Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice Offers A Sonic Refuge

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his Party, performing live at the WOMAD festival in 1985.

Andrew Catlin/Courtesy of Real World Records

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Catlin/Courtesy of Real World Records

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was hailed as one of the singers of the 20th century. Even now, more than 20 years after his death in 1997, there’s no dearth of opportunities to hear his work, through a combination of sheer popularity, an enormous official discography, and literally thousands of pirated versions. All in all, no one has been suffering for lack for recordings of this Pakistani vocal master of qawwali, a staggeringly beautiful and ecstatic musical form.

Live at WOMAD 1985 comes out July 26 (pre-order).

Stream Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s ‘Live At WOMAD 1985’

01Allah Ho Allah Ho

21:00

02Haq Ali Ali

25:05

03Shahbaaz Qalandar

9:03

04Biba Sada Dil Mor De

9:51

And yet, here we are, with a brand-new issue of Khan captured at his vocal prime, recorded when he was just at the precipice of becoming an international phenomenon: a midnight set recorded in 1985 at England’s WOMAD festival, which was co-founded by Peter Gabriel five years earlier to showcase international music and dance talent. It was the performance that was hailed as Khan’s first real introduction to non-South Asian audiences.

It’s a recording that has languished in the archives for 34 years. (There are some low-quality videos of this performance online, but the sound on this album release, carefully digitized and remixed, is excellent.) Whether for longtime fans or new initiates, Live at WOMAD 1985 is an album to be treasured.

A bit of background for newcomers: qawwali — whose root means “utterance” in Arabic — is a uniquely South Asian musical style. These devotional songs are, in places including Pakistan and India, a core part of Sufism — that is, the mystical branch of Islam that emphasizes a personal connection to God, and embraces the qualities of tolerance, peace, and equality as core principles. (Sufi shrines and gatherings have been targeted for violence by Muslim extremists, both in South Asia and elsewhere.) As Sufism spread from Persia and what is now Turkey to northern India some 800 years ago, its poetry and music were blended with local styles.

Considering the electrifying energy that surges through a qawwali performance, the traditional set-up is rather humble. A group of performers, referred to in English as a “party” – and all male – sit cross-legged on a rug-covered stage. The main singer is usually accompanied by one or two harmoniums to provide melodic support as well as percussion (normally, the tabla and dholak drums), while a small chorus sings and provides heartbeat-like claps.

This 1985 concert marks Khan at his most traditional. It starts out with one of Khan’s signature songs: “Allah Ho” [God Is], which is also known on other recordings as “Allah Hu” or “Allah Hoo.” It’s a hamd, or praise song, and the traditional way of opening a qawwali performance. The audience was slowly drawn in, first through the plush harmonium, beautifully played by Khan’s brother, Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan, and the constant murmur of tabla and the hand claps of the group’s chorus. Those listeners couldn’t have been prepared for what was about to erupt.

Khan — who is often reverently called by the honorific Khan Sahib — was literally born into this style: his family had been qawwals for over 600 years. He learned the family business from his father and uncles — though his father, who was primarily a Hindustani (North Indian) classical singer, dreamed that his son would become a doctor.

His first public performance came at his father’s funeral, when he was just 16 years old. There was a strong adherence to classical music in his family tradition, which you can hear in Khan’s own performances. Without question, he was on fire when he sang — lovers of soul and gospel will find much common ground here. But he was also an exemplary improviser in the Hindustani classical style, using solfege-like swara syllables to race up and down the span of his range, darting between intervals large and small, and always with an ear to the technical and emotional demands of a particular raga.

At WOMAD in 1985, Khan led his neophyte listeners through a very typical qawwali performance arc: after praising God in “Allah Ho,” the group moved to “Haq Ali,” [Ali is Truth], a song devoted to the Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law (and a figure revered by Sufis of both the Sunni and Shi’a sects); “Shabaaz Qalandar,” which honors a 13th century, Afghanistan-born Sufi master; and a more contemporary love song, “Biba Sada Dil Mor De,” which opens with the line “If you can’t remain in front of my eyes, please give me back my heart.” (This style of song, called a ghazal, can be understood as a secular love song or, more mystically, as a devotee’s love of the divine.)

In all, it was a very truncated performance — in more traditional settings, qawwali concerts can go all night — but it was enough to hook listeners in.

In a qawwali performance, the main singer is usually accompanied by one or two harmoniums to provide melodic support as well as percussion, while a small chorus sings and provides heartbeat-like claps.

Jak Kilby/Courtesy of Real World Records

hide caption

toggle caption

Jak Kilby/Courtesy of Real World Records

It’s hard to overstate what a milestone this festival was for Khan. Not long after he gave this performance at WOMAD, the Pakistani artist went on to release a string of studio albums for Peter Gabriel’s tastemaking record label, Real World. (Months after his WOMAD date, he made an excellent series of live recordings in Paris for the French label Ocora, as the late anthropologist and ethnomusicologist Adam Nayyar, a friend of Khan, detailed in a lovely remembrance that he wrote after the singer’s death; around the same time, Khan also made a string of sublime live albums in London, released by the Navras label.)

Live at WOMAD 1985 offers something else, too. It’s a 30-plus-year-old album, which means that — at least for the album’s duration – it offers a sonic refuge from the world we all presently inhabit, one that’s shadowed by decades of fear, suspicion, growing nationalism and acrimony. Not only was it made many years before the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 — right after which some Pakistani immigrants to the U.S. were either deported by the government, or left the country ostensibly of their own accord — but also decades before Pakistanis in the U.S. worried about ICE raids, and a generation before racist rhetoric and heated anti-Muslim comments were part of the daily political salvos fired in the United States. Given what’s elapsed in the past three decades, it’s hard to envision a traditional, firmly Muslim artist reaching the same apex of visibility, or even popularity, in places like the U.S. or the U.K. had he emerged not in 1985, but in 2015.

In retrospect, it’s astonishing to think how beloved Khan became in such short measure. His presence in front of non-South Asian audiences lasted barely a dozen years — yet he counted among his fans Jeff Buckley, Madonna, Mick Jagger, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Eddie Vedder, with whom he recorded. Even so, pressure points around faith, identity and allegiances grew for Khan during his lifetime, and at home. He lamented the state of music, and by extension, the encroaching iron hand of a puritanical form of Islam, in his home country — a sort of fundamentalism that, if it had existed centuries earlier in South Asia, would have precluded qawwali from ever having developed in the first place.

“In Pakistan, people have an indifferent attitude towards music. There are no institutions to teach music and singing,” he told Pakistan’s Herald magazine in 1991. “[Our] people are morally confused about music. Those who want to learn or have learned are always confused and feel guilt. But to tell you the truth, classical music … is not against Islam. It is not haram [forbidden by Islamic principles].”

While his faith was rock-solid, Khan was catholic in his musical tastes; along with eventually making an array of crossover projects with European, British and North American artists, he wrote the music for and appeared in several Bollywood films, on screen or as a playback singer — the rawness smoothed out into honeyed drips of sound.

But Live at WOMAD 1985 offers pure soul — each run up and down the scale a jolt of adrenaline, each beat of the tabla drum and each handclap making the heart pound faster and louder. And this, truly, is the highest purpose of Sufi music: to bring performers and listeners alike into a state of ecstatic union with the divine. In 1993, after a concert that drew 14,000 people to New York’s Central Park, he told Time magazine: “My music is a bridge between people and God.”

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan struggled with his health for a long time, but when the end came, it came quickly. In August 1997, at just 48, he traveled from Pakistan to London for medical treatment; he was rushed straight from the airport to a hospital, where he died of a heart attack. In the 21 years since his death, a raft of younger male relatives have tried to carry Khan’s mantle, as performers of either buoyant qawwali, gauzy love songs, or treacly film tunes. But none of them have sparked the devotion of an international audience the way that Nusrat did. The Shahen-Shah, king of kings, qawwali’s brightest shining star, retains his crown.

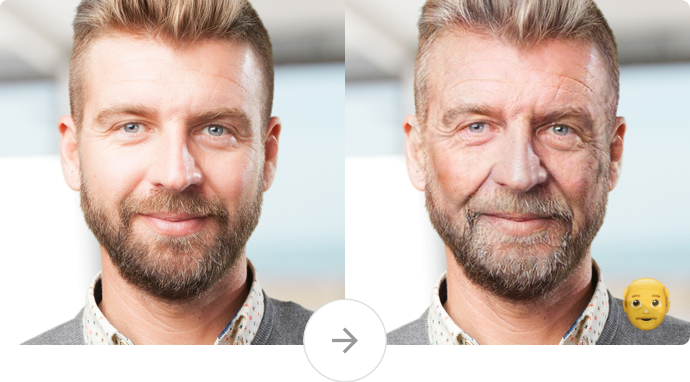

Democrats Issue Warnings Against Viral Russia-Based Face-Morphing App

The viral face-transforming FaceApp climbed to the top of the App Store on Wednesday.

FaceApp

hide caption

toggle caption

FaceApp

The growing popularity of FaceApp, a photo filter app that delights smartphone users with its ability to transform the features of any face, like tacking on years of wrinkles, has prompted Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer to call for a federal investigation into the Russia-based company over what he says are potential national security and privacy risks to millions of Americans.

“It would be deeply troubling if the sensitive personal information of U.S. citizens was provided to a hostile foreign power actively engaged in cyber hostilities against the United States,” Schumer said in a letter to the FBI and the Federal Trade Commission.

“I ask that the FTC consider whether there are adequate safeguards in place to prevent the privacy of Americans using this application, including government personnel and military service members, from being compromised,” the senator wrote.

BIG: Share if you used #FaceApp:

The @FBI & @FTC must look into the national security & privacy risks now

Because millions of Americans have used it

It’s owned by a Russia-based company

And users are required to provide full, irrevocable access to their personal photos & data pic.twitter.com/cejLLwBQcr

— Chuck Schumer (@SenSchumer) July 18, 2019

Even as privacy advocates raised security concerns, FaceApp’s mug-morphing powers lured celebrities — or anyone who had their picture saved to their phone — such as Drake and the Jonas Brothers, to try on greying hair and wrinkles. By Wednesday, FaceApp had topped Apple’s and Google’s app download charts.

Schumer’s appeal echoed concerns expressed earlier in the day from the Democratic National Committee, over fears that its artificial intelligence technology could expose vulnerable facial recognition data to a country that launched a hacking campaign against the party during the 2016 election.

The DNC has since expanded its cyber security efforts, including bringing on chief security officer Bob Lord.

In an email sent to 2020 presidential campaign staff Wednesday, Lord urged “people in the Democratic ecosystem” against using an app that could have access to its users’ photos.

“It’s not clear at this point what the privacy risks are, but what is clear is that the benefits of avoiding the app outweigh the risks,” Lord said in a notice first reported by CNN. “If you or any of your staff have already used the app, we recommend that they delete the app immediately.”

Prior to the Democratic warnings, FaceApp began responding to a flood of inquiries about whether the company stores user data and where. FaceApp told TechCrunch in a statement that while its research and development team is based in Russia, no user data is transferred there.

The company also claims that “most images are deleted from our servers within 48 hours from the upload date.”

Founder Yaroslav Goncharov told the website that FaceApp, headquartered in St. Petersburg, uses Amazon’s cloud platform and Google Cloud to host the app data, where it processes “most” photos. Uploaded photos, FaceApp said, may be stored temporarily for “performance and traffic” to ensure users don’t repeatedly upload the same photo as the platform completes an edit.

Users have expressed concerns that the app has access to their entire respective iOS or Android photo library even if the user sets photo permissions to “never.”

But FaceApp told TechCrunch that it only processes photos selected by the user — slurped from their photo library or those captured within the app. Security researchers have done their own work to back that claim. Will Strafach, a security researcher, said he couldn’t find evidence that the app uploads the camera roll to remote servers.

FaceApp also said that 99% of users don’t log in and, for that group of users, it doesn’t have access to any identifying data.

Many data privacy experts are wary about these kinds of machine-learning apps, especially in a post-Cambridge Analytica era. Last year, up to 87 million Facebook users had their personal data compromised by the third-party data analytics firm after an apparent breach of Facebook’s policy.

FaceApp’s terms of service states that it won’t “rent or sell your information to third-parties outside FaceApp (or the group of companies of which FaceApp is a part) without your consent.”

But it’s that parenthetical clause — giving leeway to an open-ended, unidentified “group of companies” — that raises a red flag for Liz O’Sullivan, a technologist at the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project and, she said, leaves the door open to another Cambridge Analytica-type scandal.

“My impression of it honestly was shock that so many people were, in this climate, so willing to upload their picture to a seemingly unknown server without really understanding what that data would go to feed,” she said.

“For all we know, there could be a military application, there could be a police application,” O’Sullivan said of FaceApp.

In the event FaceApp sells its platform to another company in the future, its privacy policy states, “user content and any other information collected through the service” are also up for grabs.

This app is one of many that leave open the potential to advance facial recognition software that, often unknown to users, is created from a compilation of people’s faces.

In many cases, O’Sullivan said, the public doesn’t find out what data is being collected about them until we see personal information revealed through Freedom of Information Act requests.

This month, as NPR has reported, researchers received records through one such request to find that Immigration and Customs Enforcement mines a massive database of driver’s license photos in facial recognition efforts that may be used to target undocumented immigrants. Researchers have concluded facial recognition technology is biased and imperfect, putting innocent people at risk.

O’Sullivan wants to see more regulation in place that’s designed to protect consumers.

Like her, many security advocates in the U.S. will be watching Europe’s testing ground as lawsuits against tech giants play out under the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, the European Union’s sweeping new data privacy law.

Opioid Epidemic ‘Road Map’ Shows 76 Billion Pills Distributed Between 2006 And 2012

NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly talks with Washington Post reporter Scott Higham about federal data that shows the scope of the opioid crisis: 76 billion pills distributed between 2006 through 2012.

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

We now have a virtual road map to the opioid epidemic, a road map that shows 76 billion opioid pills were distributed across the country between the years 2006 and 2012. That’s enough to supply every person in the United States with 36 pills each year.

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

So what this road map is is a database of information the federal Drug Enforcement Administration has collected from drug companies. The companies and the U.S. government did not want the public to see it. The Washington Post is among the newspapers that’s fought for more than a year to get this data released. And the Post’s Scott Higham joins us now. Hi, Scott.

SCOTT HIGHAM: Good afternoon.

KELLY: So what does this data tell us big-picture about the opioid crisis that we did not know before?

HIGHAM: Well, you know, this is the most comprehensive look at the opioid crisis that I think the public has ever had. It’s a database that traces the path of every single narcotic that is sold in America from manufacturer to distributor to pharmacy. And, you know, what this shows is just staggering amounts of drugs going into very small communities for the most part, places where there’s, you know, two or three thousand people. And there are millions of pills pouring into these pharmacies.

The data shows some things that we already know – that West Virginia is the epicenter, continues to be the epicenter of the pill epidemic – but there’s a lot of other things that were surprising. Nevada has been really saturated with pills. So has Tennessee, South Carolina. This is an epidemic that kind of knows no bounds, and it has just spread everywhere.

KELLY: Drug companies have blamed the epidemic on overprescribing by doctors, by pharmacists. And they have also blamed customers for abusing the drugs. Does this data challenge that narrative?

HIGHAM: Well, in some ways, it does. Look; there are corrupt doctors, and this epidemic wouldn’t have started without them. But up and down the chain, everybody has a responsibility. The doctors have a responsibility. The pharmacists have a responsibility. The distributors have a responsibility. And the manufacturers have a responsibility. It’s a tightly regulated supply chain.

And if any of those links in that chain break, the whole thing collapses. And that’s what happened. Up and down the supply chain, there were breaks, and nobody seemed to stop it. And the pills just kept pouring onto the streets of America.

KELLY: I mentioned that you fought for more than a year to get this data released. They finally gave it to you Monday night. Is that right?

HIGHAM: That’s correct. This data is part of a massive federal lawsuit. There are close to 2,000 towns, cities and counties that are suing about two dozen of these drug companies. And as part of that lawsuit, the judge allowed the parties to take a look at this previously secret database, and he allowed them to look at it under a protective order, meaning it was sealed from the public’s view.

We filed suit, saying that this is public information, and the 6th Circuit appellate court in Ohio sided with us and the Gazette-Mail, a newspaper in West Virginia, and ruled that this data should be made public.

KELLY: One striking thing here is that I’ve mentioned this is a DEA database. The government has had all this data for years – suggests they should’ve been able to spot some of these problems and take action. Did you reach out and ask them why they didn’t?

HIGHAM: Yes. The DEA said that they decline to comment because of the ongoing litigation. And when you look at this data, you understand why the DEA fought so hard to keep it secret.

Firstly, the data was such a mess when the lawyers for the plaintiffs got it, they could barely understand what was in the database because how it was constructed and maintained. And so DEA agents and others who we know within the agency have complained for years that they couldn’t use this database. They felt like the leadership of the DEA wasn’t putting enough a priority on this.

And the men and women who are in the diversion division of the DEA, which is the prescription drug division – it’s kind of a backwater at DEA. These are not the people that do the El Chapo cases, and there’s not many of them, so it’s not a high priority at the DEA, unfortunately.

KELLY: And I mentioned this is data from between 2006 and 2012, so incredibly valuable, obviously, but leaves a big, old hole in terms of what we know for the seven years since.

HIGHAM: Yes, it’s a massive hole. And, you know, we hope that, one day, you know, we’ll be able to get access to that data because I would imagine that it’s equally as revelatory and staggering in scope and its size. We’ll continue to fight for the rest of the data.

KELLY: That’s Scott Higham. He’s an investigative reporter with The Washington Post. Thank you.

HIGHAM: Thank you very much.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Teen Girl Activists Take On Skeptical Boys, Annoying Buzzwords

Activists from Girl Up. Top row from left: Valeria Colunga, Eugenie Park, Angelica Almonte, Emily Lin. Bottom row from left: Lauren Woodhouse, Winter Ashley, Zulia Martinez, Paola Moreno-Roman.

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

For Ayesha, a gender equality activist from Sierra Leone, fighting sexism means defying tradition. In her home country, girls are often married young and may be discouraged from going to school. To challenge these practices, the 19-year-old may have to stand up to a respected community leader.

“You are constantly walking on eggshells,” she says. (Plan International, which partners with Ayesha, asked that her last name not be used to protect her from backlash caused by the issues she addresses.)

She tries to find the balance between celebrating her African culture and helping other girls break away from harmful beliefs — messages that they’re not cut out for school or must fit traditional cultural definitions of femininity. Sometimes, community members see that kind of activism as a threat their way of life. But as Ayesha says, “If that’s making your girls bad, please, can I make your girls bad?”

Ayesha was one of ten young activists NPR interviewed at the Girl Up 2019 Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C., this week. Girl Up is a campaign founded by the U.N. foundation that promotes activism for 13- to 22-year-olds to work for the health, safety and education of girls.

The interviewees said it’s tough to stay involved. The girls, most of them in high school or college, feel pressure to maintain top grades while living up to their personal commitment to work for humanitarian causes. They say they have to be polite when they try to educate sexist men and boys so they don’t alienate them.

And they say they’re worn out from it all. A main theme that emerged was burnout: the physical and mental exhaustion that comes from constantly justifying their work to skeptical men.

But they’re determined to keep fighting — and find ways to de-stress (the music of Lizzo helps). Here’s what young activists are talking about this year.

What common terms do you hear in your activism that frustrate you?

Lauren Woodhouse, 18, Portland, Oregon

“Influencers.” Lauren says the term – referring to an individual with social media power — turns activism into something trendy and individualistic rather than communal. “There is fun in supporting women, but we should all recognize that any work is valuable work,” she says. “And when corporations [say that] ‘this is the influencer to follow and her feminism is our feminism,’ it’s tiring. I’m over that.”

Valeria Colunga, 18, Monterrey, Mexico

“Feminazi.” Valeria is fed up with the term because it showcases a lack of education about what feminism is. “It is tiring to have to explain it,” she says. She says many people she knows call themselves “humanists, not feminists.” So she explains that humanist and feminist “mean different things. If I have to explain it over and over again, I will do it. Because if I don’t, who will?”

Winter Ashley, 15, Gilbert, Arizona

“Young socialist.” She says she’s often seen feminism and social activism equated with socialism – especially on social media from “random, middle-aged white men [saying]: ‘you’re building a new generation of young socialists,'” she says. (And she knows that’s who’s being critical because she’s done some Facebook investigating.) “I’ve been called a young socialist in a very negative way by so many people. It’s wacky.”

Eugenie Park, 17, Bellevue, Washington

“Social justice warrior” is a term that annoys Eugenie. “When you hear the term by itself, it sounds like an empowering thing. But in reality, it’s a term that is used to minimize a lot of the work that young social justice people do” by making it seem the activists are just doing it “for a trend,” she says. That’s been discouraging for her and her friends.

When boys say you can’t do certain things, how do you react?

Hibatu, 21, Ghana

“My own brother told me when I was going to senior high school that science is not for girls and that I should pursue something much more girl-like, like the liberal arts. He told me that I am likely to be a failure or probably always be at the bottom of the class because it’s very unnatural to see girls doing so well in school. I said, that’s not true. We’ve seen other women across the continents in other places make it. And I told him, I’m going to go to school and do science, and when I finish I’m going to medical school. And I can say that I was always at the top of my class.” (Plan International, which partners with Hibatu as well as Ayesha, also asked that her last name not be used.)

Winter

“Sometimes people can be just mean, but other times they’re honestly uneducated. And we need to be able to calmly and respectfully educate someone else on why the movement [to advance women’s rights] is so important. Men are given all of the tools they need to succeed, and then women are told: ‘If you want it, make it happen.’ Like, we’re not gonna help you. And you need to give people examples of where this happens in the world and how you can see it affecting entire communities. Through education and conversation, you can at a minimum get your point across and at best, change their perspective.”

Ayesha, 19, Sierra Leone

Ayesha stresses that young activists need to remember that often people are ignorant about feminism and tied to cultural traditions like child marriage and female genital mutilation. “In this community where I come from, these [outdated ideas about gender] are things that they grew up with. So it’s not just young boys, it’s like, grown men who grew up with this norm ’cause it was drummed in their heads ever since they were little. And it’s really difficult to change someone overnight.” She says that sometimes these people are trying to be mean but often, “it’s because they really genuinely do not see [equality as] possible, because they’ve never seen it happen before. The way that you respond is what they are going to use to shape their minds. We have to constantly be able to shape this message in a language that is friendly.”

That sounds like a lot of effort and emotional labor. Do you ever burn out?

Zulia Martinez, 21, Mayagüez, Puerto Rico

A student at Wellesley College, Zulia says activist burnout is a huge problem. She’s part of an ongoing effort to convince the school to pull out of any investments in companies that sell fossil fuels. Focusing on the smaller victories gives her hope. “We had gotten so many students on board, almost the entire student body was supporting us.”

What do you do for self-care?

Ayesha

“Sometimes, as activists, you forget that you’re actually just a person. You have friends and you stress about your summer body. And you stress about your hair, and you also stress about the lives of other people. So people don’t realize that it’s difficult sometimes because you have school, and you have grades, and you have chores, and you have a family that you have to think about. And that’s why I think we really need to invest in self-care. Sometimes I tell myself just sleep well, and most importantly talk about your feelings, because this kind of work is very, very emotional.”

Paola Moreno-Roman, 29, Lima, Peru

“A lot of activists are passionate about things because we truly believe in them. But for most of us it comes from events that we went through when we were younger and that fuels and gives us energy. But I forget that there are things that we went through that we actually never addressed that we just shoved under the bed and just don’t like looking at it because it’s painful.” For her, therapy is helpful: “It goes along the lines of speaking to your friends, because if not, it can be a very lonely journey. Sometimes it just feels like you are the only one who cares. And that’s the loneliest feeling ever.”

Lauren

“Recently I got into weightlifting. It’s amazing how much more confident I feel, knowing I could start feeling different muscles that I’ve never felt before. And then I feel like I’m more physically able to defend myself and it makes me just feel like: ‘Hello, I’m here.'”

Eugenie

“I find a really big outlet for me is sports — I row crew. A lot of adolescent girls, we struggle with our body image. And something that’s really helped me is realizing that your body isn’t just there to look [socially] acceptable, societally beautiful. It’s there to serve you every day, and it’s there to pull you through a finish line. It’s there to carry you every day.”

From left, Edman Ali and Naima Yusuf, both 14, listen to a panel at the Girl Up 2019 Leadership Summit.

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Olivia Falcigno/NPR

Who’s a musical artist that keeps you inspired and energized?

Ayesha

“Beyoncé.”

Angelica Almonte, 18, Long Island, New York

“I think Lizzo is so good.”

Hibatu

“Ariana Grande!”

Emily Lin, 16, Taipei, Taiwan

“I really like Lorde and Alessia Cara. She’s like, my hero. Or she-ro.”

Speaking of “she-roes,” who are yours?

Lauren

“Ayanna Pressley was just here [at the conference.] Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, she’s like the one.”

Hibatu

“Marie Curie.”

Ayesha

“There’s a female writer, her name is Chimananda [Ngozi Adichie, Nigerian author and feminist]. I’m slightly, SLIGHTLY obsessed. I love how she balances her work with everything else that she does. I’m so in love with her.”

Angelica

“This one definitely feels a little basic, but Michelle Obama. Once I saw a picture of her [at] her great-great-great-grandmother’s tombstone.” That ancestor was a slave — “and one of her descendants becoming the first lady of the United States. That shook me.”

Zulia

“My mom. She sacrificed her career for me, and she’s the one who wanted me to become an activist. The women that surround us, empower us. And I think that’s why a lot of us have become activists.”

Valeria

“I think my girl here will be Sor Juana [Inés de la Cruz]; she’s a poet [and nun who lived and wrote in the 17th century]. She started creating poetry and art to be outspoken on issues that women were facing at that time. One specific poem talked about how men back then said that women were the ones creating their own problems. For her, it was like, how are we creating prostitution when it’s men creating demand for it? Or how do you say it’s women who are not successful when we can’t get an education?”

Any advice you have for young activists?

Winter

“One of the biggest things to remember is that activism is incredibly hard, and it takes a lot of work and a lot of perseverance. And sometimes you’ll go months without any breakthroughs. You can do all you want in the community and sometimes it’s still not going to be effective. And I think that we have to realize that that’s not a reflection of our activism. It’s not saying, oh, you’re a bad activist or what you’re doing is stupid, because it’s not. It just means that it’s going to take a little more time. And like, with myself, I am always very critical of what I’m doing; I’m not getting a breakthrough, I’m not working hard enough. And that’s not always the case. Sometimes your community isn’t ready or they’re scared of the change that you’re trying to enact. And it doesn’t happen for a really long time. Eventually, you’ll get something done. You just have to stick through.”

Luisa Torres is a AAAS Mass Media fellow at NPR. Susie Neilson is NPR’s Science Desk intern. Follow them on Twitter here: @luisatorresduq and @susieneilson

The Thistle & Shamrock: Songs Of Tannahill

Emily Smith.

Archie MacFarlane/Courtesy of the artist

hide caption

toggle caption

Archie MacFarlane/Courtesy of the artist

Hear the music and learn about the short life of 18th century poet Robert Tannahill, who wrote in the style of Robert Burns and composed well-loved songs that are still widely sung today. We feature artists Emily Smith, The Tannahill Weavers and Rod Patterson.

Pain Meds As Public Nuisance? Oklahoma Tests A Legal Strategy For Opioid Addiction

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter begins closing statements during the opioid trial at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla., on Monday, July 15. It’s the first public trial to emerge from roughly 2,000 U.S. lawsuits aimed at holding drugmakers accountable for the nation’s opioid epidemic.

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

A global megacorporation best known for Band-Aids and baby powder may have to pay billions for its alleged role in the opioid crisis. Johnson & Johnson was the sole defendant in a closely-watched trial that wrapped up in Oklahoma state court this week, with a decision expected later this summer. The ruling in the civil case could be the first that would hold a pharmaceutical company responsible for one of the worst drug epidemics in American history.

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter‘s lawsuit alleges Johnson & Johnson and its subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals helped ignite the opioid crisis with overly aggressive marketing, leading to thousands of overdose deaths over the past decade in Oklahoma alone.

The trial took place over seven weeks in the college town of Norman. Instead of a jury, a state judge heard the case.

During closing arguments Monday, Hunter called the company the “kingpin” of the opioid crisis.

“What is truly unprecedented here is the conduct of these defendants on embarking on a cunning, cynical and deceitful scheme to create the need for opioids,” Hunter said.

The state urged Judge Thad Balkman, who presided over the civil trial for seven weeks, to find Johnson & Johnson liable for creating a “public nuisance” and force the company to pay more than $17 billion over 30 years to abate the public health crisis in the state.

Driving the opioid crisis home has been a cornerstone of the Oklahoma’s lawsuit. In closing arguments Monday, one of the state’s attorneys, Brad Beckworth, cited staggering prescribing statistics in Cleveland County, where the trial took place.

“What we do have in Cleveland County is 135 prescription opioids for every adult,” Beckworth explained. “Those didn’t get here from drug cartels. They got here from one cartel: the pharmaceutical industry cartel. And the kingpin of it all is Johnson & Johnson.”

Johnson & Johnson’s attorney Larry Ottaway, rejected that idea in his closing argument, saying the company’s products, which had included the fentanyl patch Duragesic and the opioid-based pill Nucynta, were minimally used in Oklahoma.

He scoffed at the idea that physicians in the state were convinced to unnecessarily prescribe opioids due to the company’s marketing tactics.

“The FDA label clearly set forth the risk of addiction, abuse and misuse that could lead to overdose and death. Don’t tell me that doctors weren’t aware of the risks,” Ottaway said.

Defense attorney Larry Ottaway speaks for Johnson & Johnson during closing arguments. Oklahoma is asking a state judge for $17.5 billion to help pay for addiction treatment and prevention.

Sue Ogrocki/AP Photo

hide caption

toggle caption

Sue Ogrocki/AP Photo

Ottaway played video testimony from earlier in the trial, showing Oklahoma doctors who said they were not misled about the drugs’ risks before prescribing them.

“Only a company that believes its innocence would come in and defend itself against a state, but we take the challenge on because we believe we are right,” Ottaway said in his closing argument.

Johnson & Johnson fought on after settlements

Initially, Hunter’s lawsuit included Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin. In March, Purdue Pharma settled with the state for $270 million. Soon after, Hunter dropped all but one of the civil claims, including fraud, against the two remaining defendants.

Just two days before the trial began, another defendant, Teva Pharmaceuticals of Jerusalem, announced an $85 million settlement with the state. The money will be used for litigation costs and an undisclosed amount will be allocated “to abate the opioid crisis in Oklahoma,” according to a press release from Hunter’s office.

Both companies deny any wrongdoing.

The legal liability of ‘public nuisance’

Most states and more than 1,600 local and tribal governments are suing drugmakers who manufactured various kinds of opioid medications, and drug distributors. They are trying to recoup billions of dollars spent addressing the human costs of opioid addiction.

“Everyone is looking to see what’s going to happen with this case, whether it is going to be tobacco all over again, or whether it’s going to go the way the litigation against the gun-makers went,” says University of Georgia law professor Elizabeth Burch.

But the legal strategy is complicated. Unlike the tobacco industry, from which states won a landmark settlement, the makers of prescription opioids manufacture a product that serves a legitimate medical purpose, and is prescribed by highly trained physicians — a point that Johnson & Johnson’s lawyers made numerous times during the trial.

Oklahoma’s legal team based its entire case on a claim of public nuisance, which refers to actions that harm members of the public, including injury to public health. Burch says each state has its own public nuisance statute, and Oklahoma’s is very broad.

“Johnson & Johnson, in some ways, is right to raise the question: If we’re going to apply public nuisance to us, under these circumstances, what are the limits?” Burch says. “If the judge or an appellate court sides with the state, they are going to have to write a very specific ruling on why public nuisance applies to this case.”

Burch says the challenge for Oklahoma has been to tie one opioid manufacturer to all of the harms caused by the ongoing public health crisis, which includes people struggling with addiction to prescription drugs, but also those harmed by illegal street opioids, such as heroin.

University of Kentucky law professor Richard Ausness agrees that it’s difficult to pin all the problems on just one company.

“Companies do unethical or immoral things all the time, but that doesn’t make it illegal,” Ausness says.

Judge Thad Balkman listens to closing statements at the Cleveland County Courthouse. The case was a bench trial, with both sides seeking to persuade a single judge instead of a jury. Balkman is expected to issue his decision in August.

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

If the judge rules against Johnson & Johnson, Ausness says, it could compel other drug companies facing litigation to settle out of court. Conversely, a victory for the drug giant could embolden the industry in the other cases.

Earlier in the trial, the state’s expert witness, Dr. Andrew Kolodny, testified that Johnson & Johnson did more than push its own pills — until 2016, it also profited by manufacturing raw ingredients for opioids and then selling them to other companies, including Purdue, which makes Oxycontin.

“Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers have been stealing the spotlight, but Johnson & Johnson in some ways, has been even worse,” Kolodny testified.

Kolodny says that’s why the company downplayed to doctors the risks of opioids as a general class of drugs, knowing that almost any opioid prescription would benefit its bottom line.

The state’s case also focused on the role of drug sales representatives. Drue Diesselhorst was one of Johnson & Johnson’s busiest drug reps in Oklahoma. Records discussed during the trial showed she continued to call on Oklahoma doctors who had been disciplined by the state for overprescribing opioids. She even continued to meet with doctors who had patients who died from overdoses.

But Diesselhorst testified she didn’t know about the deaths, and no one ever instructed her to stop targeting those high-prescribing physicians.

“My job was to be a sales rep. My job was not to figure out the red flags,” she said on the witness stand.

The role and responsibility of doctors

Throughout the trial, Johnson & Johnson’s defense team avoided many of the broader accusations made by the state, instead focusing on the question of whether the specific opioids manufactured by the company could have caused Oklahoma’s high rates of addiction and deaths from overdose.

Johnson & Johnson’s lawyer, Larry Ottaway, argued the company’s opioid products had a smaller market share in the state compared to other pharmaceutical companies, and he stressed that the company made every effort when the drugs were tested to prevent abuse. He also pointed out that the sale of both the raw ingredients and prescription opioids themselves are heavily regulated.

“This is not a free market,” he said. “The supply is regulated by the government.”

Ottaway maintained the company was addressing the desperate medical need of people suffering from debilitating, chronic pain — using medicines regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Even Oklahoma purchases these drugs, for use in state health care services.

Next steps

Judge Thad Balkman is expected to announce a verdict in August.

If the state’s claim prevails, Johnson & Johnson could, ultimately, have to spend billions of dollars in Oklahoma helping to ease the epidemic. State attorneys are asking that the company pay $17.5 billion over 30 years, to help abate” the crisis in the state.

Balkman could choose to award the full amount, or just some portion of it, if he agrees with the state’s claim.

“You know, in some ways I think it’s the right strategy to go for the $17 billion,” Burch says. “[The state is saying] look, the statute doesn’t limit it for us, so we’re going to ask for everything we possibly can.”

In the case of a loss, Johnson & Johnson is widely expected to appeal the verdict. If Oklahoma loses, the state will appeal, Attorney General Mike Hunter said Monday.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with StateImpact Oklahoma and Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Google’s Search Bias On Trial In Washington

A Senate subcommittee is looking to see if Google is keeping conservative media and bloggers out of top search results.

Alastair Pike /AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Alastair Pike /AFP/Getty Images

Updated at 5:15 p.m. ET

Does Google have bias?

It’s the question that’s at the center of a hearing Tuesday by a Senate Judiciary subcommittee.

The hearing is probing into Google’s search engine and whether it censors conservative media and bloggers out of the top search results.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, the subcommittee chairman, called the hearing after Google failed to attend an April hearing on the topic. Facebook and Google attended.

Cruz said he’s concerned about Google’s control over what people see on the Internet, and said previous legislation passed to protect tech companies was not created to “empower large technology companies to control our speech.”

“When you submit a video, people at YouTube determine whether you’ve engaged in hate speech, an ever-changing and vague standard meant to give censorship an air of legitimacy,” Cruz said. “This is a staggering amount of power to ban speech, to manipulate search results, to destroy rivals and to shape culture.”

President Trump has alleged that big tech companies have an anti-conservative bias. On Dec. 18, 2018, the president tweeted: “Facebook, Twitter and Google are so biased toward the Dems it is ridiculous!”

Facebook, Twitter and Google are so biased toward the Dems it is ridiculous! Twitter, in fact, has made it much more difficult for people to join @realDonaldTrump. They have removed many names & greatly slowed the level and speed of increase. They have acknowledged-done NOTHING!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 18, 2018

Google has denied the claim.

“Google needs to be useful for everyone, regardless of race, nationality or political leanings,” Google’s Vice President for Government Affairs and Public Policy Karan Bhatia said at Tuesday’s hearing. “We have a strong business incentive to prevent anyone from interfering with the integrity of our products, or the results we provide to our users. Our platform reflects the online world that exists.”

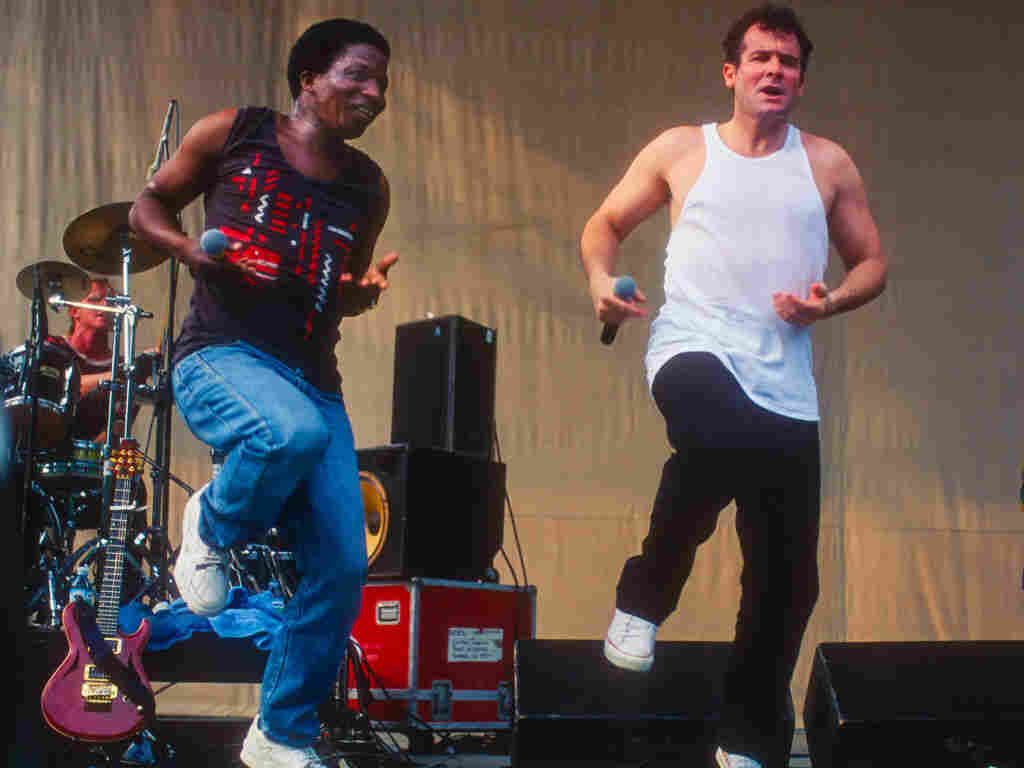

Johnny Clegg, A Uniting Voice Against Apartheid, Dies At 66

South African musician Johnny Clegg, right, with his longtime bandmate Sipho Mchunu, performing in New York City in 1996. Clegg died Tuesday at age 66.

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

One of the most celebrated voices in modern South African music has died. Singer, dancer and activist Johnny Clegg, who co-founded two groundbreaking, racially mixed bands during the apartheid era, died Tuesday in Johannesburg at age 66. He had battled pancreatic cancer since 2015.

His death was announced by his manager and family spokesperson, Roddy Quin.

Clegg wrote his 1987 song “Asimbonanga” for Nelson Mandela. It became an anthem for South Africa’s freedom fighters.

Johnny Clegg was born in England, but he became one of South Africa’s most creative and outspoken cultural figures. He moved around a lot, as a white child born to an English man and a female jazz singer from Zimbabwe (then known as Southern Rhodesia). His parents split up while he was still a baby; Clegg’s mother took him to Zimbabwe before she married again, this time to a South African crime reporter, when he was 7. The family moved north to Zambia for a couple of years, and then settled in Johannesburg.

He discovered South Africa’s music when he was a young teenager in Johannesburg. He had been studying classical guitar, but chafed under its strictness and formality. When he started hearing Zulu-style guitar, he was enchanted — and liberated.

“I stumbled on Zulu street guitar music being performed by Zulu migrant workers, traditional tribesmen from the rural areas,” he told NPR in a 2017 interview. “They had taken a Western instrument that had been developed over six, seven hundred years, and reconceptualized the tuning. They changed the strings around, they developed new styles of picking, they only use the first five frets of the guitar — they developed a totally unique genre of guitar music, indigenous to South Africa. I found it quite emancipating.”

He soon found a local, black teacher — who took him into neighborhoods where whites weren’t supposed to go. He went to the migrant workers’ hostels: difficult, dangerous places where a thousand or two young men at a time struggled to survive. But on the weekends, they kicked back, entertaining each other with Zulu songs and dances.

Because Clegg was so young, he was accepted in their communities, and in those neighborhoods, he discovered his other great passion: Zulu dance, which he described as a kind of “warrior theater” with its martial-style movements of high kicks, ground stamps and pretend blows.

“The body was coded and wired — hard-wired — to carry messages about masculinity which were pretty powerful for a young, 16-year-old adolescent boy,” he observed. “They knew something about being a man, which they could communicate physically in the way that they danced and carried themselves. And I wanted to be able to do the same thing. I fell in love with it. Basically, I wanted to become a Zulu warrior. And in a very deep sense, it offered me an African identity.”

And even though he was white, he was welcomed into their ranks, despite the dangers to both him and his mentors. He was arrested multiple times for breaking the segregation laws.

“I got into trouble with the authorities, I was arrested for trespassing and for breaking the Group Areas Act,” he told NPR. “The police said, ‘You’re too young to charge. We’re taking you back to your parents.'”

He persuaded his mother to let him go back. And it was through his dance team that he met one of his longest musical collaborators: Sipho Mchunu. As a duo, they played traditional maskanda guitar music for about six or seven years.

“We couldn’t play in public,” Clegg remembered, “so we played in private venues, schools, churches, university private halls. We played a lot of embassies. We played a lot of consulates.”

Over time, they started thinking bigger; Clegg wanted to try to meld Zulu music with rock and with Celtic folk.

“I was exposed to Celtic folk music early on,” he told NPR. “I never knew my dad, and music was one way which I can connect with that country. I liked Irish, Scottish and English folk music. I had a lot of tapes and recordings of them. And my stepfather was a great fan of pipe music. On Sundays, he would play an LP of the Edinburgh Police Pipe Band.”

Clegg was sure that he heard connections between the rural music of South Africa’s Natal province (now known as KwaZulu-Natal) — the music that he was learning from his black friends and teachers — and the sounds of Britain. So Clegg and Mchunu founded a fusion band called Juluka — “Sweat” in Zulu.

At the time, Johnny was a professor of anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg; Sipho was working as a gardener. They dreamed of getting a record deal even though they knew they couldn’t get airplay, or perform publicly in South Africa.

It was a hard sell to labels. South African radio was strictly segregated, and record companies refused to believe that an album sung partly in Zulu and partly in English would find an audience in any case. Clegg told NPR that their songs’ primary subject material wasn’t setting off any sparks with record producers, either.

“You know, ‘Who really cares about cattle? You’re singing about cattle. You know we’re in Johannesburg, dude, get your subject matter right!’ Clegg recalled. “But I was shaped by cattle culture, because all the songs I learned were about cattle, and I was interested. I was saying, ‘There’s a hidden world. And I’d like to put it on the table.'”

They got a record deal with producer Hilton Rosenthal, who released Juluka’s debut album, Universal Men, on his own label, Rhythm Safari, in 1979. And the band managed to find an audience both at home and abroad. One of its songs, “Scatterlings of Africa,” became a chart hit in the U.K.

YouTube

The band toured internationally for several years, and went. But eventually, Mchunu decided he’d had enough. He wanted to go home — not just to Johannesburg, but home to his native region of Zululand, in the KwaZulu-Natal province, to raise cattle.

“It was really hard for Sipho,” Clegg told NPR. “He was a traditional tribesman. To be in New York City, he couldn’t speak English that well — there were times when I think he felt he was on Mars. And after some grueling tours, he said to me, ‘I gave myself 15 years to make it or break it in Joburg, and then go home.’ So he resigned, and Juluka came to an end —and I was still full of the fire of music and dance.”

So Clegg founded a new group called Savuka — which means “We Have Risen” in Zulu. Savuka had ardent love songs, like the swooning “Dela,” but many of the band’s tunes, like “One (Hu)Man, One Vote” and “Warsaw 1943 (I Never Betrayed the Revolution),” were explicitly political.

“Savuka was launched basically in the state of emergency in South Africa, in 1986,” Clegg observed. “You could not ignore what was going on. The entire Savuka project was based in the South African experience and the fight for a better quality of life and freedom for all.”

Long after Nelson Mandela was freed from prison and had become president of South Africa, he danced onstage with Savuka to that song that Clegg had written for him.

YouTube

Clegg went on to a solo career. But in 2017, he announced he’d been fighting cancer. And he made one last international tour that he called his “Final Journey.”

The following year, dozens of musician friends and admirers — including Dave Matthews, Vusi Mahlasela, Peter Gabriel, and Mike Rutherford of Genesis — put together a charity single to honor Clegg. It’s benefited primary school education in South Africa.

YouTube

Clegg never shied away from being described as a crossover artist. Instead, he embraced the concept.

“I love it,” he said. “I love the hybridization of culture, language, music, dance, choreography. If we look at the history of art, generally speaking, it is through the interaction of different communities, cultures, worldviews, ideas and concepts that invigorates styles and genres and gives them life and gives people a different angle on stuff that was really, just, you know, being passed down blindly from generation to generation.”

Johnny Clegg didn’t do anything blindly. Instead, he held a mirror up to his nation — and urged South Africa to redefine itself.

What Did Wimbledon Teach Us About Genius?

Matthias Hangst/Getty Images

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt of Planet Money’s newsletter. You can sign up here.

Sunday’s tennis championship at Wimbledon between Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer lasted nearly five hours, a record. It finished with a 12-12 tie in the final set, triggering a first-to-seven tiebreaker. For tennis fans, it was an epic struggle between legends in a storybook setting. The weather was perfect, and the hats were divine. For readers of David Epstein’s new book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, however, it was an academic nail-biter, a test case in a simmering war between specialists and generalists.

Range argues that professional success in most fields is not primarily the product of intense specialization but of generalization, of the cross-pollination of ideas and experiences. Range is an ode to late starters, like Vincent van Gogh, who wandered Europe and failed at all kinds of things, including preaching, before changing the art of painting. It’s about the NASA scientists who failed to prevent the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle, because they couldn’t operate outside the discipline of their training. It extols violinists who start late and polymaths like Charles Darwin.

Epstein is also the author of The Sports Gene, about genetics and outcomes in athletics. Taken together, The Sports Gene and Range form something like a rebuttal to Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and the whole gospel of the 10,000 hours, which suggests that mastery can be achieved only through consistent, unwavering focus. (The two authors, in their own classic bout, actually spent a lecture arguing about generalization and specialization at a sports conference this year. You can watch it here.) Range, like Outliers, is a book about ideas, success and brilliance, and both books rely on zillions of academic studies.

And it’s about sports, of course, our most measured form of success, with a stop on the tennis court. The book opens with a story about Federer, who is described as the antithesis of Tiger Woods. (Epstein says he titled his book proposal Tiger vs. Roger.) Tiger Woods played nothing but golf, starting at around 2 years old. Federer, Epstein writes, was raised on a variety of sports. His mother specifically discouraged him from specializing in tennis. He was steered away from playing more competitive matches so he could hang out with his friends. His mother often didn’t even watch him play.

Increasingly, writes Epstein, research about sports in particular and many fields in general is finding that early specialization more often leads to burnout and skill mismatches than success. The better path, statistically, is early and wide “sampling.” It matches people to the best skills. It allows disciplines to inform one another. The numbers suggest this is true for most professional athletes, and, of course, we all want it to be true. Specialization is grueling, relentless and not really that charming.

But!

Djokovic won. Beat Federer at the end of five hours by one point.

And Djokovic is a specialist, in its most extreme form. There are no accounts of Djokovic dabbling, testing a bunch of different sports. A child prodigy, he picked up tennis at 4 and never strayed. At 7, he was interviewed for a television spot in Serbia. “Tennis is my job,” he said, according to Sports Illustrated. “My goal in tennis is to become No. 1.” He had no other interests.

Bummer. But, still, Range is a delight to read because it tells us what we want to learn: that aimlessness is the path to greatness, that our distractibility is not our weakness but our secret power, that genius and perfection can show up for us with luck, as long as we’re just willing to amble around enough.

And you could hear that wish in the crowd, which was cheering for the lovely-to-watch Federer. No one wants to be Djokovic, the anxiety-ridden grinder. But he does seem to win a lot.

If you’d just finished Range and were pumped to dabble, and maybe get started on greatness later, Wimbledon was a real heartbreaker.

Did you enjoy this newsletter? Well, it looks even better in your inbox! You can sign up here.

Trump Taps Health Care Expert As Acting Top White House Economist

President Trump has named Tomas Philipson as acting chair of his Council of Economic Advisers. Philipson, who is already a member of the council, is a University of Chicago professor who specializes in the economics of health care.

He previously served as a top economist at the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Philipson takes over from White House economist Kevin Hassett, whose departure was announced on Twitter last month.

“I want to thank Kevin for all he has done,” Trump tweeted. “He is a true friend!”

“I’m leaving on very good terms with the president,” Hassett said in an interview. He stressed that two years is a typical tenure for CEA leaders, many of whom come to the White House on loan from universities.

“One of the reasons why CEA has stayed an objective resource over all these years is that the chairmen have tended to turn over after a couple of years, which is not really enough time to go native,” Hassett said. “If you stay here too long, then you might end up being too fond of all the political types over in the West Wing and it might be a little bit harder to tell them the difficult truths.”

Hassett, a sunny optimist who co-authored the book Dow 36,000 at the height of the dot-com bubble, hasn’t felt the need to tell many difficult truths. While many forecasters predict a slowdown in the U.S. economy this year, Hassett continues to project economic growth of at least 3%.

Colleagues describe Philipson as a top-notch economist and a creative problem-solver.

“Tom is a very fresh thinker,” said Mark McClellan, a veteran of the George W. Bush administration who recruited Philipson to work for him, first at the FDA and later at CMS. “Tom had a great background in health economics and wanted to do work that was very policy relevant. So it was a win-win.”

Although Philipson grew up in Sweden, where the vast majority of health care costs are covered by the government, he stresses market-oriented reforms and consumer choice.

“Coming from the University of Chicago, it’s probably not surprising that as an economist he would envision a big role for consumers in improving how markets function,” McClellan said. “I would emphasize as well, though, that he has a good understanding of government institutions and the role of regulation.”

At the FDA, McClellan said, Philipson helped institute a system in which drugmakers and medical device manufacturers paid higher fees to facilitate faster approvals. At CMS, he worked on Medicare Advantage — a program that allows about a third of Medicare recipients to get their benefits through private insurers.