Pain Meds As Public Nuisance? Oklahoma Tests A Legal Strategy For Opioid Addiction

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter begins closing statements during the opioid trial at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla., on Monday, July 15. It’s the first public trial to emerge from roughly 2,000 U.S. lawsuits aimed at holding drugmakers accountable for the nation’s opioid epidemic.

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

A global megacorporation best known for Band-Aids and baby powder may have to pay billions for its alleged role in the opioid crisis. Johnson & Johnson was the sole defendant in a closely-watched trial that wrapped up in Oklahoma state court this week, with a decision expected later this summer. The ruling in the civil case could be the first that would hold a pharmaceutical company responsible for one of the worst drug epidemics in American history.

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter‘s lawsuit alleges Johnson & Johnson and its subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals helped ignite the opioid crisis with overly aggressive marketing, leading to thousands of overdose deaths over the past decade in Oklahoma alone.

The trial took place over seven weeks in the college town of Norman. Instead of a jury, a state judge heard the case.

During closing arguments Monday, Hunter called the company the “kingpin” of the opioid crisis.

“What is truly unprecedented here is the conduct of these defendants on embarking on a cunning, cynical and deceitful scheme to create the need for opioids,” Hunter said.

The state urged Judge Thad Balkman, who presided over the civil trial for seven weeks, to find Johnson & Johnson liable for creating a “public nuisance” and force the company to pay more than $17 billion over 30 years to abate the public health crisis in the state.

Driving the opioid crisis home has been a cornerstone of the Oklahoma’s lawsuit. In closing arguments Monday, one of the state’s attorneys, Brad Beckworth, cited staggering prescribing statistics in Cleveland County, where the trial took place.

“What we do have in Cleveland County is 135 prescription opioids for every adult,” Beckworth explained. “Those didn’t get here from drug cartels. They got here from one cartel: the pharmaceutical industry cartel. And the kingpin of it all is Johnson & Johnson.”

Johnson & Johnson’s attorney Larry Ottaway, rejected that idea in his closing argument, saying the company’s products, which had included the fentanyl patch Duragesic and the opioid-based pill Nucynta, were minimally used in Oklahoma.

He scoffed at the idea that physicians in the state were convinced to unnecessarily prescribe opioids due to the company’s marketing tactics.

“The FDA label clearly set forth the risk of addiction, abuse and misuse that could lead to overdose and death. Don’t tell me that doctors weren’t aware of the risks,” Ottaway said.

Defense attorney Larry Ottaway speaks for Johnson & Johnson during closing arguments. Oklahoma is asking a state judge for $17.5 billion to help pay for addiction treatment and prevention.

Sue Ogrocki/AP Photo

hide caption

toggle caption

Sue Ogrocki/AP Photo

Ottaway played video testimony from earlier in the trial, showing Oklahoma doctors who said they were not misled about the drugs’ risks before prescribing them.

“Only a company that believes its innocence would come in and defend itself against a state, but we take the challenge on because we believe we are right,” Ottaway said in his closing argument.

Johnson & Johnson fought on after settlements

Initially, Hunter’s lawsuit included Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin. In March, Purdue Pharma settled with the state for $270 million. Soon after, Hunter dropped all but one of the civil claims, including fraud, against the two remaining defendants.

Just two days before the trial began, another defendant, Teva Pharmaceuticals of Jerusalem, announced an $85 million settlement with the state. The money will be used for litigation costs and an undisclosed amount will be allocated “to abate the opioid crisis in Oklahoma,” according to a press release from Hunter’s office.

Both companies deny any wrongdoing.

The legal liability of ‘public nuisance’

Most states and more than 1,600 local and tribal governments are suing drugmakers who manufactured various kinds of opioid medications, and drug distributors. They are trying to recoup billions of dollars spent addressing the human costs of opioid addiction.

“Everyone is looking to see what’s going to happen with this case, whether it is going to be tobacco all over again, or whether it’s going to go the way the litigation against the gun-makers went,” says University of Georgia law professor Elizabeth Burch.

But the legal strategy is complicated. Unlike the tobacco industry, from which states won a landmark settlement, the makers of prescription opioids manufacture a product that serves a legitimate medical purpose, and is prescribed by highly trained physicians — a point that Johnson & Johnson’s lawyers made numerous times during the trial.

Oklahoma’s legal team based its entire case on a claim of public nuisance, which refers to actions that harm members of the public, including injury to public health. Burch says each state has its own public nuisance statute, and Oklahoma’s is very broad.

“Johnson & Johnson, in some ways, is right to raise the question: If we’re going to apply public nuisance to us, under these circumstances, what are the limits?” Burch says. “If the judge or an appellate court sides with the state, they are going to have to write a very specific ruling on why public nuisance applies to this case.”

Burch says the challenge for Oklahoma has been to tie one opioid manufacturer to all of the harms caused by the ongoing public health crisis, which includes people struggling with addiction to prescription drugs, but also those harmed by illegal street opioids, such as heroin.

University of Kentucky law professor Richard Ausness agrees that it’s difficult to pin all the problems on just one company.

“Companies do unethical or immoral things all the time, but that doesn’t make it illegal,” Ausness says.

Judge Thad Balkman listens to closing statements at the Cleveland County Courthouse. The case was a bench trial, with both sides seeking to persuade a single judge instead of a jury. Balkman is expected to issue his decision in August.

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Landsberger/The Oklahoman

If the judge rules against Johnson & Johnson, Ausness says, it could compel other drug companies facing litigation to settle out of court. Conversely, a victory for the drug giant could embolden the industry in the other cases.

Earlier in the trial, the state’s expert witness, Dr. Andrew Kolodny, testified that Johnson & Johnson did more than push its own pills — until 2016, it also profited by manufacturing raw ingredients for opioids and then selling them to other companies, including Purdue, which makes Oxycontin.

“Purdue Pharma and the Sacklers have been stealing the spotlight, but Johnson & Johnson in some ways, has been even worse,” Kolodny testified.

Kolodny says that’s why the company downplayed to doctors the risks of opioids as a general class of drugs, knowing that almost any opioid prescription would benefit its bottom line.

The state’s case also focused on the role of drug sales representatives. Drue Diesselhorst was one of Johnson & Johnson’s busiest drug reps in Oklahoma. Records discussed during the trial showed she continued to call on Oklahoma doctors who had been disciplined by the state for overprescribing opioids. She even continued to meet with doctors who had patients who died from overdoses.

But Diesselhorst testified she didn’t know about the deaths, and no one ever instructed her to stop targeting those high-prescribing physicians.

“My job was to be a sales rep. My job was not to figure out the red flags,” she said on the witness stand.

The role and responsibility of doctors

Throughout the trial, Johnson & Johnson’s defense team avoided many of the broader accusations made by the state, instead focusing on the question of whether the specific opioids manufactured by the company could have caused Oklahoma’s high rates of addiction and deaths from overdose.

Johnson & Johnson’s lawyer, Larry Ottaway, argued the company’s opioid products had a smaller market share in the state compared to other pharmaceutical companies, and he stressed that the company made every effort when the drugs were tested to prevent abuse. He also pointed out that the sale of both the raw ingredients and prescription opioids themselves are heavily regulated.

“This is not a free market,” he said. “The supply is regulated by the government.”

Ottaway maintained the company was addressing the desperate medical need of people suffering from debilitating, chronic pain — using medicines regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Even Oklahoma purchases these drugs, for use in state health care services.

Next steps

Judge Thad Balkman is expected to announce a verdict in August.

If the state’s claim prevails, Johnson & Johnson could, ultimately, have to spend billions of dollars in Oklahoma helping to ease the epidemic. State attorneys are asking that the company pay $17.5 billion over 30 years, to help abate” the crisis in the state.

Balkman could choose to award the full amount, or just some portion of it, if he agrees with the state’s claim.

“You know, in some ways I think it’s the right strategy to go for the $17 billion,” Burch says. “[The state is saying] look, the statute doesn’t limit it for us, so we’re going to ask for everything we possibly can.”

In the case of a loss, Johnson & Johnson is widely expected to appeal the verdict. If Oklahoma loses, the state will appeal, Attorney General Mike Hunter said Monday.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with StateImpact Oklahoma and Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Google’s Search Bias On Trial In Washington

A Senate subcommittee is looking to see if Google is keeping conservative media and bloggers out of top search results.

Alastair Pike /AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Alastair Pike /AFP/Getty Images

Updated at 5:15 p.m. ET

Does Google have bias?

It’s the question that’s at the center of a hearing Tuesday by a Senate Judiciary subcommittee.

The hearing is probing into Google’s search engine and whether it censors conservative media and bloggers out of the top search results.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, the subcommittee chairman, called the hearing after Google failed to attend an April hearing on the topic. Facebook and Google attended.

Cruz said he’s concerned about Google’s control over what people see on the Internet, and said previous legislation passed to protect tech companies was not created to “empower large technology companies to control our speech.”

“When you submit a video, people at YouTube determine whether you’ve engaged in hate speech, an ever-changing and vague standard meant to give censorship an air of legitimacy,” Cruz said. “This is a staggering amount of power to ban speech, to manipulate search results, to destroy rivals and to shape culture.”

President Trump has alleged that big tech companies have an anti-conservative bias. On Dec. 18, 2018, the president tweeted: “Facebook, Twitter and Google are so biased toward the Dems it is ridiculous!”

Facebook, Twitter and Google are so biased toward the Dems it is ridiculous! Twitter, in fact, has made it much more difficult for people to join @realDonaldTrump. They have removed many names & greatly slowed the level and speed of increase. They have acknowledged-done NOTHING!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 18, 2018

Google has denied the claim.

“Google needs to be useful for everyone, regardless of race, nationality or political leanings,” Google’s Vice President for Government Affairs and Public Policy Karan Bhatia said at Tuesday’s hearing. “We have a strong business incentive to prevent anyone from interfering with the integrity of our products, or the results we provide to our users. Our platform reflects the online world that exists.”

Johnny Clegg, A Uniting Voice Against Apartheid, Dies At 66

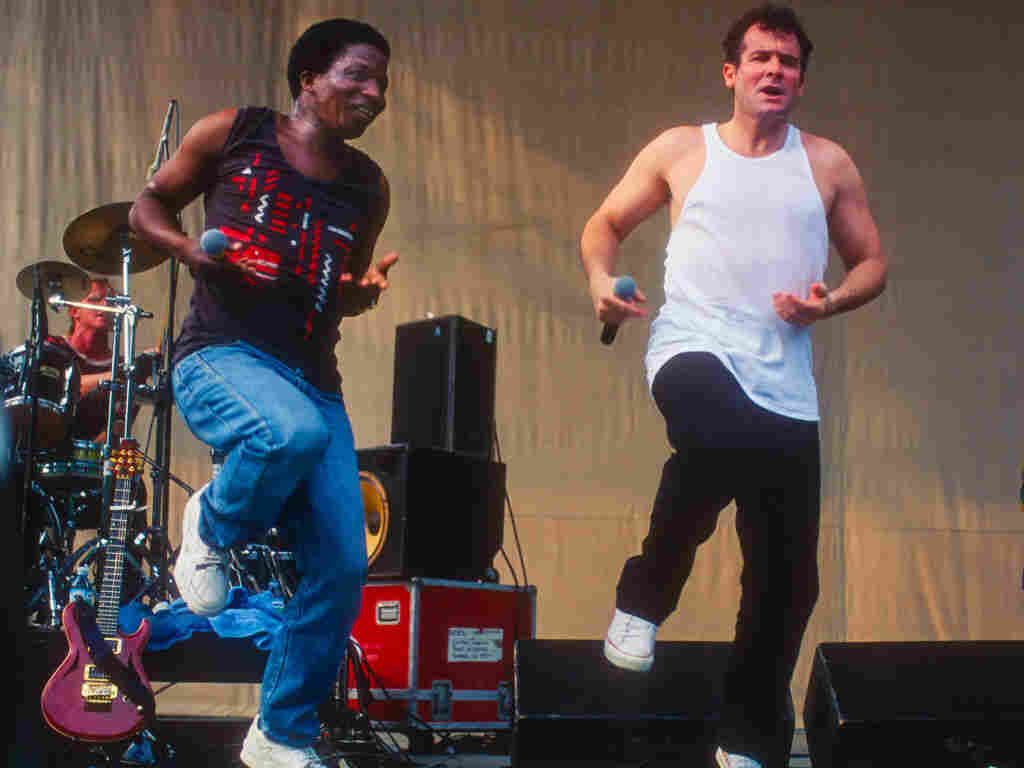

South African musician Johnny Clegg, right, with his longtime bandmate Sipho Mchunu, performing in New York City in 1996. Clegg died Tuesday at age 66.

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

One of the most celebrated voices in modern South African music has died. Singer, dancer and activist Johnny Clegg, who co-founded two groundbreaking, racially mixed bands during the apartheid era, died Tuesday in Johannesburg at age 66. He had battled pancreatic cancer since 2015.

His death was announced by his manager and family spokesperson, Roddy Quin.

Clegg wrote his 1987 song “Asimbonanga” for Nelson Mandela. It became an anthem for South Africa’s freedom fighters.

Johnny Clegg was born in England, but he became one of South Africa’s most creative and outspoken cultural figures. He moved around a lot, as a white child born to an English man and a female jazz singer from Zimbabwe (then known as Southern Rhodesia). His parents split up while he was still a baby; Clegg’s mother took him to Zimbabwe before she married again, this time to a South African crime reporter, when he was 7. The family moved north to Zambia for a couple of years, and then settled in Johannesburg.

He discovered South Africa’s music when he was a young teenager in Johannesburg. He had been studying classical guitar, but chafed under its strictness and formality. When he started hearing Zulu-style guitar, he was enchanted — and liberated.

“I stumbled on Zulu street guitar music being performed by Zulu migrant workers, traditional tribesmen from the rural areas,” he told NPR in a 2017 interview. “They had taken a Western instrument that had been developed over six, seven hundred years, and reconceptualized the tuning. They changed the strings around, they developed new styles of picking, they only use the first five frets of the guitar — they developed a totally unique genre of guitar music, indigenous to South Africa. I found it quite emancipating.”

He soon found a local, black teacher — who took him into neighborhoods where whites weren’t supposed to go. He went to the migrant workers’ hostels: difficult, dangerous places where a thousand or two young men at a time struggled to survive. But on the weekends, they kicked back, entertaining each other with Zulu songs and dances.

Because Clegg was so young, he was accepted in their communities, and in those neighborhoods, he discovered his other great passion: Zulu dance, which he described as a kind of “warrior theater” with its martial-style movements of high kicks, ground stamps and pretend blows.

“The body was coded and wired — hard-wired — to carry messages about masculinity which were pretty powerful for a young, 16-year-old adolescent boy,” he observed. “They knew something about being a man, which they could communicate physically in the way that they danced and carried themselves. And I wanted to be able to do the same thing. I fell in love with it. Basically, I wanted to become a Zulu warrior. And in a very deep sense, it offered me an African identity.”

And even though he was white, he was welcomed into their ranks, despite the dangers to both him and his mentors. He was arrested multiple times for breaking the segregation laws.

“I got into trouble with the authorities, I was arrested for trespassing and for breaking the Group Areas Act,” he told NPR. “The police said, ‘You’re too young to charge. We’re taking you back to your parents.'”

He persuaded his mother to let him go back. And it was through his dance team that he met one of his longest musical collaborators: Sipho Mchunu. As a duo, they played traditional maskanda guitar music for about six or seven years.

“We couldn’t play in public,” Clegg remembered, “so we played in private venues, schools, churches, university private halls. We played a lot of embassies. We played a lot of consulates.”

Over time, they started thinking bigger; Clegg wanted to try to meld Zulu music with rock and with Celtic folk.

“I was exposed to Celtic folk music early on,” he told NPR. “I never knew my dad, and music was one way which I can connect with that country. I liked Irish, Scottish and English folk music. I had a lot of tapes and recordings of them. And my stepfather was a great fan of pipe music. On Sundays, he would play an LP of the Edinburgh Police Pipe Band.”

Clegg was sure that he heard connections between the rural music of South Africa’s Natal province (now known as KwaZulu-Natal) — the music that he was learning from his black friends and teachers — and the sounds of Britain. So Clegg and Mchunu founded a fusion band called Juluka — “Sweat” in Zulu.

At the time, Johnny was a professor of anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg; Sipho was working as a gardener. They dreamed of getting a record deal even though they knew they couldn’t get airplay, or perform publicly in South Africa.

It was a hard sell to labels. South African radio was strictly segregated, and record companies refused to believe that an album sung partly in Zulu and partly in English would find an audience in any case. Clegg told NPR that their songs’ primary subject material wasn’t setting off any sparks with record producers, either.

“You know, ‘Who really cares about cattle? You’re singing about cattle. You know we’re in Johannesburg, dude, get your subject matter right!’ Clegg recalled. “But I was shaped by cattle culture, because all the songs I learned were about cattle, and I was interested. I was saying, ‘There’s a hidden world. And I’d like to put it on the table.'”

They got a record deal with producer Hilton Rosenthal, who released Juluka’s debut album, Universal Men, on his own label, Rhythm Safari, in 1979. And the band managed to find an audience both at home and abroad. One of its songs, “Scatterlings of Africa,” became a chart hit in the U.K.

YouTube

The band toured internationally for several years, and went. But eventually, Mchunu decided he’d had enough. He wanted to go home — not just to Johannesburg, but home to his native region of Zululand, in the KwaZulu-Natal province, to raise cattle.

“It was really hard for Sipho,” Clegg told NPR. “He was a traditional tribesman. To be in New York City, he couldn’t speak English that well — there were times when I think he felt he was on Mars. And after some grueling tours, he said to me, ‘I gave myself 15 years to make it or break it in Joburg, and then go home.’ So he resigned, and Juluka came to an end —and I was still full of the fire of music and dance.”

So Clegg founded a new group called Savuka — which means “We Have Risen” in Zulu. Savuka had ardent love songs, like the swooning “Dela,” but many of the band’s tunes, like “One (Hu)Man, One Vote” and “Warsaw 1943 (I Never Betrayed the Revolution),” were explicitly political.

“Savuka was launched basically in the state of emergency in South Africa, in 1986,” Clegg observed. “You could not ignore what was going on. The entire Savuka project was based in the South African experience and the fight for a better quality of life and freedom for all.”

Long after Nelson Mandela was freed from prison and had become president of South Africa, he danced onstage with Savuka to that song that Clegg had written for him.

YouTube

Clegg went on to a solo career. But in 2017, he announced he’d been fighting cancer. And he made one last international tour that he called his “Final Journey.”

The following year, dozens of musician friends and admirers — including Dave Matthews, Vusi Mahlasela, Peter Gabriel, and Mike Rutherford of Genesis — put together a charity single to honor Clegg. It’s benefited primary school education in South Africa.

YouTube

Clegg never shied away from being described as a crossover artist. Instead, he embraced the concept.

“I love it,” he said. “I love the hybridization of culture, language, music, dance, choreography. If we look at the history of art, generally speaking, it is through the interaction of different communities, cultures, worldviews, ideas and concepts that invigorates styles and genres and gives them life and gives people a different angle on stuff that was really, just, you know, being passed down blindly from generation to generation.”

Johnny Clegg didn’t do anything blindly. Instead, he held a mirror up to his nation — and urged South Africa to redefine itself.

What Did Wimbledon Teach Us About Genius?

Matthias Hangst/Getty Images

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt of Planet Money’s newsletter. You can sign up here.

Sunday’s tennis championship at Wimbledon between Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer lasted nearly five hours, a record. It finished with a 12-12 tie in the final set, triggering a first-to-seven tiebreaker. For tennis fans, it was an epic struggle between legends in a storybook setting. The weather was perfect, and the hats were divine. For readers of David Epstein’s new book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, however, it was an academic nail-biter, a test case in a simmering war between specialists and generalists.

Range argues that professional success in most fields is not primarily the product of intense specialization but of generalization, of the cross-pollination of ideas and experiences. Range is an ode to late starters, like Vincent van Gogh, who wandered Europe and failed at all kinds of things, including preaching, before changing the art of painting. It’s about the NASA scientists who failed to prevent the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle, because they couldn’t operate outside the discipline of their training. It extols violinists who start late and polymaths like Charles Darwin.

Epstein is also the author of The Sports Gene, about genetics and outcomes in athletics. Taken together, The Sports Gene and Range form something like a rebuttal to Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and the whole gospel of the 10,000 hours, which suggests that mastery can be achieved only through consistent, unwavering focus. (The two authors, in their own classic bout, actually spent a lecture arguing about generalization and specialization at a sports conference this year. You can watch it here.) Range, like Outliers, is a book about ideas, success and brilliance, and both books rely on zillions of academic studies.

And it’s about sports, of course, our most measured form of success, with a stop on the tennis court. The book opens with a story about Federer, who is described as the antithesis of Tiger Woods. (Epstein says he titled his book proposal Tiger vs. Roger.) Tiger Woods played nothing but golf, starting at around 2 years old. Federer, Epstein writes, was raised on a variety of sports. His mother specifically discouraged him from specializing in tennis. He was steered away from playing more competitive matches so he could hang out with his friends. His mother often didn’t even watch him play.

Increasingly, writes Epstein, research about sports in particular and many fields in general is finding that early specialization more often leads to burnout and skill mismatches than success. The better path, statistically, is early and wide “sampling.” It matches people to the best skills. It allows disciplines to inform one another. The numbers suggest this is true for most professional athletes, and, of course, we all want it to be true. Specialization is grueling, relentless and not really that charming.

But!

Djokovic won. Beat Federer at the end of five hours by one point.

And Djokovic is a specialist, in its most extreme form. There are no accounts of Djokovic dabbling, testing a bunch of different sports. A child prodigy, he picked up tennis at 4 and never strayed. At 7, he was interviewed for a television spot in Serbia. “Tennis is my job,” he said, according to Sports Illustrated. “My goal in tennis is to become No. 1.” He had no other interests.

Bummer. But, still, Range is a delight to read because it tells us what we want to learn: that aimlessness is the path to greatness, that our distractibility is not our weakness but our secret power, that genius and perfection can show up for us with luck, as long as we’re just willing to amble around enough.

And you could hear that wish in the crowd, which was cheering for the lovely-to-watch Federer. No one wants to be Djokovic, the anxiety-ridden grinder. But he does seem to win a lot.

If you’d just finished Range and were pumped to dabble, and maybe get started on greatness later, Wimbledon was a real heartbreaker.

Did you enjoy this newsletter? Well, it looks even better in your inbox! You can sign up here.