A 2010 photo of Father Yeznig Zegchanian of Forty Martyrs Armenian Apostolic Church in Aleppo, Syria. Jason Hamacher hide caption

itoggle caption Jason Hamacher

An American punk drummer has become an unlikely historian of the Armenian community in Aleppo, Syria. And he’s recently released a recording of their religious music — just as the city is crumbling during Syria’s ongoing civil war.

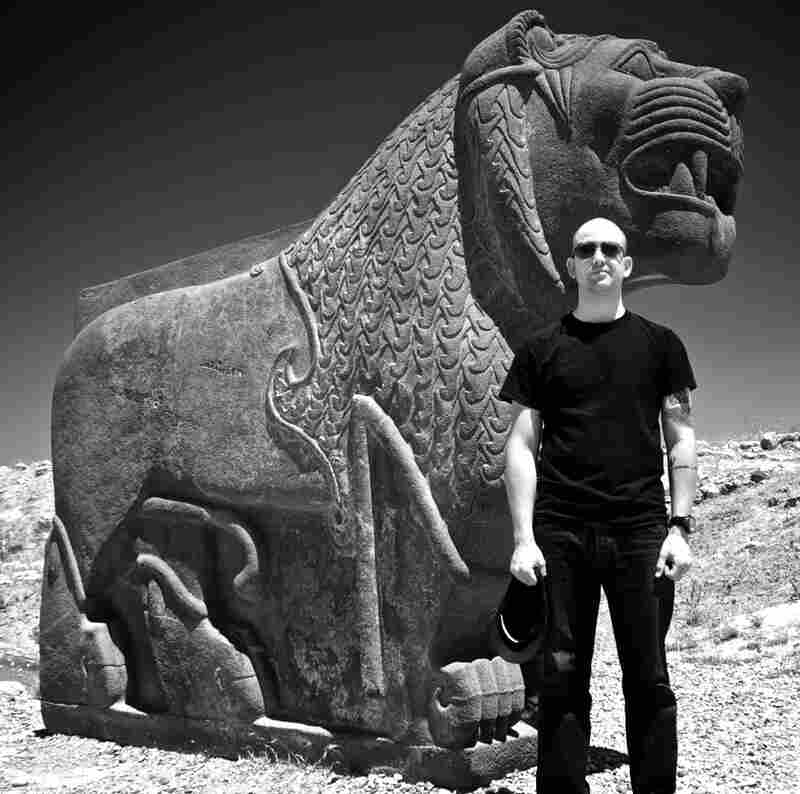

Archivist Jason Hamacher at the archaeological site of Ain Dara, Syria, in 2010. Courtesy of Jason Hamacher hide caption

itoggle caption Courtesy of Jason Hamacher

Jason Hamacher doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who would be drawn to a place like Syria.

“I am the son of a Southern Baptist minister,” he says. “I was born in Texas, I have no cultural ties or blood ties whatsoever to the Middle East, or to the populations that inhabit the Middle East.”

Back in the early 2000s, Hamacher was a punk drummer in Washington, D.C., playing in several hardcore bands. A little musical competition between friends changed the direction of his whole life.

“We each challenged ourselves, saying each person has to find something online that we could write music to, and report back to each other,” he says. “So a couple of days later, a friend of mine calls, and said, ‘Hey. I found this really amazing chant from Serbia that you should check out.’ It was a bad phone connection, and I completely misunderstood him and thought he said ‘Syria.'”

He wasn’t a trained musicologist or photographer. But beginning in 2006, he made several trips to Syria, taking photos and recording music he found along the way. He documented many of Syria’s diverse minority communities, including Jews, Sufi Muslims and several different Christian denominations. He’s been releasing those recordings, one by one, on his own label.

His most recent release is an album that Hamacher made at a 15th-century Armenian church in Aleppo. It’s just one priest, Yeznig Zegchanian, chanting.

“It’s the famed Forty Martyrs church, and it’s the actual voice inside the church, which is what really makes the album so special,” Hamacher explains. “The songs are common songs. They can be heard throughout the liturgical year. There’s nothing rare about the songs.”

But the church and its neighborhood are another matter. The Armenian neighborhood of Judayda was a place where everybody went. It’s full, Hamacher says, of “really windy back alleys, and it opens up onto this really amazing square that’s lined with restaurants, trees and silver shops.”

“It was always one of those magical places where you had multiple communities living together, says Elyse Semerdjian, a historian of Syria at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash. “From neighborhood to neighborhood, you could switch languages, from Armenian to Kurdish to Turkish to Arabic.”

Semerdjian comes from an Armenian family from Aleppo, and she wrote the liner notes for Zegchanian and Hamacher’s Forty Martyrs: Armenian Chanting from Aleppo. She says the city became important to Armenians many centuries ago, because of Armenia’s religious heritage. Armenia officially became a Christian country 1700 years ago, in the year 301.

“You know, Aleppo was always situated along a pilgrimage route to Jerusalem,” she says. “And so we have very early accounts of Armenians who passed through Aleppo, and stayed in Aleppo for a period of time.”

Semerdjian says that Aleppo became even more of a refuge after 1915, when up to a million and a half Armenians were killed or deported from the Ottoman Empire.

“When the Armenian genocide took place in 1915,” Semerdjian says, “Aleppo was one of the major deportation routes for Armenians, where, on what were, in effect, death marches, that people were very lucky to survive. If they survived them at all, they ended up, many of them, in Aleppo.”

Father Zegchanian was born in Aleppo. He was first recorded by Jason Hamacher in 2006. Hamacher returned to Forty Martyrs four years later to try to record him again. But a deacon refused to even let him speak to Father Zegchanian until the priest himself happened to walk by — and Hamacher chased after him.

“It’s like, ‘I don’t know if you remember me,'” Hamacher recounts. “‘I would love to record an record with you inside the church. He’s like, ‘OK.'”

“‘Oh, that’s great!'” Hamacher continues. “And then he just started walking into the church. I was like, ‘Wait, not now, I don’t have my stuff!’ He’s like, ‘Yes.’ I was like, ‘Yes, you’ll do it? Or … yes to later?’ It’s like, ‘OK … let me go get my equipment!'”

And that recording, made totally on the fly, became an important historical document of an Aleppo that is nearly gone. In April of this year, the church of Forty Martyrs was bombed.

“At first, it seemed that the church, and everything related to the church, was completely destroyed,” Hamacher says. “And fortunately, it turned out to just be the courtyard and complex related to the church.”

Hamacher hasn’t been able to contact Father Zegchanian in the past couple of years. And he hasn’t been able to go back to Syria because of the war — but he says that’s made his work all the more urgent.

“Major portions of the iconic symbolism of that city has been wrecked and destroyed,” Hamacher says emphatically. “The importance to continue at least the memory of these places is to keep the arts going. That’s my attempt, you know, that’s my contribution, is trying to represent these communities in a way that is informational, respectful, artistic and honorable.”

In the meantime, Hamacher is eager to share what he’s collected. He’s working on a book of photos from Aleppo, and says that he’ll be releasing an album a year of music from Syria, as long as he’s got material.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.