Trump Wants Insurers and Hospitals To Show Real Prices To Patients

One rule announced by the Trump administration Friday puts pressure on hospitals to reveal what they charge insurers for procedures and services. Critics say the penalty for not following the rule isn’t stiff enough to be a an effective deterrent.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Updated at 3:10 p.m. ET

President Trump has made price transparency a centerpiece of his health care agenda. Friday he announced two regulatory changes in a bid to provide more easy-to-read price information to patients.

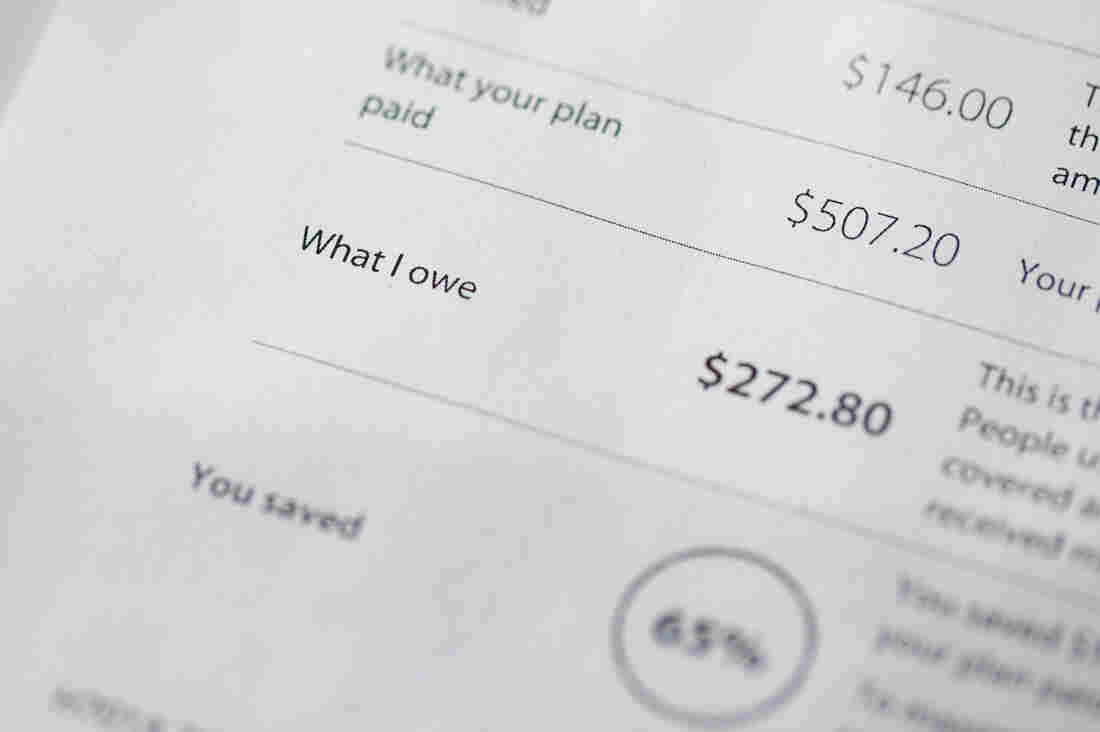

The first effort targets hospitals, finalizing a rule that requires them to display their secret, negotiated rates to patients starting in January 2021. The second is a proposal to make insurance companies show patients their expected out-of-pocket costs through an online tool. That proposed rule is subject to 60 days of public comment, and it’s unclear when it would go into effect.

“Our goal is to give patients the knowledge they need about the real price of health care services,” said Trump. “They’ll be able to check them, compare them, go to different locations, so they can shop for the highest-quality care at the lowest cost.”

Administration officials heralded both rules as historic and transformative to the health care system.

“Under the status quo, health care prices are about as clear as mud to patients,” said Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma in a written statement. “Today’s rules usher in a new era that upends the status quo to empower patients and put them first.”

As NPR has reported, hospitals are currently required to post their “list prices” online, but that information has been very hard to use and doesn’t tell consumers much about what they are likely to pay. The new rule makes hospitals show what they really pay for services — not the list prices — and requires them to make that information easy to read and easy to access.

“I don’t know if the hospitals are going to like me too much anymore with this,” Trump said in a White House news conference Friday afternoon. “That’s OK.” He later added, “We’re stopping American patients from just getting — pure and simple, two words, very simple words — ripped off. Because they’ve been ripped off for years. For a lot of years.”

The second rule Trump announced Friday (which is a proposed rule, still subject to public comments before being finalized) affects insurance companies. It would essentially make insurers give patients their “explanation of benefits” upfront. It would require insurers to explain how much a service would cost, how much your plan would pay and how much you would owe — before the service is performed. The idea is that patients could use that information to shop around ahead of time for a better deal — assuming a better deal can be found, and the service isn’t a medical emergency.

Certainly these rules would give patients more information than they currently have. The other promise of these rules — that they will bring down health care costs — is more of an open question.

In public comments for the hospital rule, hospitals argued that having to make their negotiated rates public would backfire — if a hospital is charging less than another one nearby, it could theoretically raise its price to more closely match its competitor’s.

Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar dismissed that argument on a call with reporters Friday morning.

“This is a canard,” he said. “Point me to one sector of the American economy where the disclosure of having price information in a competitive marketplace actually leads to higher prices as opposed to lower prices.”

Larry Levitt, executive vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, pointed out on Twitter that the penalty for hospitals that defy Trump’s transparency rule was “quite weak.”

“A maximum fine of $300 per day,” he wrote. “The technical term for that is ‘chump change.’ I wonder how many hospitals will just pay the fine.”

There’s also an open question about whether these rules will survive legal challenges. Another Trump administration proposal to show drug list prices in television ads was blocked in the courts.

“We may face litigation, but we feel we’re on a very sound legal footing for what we’re asking,” Azar told reporters.

NFL Suspends Myles Garrett ‘Indefinitely’ For Hitting QB With His Own Helmet

Cleveland Browns defensive end Myles Garrett hits Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Mason Rudolph with his own helmet as offensive guard David DeCastro tries to intervene, in the final seconds of their game Thursday night.

Ken Blaze/USA Today Sports / Reuters

hide caption

toggle caption

Ken Blaze/USA Today Sports / Reuters

Updated at 12:05 p.m. ET

The NFL has suspended Cleveland Browns defensive end Myles Garrett “indefinitely,” after Garrett ripped off Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Mason Rudolph’s helmet and whacked him in the head with it during a fight at the end of a game Thursday night.

Garrett won’t play again in the rest of 2019 and the postseason, the NFL announced. A date for his possible reinstatement and return won’t be set until he meets with the commissioner’s office.

“Garrett violated unnecessary roughness and unsportsmanlike conduct rules, as well as fighting, removing the helmet of an opponent and using the helmet as a weapon,” the NFL said as it announced its decision.

In response to the NFL’s move, Browns owners Dee and Jimmy Haslam sent a statement about Garrett to member station WCPN ideastream in Cleveland saying, “We understand the consequences from the league for his actions.”

The NFL also suspended Steelers center Maurkice Pouncey for three games for fighting: he punched and kicked Garrett in the aftermath of the helmet hit. And it punished the Browns’ Larry Ogunjobi with a one-game ban because he blindsided Rudolph with a hit after the quarterback had been separated from Garrett.

The league also fined all three players, but it did not disclose the amounts. The Browns and Steelers organizations were each fined $250,000.

The Haslams said they are “extremely disappointed” in the altercation. They added, “We sincerely apologize to Mason Rudolph and the Pittsburgh Steelers. Myles Garrett has been a good teammate and member of our organization and community for the last three years but his actions last night were completely unacceptable”

If Garrett’s suspension withstands an expected appeal, he would miss the Browns’ last six games. His punishment is one of the stiffest penalties for on-field behavior the NFL has ever levied, second only to that of Oakland Raiders linebacker Vontaze Burfict, who was suspended for the rest of the season in late September, with 12 games remaining.

The NFL says more disciplinary measures “will be forthcoming” for other players, including those who left their benches to join the fight.

Garrett’s actions obliterated the NFL’s boundaries of controlled violence, resulting in his immediate expulsion from Thursday night’s showcase game. The fighting also triggered shock and outrage and disbelief in the closing seconds of a game that the Browns’ defense had dominated.

YouTube

Garrett was ejected from the game along with Pouncey, who rushed in and helped take Garrett to the ground in retaliation for his attack on Rudolph. As lineman David DeCastro grappled with Garrett, Pouncey punched and kicked at his helmet. The Browns’ Ogunjobi was also ejected.

Discussing the fracas after the game, Garrett said it was “embarrassing and foolish and a bad representation of who we want to be.”

“Rivalry or not, we can’t do that. We’re endangering the other team. It’s inexcusable,” Browns quarterback Baker Mayfield said.

Garrett has emerged as a defensive star for Cleveland in his third professional year, but he has also incurred penalties at a fast rate, including two roughing-the-passer calls and an unsportsmanlike conduct foul before Thursday’s game.

The NFL has a personal safety rule forbidding “impermissible use of the helmet” — but the rulebook foresaw players using their own helmet to hit others in the course of a game, not a football player ripping an opponent’s helmet off and striking him with it.

“I made a mistake, I lost my cool,” Garrett said afterward. “And I regret it. It’s going to come back to hurt our team. The guys who jumped in the little scrum — I appreciate my team having my back, but it should never have gotten to that point. That’s on me.”

“I thought it was pretty cowardly, pretty bush league,” Rudolph said after the game. When asked how he was feeling after the violent end to a tough game, he replied, “I’m fine. I’m good, good to go.”

Before this season, the NFL’s longest suspension was a five-game ban earned by Albert Haynesworth in 2006 for removing a Dallas Cowboys player’s helmet and then stomping on his face.

After last night’s game, former Steelers linebacker James Harrison — who faced his own suspensions for dangerous hits during his career — was one of many NFL insiders who said Garrett’s actions amounted to assault.

“That’s assault at the least,” Harrison said via Twitter. He added, “6 months in jail on the street.. now add the weapon and that’s at least a year right?!”

The incident began with around 10 seconds left in the game: Garrett grabbed Rudolph as the quarterback completed a harmless third-down pass in the Steelers’ own end, stopping the game clock at 8 seconds. But after Garrett tugged and twisted Rudolph to the ground, the two began wrestling and Rudolph grasped Garrett’s helmet with both hands.

As they got up, Garrett ripped the quarterback’s helmet off by its facemask — and as DeCastro tried to intervene, Garrett swung Rudolph’s helmet in a vicious overhand arc, hitting the quarterback. As Rudolph turned to an official seeking a penalty, the Browns’ Ogunjobi leveled him from behind, sending him back down to the turf.

At the time, the Browns were leading 21-7, and their defense had already recorded four sacks and four interceptions against Rudolph’s Steelers. In the Browns’ stat sheet for the night, Garrett was notably absent from its sack list.

Going into Thursday night’s game, Garrett was leading the AFC in sacks, with 10 quarterback takedowns through the first nine games of the season. He had also been effective against the Steelers, recording four sacks and forcing three fumbles in just three games against the Browns’ division rivals.

Cleveland started the year on a wave of optimism, with talk of a possible run deep into the playoffs. But the team hasn’t lived up to those expectations. And now — instead of discussing their hopes to build on a win that brought their record to 4-6 — the Browns and Garrett are the talk of the NFL for all the worst reasons.

Prior to Garrett’s ejection, Browns safety Damarious Randall was also kicked out of Thursday night’s game, for delivering a dangerous helmet-to-helmet hit on Steelers wide receiver Diontae Johnson. But it was the end of the game that left the worst impressions in Cleveland.

“It feels like we lost,” Mayfield said afterward.

KOKOKO!: Tiny Desk Concert

Credit: Mhari Shaw/NPR

KOKOKO! are sonic warriors. They seized control of the Tiny Desk, shouting their arrival through a megaphone, while electronic sirens begin to blare. There’s a sense of danger in their sonic presence that left no doubt that something momentous was about to happen. And it did!

With instruments tied and hammered together — made from detergent bottles, scrapyard trash, tin cans, car parts, pots, pans and more — KOKOKO! managed to alter the office soundscape.

Backed by a bank of electronics, including a drum machine, this band from the Democratic Republic of the Congo redefines the norm of what music is and how music is made. Wearing yellow jumpsuits that are both utilitarian and resemble Congolese worker attire, this band from Kinshasa feel as though they’re venting frustrations through rhythm. And all the while they’re making dance music, all from their debut LP, Fongola, that feels unifying — more party than politics.

SET LIST

- “Likolo”

- “Tongos’a”

- “Malembe”

MUSICIANS

Makara Bianko: drums, vocals; Débruit: synthesizer, vocals; Boms Bomolo: bass, vocals; Dido Oweke: guitar; Love Lokombe: percussion, vocals;

CREDITS

Producers: Bob Boilen, Morgan Noelle Smith; Creative Director: Bob Boilen; Audio Engineers: Josh Rogosin, Alex Drewenskus ; Videographers: Morgan Noelle Smith, Jack Corbett, Bronson Arcuri, Maia Stern; Associate Producer: Bobby Carter; Executive Producer: Lauren Onkey; VP, Programming: Anya Grundmann; Photo: Ben De La Cruz/NPR

Amazon Appeals Pentagon’s Choice Of Microsoft For $10 Billion Cloud Contract

President Trump met with Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos as part of the American Technology Council in June 2017.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Amazon is taking the Pentagon to court. The company is alleging “unmistakable bias” on the government’s part in awarding a massive military tech contract to rival Microsoft.

This begins a new chapter in the protracted and contentious battle over the biggest cloud-computing contract in U.S. history — called JEDI, for Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure — worth up to $10 billion over 10 years.

The Pentagon declared Microsoft the winner of JEDI on Oct. 25, after months of delays, investigations and controversy — at first, over accusations of a cozy relationship between Amazon and the Department of Defense, and later, over President Trump’s public criticism of Amazon.

In a statement on Thursday, Amazon’s cloud unit argued that “numerous aspects of the JEDI evaluation process contained clear deficiencies, errors, and unmistakable bias- and it’s important that these matters be examined and rectified.” The company is appealing the contract at the U.S. Court of Federal Claims.

Amazon Web Services spokesperson said the company was “uniquely experienced and qualified” for the job, adding: “We also believe it’s critical for our country that the government and its elected leaders administer procurements objectively and in a manner that is free from political influence.”

Amazon was stunned by its loss of the JEDI contract. Microsoft’s cloud business Azure has been a distant second in size to AWS, which also previously won a cloud contract with the CIA. But a former Pentagon official familiar with the JEDI deal previously told NPR that Microsoft’s bid “hit the ball out of the park.”

A Microsoft representative did not immediately respond on Thursday. A Defense Department representative said: “We will not speculate on potential litigation.”

At stake is a high-profile project to move the American military to the cloud. The winner of JEDI, in simplest terms, would become the single manager of the process. This company would unify the Pentagon’s many disjointed networks and give U.S. war fighters access to cutting-edge computing technology like artificial intelligence anywhere in the world.

When bidding on JEDI opened in 2018, Amazon was seen as the only company that already matched the qualifications. Rival Oracle led a cantankerous lobbying campaign that accused the Pentagon and Amazon of a cozy relationship, pointing to Defense Department employees who had done work for AWS.

The Defense Department, the Government Accountability Office and the Court of Federal Claims reviewed the bidding and allowed it to proceed. Microsoft and Amazon were declared finalists. (Microsoft, Amazon, Oracle and IBM are among recent financial supporters of NPR.)

Though legally unsuccessful, rivals’ objections did grab the attention of several lawmakers in Congress and, eventually, Trump. The president has a well-known disdain toward Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, particularly over the businessman’s personal ownership of The Washington Post, whose news coverage Trump often criticizes.

In July, Trump told reporters that he was getting “tremendous complaints about the contract with the Pentagon and with Amazon; they’re saying it wasn’t competitively bid.” He said he would ask the Pentagon “to take a look at it very closely.”

Soon after, the Defense Department announced that new Secretary Mark Esper hit pause on JEDI — before unexpectedly declaring Microsoft the winner a few weeks later.

“The acquisition process was conducted in accordance with applicable laws and regulations,” the Department of Defense said in announcing the award in October. “All offerors were treated fairly and evaluated consistently with the solicitation’s stated evaluation criteria.”

NPR’s Tom Bowman contributed to this report.

How The Houston Astros Stole Signs In The 2017 Season

NPR’s Audie Cornish talks with Washington Post sports columnist Barry Svrluga about the system the 2017 Astros had for stealing signs, and how the Nationals prepped for it this year.

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

There’s a lot of noise during a baseball game, so it’s forgivable to not pick up on a particular drumbeat.

(SOUNDBITE OF DRUMMING)

CORNISH: Now, that is the sound of the Astros banging a trash can to signal an incoming pitch to their hitter during a September 2017 game. Here it is again.

(SOUNDBITE OF DRUMMING)

CORNISH: According to a story published this week by The Athletic, the Houston Astros violated rules on sign stealing. Joining us is sports columnist for The Washington Post Barry Svrluga. Welcome to the program.

BARRY SVRLUGA: Thanks for having me.

CORNISH: Let’s start with the sound itself. Who spotted it? Who realized it was a problem?

SVRLUGA: Well, a pitcher named Mike Fiers, who was on the 2017 Astros, subsequently went to other teams, told his teams that if – when they played Houston, they should be ready for pretty elaborate and technological sign stealing. He was quoted in The Athletic story that also cited three other sources saying that the Astros had this system in place and clearly a violation of MLB’s rules about using technology in the dugout.

CORNISH: Remind us what sign stealing is and why electronic stealing would be a big deal.

SVRLUGA: So sign stealing is really woven into the fabric of baseball. Players are trained to watch for differences in how a pitcher places his hands before he throws a different pitch. And then they talk about it in the dugout and say, hey, if he does this – if he comes to rest his hands at his belt, that means he’s going to throw a curveball or a change-up or a fastball. That’s all well above board.

What the Astros did here, allegedly, in installing a camera in center field to train in on the catcher’s signs of what pitch a pitcher was going to throw and then showing that in real time on a television screen in the tunnel between the dugout and the clubhouse, where the players could figure out the signs and then relay them to the batter in the batter’s box by using what The Athletic cited as a banging on a trash can – that’s considered well outside of baseball’s legal purview. So…

CORNISH: That’s incredibly elaborate, that description.

SVRLUGA: Exactly.

CORNISH: It hits both high- and low-tech – got to admire it.

SVRLUGA: Yeah, for sure. As one Nationals pitcher I talked to yesterday – the Nationals and the Astros met in the World Series last month. We don’t know whether this is true, he said. But if they won the World Series using these tactics in 2017, what’s to say that they stopped in subsequent years?

CORNISH: Let me dig into that a little more. You spoke to the Nationals pitching coach, Paul Menhart. What did he say to you about how that team prepared to play against the Astros in this year’s World Series if this was – I don’t know – an open secret in baseball?

SVRLUGA: Yeah. So – because the Astros’ reputation preceded them before the World Series this year, even before this story came out in full public view, the Nationals took some pretty extraordinary steps to use counterintelligence and offset any advantage the Astros might have been gaining.

They assigned each pitcher five different set of signs. Their two catchers had a laminated card on their wristband that showed all five sets of signs for each pitcher. The pitcher then put his sets of signs on the inside of his cap. And so if they suspected anything was going wrong, the catcher and the pitcher could get together and say we’re going to switch up our set of signs right now.

CORNISH: What does Major League Baseball have to say about all this?

SVRLUGA: So they’re conducting an investigation. They’ll certainly interview members of the 2017 world champion Astros who have since gone on to work elsewhere, both players and coaches. There are two other major league managers that are – were members of that team and staff. I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a huge fine or some sort of penalty on the Astros and some new regulations in place before spring training starts in February.

CORNISH: All right. Washington Post columnist Barry Svrluga, thanks so much.

SVRLUGA: Thanks for having me.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

University Of Memphis Defies NCAA, Tests Enforcement Of Amateurism Rules

The University of Memphis is defying the NCAA and suiting up a star freshman who has been deemed “likely ineligible.” It’s a test of the NCAA’s power to enforce longstanding amateurism rules.

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

In men’s college basketball last night, an early season matchup between top 20 teams ended with Oregon beating Memphis in Portland. But the bigger story of the game was the presence of Memphis freshman star player James Wiseman. He is right in the middle of a legal battle with the NCAA. NPR’s Tom Goldman says Wiseman’s case is generating more anger about the NCAA’s strict rules on amateurism.

TOM GOLDMAN, BYLINE: It’s not often the mere act of putting a basketball player in a starting lineup is controversial.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED ANNOUNCER: Center, 7’1″, from Nashville, Tenn., number 32, James Wiseman.

GOLDMAN: But last night, as Memphis freshman center James Wiseman jogged onto the court in Portland for pregame introductions, it was indeed a moment of significant controversy – another act of defiance, says Michael McCann. He’s a legal analyst for Sports Illustrated.

MICHAEL MCCANN: It’s a university essentially telling the NCAA, we’re doing what we want, and we’re not afraid of you.

GOLDMAN: Last week, before Memphis’ season began, the NCAA indicated Wiseman would be ineligible to play. The NCAA believed Wiseman got an improper benefit from his current head coach, Penny Hardaway. In 2017, Hardaway was a high school coach in Memphis, and he paid Wiseman’s mom a little more than $11,000 to help her move her family to Memphis, where Wiseman played high school ball for Hardaway. Years before, Hardaway had donated a million dollars to the university, his alma mater. McCann says in the NCAA’s mind, that made Hardaway a booster for the university.

MCCANN: And because of that, Wiseman is ineligible or appears to be ineligible because a player can’t have expenses paid for by a booster.

GOLDMAN: Lawyers for Wiseman argue the NCAA knew about the Hardaway payment to Wiseman’s mom when it cleared Wiseman to play in May. The attorneys rushed to a Tennessee court last Friday and got a temporary restraining order. Wiseman has played all three of Memphis’ games with support from the university and most of Memphis.

REGGIE GLASPIE: I’m a hundred percent behind him.

GOLDMAN: Forty-six-year-old Memphis resident Reggie Glaspie made the trip to Portland for last night’s game.

GLASPIE: I think Penny, number one, has the best interests of the kids, and I think that he’s doing right by trying to just let the NCAA know that, hey, you can’t pick on us.

GOLDMAN: Anti-NCAA sentiment has been percolating nationwide since late September. That’s when California passed its law allowing college athletes to be compensated for the use of their name, image and likeness, a different case than the one in Memphis, says Daily Memphian sports columnist Geoff Calkins. But really, it’s all of the same piece.

GEOFF CALKINS: People are realizing that the fundamental rules that undergird all of this are based on a system of amateurism which makes no sense. And so, sure, were – was there a violation of rules that make no sense?

GOLDMAN: The NCAA said in a statement Memphis was notified Wiseman is likely ineligible. The university chose to play him, the statement continued, and ultimately is responsible for ensuring its student athletes are eligible to play. Possible NCAA punishment could include the school forfeiting games in which Wiseman played.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED ANNOUNCER: James Wiseman.

GOLDMAN: Wiseman only played about half of last night’s game because of early foul trouble. Still, he scored 14 points, had 12 rebounds and showed the agility and power that are expected to make him one of the top NBA draft picks next year. He didn’t talk to reporters afterwards. The university is guarding him closely. For now, his lawyers are doing the talking. There’s a hearing on his case scheduled for next Monday. Two days before, Memphis plays Alcorn State and, with James Wiseman in the starting lineup, will defy the NCAA once again.

Tom Goldman, NPR News, Portland.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE MOUNTAIN HOWL’S “MELT”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Novelist Doctor Skewers Corporate Medicine In ‘Man’s 4th Best Hospital’

“The profession we love has been taken over,” psychiatrist and novelist Samuel Shem tells NPR, “with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.”

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

“Don’t read The House of God,” one of my professors told me in my first year of medical school.

He was talking about Samuel Shem’s 1978 novel about medical residency, an infamous book whose legacy still looms large in academic medicine. Shem — the pen name of psychiatrist Stephen Bergman — wrote it about his training at Harvard’s Beth Israel Hospital (which ultimately became Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) in Boston.

My professor told me not to read it, I imagine, because it’s a deeply cynical book and perhaps he hoped to preserve my idealism. Even though it has been more than 40 years since its publication, doctors today still debate whether it deserves its place in the canon of medical literature.

The novel follows Dr. Roy Basch, a fictional version of Shem, and his fellow residents during the first year of their medical training. They learn to deflect responsibility for challenging patients, put lies in their patients’ medical records and conduct romantic affairs with the nursing staff.

Basch’s friends even coin a term that is still in wide use in real hospitals today: Elderly patients with a long list of chronic conditions are still sometimes called “gomers,” which stands for “Get Out of My Emergency Room.”

Like any banned book, The House of God piqued my curiosity, and I finally read it this past year. I’m a family physician and a little over a year out of training, and I read it at the perfect time.

I got all the inside jokes about residency — and many were laugh-out-loud funny — but I am now far enough removed that the cynicism felt like satire rather than reality.

The House of God also felt dated. Basch and his cohort — who were, notably, all men, although not all white — didn’t have electronic medical records or hospital mergers to contend with. They wrote their notes about patients in paper charts. And it was almost quaint how much time the doctors spent chatting with patients in their hospital rooms.

It couldn’t be more different from my experience as a resident in the 21st century, which was deeply influenced by technology. There’s research to suggest that my cohort of medical residents spent about a third of our working hours looking at a computer — 112 of about 320 working hours a month.

In The House of God, set several decades before I set foot in a hospital, where were the smartphones? Where was the talk of RVUs — relative value units, a tool used by Medicare to pay for different medical services — or the push to squeeze more patients into each day?

That’s where Shem’s new book comes in. Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the fictional sequel to The House of God, and Basch and the gang are back together to fight against corporate medicine. This time the novel is set in a present-day academic medical center, and almost every doctor-patient interaction has been corrupted by greed and distracting technology.

Basch’s team has added a few more female physicians to its ranks, and together they battle a behemoth of an electronic medical record system. The hospital administrators in Shem’s latest book pressure the doctors to spend less time with every patient.

If The House of God is the great medical novel of the generation of physicians who came before me, perhaps Man’s 4th Best Hospital is the book for my cohort. It still has Shem’s zany brand of humor, but it also takes a hard look at forces that threaten the integrity of modern health care.

I spoke with Shem about Man’s 4th Best Hospital (which hit bookstores this week) and about his hopes for the future of medicine.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The protagonist in Man’s 4th Best Hospital, Dr. Roy Basch, doesn’t have a smartphone. I hear you don’t either. Why not?

If I had a smartphone, I would not be able to write any other novels. I have a bit of an addictive personality. I’d just be in it all the time. … I’ve got a flip phone. You can text me, but it has to be in the form of a question. I have this alphabetical keyboard. You either get an “OK” or an “N-O.”

A big theme in the novel is that technology has the potential to undermine the doctor-patient relationship. What made you want to focus on this?

I got a call out of the blue five years ago from NYU medical school. They said, “Do you want to be a professor at NYU med?” And I said, “What? Why?” And they said, “We want you to teach.” When I first got there, because I had been out of medicine [and hadn’t practiced since 1994], I figured, “Oh, I’ll look into what’s going on.” And I spent a night at Bellevue.

On the one hand, it’s absolutely amazing what medicine can do now. I remember I had a patient in The House of God [in the 1970s] with multiple myeloma. And that was a death sentence. We came in; we did the biopsy. He was dead. He was going to be dead. And that was that. Now it’s curable.

At Bellevue, I saw the magnificence of modern medicine. But like someone from Mars coming in and looking at this fresh, I immediately grasped the issues of money and effects of screens — computers’ and smartphones’.

And it just blew me away. It blew me away: the grandeur of medicine now and the horrific things that are happening to people who are really, sincerely, with love, trying to practice it. They are crunched, by being at the mercy of the financially focused system and technology.

In Man’s 4th Best Hospital, there’s a fair amount of nostalgia for the “good old days” of medicine in the 1960s and 1970s, before electronic medical records. What was better in that era?

If you ask doctors of my generation, “Why did you go into medicine?” they say, “I love the work. I really want to do good for people. I’m respected in the community, and I’ll make enough money.” Now: … “I want to have a good lifestyle.” Because you can’t make a ton of money in medicine anymore. You don’t have the respect of your community anymore. They may not even know much about you in a community because of all these [hospital] consolidations.

Do you think anything in medicine has gotten better?

The danger of isolation and the danger of being in a hierarchical system — students now are protected a lot more from that. When I was in training, interns were just so incredibly exhausted that they started doing really stupid things to themselves and patients. The atmosphere of training, by and large in most specialties, is much better.

You wrote an essay in 2002 titled “Fiction as Resistance,” about the power of novels to help make political and cultural change. What kind of resistance today can help fix American health care?

When somebody falls down, up onstage at a theater, do you ever hear the call go out, “Is there an insurance executive in the house?” No. If there are no doctors practicing medicine, there’s no health care. Doctors have to do something they have almost never done: They have to stick together. We have to stick together for what we want, in terms of the kind of health care we want to deliver, and to free ourselves from this computer mess that is driving everybody crazy, literally crazy.

Doctors don’t have a great track record of political activism, and only about half of physicians voted in recent general elections. What do you think might inspire more doctors to speak out?

Look at the difference between nurses and doctors. Nurses have great unions, powerful unions. They almost always win.

Doctors have never, ever formed anything like what the nurses have in terms of groups or unions. And that’s a big problem. So doctors somehow have to find a way — and under pressure, we might — to stick together. Doctors have to make an alliance with nurses, and other health care workers, and patients. That’s a solid group of people representing themselves in terms of what we think is good health care.

The profession we love has been taken over, with us sitting there in front of screens all day, doing data entry in a computer factory.

Health care is a big issue for the upcoming election. What kind of changes are you hoping we’ll see?

There will be some kind of national health care system within five years. … You know, America thinks it has to invent things all over again all the time. Look at Australia. Look at France. Look at Canada. They have national systems, and they also have private insurance. Don’t get rid of insurance.

The two biggest subjects for the election are health care and health care. … The bad news is, it’s really hard to get done. The good news is, I think it’s inevitable. The good news is, it’s so bad it can’t go on.

One of the major criticisms of The House of God is that it’s sexist. It seems like your hero, Dr. Basch, has gotten a little more enlightened by the time of Man’s 4th Best Hospital. Does this reflect a change you’ve also experienced personally?

I was roundly criticized for the way women were seen in The House of God.

I remember the first rotation I had as a medical student at Harvard med was at Beth Israel, doing surgery. It got to be late at night, and I was trailing the surgeon around, and he went into the on-call room. There was a bunk bed there, and he started getting ready to go to bed. And I said, “Well, I’ll take the top bunk.” And he said, “You can’t sleep here.” So I left, and in walked a nurse. I was shocked.

Things have changed, and I am very, very glad. I don’t know if it seems conscious — I was very pleased to have total gender equity in the Fat Man Clinic [where the characters in Man’s 4th Best Hospital work] by the end of the book.

What made you feel like it was time to update The House of God?

I write to point out injustice as I see it, to resist injustice, and the danger of isolation, and the healing power of good connection. … We can help our patients to get better — but nobody has time to make the human connection to go along with getting them better.

Mara Gordon is a family physician in Camden, N.J., and a contributor to NPR. You can follow her on Twitter: @MaraGordonMD.

Ethane And The Plastics Boom

America’s natural gas boom has also made it the world’s biggest exporter of ethane. It’s a building block for plastics, and U.S. gas is helping fuel the global plastics industry.

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

A boom in one industry is fueling another. For years now, the United States has been the world’s largest producer of oil and gas. That has kept natural gas prices low. And to tell you what other industry that helps, I have one word – one word – plastics. Here’s Reid Frazier of StateImpact Pennsylvania and the public radio program The Allegheny Front.

REID FRAZIER, BYLINE: Natural gas is mostly used for heating homes or fueling power plants. But it has another key ingredient you may not have heard of – ethane, a building block of plastics. President Trump brought attention to it a few months ago when he visited the site of a chemical plant Shell is building in Pennsylvania.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PEOPLE: (Chanting) U.S.A, U.S.A, U.S.A.

FRAZIER: This plant, like a number of others being built in the U.S., will convert some of the region’s ethane into plastic. Trump told workers this was bringing the country big economic benefits.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: American manufacturing. And we are reclaiming our noble heritage as a nation of builders again.

(APPLAUSE)

TRUMP: Nation of builders.

FRAZIER: But there’s so much natural gas and ethane that chemical plants in the U.S. can’t use it all. Turns out, this has been a lucky break for the European chemical company Ineos. In 2011, its own supplies of ethane from the North Sea were running low, says Warren Wilczewski, an economist with the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

WARREN WILCZEWSKI: Ineos looked at the United States where ethane supply was growing and where – especially in the Appalachian region, that ethane had, like, no place to go. And they recognized an opportunity.

FRAZIER: Ineos commissioned a fleet of ships, the first ever to carry ethane by sea, to move shale gas from a port near Philadelphia to plants in the U.K. and Norway. Ineos officials did not agree to an interview for this story, but here’s CEO Jim Ratcliffe in a company video.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

JIM RATCLIFFE: I think for some of these assets in Europe, it’s the only way they can survive. If we can bring some of the U.S. economics across to Europe…

FRAZIER: The U.S. has quickly become the world’s leading exporter of ethane, feeding growing plastics industries in India and China. And those exports are expected to keep growing. Back in 2016, it was big news when U.S. methane arrived in Scotland.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED BBC REPORTER: It is the first delivery for Ineos of shale gas into the U.K. It’s arriving at Grangemouth later this morning.

FRAZIER: And Grangemouth is home to Scotland’s biggest petrochemical plant and refinery.

KEVIN ROSS: You can see some of the flares down there, operating some of the silo towers across there, and some of the many cooling towers that are actually onsite.

FRAZIER: Kevin Ross is president of the Scottish Plastics and Rubber Association and runs a local plastics testing company. He says American shale gas has allowed Ineos to restart one of its production units. The plant is now running at full capacity. That’s not just good for the 1,300 people who work there, but for the suppliers and contractors, like him.

(SOUNDBITE OF PLASTICS LAB MACHINES WHIRRING)

ROSS: Watch your feet.

FRAZIER: At the nearby lab where his company tests plastic materials, he shows me what looks like a glossy plastic pipe.

ROSS: Almost certainly, because of what it’s made of, it’s either nuclear, pharmaceutical or military – almost certainly – because it is so expensive.

FRAZIER: So it’s a pipe?

ROSS: It is a pipe on steroids. It is a very high-performance pipe.

FRAZIER: Ineos got hundreds of millions of dollars in loan guarantees from the U.K. to retrofit the Grangemouth plant for American shale gas. But it’s also pushed for its own local supply. It wants the U.K. to allow fracking, the controversial technology that breaks up rock deep underground to get oil and natural gas. And that plan was met with intense opposition. Norman Philip, with Friends of the Earth Scotland, opposed fracking because of what he’d heard about it from communities in the U.S. and Australia.

NORMAN PHILIP: People were telling us of gas leaks. They were telling us of, like, children having headaches, and there was a toxic element of it.

FRAZIER: The pushback has resulted in an ironic twist to this story. In 2015, Scotland put in place a moratorium on fracking, and the U.K. government recently did the same. So fracking is illegal in Britain, even though it’s still legal to import shale gas produced by fracking in the U.S. Lee Sinclair is a railroad engineer at the Grangemouth petrochemical plant. He has mixed feelings about this.

LEE SINCLAIR: I think it’s a good idea, just the fact that we’re getting gas from somewhere. And the only thing I don’t like about it is Scotland said, no, well, you’re not fracking here. So they decide to go to America to get his gas.

FRAZIER: He’d rather the U.K. get a local supply. But for now, he says, America’s boom in gas and ethane is helping him keep his job. For NPR News, I’m Reid Frazier in Grangemouth, Scotland.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

How Some Online Lenders Dodge State Laws To Charge Triple Digit Interest Rates

Online lenders charging triple digit interest rates are dodging state laws banning such loans. The money is routed through banks that aren’t regulated at the state level to get around the rules.

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

Consumer watchdogs say online lenders are dodging state laws that ban very high interest rate loans, some in excess of 100%. The lenders say they’re not doing anything wrong, but advocates say these loans are predatory and are asking federal regulators to crack down. NPR’s Chris Arnold reports.

CHRIS ARNOLD, BYLINE: OK, so let’s say that I’m an online lender charging 100% interest rates. Things are working pretty well for me here. I’m making money. But then the state of California passes a new law capping interest rates for many loans much lower – at around 38%. What do I do? Well, if I can find a partner – a real bank, one that’s not subject to the state of California’s rate cap – the loan money flows through that bank – and boom – I can get around the rate cap.

LAUREN SAUNDERS: Right. I mean, this is almost like money laundering, right? This is laundering, you know, basically the source of the money and the source of the loans.

ARNOLD: That’s Lauren Saunders, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center. She says a lot of these online lenders are using what she calls rent-a-bank schemes. This lets them skirt state law because there’s no federal cap on interest rates, and most banks are not subject to the state rate caps. Saunders says this can work in different ways, but the simple version is this. The online lender does basically all the work to find the customers, approve the loans, collect on them, but right when someone gets a loan…

SAUNDERS: At the moment that the money actually goes to the consumer…

ARNOLD: That money comes from a bank that’s not covered by the interest rate limitations. So she says the online lender then immediately buys the loan back from the bank.

SAUNDERS: So it’s not really a bank loan. They’re just using banks as a fig leaf to make really high-cost loans – 160% interest – in states where those loans are illegal.

ARNOLD: Saunders says a lot more people are taking out online loans these days, and lenders are evading rate caps in 25 states. So she and 60 other consumer protection and civil rights groups have now sent letters to federal regulators, asking them to crack down. It seems clear that online lenders are evading state rate caps. On an earnings call before the California law passed, the company Elevate Credit Inc. talked about it openly. The interim CEO Jason Harvison talked about working with banks to get around rate caps.

JASON HARVISON: Similar to our recent experience in Ohio, we expect to be able to continue to serve California consumers via our bank sponsors that are not subject to the same proposed state level rate limitations.

ARNOLD: The online lenders, though, maintain that they’re not doing anything wrong. Elevate tells NPR in a statement that the letters from consumer groups, quote, “grossly mischaracterized our business and intent,” and that the company says its relationship with outside banks is in full compliance with all federal laws. So is dodging state interest rate rules illegal or just unseemly or just a creative way to keep serving your customers?

ADAM LEVITIN: We have a system right now that makes no sense.

ARNOLD: Adam Levitin is a law professor at Georgetown University. He says lawsuits in the works will likely help determine where the legal line is here. And he says Elevate, for example, does more sophisticated partnerships, which might be more legally defensible. So instead of the simple rent-a-bank scheme, in Elevate’s case – you might want to hang on to your brain here.

LEVITIN: The bank keeps the loan but sells a derivative interest in the loan – a 90% derivative interest – to a entity associated with Elevate.

ARNOLD: If that’s confusing, don’t worry. Levitin says the point is this whole complicated structure is being set up to get around the state rate cap. And he says the underlying problem is that some lenders have to play by one set of regulations, and banks get to play by another set of rules.

LEVITIN: The better way to do this really would be to have a national usury law.

ARNOLD: In other words, a nationwide rule that all lenders would have to follow. And today in Congress, lawmakers introduced a bipartisan bill to establish a national interest rate cap of 36%. Active duty military already have that protection. Some lawmakers want to extend it to the rest of the country. But plenty of financial firms are likely to lobby against it.

Chris Arnold, NPR News.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

When Countries Get Wealthier, Kids Can Lose Out On Vaccines

Mothers and their babies in Nigeria wait at a health center that provides vaccinations against polio. Vaccination rates lag in the middle-income country.

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Hannibal Hanschke/Picture Alliance/Getty Images

You’d think that as a poor country grows wealthier, more of its children would get vaccinated for preventable diseases such as polio, measles and pneumonia.

But a review published in Nature this month offers a different perspective.

“The countries that are really poor get a lot of support for the vaccinations. The countries that are really rich can afford to pay for the vaccines anyway,” says Beate Kampmann, director of the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and author of the review.

But, she says, “the middle-income countries are in a tricky situation because they don’t qualify for support, yet they don’t necessarily have the financial resources and stability to purchase the vaccines.”

Adrien de Chaisemartin, director of strategy and performance at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, agrees: “More and more vulnerable populations live in middle-income countries.” Gavi, an international nonprofit that helps buy and distribute vaccines, projects that 70% of the world’s under-immunized children will live in middle-income countries by 2030.

Brazil, India, Indonesia and Nigeria were among the 10 countries with the most children who lacked basic vaccinations in 2018 — for example, shots to prevent diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis by age 1. Each of those countries meets the World Bank’s definition of a middle-income country: an average annual income (known as the gross national income, or GNI, per capita) between $1,026 and $12,375. In Nigeria alone, 3 million kids are undervaccinated. That’s 15% of the world’s total of children who lack key vaccinations.

By contrast, vaccination rates can be high in poor countries, according to global health researchers, who say that Gavi has boosted the numbers. Rwanda, for instance, despite having a GNI of $780 per person, now has a near-universal coverage rate for childhood vaccines, on par with some of the wealthiest countries.

But in general, once a country reaches a GNI per capita threshold over $1,580 for three years, support from Gavi tapers off. And despite their improved fortunes, countries don’t always choose to fund childhood vaccines.

Angola is among the middle-income countries with the lowest vaccination rates. Diamonds and oil have helped propel the country out of low-income status, and its president is a billionaire. Yet an estimated 30% to 40% of children there did not receive basic vaccines in 2018.

The lag in vaccination rates is caused by any number of reasons. “There’s a whole list of middle-income countries, and they’re not all the same,” says Kampmann.

For example, Sam Agbo, former chief of child survival and development for UNICEF Angola, says Angola’s leadership does not fully fund immunization programs. Agbo blames a political system that he says is mired in corruption, financial mismanagement and lots of debt. So it’s hard to increase the health care budget. “Primary health care is not sexy,” he says. “People are interested in building hospitals and specialized centers rather than investing in preventive care.”

Gavi’s de Chaisemartin groups Angola with other resource-rich but corruption-plagued countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea and East Timor. “These are countries where the GNI is relatively high because of their oil resources, for the most part, but that doesn’t translate into a stronger health system,” says de Chaisemartin.

Then there’s the matter of cost. Countries that buy vaccines on the open market might pay over $100 a shot.

Public attitudes also play a role. In Brazil, which is on the high end of the middle-income spectrum, an immunization program that once outperformed World Health Organization recommendations has been declining for three years. Jorge Kalil Filho, an immunology professor at the University of Sao Paulo, says public inattention and anti-vaccine campaigns, popular on social media, are undermining progress.

De Chaisemartin says the global health community needs to adjust to an unprecedented global economic shift. “Fifteen years ago, the world was divided between poor countries, where most poor people were living, and high-income countries,” says de Chaisemartin. “Now you have a lot of middle-income countries with very poor and vulnerable populations.”