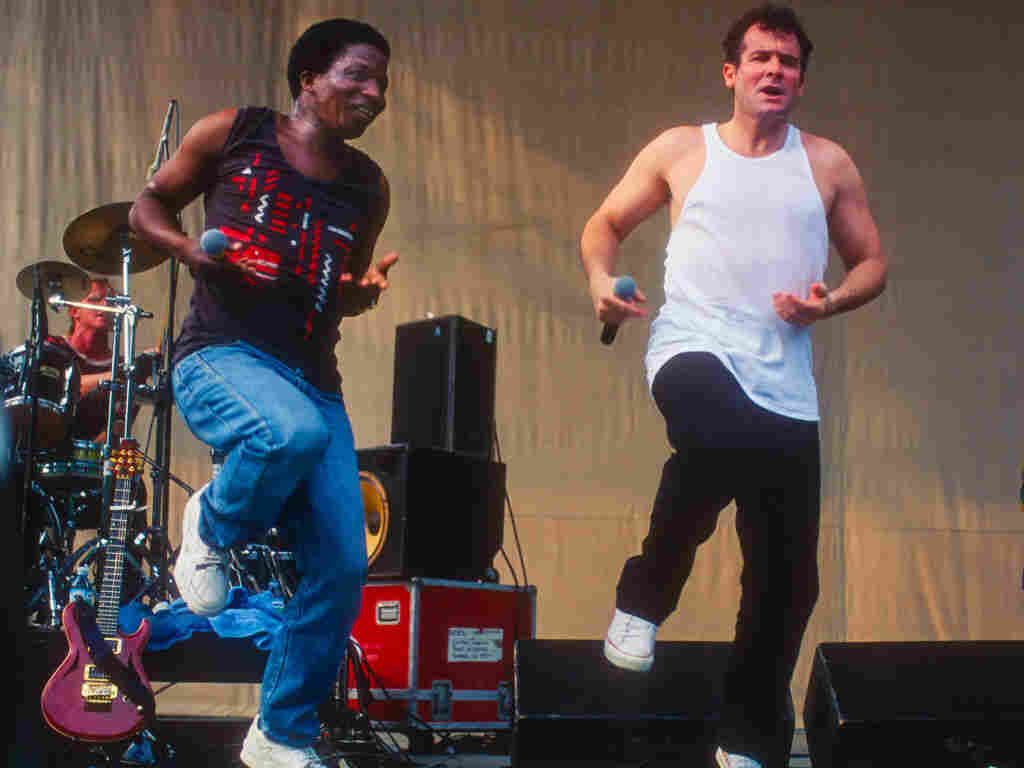

Johnny Clegg, A Uniting Voice Against Apartheid, Dies At 66

South African musician Johnny Clegg, right, with his longtime bandmate Sipho Mchunu, performing in New York City in 1996. Clegg died Tuesday at age 66.

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

One of the most celebrated voices in modern South African music has died. Singer, dancer and activist Johnny Clegg, who co-founded two groundbreaking, racially mixed bands during the apartheid era, died Tuesday in Johannesburg at age 66. He had battled pancreatic cancer since 2015.

His death was announced by his manager and family spokesperson, Roddy Quin.

Clegg wrote his 1987 song “Asimbonanga” for Nelson Mandela. It became an anthem for South Africa’s freedom fighters.

Johnny Clegg was born in England, but he became one of South Africa’s most creative and outspoken cultural figures. He moved around a lot, as a white child born to an English man and a female jazz singer from Zimbabwe (then known as Southern Rhodesia). His parents split up while he was still a baby; Clegg’s mother took him to Zimbabwe before she married again, this time to a South African crime reporter, when he was 7. The family moved north to Zambia for a couple of years, and then settled in Johannesburg.

He discovered South Africa’s music when he was a young teenager in Johannesburg. He had been studying classical guitar, but chafed under its strictness and formality. When he started hearing Zulu-style guitar, he was enchanted — and liberated.

“I stumbled on Zulu street guitar music being performed by Zulu migrant workers, traditional tribesmen from the rural areas,” he told NPR in a 2017 interview. “They had taken a Western instrument that had been developed over six, seven hundred years, and reconceptualized the tuning. They changed the strings around, they developed new styles of picking, they only use the first five frets of the guitar — they developed a totally unique genre of guitar music, indigenous to South Africa. I found it quite emancipating.”

He soon found a local, black teacher — who took him into neighborhoods where whites weren’t supposed to go. He went to the migrant workers’ hostels: difficult, dangerous places where a thousand or two young men at a time struggled to survive. But on the weekends, they kicked back, entertaining each other with Zulu songs and dances.

Because Clegg was so young, he was accepted in their communities, and in those neighborhoods, he discovered his other great passion: Zulu dance, which he described as a kind of “warrior theater” with its martial-style movements of high kicks, ground stamps and pretend blows.

“The body was coded and wired — hard-wired — to carry messages about masculinity which were pretty powerful for a young, 16-year-old adolescent boy,” he observed. “They knew something about being a man, which they could communicate physically in the way that they danced and carried themselves. And I wanted to be able to do the same thing. I fell in love with it. Basically, I wanted to become a Zulu warrior. And in a very deep sense, it offered me an African identity.”

And even though he was white, he was welcomed into their ranks, despite the dangers to both him and his mentors. He was arrested multiple times for breaking the segregation laws.

“I got into trouble with the authorities, I was arrested for trespassing and for breaking the Group Areas Act,” he told NPR. “The police said, ‘You’re too young to charge. We’re taking you back to your parents.'”

He persuaded his mother to let him go back. And it was through his dance team that he met one of his longest musical collaborators: Sipho Mchunu. As a duo, they played traditional maskanda guitar music for about six or seven years.

“We couldn’t play in public,” Clegg remembered, “so we played in private venues, schools, churches, university private halls. We played a lot of embassies. We played a lot of consulates.”

Over time, they started thinking bigger; Clegg wanted to try to meld Zulu music with rock and with Celtic folk.

“I was exposed to Celtic folk music early on,” he told NPR. “I never knew my dad, and music was one way which I can connect with that country. I liked Irish, Scottish and English folk music. I had a lot of tapes and recordings of them. And my stepfather was a great fan of pipe music. On Sundays, he would play an LP of the Edinburgh Police Pipe Band.”

Clegg was sure that he heard connections between the rural music of South Africa’s Natal province (now known as KwaZulu-Natal) — the music that he was learning from his black friends and teachers — and the sounds of Britain. So Clegg and Mchunu founded a fusion band called Juluka — “Sweat” in Zulu.

At the time, Johnny was a professor of anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg; Sipho was working as a gardener. They dreamed of getting a record deal even though they knew they couldn’t get airplay, or perform publicly in South Africa.

It was a hard sell to labels. South African radio was strictly segregated, and record companies refused to believe that an album sung partly in Zulu and partly in English would find an audience in any case. Clegg told NPR that their songs’ primary subject material wasn’t setting off any sparks with record producers, either.

“You know, ‘Who really cares about cattle? You’re singing about cattle. You know we’re in Johannesburg, dude, get your subject matter right!’ Clegg recalled. “But I was shaped by cattle culture, because all the songs I learned were about cattle, and I was interested. I was saying, ‘There’s a hidden world. And I’d like to put it on the table.'”

They got a record deal with producer Hilton Rosenthal, who released Juluka’s debut album, Universal Men, on his own label, Rhythm Safari, in 1979. And the band managed to find an audience both at home and abroad. One of its songs, “Scatterlings of Africa,” became a chart hit in the U.K.

YouTube

The band toured internationally for several years, and went. But eventually, Mchunu decided he’d had enough. He wanted to go home — not just to Johannesburg, but home to his native region of Zululand, in the KwaZulu-Natal province, to raise cattle.

“It was really hard for Sipho,” Clegg told NPR. “He was a traditional tribesman. To be in New York City, he couldn’t speak English that well — there were times when I think he felt he was on Mars. And after some grueling tours, he said to me, ‘I gave myself 15 years to make it or break it in Joburg, and then go home.’ So he resigned, and Juluka came to an end —and I was still full of the fire of music and dance.”

So Clegg founded a new group called Savuka — which means “We Have Risen” in Zulu. Savuka had ardent love songs, like the swooning “Dela,” but many of the band’s tunes, like “One (Hu)Man, One Vote” and “Warsaw 1943 (I Never Betrayed the Revolution),” were explicitly political.

“Savuka was launched basically in the state of emergency in South Africa, in 1986,” Clegg observed. “You could not ignore what was going on. The entire Savuka project was based in the South African experience and the fight for a better quality of life and freedom for all.”

Long after Nelson Mandela was freed from prison and had become president of South Africa, he danced onstage with Savuka to that song that Clegg had written for him.

YouTube

Clegg went on to a solo career. But in 2017, he announced he’d been fighting cancer. And he made one last international tour that he called his “Final Journey.”

The following year, dozens of musician friends and admirers — including Dave Matthews, Vusi Mahlasela, Peter Gabriel, and Mike Rutherford of Genesis — put together a charity single to honor Clegg. It’s benefited primary school education in South Africa.

YouTube

Clegg never shied away from being described as a crossover artist. Instead, he embraced the concept.

“I love it,” he said. “I love the hybridization of culture, language, music, dance, choreography. If we look at the history of art, generally speaking, it is through the interaction of different communities, cultures, worldviews, ideas and concepts that invigorates styles and genres and gives them life and gives people a different angle on stuff that was really, just, you know, being passed down blindly from generation to generation.”

Johnny Clegg didn’t do anything blindly. Instead, he held a mirror up to his nation — and urged South Africa to redefine itself.

Once A Symbol Of Freedom, Sudan’s Pop Radio Station Has Fallen Almost Silent

“I’m trying to keep hope, because everyone is leaving, bro,” says Ahmad Hikmat, Content Director of Capital FM in Khartoum. “I am losing my team one by one.”

Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty Images

When Omar al-Bashir was ousted from the Sudanese presidency in April of 2019, there was an explosion of new culture in Sudan. In a country under strict Islamic law, suddenly, graffiti appeared on walls. Music of all kinds blasted from speakers. Men and women commingled openly at a protest camp in front of military headquarters.

Standing as a stark example of these post-military crackdown changes is Capital FM — a popular music radio station that was at the center of the spring’s cultural revolution.

“It was just so beautiful, and we were just so proud that we’re soulful,” Ahmad Hikmat, Capital FM’s content director, says as he recalls the creativity that Capital exuded. “You’d wake up in the morning, and you’d hear a song on Capital Radio was D’Angelo. Who would play D’Angelo in the morning, you know? It’s just 91.6 FM that would do that.”

But the surge of cultural awakening ended when the military junta running the country violently broke up the protests in the capital city of Khartoum. Now, Capital FM, is fighting for survival.

Now, as Hikmat walks through the empty station, the walls are bare. The sound panels have been taken down. You can still see the dabs of glue that held up vinyl records of Keith Sweat, Kenny Burke, Ray Charles and The Roots that decorated the studio.

Pushing the envelop in a Islamist country, Capital FM had become a symbol for a modern Sudan. It started as a house music station and then became a cultural hub. They had even begun hosting parties with DJs and bands where young Sudanese could quite literally let their hair down. But since the militarization of Khartoum, government censors have been taking the station off the air for hours at a time. To Hikmat, this is a clear warning sign that soon, security forces will break down Capital FM’s doors and confiscate everything — so he has started taking the place apart.

“It’s a bit dark now at the moment, because we painted the walls black because of everything that is happening,” Hikmat says.

Pushing the envelop in a Islamist country, Capital FM had become a symbol for a modern Sudan. Now, the station’s airwaves have gone almost silent.

YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP/Getty Images

Hikmat says that one of his main jobs at Capital is to keep what it represents — a utopia of progressiveness — intact. Recently, that has been a particularly difficult task. One Capital FM staffer was killed at the protest camp, and many others question whether an enterprise like Capital is even possible in Sudan at this point. “I’m trying to keep hope because everyone is leaving,” he says. “I am losing my team one by one.”

To express what he feels in respect to the situation at Capital FM and in Khartoum, Hikmat says Marvin Gaye‘s “Make Me Wanna Holler” never leaves his mind.

“For me, this is the song that plays in my mind when I am driving in the streets, just looking at the leftovers,” Hikmat says. “I see those guys, you know, sitting there, chilling with their big-a** guns, and this song just plays in my head.”

Listen to the full aired story through the audio link.

How João Gilberto’s Music Sparked An Aesthetic Revolution

João Gilberto in 1970

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

From a casual distance, the music of João Gilberto sounds like it might belong to that ancient realm known as “easy listening.”

Everything’s calm, for starters. Even at fast tempos, Gilberto’s voice demands nothing — hushed, thin, confession-booth quiet. His rhythm guitar anchors the music with accompaniment that can seem almost hypnotically repetitive. The melodies rarely beg for attention, instead basking in that sublime mix of contentedness and yearning common throughout Brazilian music. There are strings rising up in wave-like swells from time to time, and lamenting love calls from the low brass.

Beneath that smooth and pleasant veneer, Gilberto built a quiet (and still misunderstood) aesthetic revolution – a lithe, strikingly modern approach to rhythm and melody that became the blueprint for bossa nova.

Gilberto, who died at home in Rio de Janeiro on Saturday, was best known for his contributions to Getz/Gilberto, the 1964 album that, through its single “The Girl From Ipanema,” made bossa nova a worldwide sensation (and won the Grammy for album of the year). But Gilberto deserves to be remembered more broadly, as a kind of patron saint of understatement, whose early recordings transformed the boisterous celebration of samba parades into music of arresting intimacy.

The rare instrumentalist (i.e., not a composer) to define and shape a musical genre, Gilberto developed an austere, steady-handed revolution that opened up lanes of exploration for subsequent generations. And it swept like wildfire, becoming pervasive before he could even be properly acknowledged as its spark plug. (“Eventually the culture caught up to him, and despite his reputation as a recluse, he became a revered figure in Brazil — referred to as “O Mito/The Master” and “O Rei da Bossa/The King of Bossa” and “Ill Mastro Supremo,” and, perhaps most fittingly, “O Zen-Baiano/The Zen Master of Bahia.”)

YouTube

Those early recordings, particularly his 1958 take on Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Chega de Saudade/No More Blues,” had a meteor-like impact on the musicians of Brazil; Gilberto’s blend of whispering vocals and exactingly precise guitar accompaniment represented a radical break from the schmaltzy pop balladry (Nelson Gonçalves, for example) on the radio at the time. Guitarist Oscar Castro-Nieves recalled hearing that single for the first time as a teenager: “It changed everything, for every young musician in Brazil … all I can say is that it was like the first time I heard Charlie Parker.”

The singer and songwriter Caetano Veloso, another legendary Brazilian singer and songwriter whose discography elaborates on Gilberto’s basic themes, was even more effusive in an L.A. Times interview: “I owe João Gilberto everything I am today. Even if I were something else and not a musician, I would say that I owe him everything.”

Gilberto’s stealth approach was born after several unsuccessful attempts to establish himself as a musician for hire in Rio, where, according to legend (as relayed in Ruy Castro’s authoritative history of bossa nova, Chega de Saudade), he overstayed his welcome on the couches of friends. He fled to his sister’s house, in a town called Diamantina, where, in a tile bathroom with favorable acoustics, he began to experiment with a sound built around brooding, vibrato-free and leisurely, long-toned vocals.

In a rare interview with the New York Times in 1968, Gilberto explained that his process involved editing out all but the most essential information. “It has to be very quiet for me to produce the sounds I’m thinking of.”

Gilberto’s central innovation, overall, was in the guitar accompaniment. Gilberto took the massive rhythm of the samba schools he heard growing up in Bahia – a thrilling sensory experience involving hundreds of drums, superloud shakers and clanging metal bells locked together in endlessly propulsive polyrhythm – and distilled it down to stark human scale. Music centered around one voice and one acoustic guitar.

“Rosa Morena”

YouTube

Typically, such a reduction of forces diminishes — but Gilberto’s reduction had the opposite effect, opening up a new resonance for samba, using the form’s rhythmic intensity to uncover hidden directions and nuances. First, Gilberto caught the whomp of the samba bass drum with his thumb. Then, with his other fingers moving independently, he’d stab against the time with crisply articulated chords, forming an artful, unpredictable syncopation. These patterns can sound like recurring loops (Gilberto’s time is astonishingly steady) but as you listen more closely, they register as constantly evolving codes. You can hear him varying the cadences, the length of the patterns, the voicings. The result: An ever-changing, mosaic-style backdrop, a guitar-powered perpetual motion machine. (“Rosa Morena” is a good example of this.)

“Brigas, Nunca Mais”

YouTube

“Doralice”

YouTube

Over this, Gilberto sang in a placid, straightforward style that sometimes masked the turbulence underneath (as on “Brigas, Nunca Mais”), and sometimes sharpened it (as on “Doralice”). Having turned the extroversion of samba inward, he went about exploring distinct shades of emotion, adding dimension and richness to beloved early samba classics by subtracting the pageantry.

In performances and recordings from the 1970s, Gilberto began stretching out melodic phrases in whimsical, sometimes radical ways; it could be disarming to hear such a languid, vapor-like voice creating tension just by reconfiguring the commonly understood shape of a familiar melody.

Those explorations align Gilberto with artists like Bob Dylan, whose ad-libbing confounded expectations in the quest for newly resonant interpretations. More broadly, Gilberto’s austere, modernist approach connects to artistic movements outside of Brazil, most notably jazz. In both his guitar work and his singing, Gilberto was a master improviser, and his less-is-more philosophy mirrors those of Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. As they did, Gilberto pared excess language and stylistic flourishes to the bare minimum, on a quest to uncover nuances by subtraction.

As the “new” trend of bossa nova rose in the early ’60s, Gilberto became popular with a rising generation of songwriters. He introduced hundreds of songs that drew from samba while adding richly literary perspective on romance and devotion. These form the core of an extraordinary multi-generational Brazilian songbook that begins with the work of the prolific Antonio Carlos Jobim in the 1950s and ’60s, along with tunes by Veloso, Edu Lobo and others active in the late ’60s as well as stars of the ’70s like Milton Nascimento and Djavan. All of these share a common thread — the neatly syncopated performance style of Joao Gilberto. His crystalline renditions of “Corcovado” and “Caminhos Cruzados” (and countless other Jobim gems) taught subsequent generations of singers and instrumentalists how to approach the composer’s sophisticated harmonies, how to convey meaning with the slightest of gestures, how to create the kind of openness that draws the listener into the deep poignance of a tune.

The remarkable thing about João Gilberto is how often he managed this sublime art, under all kinds of musical conditions. His discography includes quietly transfixing recordings across a range of hues, from the upbeat to the meditative. And whether he’s working with a lush studio orchestra or playing alongside a lone percussionist, he rarely sounds like he’s exerting himself. Everything flows, effortlessly. He approaches the music as though sneaking or sliding into it. He’s coy, and wily, sculpting drop-dead gorgeous melodies out of shallow breath, dispensing intricate staccato samba codes with the grace of a dancer.

It is, from a distance, easy listening – the sound of serenity and calm, as steady as the sea. Let it get under your skin for a while, and the nuances blossom into complexities, the complexities breed more levels of nuance… and, pretty soon, it’s like being flattened by a feather.

João Gilberto, Master Of Bossa Nova, Dies At 88

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Updated at 9:34 p.m. on Saturday, July 6.

João Gilberto, one of the principal architects of the Brazilian musical style bossa nova, has died at his home in Rio de Janeiro, according to a FaceBook post by his son. João Marcelo Gilberto wrote that his father, who was 88 years old, died following an undisclosed illness.

João Gilberto is credited some with writing the first bossa nova, or new beat. This mid-20th century musical gift to the world drew on Brazil’s African-influenced samba tradition, but was performed without the usual battery of drums and rhythm instruments, and at much lower volumes. Gilberto’s intimate and nuanced style of guitar playing and singing, eventually central to the bossa nova sound, were reportedly developed in 1955 when he sequestered himself inside of a bathroom at his sister’s house so as not to disturb her family and to take advantage of the acoustics provided by the bathroom tiles.

In the mid-1950s, Brazil was in the midst of a post-WWII modernization inspired by a new president who wished to move the country out of third world economic status. Gilberto’s “Bim-Bom,” often named as the first bossa nova song, came from that period, and soon thereafter, the style began to sweep Rio’s cafe’s and bars. Bossa nova’s sophisticated sound became popular with a new moneyed class eager to move away from the more traditional samba sound of explosive drums and group singing. Rio de Janeiro was ground zero of the country’s cultural explosion; Gilberto, composer Antonio Carlos Jobim and poet Vinicius de Moraes were the key architects of a culture shift that forever changed their country’s musical point of reference.

The breakthrough came just before the end of the decade. In 1958 Jobim and de Moraes had collaborated on a recording of the song “Chege de Saudade” by another vocalist, but the song didn’t become a phenomenon until Gilberto’s version, with his softly percussive finger picking technique on an acoustic guitar and breathy vocals that matched the soft curves of the music. Gilberto’s version became a hit in Rio and internationally, and launched the bossa nova movement.

YouTube

Brazilian born pianist Jovino Santos Neto described the influence Gilberto’s technique had on the music of that era as profound. “His uncanny ablity to syncopate his vocal delivery, while keeping a simple groove was his trademark sound,” Neto wrote to NPR from his home in California. “Several others tried to imitate him, with no success”.

Over three years Gilberto recorded three albums that were the blueprints for a musical revolution: Chega de Saudade (Odeon, 1959), O Amor, o Sorriso e a Flor (Odeon, 1960), and João Gilberto (Odeon, 1961).

In 1961 the U.S. State Department had organized one of its goodwill musical ambassador tours to Rio and jazz guitarist Charlie Byrd caught some of the music and took the style back home, where he shared it with jazz saxophonist Stan Getz. Their 1962 album Jazz Samba was an immediate success in the US. The next year, Getz invited Gilberto to record together. The resulting album, Getz/Gilberto, featured compositions by the Jobim/de Moraes writing team, many of which became jazz standards over the decades, including “Corcovado,” “Desafinado” and “Doralice.”

The album’s breakout hit featured Gilberto’s then-wife Astrud on a sultry vocal of the song “Garota de Ipanema (Girl From Ipanema).” João sang the lyrics in Portuguese, Astrud repeated them in English and Getz added an now-iconic tenor sax solo. It was a worldwide hit and won the 1965 Grammy for record of the year. Getz/Gilberto won album of the year and would go on to become one of the highest-selling jazz albums of all time, helping to cement bossa nova’s soft, lulling beats and intimate vocals across the global musical landscape.

In the mid-1960s, less than a decade after the movement started, the music was pretty much silenced by a military dictatorship that clamped down an all outside political and cultural influences. Gilberto, who had moved to the United States after recording Getz/Gilberto, remained until 1980. Upon his return to Brazil he was heralded for his contributions and recorded with many of the younger musicians who had been part of the Tropicalia movement that incorporated rock and psychedelia into the subversive music aimed at the dictatorship.

Pianist Jovino Santos Neto says that Gilberto’s restless musical spirit was reflected in the music he made upon his return: “When people started to think that he was a bossa nova singer of Brazilian tunes, he challenged their assumptions by applying his style to boleros, Italian songs, Gershwin and later to the pop music of Brazil.”

Gilberto continued to perform well into the 21st century and has been recognized by every generation since his debut as a Brazilian musical pioneer. Well known to be a recluse, he spent the last years of his life alone in his apartment in Rio, trying to sort out various legal problems that had accumulated over the course of his storied career, while still holding a place of highest honor in his country’s cultural legacy.

The Thistle & Shamrock: Alan Reid At Swannanoa

Dr. Kathy Bullock.

Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of the artist

Scottish singer, songwriter and former Battlefield Band member Alan Reid visits Traditional Song Week at the Swannanoa Gathering. We hear highlights from his remarkable musical encounters with Cathy Jordan, Len Graham, Sheila Kay Adams, Tony Ellis, Matt Watroba and Dr. Kathy Bullock.

The Thistle & Shamrock: Singing The Land

Karine Polwart.

Reed Ingram Weir/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Reed Ingram Weir/Courtesy of the artist

This week’s show features music from Karine Polwart‘s theatrical event Wind Resistance and from fiddler Duncan Chisholm‘s Sandwood, named for the finest and least accessible beach in Scotland.