By Emma Bowman

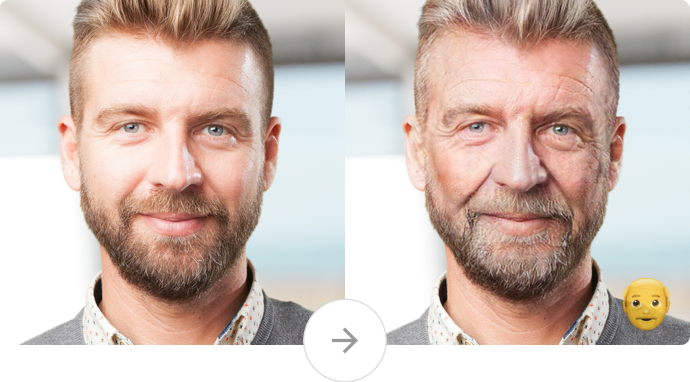

The viral face-transforming FaceApp climbed to the top of the App Store on Wednesday.

FaceApp

hide caption

toggle caption

FaceApp

The growing popularity of FaceApp, a photo filter app that delights smartphone users with its ability to transform the features of any face, like tacking on years of wrinkles, has prompted Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer to call for a federal investigation into the Russia-based company over what he says are potential national security and privacy risks to millions of Americans.

“It would be deeply troubling if the sensitive personal information of U.S. citizens was provided to a hostile foreign power actively engaged in cyber hostilities against the United States,” Schumer said in a letter to the FBI and the Federal Trade Commission.

“I ask that the FTC consider whether there are adequate safeguards in place to prevent the privacy of Americans using this application, including government personnel and military service members, from being compromised,” the senator wrote.

BIG: Share if you used #FaceApp:

The @FBI & @FTC must look into the national security & privacy risks now

Because millions of Americans have used it

It’s owned by a Russia-based company

And users are required to provide full, irrevocable access to their personal photos & data pic.twitter.com/cejLLwBQcr

— Chuck Schumer (@SenSchumer) July 18, 2019

Even as privacy advocates raised security concerns, FaceApp’s mug-morphing powers lured celebrities — or anyone who had their picture saved to their phone — such as Drake and the Jonas Brothers, to try on greying hair and wrinkles. By Wednesday, FaceApp had topped Apple’s and Google’s app download charts.

Schumer’s appeal echoed concerns expressed earlier in the day from the Democratic National Committee, over fears that its artificial intelligence technology could expose vulnerable facial recognition data to a country that launched a hacking campaign against the party during the 2016 election.

The DNC has since expanded its cyber security efforts, including bringing on chief security officer Bob Lord.

In an email sent to 2020 presidential campaign staff Wednesday, Lord urged “people in the Democratic ecosystem” against using an app that could have access to its users’ photos.

“It’s not clear at this point what the privacy risks are, but what is clear is that the benefits of avoiding the app outweigh the risks,” Lord said in a notice first reported by CNN. “If you or any of your staff have already used the app, we recommend that they delete the app immediately.”

Prior to the Democratic warnings, FaceApp began responding to a flood of inquiries about whether the company stores user data and where. FaceApp told TechCrunch in a statement that while its research and development team is based in Russia, no user data is transferred there.

The company also claims that “most images are deleted from our servers within 48 hours from the upload date.”

Founder Yaroslav Goncharov told the website that FaceApp, headquartered in St. Petersburg, uses Amazon’s cloud platform and Google Cloud to host the app data, where it processes “most” photos. Uploaded photos, FaceApp said, may be stored temporarily for “performance and traffic” to ensure users don’t repeatedly upload the same photo as the platform completes an edit.

Users have expressed concerns that the app has access to their entire respective iOS or Android photo library even if the user sets photo permissions to “never.”

But FaceApp told TechCrunch that it only processes photos selected by the user — slurped from their photo library or those captured within the app. Security researchers have done their own work to back that claim. Will Strafach, a security researcher, said he couldn’t find evidence that the app uploads the camera roll to remote servers.

FaceApp also said that 99% of users don’t log in and, for that group of users, it doesn’t have access to any identifying data.

Many data privacy experts are wary about these kinds of machine-learning apps, especially in a post-Cambridge Analytica era. Last year, up to 87 million Facebook users had their personal data compromised by the third-party data analytics firm after an apparent breach of Facebook’s policy.

FaceApp’s terms of service states that it won’t “rent or sell your information to third-parties outside FaceApp (or the group of companies of which FaceApp is a part) without your consent.”

But it’s that parenthetical clause — giving leeway to an open-ended, unidentified “group of companies” — that raises a red flag for Liz O’Sullivan, a technologist at the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project and, she said, leaves the door open to another Cambridge Analytica-type scandal.

“My impression of it honestly was shock that so many people were, in this climate, so willing to upload their picture to a seemingly unknown server without really understanding what that data would go to feed,” she said.

“For all we know, there could be a military application, there could be a police application,” O’Sullivan said of FaceApp.

In the event FaceApp sells its platform to another company in the future, its privacy policy states, “user content and any other information collected through the service” are also up for grabs.

This app is one of many that leave open the potential to advance facial recognition software that, often unknown to users, is created from a compilation of people’s faces.

In many cases, O’Sullivan said, the public doesn’t find out what data is being collected about them until we see personal information revealed through Freedom of Information Act requests.

This month, as NPR has reported, researchers received records through one such request to find that Immigration and Customs Enforcement mines a massive database of driver’s license photos in facial recognition efforts that may be used to target undocumented immigrants. Researchers have concluded facial recognition technology is biased and imperfect, putting innocent people at risk.

O’Sullivan wants to see more regulation in place that’s designed to protect consumers.

Like her, many security advocates in the U.S. will be watching Europe’s testing ground as lawsuits against tech giants play out under the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, the European Union’s sweeping new data privacy law.