Fentanyl-Linked Deaths: The U.S. Opioid Epidemic's Third Wave Begins

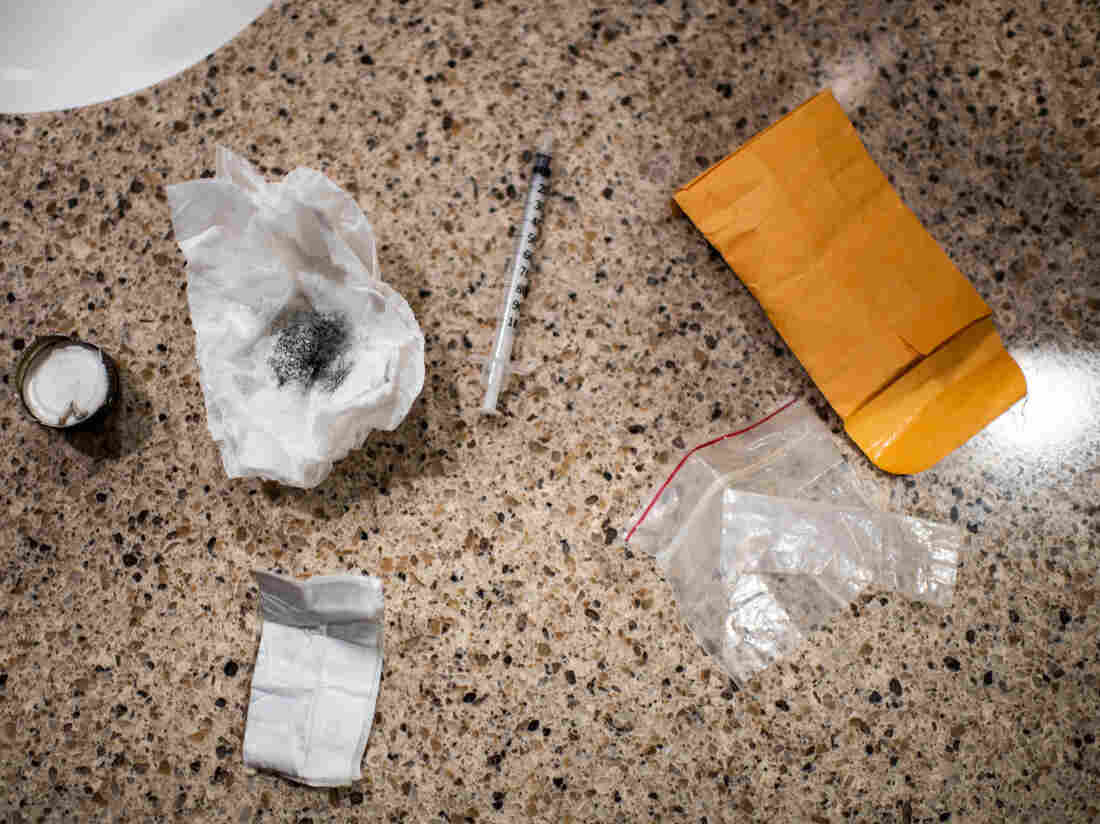

Authorities intercepted a woman using this drug kit in preparation for shooting up a mix of heroin and fentanyl inside a Walmart bathroom last month in Manchester, N.H. Fentanyl offers a particularly potent high but also can shut down breathing in under a minute.

Salwan Georges/Washington Post/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Salwan Georges/Washington Post/Getty Images

Men are dying after opioid overdoses at nearly three times the rate of women in the United States. Overdose deaths are increasing faster among black and Latino Americans than among whites. And there’s an especially steep rise in the number of young adults ages 25 to 34 whose death certificates include some version of the drug fentanyl.

These findings, published Thursday in a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, highlight the start of the third wave of the nation’s opioid epidemic. The first was prescription pain medications, such as OxyContin; then heroin, which replaced pills when they became too expensive; and now fentanyl.

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that can shut down breathing in less than a minute, and its popularity in the U.S. began to surge at the end of 2013. For each of the next three years, fatal overdoses involving fentanyl doubled, “rising at an exponential rate,” says Merianne Rose Spencer, a statistician at the CDC and one of the study’s authors.

Spencer’s research shows a 113 percent average annual increase from 2013 to 2016 (when adjusted for age). That total was first reported late in 2018, but Spencer looked deeper with this report into the demographic characteristics of those people dying from fentanyl overdoses.

Loading…

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

Increased trafficking of the drug and increased use are both fueling the spike in fentanyl deaths. For drug dealers, fentanyl is easier to produce than some other opioids. Unlike the poppies needed for heroin, which can be spoiled by weather or a bad harvest, fentanyl’s ingredients are easily supplied; it’s a synthetic combination of chemicals, often produced in China and packaged in Mexico, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. And because fentanyl can be 50 times more powerful than heroin, smaller amounts translate to bigger profits.

Jon DeLena, assistant special agent in charge of the DEA’s New England Field Division, says one kilogram of fentanyl, driven across the southern U.S. border, can be mixed with fillers or other drugs to create six or eight kilograms for sale.

“I mean, imagine that business model,” DeLena says. “If you went to any small-business owner and said, ‘Hey, I have a way to make your product eight times the product that you have now,’ there’s a tremendous windfall in there.”

For drug users, fentanyl is more likely to cause an overdose than heroin because it is so potent and because the high fades more quickly than with heroin. Drug users say they inject more frequently with fentanyl because the high doesn’t last as long — and more frequent injecting adds to their risk of overdose.

Fentanyl is also showing up in some supplies of cocaine and methamphetamines, which means that some people who don’t even know they need to worry about a fentanyl overdose are dying.

There are several ways fentanyl can wind up in a dose of some other drug. The mixing may be intentional, as a person seeks a more intense or different kind of high. It may happen as an accidental contamination, as dealers package their fentanyl and other drugs in the same place.

Or dealers may be adding fentanyl to cocaine and meth on purpose, in an effort to expand their clientele of users hooked on fentanyl.

“That’s something we have to consider,” says David Kelley, referring to the intentional addition of fentanyl to cocaine, heroin or other drugs by dealers. Kelley is deputy director of the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. “The fact that we’ve had instances where it’s been present with different drugs leads one to believe that could be a possibility.”

The picture gets more complicated, says Kelley, as dealers develop new forms of fentanyl that are even more deadly. The new CDC report shows dozens of varieties of the drug now on the streets.

The highest rates of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths were found in New England, according to the study, followed by states in the Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest. But fentanyl deaths had barely increased in the West — including in Hawaii and Alaska — as of the end of 2016.

Researchers have no firm explanations for these geographic differences, but some people watching the trends have theories. One is that it’s easier to mix a few white fentanyl crystals into the powdered form of heroin that is more common in eastern states than into the black tar heroin that is sold more routinely in the West. Another hypothesis holds that drug cartels used New England as a test market for fentanyl because the region has a strong, long-standing market for opioids.

Spencer, the study’s main author, hopes that some of the other characteristics of the wave of fentanyl highlighted in this report will help shape the public response. Why, for example, did the influx of fentanyl increase the overdose death rate among men to nearly three times the rate of overdose deaths among women?

Some research points to one particular factor: Men are more likely to use drugs alone. In the era of fentanyl, that increases a man’s chances of an overdose and death, says Ricky Bluthenthal, a professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

“You have stigma around your drug use, so you hide it,” Bluthenthal says. “You use by yourself in an unsupervised setting. [If] there’s fentanyl in it, then you die.”

Traci Green, deputy director of Boston Medical Center’s Injury Prevention Center, offers some other reasons. Women are more likely to buy and use drugs with a partner, Green says. And women are more likely to call for help — including 911 — and to seek help, including treatment.

“Women go to the doctor more,” she says. “We have health issues that take us to the doctor more. So we have more opportunities to help.”

Green notes that every interaction with a health care provider is a chance to bring someone into treatment. So this finding should encourage more outreach, she says, and encourage health care providers to find more ways to connect with active drug users.

As to why fentanyl seems to be hitting blacks and Latinos disproportionately as compared with whites, Green mentions the higher incarceration rates for blacks and Latinos. Those who formerly used opioids heavily face a particularly high risk of overdose when they leave jail or prison and inject fentanyl, she notes; they’ve lost their tolerance to high levels of the drugs.

There are also reports that African-Americans and Latinos are less likely to call 911 because they don’t trust first responders, and medication-based treatment may not be as available to racial minorities. Many Latinos say bilingual treatment programs are hard to find.

Spencer says the deaths attributed to fentanyl in her study should be seen as a minimum number — there are likely more that weren’t counted. Coroners in some states don’t test for the drug or don’t have equipment that can detect one of the dozens of new variations of fentanyl that would appear if sophisticated tests were more widely available.

There are signs the fentanyl surge continues. Kelley, with the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, notes that fentanyl seizures are rising. And in Massachusetts, one of the hardest-hit areas, state data show fentanyl present in more than 89 percent of fatal overdoses through October 2018.

Still, in one glimmer of hope, even as the number of overdoses in Massachusetts continues to rise, associated deaths dropped 4 percent last year. Many public health specialists attribute the decrease in deaths to the spreading availability of naloxone, a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

This story is part of NPR’s reporting partnership with WBUR and Kaiser Health News.

Boeing Brings 100 Years Of History To Its Fight To Restore Its Reputation

Boeing 737 Max jets are grounded at Sky Harbor International Airport in Phoenix on March 14.

Matt York/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Matt York/AP

Boeing’s bestselling jetliner, the 737 Max, has crashed twice in six months — the Lion Air disaster in October and the Ethiopian Airlines crash this month. Nearly 350 people have been killed, and the model of plane has been grounded indefinitely as investigations are underway.

Boeing has maintained the planes are safe. But trust — from the public, from airlines, from pilots and regulators — has been shaken.

So far, experts say, Boeing has mishandled this crisis but has the opportunity to win back confidence in the future.

Boeing bet heavily on the Max. The plane was designed to compete with a fuel-efficient jetliner from rival Airbus, and analysts have estimated it is responsible for nearly a third to 40 percent of Boeing’s profits.

Reporting from The Seattle Times suggests Boeing’s urgency to get the plane to market pressured the Federal Aviation Administration, which may have contributed to lax oversight on safety. Boeing disputes this.

But many people are raising questions about how cozy the manufacturer is with the FAA and how committed the company has been to protecting safety.

“I think that Boeing currently is flunking the ‘can-we-trust-you test,’ ” says Sandra Sucher, a professor of management practice at Harvard Business School.

Trust includes multiple dimensions, she says: trusting a company to be competent, to be motivated to do the right thing, to use fair methods to achieve its goals, and to hold itself accountable when things go wrong. On every level, by her reckoning, Boeing is falling short.

It’s possible to win back that trust, she says — but only if the company holds itself accountable.

“The worst thing that they could do would be to maintain their insistence that this plane is safe to fly,” she says. “I think they have to start with a clear statement that they take accountability for what happened.”

Boeing has supported the FAA’s decision to ground its planes and is providing assistance to the ongoing investigations. But the company continues to stand behind the safety of its product. In a letter Monday, CEO Dennis Muilenburg described a commitment to making “safe airplanes even safer.”

“Together, we’ll keep working to earn and keep the trust people have placed in Boeing,” he wrote.

Sucher says Boeing needs to start by rebuilding confidence within the company itself — convincing employees they are protected if they highlight problems. Once that trust is rebuilt, the company can start looking outward, where it has multiple audiences to convince of its reliability.

“Boeing is working in a dual lane when it comes to restoring its brand,” says Shashank Nigam, the CEO of aviation consultant firm SimpliFlying.

On one hand, he says, there are “airlines and regulators, who are the key stakeholders” — those who actually purchase and monitor the planes.

But members of the general public are “the ultimate customers,” Nigam says, and Boeing ultimately needs to win their confidence, too.

In 1919, Bill Boeing (holding the mailbag on right) and Eddie Hubbard flew the first international mail flight from Vancouver, British Columbia, to Seattle in the Boeing Model C, the company’s first production plane.

Boeing

hide caption

toggle caption

Boeing

A history of turbulence — and soaring success

Analysts expect Boeing to weather this storm. The company has certainly survived other rough patches in its century-long history.

It was founded in 1916, just 13 years after the Wright brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk. Bill Boeing started out making wood-and-canvas seaplanes out of a boathouse. He got a big boost from military orders during World War I, explains Russ Banham, a financial journalist and the author of Higher, a history of the company.

“Then the war ended. The government orders came to a standstill and the company actually was forced to make furniture … and wooden boats,” Banham says.

But Boeing hung on until World War II, and another infusion of U.S. military funds — and deeper ties to the U.S. government.

A U.S. Air Force Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, circa 1945.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

A period of postwar prosperity was followed by a low point in the early 1970s, during a recession that struck the entire aerospace industry. For a year and a half, Banham says, Boeing didn’t get a single order. The company laid off so many people from its facilities in Seattle that locals put up a billboard: “Will the last person leaving Seattle — turn out the lights.”

Still, Boeing was resilient, building wind turbines and even getting into the housing industry, before roaring back to become a profitable, influential industrial powerhouse. Today it’s America’s largest exporter.

More recently, Boeing survived the troubled launch of the 787 Dreamliner. Batteries onboard could catch fire, a problem that prompted the FAA to ground the planes. Christine Negroni, an aviation writer and the author of The Crash Detectives, called it a “fiasco.”

But nobody died in the Dreamliner battery incidents. Negroni says Boeing is in a tougher situation today.

“I don’t think it could be worse for Boeing right now,” she says. “Two new airplanes. Two big problems, two groundings. It doesn’t live up to our expectations of Boeing and it’s certainly shaken the confidence of travelers worldwide.”

“People are going to forget”

Passengers might be alarmed today. But historical precedents suggest that after some time has passed, the public will be willing to get back on the 737 Max.

The world’s very first jetliner — the de Havilland Comet — had a fatal flaw. Three planes disintegrated, killing all onboard, before engineers figured out the problem and fixed it. A redesigned Comet 4 flew for decades.

And in the 1970s, the DC-10 (produced by then-Boeing rival McDonnell Douglas) suffered a series of crashes tied to design flaws. Problems with the plane’s cargo door brought down two planes, killing nearly 350 people in the second accident. Then, in 1979, a combination of maintenance and design flaws caused the then-deadliest aviation accident in U.S. history.

The DC-10 had a horrible reputation. It earned nicknames like “death cruiser,” says aviation reporter Bernie Leighton.

But problems in the plane’s design were fixed. “When they were rectified, the DC-10 went on to have a very illustrious career with multiple airlines,” he says.

British entrepreneur Freddie Laker waves a flag in front of a Douglas DC-10 in 1977 at the launch of his no-frills “Skytrain” service. The DC-10 had already experienced multiple catastrophes as a result of design flaws, and another deadly crash came two years later.

Dennis Oulds/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Dennis Oulds/Getty Images

Both the Comet and the DC-10 were eventually eclipsed by other planes with better technology, and their manufacturers were acquired by competitors (McDonnell Douglas, in fact, was purchased by Boeing). But the planes themselves spent decades in service, and a version of the DC-10 is still in use by the U.S. Air Force.

So once the investigations into the 737 Max are concluded, and problems are fixed, Leighton has a simple prediction.

“People are going to forget,” he says. “People are just going to see it as another 737. They’re going to take their kids to Disneyland; they’re going to focus on how amazing the vacation was and how much they don’t like the TSA. They’ll forget they ever flew on a 737 Max.”

Can Woodstock 50 'Recreate The Magic' Of The Original Festival?

Jay-Z performs on stage during ‘On the Run II’ tour in 2018. The rapper is among the headliners of Woodstock 50.

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

It’s been 50 years since Woodstock Music & Arts Festival. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of three days of peace, love and music, Woodstock 50 will take place this Aug. 16–18, 2019 in Watkins Glen, N.Y. Festival co-founder Michael Lang has announced the official lineup for the anniversary festival with Jay-Z, Dead & Company and The Killers as headliners. Rounding out the list of performers are Miley Cyrus, Imagine Dragons, The Black Keys and Chance The Rapper as well as acts like Santana who performed at the seminal fest five decades ago. But what makes this 50th anniversary lineup special among a saturated field of music festivals this?

“They’re trying to recreate the magic and some of the cultural dominance that the original Woodstock did,” NPR Music’s Stephen Thompson says, noting that organizers are not only working in the shadow of the behemoth that was the original event, but also in the shadow of “the debacle that is Woodstock 99” which was notorious for violence, destruction and sexual assault cases.

In the years since the original Woodstock, the festival’s symbolism of peace and love has been romanticized in pop culture. As Thompson notes, no matter who’s on the bill, carrying on the legacy of the original Woodstock is incredibly hard. “They’re trying, I think, to feed a lot of mouths at once,” Thompson says of the variety in this year’s lineup compared to the gathering of 400,000 people back in 1969. “In order to attract 400,000 in this market place, you have to please a lot of people at once.”

As for clear comparisons to the original fest? “In the announcement of this new Woodstock lineup, there was conversation about the parallels between the political situation in 1969 and the political situation in the present,” Thompson notes. “So, I’m sure there’s going to be an attempt to sort of tie the two together and bring out some of the activism.”

Even though summer festival season is more crowded than ever, Thompson thinks Woodstock 50 will stand out because of its historical name recognition and reverberations to be a “siren song to anyone who feels some kind of attachment” to the word ‘Woodstock’ and it’s music history.

Listen to the entire conversation at the audio link.

There's Word Of Another Record-Shattering Baseball Deal In The Works

The Los Angeles Angels reportedly are very close to signing Mike Trout to a record breaking 12-year, $430 million deal.

RACHEL MARTIN, HOST:

Can a single baseball player really be worth $430 million? The Los Angeles Angels may soon find out.

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

The Angels are in the process of finalizing a deal to re-sign Mike Trout. If the center fielder commits, the $430 million price would set records. That would be his pay over the course of 12 years.

MARTIN: We asked another Mike, Mike Pesca – the Mike Trout of sports commentators – how the Angels star could command so much.

MIKE PESCA, BYLINE: So beginning with his first full season, when he was all of 20, Mike Trout finished second in the MVP race, second again, then first, then second, then first, then fourth, then second. It is unprecedented for a guy who is 26 – he’s 27 now – to put together that body of work. By comparison, Babe Ruth finished in the top five a total of three times in his career. Mike Trout is off-the-charts, Hall-of-Fame good. Literally, if this guy retires tomorrow, he really should make the Hall of Fame just on his merits.

INSKEEP: Of course, past performance is no guarantee of future results, but the Angels can hope.

PESCA: Mike Trout is a bargain at what they’re paying him – an absolute bargain. Forget the sticker shock. The return on the investment is a bargain by anyone’s metrics. What this does is it allows and, in fact, forces the Angels to build a great team, the team that Mike Trout deserves. You are not going to get as good a bargain with other free agents. It’s just impossible because the value that Mike Trout’s contract gives you is not easy to replicate. But that’s OK. This can be a team that makes the playoffs for years to come.

MARTIN: Mike Pesca, host of Slate’s podcast “The Gist” and author of “Upon Further Review: The Greatest What-Ifs In Sports History.”

(SOUNDBITE OF ELEPHANT GYM’S “SPRING RAIN”)

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.