Can Fast Fashion And Sustainability Be Stitched Together?

Zara’s parent company Inditex announced new sustainability goals this month. But can a fast-fashion brand built on growth truly become sustainable?

Marcos del Mazo/LightRocket via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Marcos del Mazo/LightRocket via Getty Images

As a fashion brand, Zara has made a name for itself by democratizing the latest clothing styles for consumers at an affordable price. But the rapid pace of that trend-driven business model, known as “fast fashion,” can come at high environmental and social costs.

Last week, Zara’s parent company, Inditex, announced its plans to grow more sustainable.

The fast-fashion giant pledged that by 2025, all of its eight brands will only use cotton, linen and polyester that’s organic, sustainable or recycled, which is 90% of the raw materials its uses. CEO and executive chairman Pablo Isla said that renewable sources will power 80% of the energy consumed by the conglomerate’s distribution centers, offices and stores. It also plans to transition to zero landfill waste.

It’s a significant step for a company that churns out 500 new designs per week, says Elizabeth L. Cline, the author of two books on the impact of fast fashion.

“What they’re doing is they’re sourcing materials that do have a better environmental profile,” she says. “These are materials that use less water, less energy, less chemicals to produce.”

Cline says the move sends a powerful message down the supply chain to manufacturers about being more green.

Still, Cline cautions that the announcement should be taken with a grain of salt, arguing that fast fashion and sustainability are inherently incompatible.

Cline says that even if Zara is using materials that are more ethically sourced or have a lower environmental impact, the vast majority of the carbon footprint of fashion comes from the manufacturers who supply brands with their materials. When a business is built on a fast turnover of styles, making those products still swallows a lot of energy, regardless of whether it’s using organic cotton or selling products in more eco-efficient stores.

“The business model will have to change and evolve for them to operate sustainably,” she says.

Agriculturally, growing cotton impacts soil health, carbon emissions and water consumption, says Mark Sumner, who lectures on fashion and sustainability at the University of Leeds in England. Polyester, a popular and cheap synthetic material in fast fashion, requires the oil industry’s extraction and refinement of petroleum, processes known to fuel climate change. Then there’s the energy-intensive processes of converting that raw material into wearable garments. Dying the fabric can also introduce harmful chemicals.

“When we add up all of those different impacts we then start to get to see a picture of those environmental issues associated with clothing,” he says.

What complicates things even more, says Sumner, is that depending on who you ask, the definition of sustainability can vary.

“The fashion industry isn’t actually just one industry, it’s a whole raft of other industries that are used and exploited to deliver the garments that we’re wearing now,” he says in an interview with NPR’s All Things Considered.

Which is why Cline thinks any excitement over Inditex’s announcement needs to be tempered.

“They’re acting overly confident about a subject that we’re still figuring out,” she says. “We are still gathering data. We are still figuring out best practices. So for Zara to kind of come out of the gate and say we’re going to be sustainable by 2025 belies the long road ahead of us that we have on sustainability and fashion.”

Inditex is committing $3.5 million to researching textile recycling technology under a partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, an investment Cline supports.

At the same time, Cline says it can’t be up to the fast-fashion industry alone. Consumers and government regulators have a role to play too.

Inditex’s announcement is a response to consumer pressure, Cline says. “We’re in the midst of a consumer-led revolution in fashion sustainability.”

Unfortunately, she says, a big part of that movement is tilted toward greenwashing — a term that refers to a deceptive marketing ploy in which companies spend more effort on its eco-consciousness image than actually being eco-conscious.

The fact that Zara’s parent company has gone public with its sustainability targets is a good sign, Sumner says.

“Over time, they’ll be held accountable by their shareholders, by NGOs, by media by commentators,” he says. “Hopefully, what they will do is also encourage other brands and retailers to be bold and to make these statements as well.”

NPR’s Leena Sanzgiri and Tinbete Ermyas produced and edited the audio of this story.

Sports Roundup: Boxing Deaths, Olympic Swimming And The WNBA

Two boxing deaths in one week, a preview of Olympic swimming, and a check-in about the WNBA: Host Scott Simon gets an update from NPR sports correspondent Tom Goldman.

SCOTT SIMON, HOST:

And now it’s time for sports.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

SIMON: Swim records fall in Korea. The WNBA season reaches its halfway mark with today’s All-Star Game. And twin tragedies in the grisly business of boxing. NPR’s Tom Goldman joins us. Tom, thanks for being with us.

TOM GOLDMAN, BYLINE: Thank you, Scott.

SIMON: Not one, even, but two boxing deaths this week.

GOLDMAN: Yeah. Russian Maxim Dadashev and Argentine Hugo Santillan both died from brain injuries a few days after their fights last weekend. Certainly not the first boxing deaths, but being so close together – just two days apart – that’s very dramatic and has the boxing world split once again between those calling for reform and those saying, it’s tragic, but it’s just part of the game.

SIMON: You and I have both reported on the human damage in boxing over the years, and I daresay it’s one of the reasons we don’t talk about it a lot here. We – you know, we both recoil at this sometimes really being called a sport, and you and I love sports. We often talk about what boxing should do. Is there something fans can do to make it less destructive?

GOLDMAN: You know, I suppose they can take their money out of the sport. As long as there’s demand, boxing will continue and not see a need to change. But if fans stop betting, if they stop buying pay-per-view, stop attending fights and let the powers that be know this is a protest, maybe that would spur the kind of reform that might help reducing the length of fights, zero tolerance of performance-enhancing drugs, which there isn’t now, ringside doctors with neurological and concussion training at all fights and ensuring boxers train safely. Brain injuries may happen initially in training and not be detected by the time they fight.

But, you know, Scott, even if meaningful reform happens, death happens too. You know, it’s the nature of a sport where the goal is to hit someone to the point of unconsciousness. And in the words of Hall of Fame boxing writer Nigel Collins, it’s up to each of us to face that reality and decide whether or not it’s worth the price.

SIMON: Yeah. Las Vegas this afternoon, the WNBA All-Star Game means the women’s basketball season’s halfway through. What teams have been most successful so far?

GOLDMAN: Well, it’s been a very competitive season so far, led by Connecticut and Las Vegas, both with 13 and six records, but not leading by much. Eight of the 12 WNBA teams go to the playoffs. And the eighth team, Minnesota, is only three and a half games out of first place. The contenders include defending champion Seattle, which lost league most valuable player Breanna Stewart and star Sue Bird before the season to injuries. There were predictions of doom, but the Storm have stayed together. They’ve played well, and they’re in the thick of the race right now.

SIMON: And, Tom, we’re a year out from the 2020 Olympics.

GOLDMAN: Yeah.

SIMON: The World Swimming Championships are – I know you’ve just begun to pack – World Swimming Championships are taking place in South Korea right now. What might we see in these championships that can help us look forward to next year in Tokyo?

GOLDMAN: Well, you know, it might be a good preview, although Americans hope not too much of a preview for super swimmer Katie Ledecky. She’s had a really tough time of it in South Korea. Illness forced her to drop out of two events. But just today, Scott…

SIMON: Yeah.

GOLDMAN: …Some redemption.

SIMON: I saw.

GOLDMAN: Yeah, she won the 800-meter freestyle for the fourth straight time, a four-peat, at the World Championships. And for those who love controversy, there’s been plenty of that related to China’s Sun Yang. There are strong doping suspicions about him. He served a drug ban five years ago. And fellow swimmers haven’t been shy about speaking or acting out.

Competitors who won medals in races he won refused to stand on the victory stand with him. And after he won the 200-meter freestyle, British swimmer Duncan Scott, who tied for third, wouldn’t have his picture taken with Sun as they left the stage. Sun turned around and called Scott a loser and said he, Sun, was a winner. Now, Scott, whether this all plays out at the Olympics depends on an upcoming hearing where Sun could get a lifetime…

SIMON: That – I mean, this is, like, really dramatic. Who wouldn’t watch this?

GOLDMAN: (Laughter) Well, he could get a lifetime ban, though, for a strange incident with drug testers who showed up to give him a drug test, but he reportedly destroyed blood samples with a hammer…

SIMON: Yeah.

GOLDMAN: …That he’d given to those testers. So we’ll see if that plays out in Tokyo.

SIMON: Well, that gets the job done. NPR’s Tom Goldman. Thanks.

GOLDMAN: (Laughter).

SIMON: What do you think we do with – they do with our interviews? NPR’s Tom Goldman, thanks so much.

GOLDMAN: (Laughter) You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Genetic Counselors Of Color Tackle Racial, Ethnic Disparities In Health Care

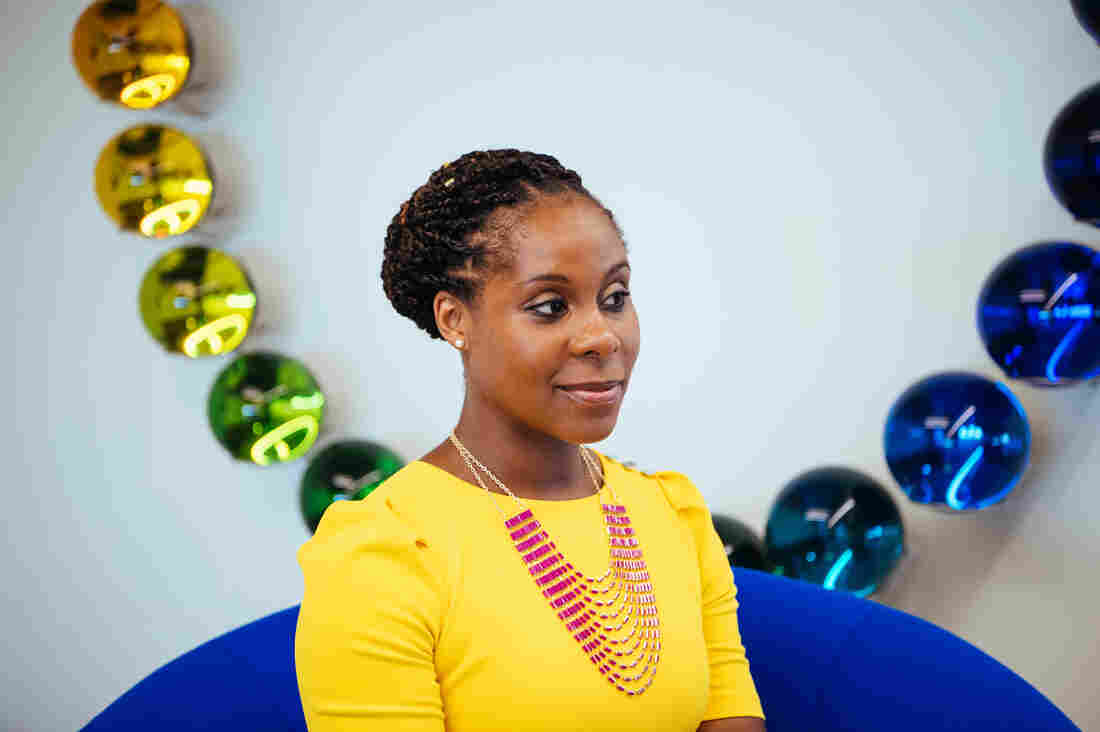

Altovise Ewing, who has a doctorate in human genetics and counseling, now works as a genetic counselor and researcher at 23andMe, one of the largest direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies, based in Mountain View, Calif.

Karen Santos for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Santos for NPR

Altovise Ewing was a senior at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tenn., when she first learned what a genetic counselor was. Although she had a strong interest in research, she suspected working in a lab wasn’t for her — not enough social interaction.

Then, when a genetic counselor came to her class as a guest lecturer, Ewing had what she recalls as a “lightbulb moment.” Genetic counseling, she realized, would allow her to be immersed in the science but also interact with patients. And maybe, she thought, she’d be able to help address racial health disparities, too.

That was 15 years ago. Ewing, who went on to earn a doctorate in Genetics and Human Genetics/Genetic Counseling from Howard University, now works as a genetic counselor for 23andMe, one of the largest direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies. As a black woman, Ewing is also a rarity in her profession.

Genetic counselors work with patients to decide when genetic testing is appropriate, interpret any test results and counsel patients on the ways hereditary diseases might impact them or their families. According to data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of genetic counselors is expected to grow by 29% between 2016 and 2026, compared with 7% average growth rate for all occupations.

23andMe’s Ewing says the lack of ethnic diversity among genetic counselors in the U.S. reduces some people’s willingness to participate in clinical trials, “because they’re not able to connect with the counselor or the scientist involved in the research initiative.”

Karen Santos for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Karen Santos for NPR

However, despite the field’s rapid growth, the number of African Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans working as genetic counselors has remained low.

As genetics’ role in medicine expands, diversity among providers is crucial, say people working in the field. “It is well documented that people want medical services from people who look like them, and genetic counseling is not an exception,” says Barbara Harrison, an assistant professor and genetic counselor at Howard University.

Ana Sarmiento, who wrote her master’s thesis on the importance of diversity among genetic counselors, has seen this firsthand.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen the look of relief on a Spanish-speaking patient’s face when they realize they can communicate with me,” says Sarmiento, a recent graduate of Brandeis University’s genetic counseling program. “It’s what keeps me passionate about being a genetic counselor.”

Ethnic and gender diversity among providers can also increase the depth and scope of information patients are willing to share in the clinical settings — information that’s important to their health.

“In my opinion,” says Erica Price, who just received her master’s in genetic counseling from Arcadia University, “no one fights for the black community the way other black people do. I encounter a lot of other African Americans who don’t know what genetic counseling is. But when they find out that I’m a genetic counselor, they will give me their entire family medical history.”

Bryana Rivers, who is African American, recently graduated from the University of Cincinnati’s genetic counseling program, and wrote last year about her experience with a black mother whose two children had undergone extensive genetic testing to try to determine the cause of their developmental delays.

Having a firm diagnosis, the mother explained to Rivers, could help the children get access to the resources they needed in school. The mom wanted to know if the genetic variant that had been identified in her children — one that geneticists had decided was a “variant of unknown significance” — had been observed in other black families.

That question, which she hadn’t brought up in earlier discussions with health providers who weren’t African American, led to a broader, candid discussion of what these unknown variants mean and don’t mean, and why they are more common among members of understudied minorities.

“I cannot stress enough how important it is for patients to feel comfortable, to feel heard, and to know that they will not be ignored or discriminated against by their providers based on the color of their skin,” Rivers wrote in her blog post.

“I don’t want to suggest that a genetic counselor who wasn’t black wouldn’t have listened to her, but there are factors outside of what we do and say that can have an impact on our patients. Just the fact that she was able to lower her guard a bit because we share the same racial background as her speaks volumes.”

In an interview Rivers also recounted a recent session conducted by a white female genetic counselor that Rivers was shadowing that day. The patient, who was a black woman, addressed all of her answers to Rivers, although Rivers’ official role was to merely observe the appointment.

“I do feel a responsibility as a black provider to look out for my black patients and make sure they are receiving the appropriate care,” Rivers says. “Not everyone is willing to go that extra mile, and they may be more dismissive of the concerns of black patients and may not actually hear them.”

Ewing, who also conducts research, adds that the lack of diversity among genetic counselors has had a negative impact on research.

“The lack of diversity has an effect on the willingness of minorities to pursue clinical trials, because they’re not able to connect with the counselor or the scientist involved in the research initiative,” she explains. “We are now in the era of precision and personalized medicine and we need people who are comfortable talking about genetic and genomic information with people from all walks of life, so that we’re reaching all demographics.”

Since 1992, the National Society of Genetic Counselors, the largest professional organization for genetic counselors in the United States, has conducted an annual survey on the demographics of its members. Between 1992 and 2006, non-Hispanic white genetic counselors made up 91 to 94.2% of the NSGC’s membership.

In 2019, 90% of survey respondents identified as Caucasian, while only 1% of respondents identified as Black or African-American. Just over 2% of respondents identified as Hispanic, 0.4% identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native.

Some genetic counselors cite a lack of awareness among underrepresented minorities of genetic counseling as a profession as a major barrier to diversity in the field. Rivers says she had little exposure to genetic counseling as a future career path while enrolled as a biology major at the University of Maryland.

“My university stressed medical school, nursing school, or a Ph.D. in the biological sciences,” Rivers recalls. “I only had one professor in four years bring up genetic counseling.”

Samiento concurs. “You don’t have 6-year-olds running around saying ‘I want to be a genetic counselor’ — because it’s not a high visibility profession,” she says. “There are also very few minority professionals in the training programs and it takes a brave minority to look at the sea of white female faces and say ‘yes I can fit in here.’ “

“Genetic counseling is still a relatively new profession and there hasn’t been enough time and exposure for people to view [the field] the way they view other medical professions,” says Price. “People have asked me why I would pursue genetic counseling when I could be a physician assistant or a nurse or go to medical school.”

After Price’s acceptance to graduate school, one of her undergraduate professors questioned her chosen career path. “She said to me, ‘You’re a black woman in the sciences. We could have gotten you into a Ph.D. program or something where you’re making more money.’ “

As a part of its strategic plan for the years 2019-2021, the NSGC has identified diversity and inclusion as one of its four areas of strategic focus. Specific plans include developing mechanisms to highlight genetic counseling as a career in hard-to-reach communities by the end of the year. Erica Ramos, who is the immediate past president of the NSGC and serves as the board liaison to the task force, says she is optimistic that the numbers of underrepresented minorities in the field will improve.

“People in the profession have realized that we have blinders on,” she says. “But as an organization, the NSGC has been asking questions about how we can improve on diversity and be supportive of existing minority genetic counselors. We had 100 people apply to serve on the task force.”

A number of genetic counselors from diverse backgrounds have also come together to form their own support and advocacy networks. In November 2018, the Minority Genetic Professionals Network was formed to provide a forum for genetic counselors from diverse backgrounds to connect with one another.

Erika Stallings is an attorney and freelance writer based in New York City. Her work focuses on health care disparities, with a focus on breast cancer and genetics. Find her on Twitter: @quidditch424.