With Blackouts, California’s Electric Car Owners Are Finding New Ways To Charge Up

Clarence Dold used his 2013 Nissan Leaf to power his house during a four-day blackout in Santa Rosa, Calif., as a result of the Kincade Fire.

NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR

Lawrence Levee’s evacuation call came at 4 a.m. The Getty fire was just a few miles away. He and all of his Mandeville Canyon neighbors needed to evacuate.

He grabbed what he could and threw it into his bright blue electric Chevy Bolt. His car battery was only charged halfway, but that left him with plenty of power to make a quick getaway and then some.

But after driving around the next day, running errands in an area he didn’t know well, he was in a pickle. He couldn’t find a charging station. And he had 25 miles left to his tank.

“Where are the cheap charging stations?” Levy asked a Facebook group for Bolt owners, where members have been talking about how to charge up in a disaster situation.

Levee is one of hundreds of thousands of electric car drivers in California, many of whom are caught in a state-wide struggle for electric power. As flames rip through rural and urban areas, utilities are cutting about a million customers off the grid. The blackouts sometimes last for days at a time, forcing some electric car owners to find alternative ways to charge up.

It’s an ironic conundrum in a state that’s home to more electric cars than any other other. California has just under half of the electric cars in sold in the U.S., according to EV Volumes, a group that tracks electric car sales.

In Levee’s case, he didn’t expect to be away from his house for so long. Normally, he’d pull into his garage and connect to a solar-powered battery. But that was impossible. Instead, he tried to hit up a nearby public charger that he remembered driving past a couple of times. But when he got there, it was broken.

Dreaded “range anxiety” set in. If he didn’t plug in soon, he could end up stranded.

But his trusty Bolt Facebook group came to the rescue. That’s where electric car fans commiserate, offer advice and do the occasional gas-car-driver bashing. Lately, they’ve been talking about blackouts. They pointed him to an app, and he found a free charger at a mall a few miles away.

Levee has only owned his Bolt for eight months, and already he says he’ll “never go back to a regular car.” Despite the brief inconvenience and the fire evacuations that are in his future, he notes California has better electric car infrastructure than any other state, with 18,000 public charging stations, according to the California Energy Commission.

And some electric car owners are taking advantage of these charging stations in new ways.

Clarence Dold lives in Sonoma County, which had been ravaged by the Kincade fire. Dold owns a 2013 Nissan Leaf and was left without power for four days.

But Dold found an ingenious use for his car: as a generator to power his house.

All it took was a pair of jumper cables that he connected to the Leaf’s battery and an inverter about the size of a dictionary. The inverter box changes direct current (DC) power, the kind that powers electric cars, into alternating current (AC), the electrical current that powers homes.

After that, he ran a series of heavy duty extension cords into the main rooms of his ranch house. Throughout the blackout, Dold said, “were watching TV, and had a cold fridge and a couple of lights and things seemed normal.”

The whole thing cost about $200 — a fraction of the price of a generator, which can run thousands of dollars.

Every few hours, Dold said, he’d make his way back into the car to check the battery gauge. He wanted to make sure the house wasn’t depleting the car of too much power. If it did, he’d disconnect the cables and drive 5 miles away to recharge at a public charging station.

“The power outages are not over a broad area; this isn’t like a hurricane hitting Florida,” he explained.

During the blackout, the rest of the neighborhood was a cacophony of gas and electric generator rumblings. Meanwhile, his Nissan Leaf was virtually silent.

For Dold, and other enterprising electric car owners like him, that’s the secret sauce to surviving what’s becoming the new normal in California.

Nike To Investigate Runner Mary Cain’s Claims Of Abuse At Its Oregon Project

Mary Cain says she endured constant pressure to lose weight and was publicly shamed during her time at the Nike Oregon Project. She’s seen here in the 1500-meter race at the 2014 USA Track and Field Championships. Cain won silver in that race; she had turned 18 just a month earlier.

Christopher Morris /Corbis via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Morris /Corbis via Getty Images

Nike says it’s investigating claims of physical and mental abuse in its now-defunct Oregon Project in response to former running phenom Mary Cain’s harrowing account of her time under disgraced coach Alberto Salazar.

Cain says she paid a steep price during her time with the elite distance-running program, from self-harm and suicidal thoughts to broken bones related to her declining health.

She is speaking out less than a month after Nike shut down the Oregon Project in the wake of a four-year doping ban against Salazar, which he has said he plans to appeal. A string of elite athletes — Cain’s former Oregon Project teammates — say they back her claims.

“I joined Nike because I wanted to be the best female athlete ever,” Cain says in an opinion video produced by The New York Times. “Instead, I was emotionally and physically abused by a system designed by Alberto and endorsed by Nike.”

Cain, 23, shot to fame in 2012 as a blazingly fast New York teenager who shattered national records. She began training with Salazar full time after finishing high school, skipping the NCAA track circuit altogether. At the time, she was seen as a prodigy, a sure bet to win Olympic gold and set world records. In 2013, she won the International Athletic Foundation’s Rising Star Award.

But Cain says that Salazar and other staff members constantly pressured her to lose weight — and that her health suffered dramatically as a result.

“When I first arrived, an all-male Nike staff became convinced that in order for me to get better, I had to become thinner and thinner and thinner,” Cain says in the Times video.

Cain says that mantra — and public shaming about her weight — led to a spiral of health problems known as relative energy deficiency in sport, or RED-S syndrome. Also called the female athlete triad, the condition is triggered when athletes take in too few calories to support their training. Next, they stop having menstrual periods — and lose vital bone density as a result.

“I broke five different bones” because of RED-S, Cain says.

Cain says that after a disappointing finish in a race in 2015, Salazar yelled at her in front of a large crowd, saying he could tell she had gained 5 pounds.

“It was also that night that I told Alberto and our sports psych that I was cutting myself and they pretty much told me that they just wanted to go to bed,” Cain said. Soon afterward, she says she decided to leave Salazar’s program and return home to Bronxville, N.Y.

Salazar denies Cain’s accusations against him. NPR’s attempts to contact Salazar for comment so far have been unsuccessful. But The Oregonian quotes a statement from the famous coach in which he says, “To be clear, I never encouraged her, or worse yet, shamed her, to maintain an unhealthy weight.”

In that message, Salazar also says that Cain “struggled to find and maintain her ideal performance and training weight.” But he says he discussed the issue with Cain’s father, who is a doctor, and referred her to a female doctor, as well.

In response to Cain’s allegations, Nike says, “We take the allegations extremely seriously and will launch an immediate investigation to hear from former Oregon Project athletes.”

The company calls Cain’s claims “deeply troubling,” but it says that neither she nor her parents had previously raised the allegations.

“Mary was seeking to rejoin the Oregon Project and Alberto’s team as recently as April of this year and had not raised these concerns as part of that process,” a Nike spokesperson said in an email to NPR.

On Friday morning, Cain addressed her recent attempt to rejoin the team, saying via Twitter, “As recently as this summer, I still thought: ‘maybe if I rejoin the team, it’ll go back to how it was.’ But we all come to face our demons in some way. For me, that was seeing my old team this last spring.”

No more wanting them to like me. No more needing their approval. I could finally look at the facts, read others stories, and face: THIS SYSTEM WAS NOT OK. I stand before you today because I am strong enough, wise enough, and brave enough. Please stand with me.

— Mary Cain (@runmarycain) November 8, 2019

Over the summer, Cain says, she became convinced that Salazar only cared about her as “the product, the performer, the athlete,” not as a person. She adds that she decided to go public with her story after the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency punished Salazar earlier this year. Now Cain is calling for Nike to change its ways — and to ensure the culture that thrived under Salazar is eradicated.

“In track and field, Nike is all-powerful,” Cain says in the Times video. “They control the top coaches, athletes, races, even the governing body. You can’t just fire a coach and eliminate a program and pretend the problem is solved.”

She adds, “My worry is that Nike is merely going to rebrand the old program and put Alberto’s old assistant coaches in charge.”

The list of runners who have stepped forward to support Cain includes Canadian distance runner Cameron Levins, a former Olympian and NCAA champion who trained in the Oregon Project.

“I knew that our coaching staff was obsessed with your weight loss, emphasizing it as if it were the single thing standing in the way of great performances,” Levins said in a tweet directed at Cain.

“I knew because they spoke of it openly among other athletes,” he added.

Another athlete, former NCAA champion Amy Yoder Begley, said she was kicked out of the Oregon Project after she placed sixth in a 10,000-meter race in 2011.

After placing 6th in the 10,000m at the 2011 USATF championships, I was kicked out of the Oregon Project. I was told I was too fat and “had the biggest butt on the starting line.” This brings those painful memories back. https://t.co/ocIqnHDL8F

— Amy Yoder Begley OLY ???? (@yoderbegley) November 8, 2019

“I was told I was too fat and ‘had the biggest butt on the starting line,’ ” Begley said via Twitter. “This brings those painful memories back.”

Cain says her parents were “horrified” when she told them about her life in the Nike Oregon Project. “They bought me the first plane ride home,” she says. “They were like, ‘Get on that flight, get the hell out of there.’ “

On Friday, Cain thanked Levins for his support and said, “For so long, I thought I was the problem. To me, the silence of others meant that pushing my body past its healthy limits was the only way. But I know we were all scared, and fear keeps us silent.”

As for what changes Cain would like to see, she tells the Times that her sport needs more women in power.

“Part of me wonders if I had worked with more female psychologists, nutritionists and even coaches, where I’d be today,” Cain says. “I got caught in a system designed by and for men which destroys the bodies of young girls. Rather than force young girls to fend for themselves, we have to protect them.”

After being off the track-and-field radar for several years, Cain ran a 4-mile race on Mother’s Day in Central Park. In an interview earlier this year, she talked about what she would write in a letter to her younger self.

Here’s part of what Cain told Citius Mag:

“I think my letter would say, ‘Go have that milkshake. Go see that movie. Go out with that friend. Love running and commit to running but the best way to do that is to love yourself and commit to yourself. Make sure you’re doing those other things as well so that once you go out for a run, you’re so happy to be there.’ ”

High-Ranking Dog Provides Key Training For Military’s Medical Students

Service dogs can be trained to provide very different types of support to their human companions, as medical students learn from interacting with “Shetland,” a highly skilled retriever-mix.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

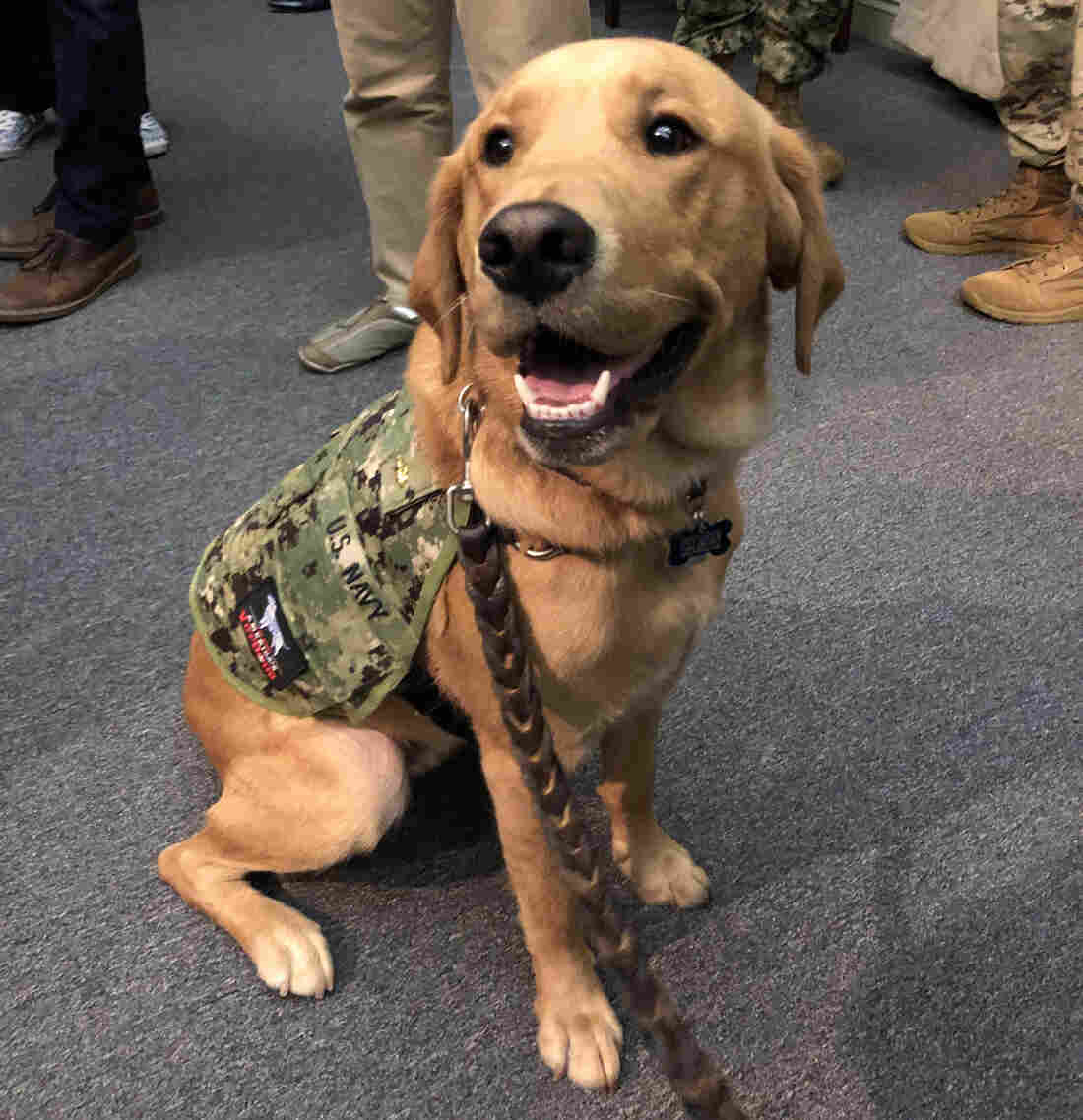

The newest faculty member at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences has a great smile ? and likes to be scratched behind the ears.

Shetland, not quite 2 years old, is half-golden retriever, half-Labrador retriever. As of this fall, he is also a lieutenant commander in the Navy and a clinical instructor in the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology at USUHS in Bethesda, Md.

Among Shetland’s skills are “hugging” on command, picking up a fallen object as small as a cellphone and carrying around a small basket filled with candy for harried medical and graduate students who study at the military’s medical school campus.

But Shetland’s job is to provide much more than smiles and a head to pat.

“He is here to teach, not just to lift people’s spirits and provide a little stress relief after exams,” says USUHS Dean Arthur Kellermann. He says students interacting with Shetland are learning “the value of animal-assisted therapy.”

The use of dogs trained to help their human partners with specific tasks of daily life has ballooned since studies in the 1980s and 1990s started to show how animals can benefit human health.

But helper dogs come in many varieties. Service dogs, like guide dogs for the blind, help people with disabilities live more independently. Therapy dogs can be household pets who visit people in hospitals, schools and nursing homes. And then there are highly trained working dogs, like the Belgian Malinois, that recently helped commandos find the Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Shetland is technically a “military facility dog,” trained to provide physical and mental assistance to patients as well as interact with a wide variety of other people.

His military commission does not entitle him to salutes from his human counterparts.

“The ranks are a way of honoring the services [of the dogs] as well as strengthening the bond between the staff, patients and dogs here,” says Mary Constantino, deputy public affairs officer at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. “Our facilities dogs do not wear medals, but do wear rank insignia as well as unit patches.”

USUHS, which trains doctors, dentists, nurses and other health professionals for the military, is on the same campus in suburban Washington, D.C. Two of the seven Walter Reed facility dogs ? Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Sully (the former service dog for President George H.W. Bush) and Marine Sgt. Dillon ? attended Shetland’s formal commissioning ceremony in September as guests.

The Walter Reed dogs, on campus since 2007, earn commissions in the Army, Navy, Air Force or Marines. They wear special vests designating their service and rank. The dogs visit and interact with patients in several medical units, as well as in physical and occupational therapy, and help boost morale for patients’ family members.

But Shetland’s role is very different, says retired Col. Lisa Moores, USUHS associate dean for assessment and professional development.

“Our students are going to work with therapy dogs in their careers and they need to understand what [the dogs] can do and what they can’t do,” she says.

As in civilian life, the military has made significant use of animal-assisted therapy. “When you walk through pretty much any military treatment facility, you see therapy dogs walking around in clinics, in the hospitals, even in the ICUs,” says Moores. Dogs also play a key role in helping service members who have post-traumatic stress disorder.

Students need to learn who “the right patient is for a dog, or some other therapy animal,” she says. “And by having Shetland here, we can incorporate that into the curriculum, so it’s another tool the students know they have for their patients someday.”

The students, not surprisingly, are thrilled by their newest teacher.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, says the Walter Reed dogs used to visit the school’s 1,500 students and faculty fairly regularly, but “having Shetland here all the time is optimal.” Wyatt says the only thing she knew about service dogs before — or at least thought she knew — was that “you’re not supposed to pet them.” But Shetland acts as both a service dog and a therapy dog, so can be petted, Wyatt learned.

Brelahn Wyatt, a Navy ensign and second-year medical student, shares a hug with Shetland. The dog’s military commission does not entitle him to salutes.

Julie Rovner/KHN

hide caption

toggle caption

Julie Rovner/KHN

Having Shetland around helps the students see “there’s a difference,” Wyatt says, and understand how that difference plays out in a health care setting. Like his colleagues Sully and Dillon, Shetland was bred and trained by America’s VetDogs.

The New York nonprofit provides dogs for “stress control” for active-duty military missions overseas, as well as service dogs for disabled veterans and civilian first responders.

Many of the puppies are raised by a team made up of prison inmates (during the week) and families (on the weekends), before returning to New York for formal service dog training. National Hockey League teams such as the Washington Capitals and New York Islanders also raise puppies for the organization.

Dogs can be particularly helpful in treating service members, says Valerie Cramer, manager of America’s VetDogs service dog program. “The military is thinking about resiliency. They’re thinking about well-being, about decompression in the combat zone.”

Often people in pain won’t talk to another person but will open up in front of a dog. “It’s an opportunity to start a conversation as a behavioral health specialist,” Cramer says.

While service dogs teamed with individuals have been trained to perform both physical tasks and emotional ones — such as gently waking a veteran who is having a nightmare — facility dogs like Shetland are special, Cramer says.

“That dog has to work in all different environments with people who are under pressure. It can work for multiple handlers. It can go and visit people; can go visit hospital patients; can knock over bowling pins to entertain, or spend time in bed with a child.”

The military rank the dogs are awarded is no joke. They can be promoted ? as Dillon was from Army specialist to sergeant in 2018 ? or demoted for bad behavior.

“So far,” Kellermann says, “Shetland has a perfect conduct record.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit, editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.