California Jury Awards $2 Billion To Couple In Roundup Weed Killer Cancer Trial

Containers of Roundup are displayed on a store shelf in San Francisco. A third California jury has awarded a multimillion-dollar court judgment against the herbicide.

Haven Daley/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Haven Daley/AP

A California jury has awarded a couple more than $2 billion in a verdict against Monsanto, a subsidiary of Bayer. This is the third recent court decision involving claims that the company’s Roundup weed killer caused cancer.

The jury in Alameda County, just east of San Francisco, ruled that the couple, Alva and Alberta Pilliod of Livermore, California, contracted non-Hodgkins lymphoma due to their use of the glyphosate-based herbicide. They were each awarded $1 billion in punitive damages and an additional $55 million in collective compensatory damages.

Many legal experts believe the damages will be drastically reduced on appeal.

The verdict represents the third such legal setback for the company in California since mid-2018. In March, a San Francisco jury awarded a man $80 million who blamed his cancer on his extensive use of Roundup. In August 2018, another San Francisco jury awarded $289 million to a fourth plaintiff. On appeal a judge later slashed that payout to $78 million. Bayer is appealing each of these verdicts. And the company insists there is no link between Roundup and non-Hodgkins’s lymphoma.

“Bayer is disappointed with the jury’s decision and will appeal the verdict in this case, which conflicts directly with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s interim registration review decision released just last month, the consensus among leading health regulators worldwide that glyphosate-based products can be used safely and that glyphosate is not carcinogenic, and the 40 years of extensive scientific research on which their favorable conclusions are based,” the company said in a statement.

At least one environmental group praised the verdict.

Ken Cook, president of the Environmental Working Group said “The cloud hanging over Bayer will only grow bigger and darker, as more juries hear how Monsanto manipulated its own research, colluded with regulators and intimidated scientists to keep secret the cancer risks from glyphosate.”

Four year ago, a United Nations-sponsored scientific agency declared that Roundup probably causes cancer. As NPR’s Dan Charles reported, the finding from the International Agency for Research on Cancer caused Monsanto to launch a fierce campaign to discredit the IARC’s conclusions.

“Internal company emails, released as part of a lawsuit against the company, show how Monsanto recruited outside scientists to co-author reports defending the safety of glyphosate, sold under the brand name Roundup. Monsanto executive William Heydens proposed that the company ‘ghost-write’ one paper. In an email, Heydens wrote that ‘we would be keeping the cost down by us doing the writing and they would just edit & sign their names so to speak.’ Heydens wrote that this is how Monsanto had ‘handled’ an earlier paper on glyphosate’s safety.”

More than 13,000 other lawsuits have been filed against its subsidiary, Monsanto, the maker of Roundup.

After three jury verdicts in California, a trial is scheduled for August in St. Louis County in Missouri, the site of Monsanto’s former headquarters.

States Sue Drugmakers Over Alleged Generic-Price-Fixing Scheme

Jose A. Bernat Bacete/Getty Images

Connecticut Attorney General William Tong has a skin condition called rosacea, and he says he takes the antibiotic doxycycline once a day for it.

In 2013, the average market price of doxycycline rose from $20 to $1,829 a year later. That’s an increase of over 8,000%.

Tong alleges in a new lawsuit that this kind of price jump is part of an industrywide conspiracy to fix prices.

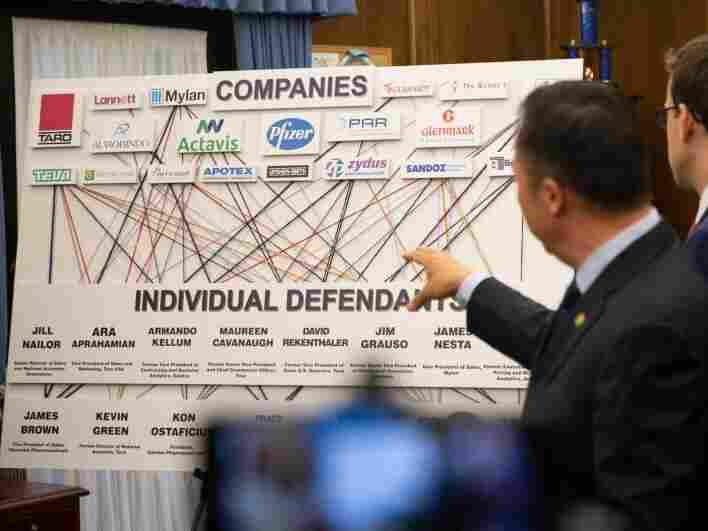

The suit is a whopper — at least 43 states are suing 20 companies, and the document is over 500 pages long. It was filed Friday in the U.S. District Court in Connecticut.

The lawsuit alleges that sometimes one company would decide to raise prices on a particular drug, and other companies would follow suit. Other times, companies would agree to divide up the market rather than competing for market share by lowering prices.

It says these kind of activities have been happening for years and that companies would avoid creating evidence by making these agreements on golf outings or during “girls nights outs” or over text message.

In several examples, the suit cites call logs between executives at different companies, showing a flurry of phone calls right before several companies would all raise prices in lockstep.

All of this, according to the lawsuit, resulted “in many billions of dollars of harm to the national economy.”

Connecticut Attorney General William Tong says the generic drug industry is profiting “in a highly illegal way” from Americans. Tong is at the forefront of a multistate lawsuit filed May 10 that alleges companies worked together to set prices.

Frankie Grazian/Connecticut Public Radio

hide caption

toggle caption

Frankie Grazian/Connecticut Public Radio

Consumers don’t always notice when a generic drug’s price increases rapidly. People without insurance, of course, pay full price, but even people with insurance can feel the impact.

“More people than ever before are paying based on the price of the drugs,” explains Stacie Dusetzina, a professor at Vanderbilt University who studies drug pricing. Often, patients have to meet a deductible before their health plan’s coverage kicks in, so “they pay full price until they reach a certain level of spending, or they pay a percentage of the drug’s price — we call that a coinsurance.”

Surveys show more Americans are having trouble paying out-of-pocket medical costs. The average annual deductible in job-based health plans has quadrupled in the past 12 years and now averages $1,300.

But, Dusetzina says, even if you only pay a modest copay — such as $5 for every prescription you pick up — if your insurance company is paying more for prescription drugs, it can raise your health plan’s premiums the following year. “So ultimately these costs do get borne by the consumer in some way,” she says.

Dusetzina says what this lawsuit alleges is “very disappointing” — a situation in which consumers put up with the high price of branded drugs because of the implicit promise that a generic is coming some day and will eventually bring the price down.

But that outcome doesn’t happen automatically; it relies on healthy competition and market forces to work. If there’s only one generic version available, that drugmaker can set the price at pretty much the same level as the brand name.

“The higher the number of competitors, the more we see price reductions from the branded drug price,” she says. “So the magic number seems to be around four manufacturers.”

And that assumes those drugmakers aren’t talking to each other and agreeing to coordinate rather than compete.

The main drugmaker cited in the lawsuit is Teva, an Israeli company. In a statement, Kelley Dougherty, vice president of communications and brand, Teva North America, told NPR that the company is reviewing the allegations internally and that Teva “has not engaged in any conduct that would lead to civil or criminal liability.”

The company has also asserted that there’s nothing new here. It’s true that the new lawsuit is similar to past lawsuits, though none of them included so many states as plaintiffs.

Tong has emphasized that the investigation is ongoing. Given the amount of political appetite there is to bring drug prices down, there are certainly more lawsuits to come.