Former Arkansas VA Doctor Charged With Involuntary Manslaughter In 3 Deaths

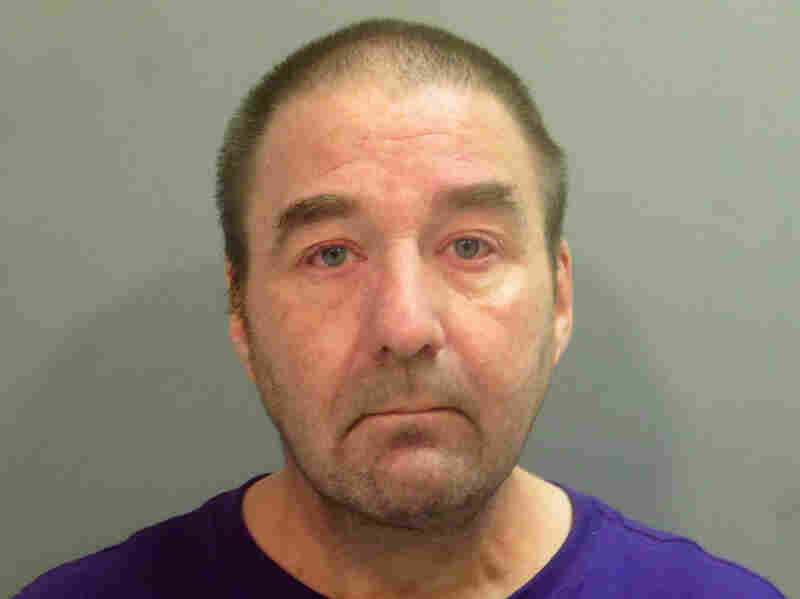

Pathologist Robert Levy was fired from an Arkansas veterans hospital after officials said he had been impaired while on duty.

AP

hide caption

toggle caption

AP

A former pathologist at an Arkansas veterans hospital was charged with three counts of involuntary manslaughter in the deaths of three patients whose records he allegedly falsified to conceal his misdiagnoses.

According to federal prosecutors, Dr. Robert Morris Levy, 53, is also charged with four counts of making false statements, 12 counts of wire fraud and 12 counts of mail fraud, stemming from his efforts to conceal his substance abuse while working at the Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks.

Levy was suspended from work twice — in March 2016 and again in October 2017 — for working while impaired, before he was fired in April 2018.

A June 2018 review of his work examined 33,902 cases and found more than 3,000 mistakes or misdiagnoses of patients at the veterans hospital dating to 2005. Thirty misdiagnoses were found to have resulted in serious health risks to patients.

The three deaths came as a result of incorrect or misleading diagnoses. In one case, according to prosecutors, a patient died of prostate cancer after Levy concluded that a biopsy indicated that he didn’t have cancer.

“This indictment should remind us all that this country has a responsibility to care for those who have served us honorably,” Duane Kees, the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Arkansas, said in a statement. “When that trust is violated through criminal conduct, those responsible must be held accountable. Our veterans deserve nothing less.”

Kees said Levy went to great lengths to conceal his substance abuse even during a period when he had pledged to maintain his sobriety.

Levy used 2-Methyl-2-butanol, a chemical substance that intoxicates a person “but is not detectable in routine drug and alcohol testing methodology,” the statement said.

Ex-MLB Players Luis Castillo, Octavio Dotel Linked To Alleged Dominican Drug Lord

Octavio Dotel, then a pitcher for the Kansas City Royals, seen during a 2007 game. Dominican Republic authorities arrested the former MLB player, saying both he and ex-infielder Luis Castillo were linked with an alleged drug trafficker.

Charlie Riedel/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Charlie Riedel/AP

Two former Major League Baseball stars, pitcher Octavio Dotel and infielder Luis Castillo, have been implicated in a massive drug trafficking bust in the Dominican Republic. The country’s attorney general, Jean Alain Rodríguez, announced Tuesday that the operation targeted alleged drug kingpin César Emilio Peralta, also known as “César the abuser,” and the extensive criminal operation he led.

Castillo is not the current Cincinnati Reds player of the same name. The Luis Castillo accused by authorities played with the then-Florida Marlins and the New York Mets.

Hundreds of narcotics agents, prosecutors and other government officials took part in the attempt to dismantle Peralta’s network, which Rodríguez called “the most important drug trafficking structure in the region” and that also included alleged money laundering. Dotel is among the suspects arrested, and Rodríguez named Castillo as one of the 18 figures linked to Peralta — though both Castillo and Peralta remained at large at the time of the attorney general’s announcement.

Rodríguez did not immediately specify the role authorities believe the two former baseball players performed in Peralta’s operation. He said his team had collaborated with the U.S. during the investigation, exchanging information with the FBI and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury got involved Tuesday as well, sanctioning Peralta and his organization as “significant narcotics traffickers.”

“César Emilio Peralta and his criminal organization have used violence and corruption in the Dominican Republic to traffic tons of cocaine and opioids into the United States and Europe,” Sigal Mandelker, the undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, said in a statement released by the department. “Treasury is targeting these Dominican drug kingpins, their front persons, and the nightclubs they have used to launder money and traffic women.”

“Only God knows the truth,” Castillo said on Instagram after Rodríguez’s news conference.

During his playing career Castillo was a three-time All-Star, three-time Golden Glove winner and World Series winner as part of the 2003 Florida Marlins. Dotel, for his part, is one of the all-time MLB leaders in the number of franchises played for: 13 teams during his 14-year career.