The Rams And The Patriots Will Face Off For Super Bowl LIII

Los Angeles Rams head coach Sean McVay celebrates with Greg Zuerlein after a game-winning field goal during overtime of the NFL’s NFC championship game against the New Orleans Saints on Sunday.

David J. Phillip/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

David J. Phillip/AP

The Los Angeles Rams and the New England Patriots will face off in this year’s Super Bowl after winning the NFC and AFC conference championships, respectively, on Sunday.

The Rams, who overcame a 13-point deficit to beat the Saints, last played in the Super Bowl in 2002 — against none other than the Patriots. The St. Louis Rams won the NFL title two years before that.

The Patriots defeated the Chiefs to return to the Super Bowl for a third consecutive year.

Los Angeles Rams beat New Orleans Saints

Two field goals, a crucial interception and a widely contested pass interference call from officials, helped the Rams oust the Saints.

What the team lacked offensively, Greg Zuerlein made up for with timely kicking. In the final 15 seconds of regulation, the placekicker booted a tying 48-yard kick, sending the game into overtime. In the extra period, Zuerlein nailed a 57-yard field goal to seal a 26-23 victory.

On the first drive of overtime, the Saints lost possession after safety John Johnson III picked off Drew Brees’ lofty pass meant for wide receiver Michael Thomas.

“It’s unbelievable, man. I can’t put it into words,” Rams quarterback Jared Goff told The Associated Press. “The defense played the way they did to force it to overtime. The defense gets a pick and Greg makes a 57-yarder to win it. That was good from about 70. Unbelievable.”

One call cast a long shadow over the game. Referees failed to call what both Saints supporters and sports analysts overwhelmingly perceived as a pass interference penalty against the Rams. With the score at 20-20 in the fourth quarter, Drew Brees’ pass to Tommylee Lewis fell to the ground after he was hit by Rams defensive back Nickell Robey-Coleman.

“I don’t know if there was ever [a] more obvious pass interference,” New Orleans coach Sean Payton told reporters after the game.

After the game the NFL confirmed in a call to Payton that referees made the wrong call, according to USA Today.

As the AP reports, “It was the first home playoff loss for the Saints with Brees and coach Sean Payton, who had been 6-0 in those games since their pairing began in 2006.”

The Rams will now play against the Patriots for the NFL title.

New England Patriots beat Kansas City Chiefs

In another playoff game settled in overtime, the Patriots held off the Chiefs to grab a spot in the Super Bowl for the third straight season.

After New England dominated the first half in a frigid Kansas City, the Chiefs took the lead thanks to Damien Williams’ third touchdown run of the game, forcing a frantic fourth quarter.

With 39 seconds left, running back Rex Burkhead was able to lift the Patriots ahead 31-28 — the fourth lead change of the fourth quarter.

Down to 8 seconds, Harrison Butker wrestled back the points for the Chiefs with a 39-yard field goal, taking the rally into overtime at 31-31.

The Patriots then won the coin toss to start overtime. It was the final boost New England needed for a shot at defending their NFL title. Quarterback Tom Brady kicked off a game-winning drive as Rex Burkhead took the ball for a touchdown, sealing a 37-31 victory over the Chiefs.

“Overtime, on the road against a great team,” Brady told the AP. “They had no quit. Neither did we. We played our best football at the end. I don’t know, man, I’m tired. That was a hell of a game.”

The Big Game

The Rams and the Patriots will contend for the title of Super Bowl LIII champs at the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta on Sunday, Feb. 3, airing on CBS.

Gladys Knight is scheduled to sing the national anthem. As for the intermission from nail-biting plays, pop band Maroon 5, rapper Travis Scott and Atlanta’s own Big Boi will perform at halftime.

Lack Of Data Processing During Government Shutdown Compounds Economic Effects

As the partial government shutdown drags on, more people, organizations and entire state governments are feeling the pain. The trickle-down in places like Texas blossoms as the shutdown continues.

MELISSA BLOCK, HOST:

With both House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and President Trump seemingly locked into their positions on the government shutdown, state leaders are increasingly grappling with the shutdown’s impact. NPR’s Wade Goodwyn reports now on the shutdown’s trickle-down effect on Texas.

WADE GOODWYN, BYLINE: It’s probably not the first thing that pops into one’s mind when asked to name a couple of the biggest impacts the shutdown has on the economy. You might think airline travel or the national park system. But one of the biggest economic effects has to do with information, research that the federal government produces monthly or quarterly.

PATRICK JANKOWSKI: My biggest concern right now is that with the – so many federal agencies shut down, we’re not getting the data we need to understand what’s going on with the economy.

GOODWYN: Patrick Jankowski is the senior vice president of research at the Greater Houston Partnership and the chief economist for the fourth largest city in the country.

JANKOWSKI: If you’re trying to make hiring decisions and you want to find out whether the economy is expanding, contracting or what rate it is expanding, you need the regular reports to understand that.

GOODWYN: The impact of the shutdown on the economy radiates out from the absence of federal employees. For example, more than $200 billion a year in trade moves through Texas seaports. But without the review of important paperwork by the Coast Guard – for example, the required certificates of financial responsibility – that ship’s not coming into U.S. waters.

Switch gears. Texas has a hundred billion-dollar-a-year agriculture sector. Right now is the time when farmers decide what crops and how much of each crop to plant. Luis Ribera is a professor and agricultural economist at Texas A&M University.

LUIS RIBERA: The different agencies in USDA – they collect a lot if information, which – we use it to analyze and forecast. They’re very reliable. They’re unbiased.

GOODWYN: Ribera says it says if farmers are now playing poker blindfolded. They’re going to have to make their bets, but they have to guess what cards they’re holding. Take soybeans, for example. Texas is the largest producer, and soybean farmers want and need to know how much China’s been buying or not buying.

RIBERA: Usually, the Foreign Agricultural Service data comes about two months behind, so we should’ve gotten information by the first week in January. Well, we didn’t. So we really don’t know. By October, we were down by quite a bit. But now, we have a truce, and we wanted to see how much more soybeans we’re sending. And, of course, that’s going to impact the price of the products, not only soybeans, all different products.

GOODWYN: The oil and gas industry in Texas remains sound. Projects under review have been slowed. But, with the cost of a barrel of oil in the low 50s, producers are making money. With both American and Southwest Airlines based in Dallas-Fort Worth, the state is host to two powerhouse carriers. And analysts agree the industry’s weak point in relation to the shutdown is TSA airport security. It’s one of the lowest-paying federal agencies, and a second missed paycheck is certain. Joseph DeNardi is the airline’s analyst for Stifel Financial.

JOSEPH DENARDI: Yeah. I’m sure, at some point, you can’t expect people to show up for work if they’re not being paid. That would be the biggest risk, that, at some point, you have staffing challenges at some of the agencies that directly affect customers’ ability to fly. I don’t think we’re seeing any of that yet.

GOODWYN: Delta announced it would lose $25 million in revenue in January. The industry is expected to have another excellent year. Maybe it will. Maybe it won’t. The length of the shutdown could decide.

Wade Goodwyn, NPR News, Dallas.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Medical Students Push For More LGBT Health Training To Address Disparities

Sarah Spiegel, a third-year student at New York Medical College, pushed for more education on LGBT health issues for students.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

When Sarah Spiegel was in her first year at New York Medical College in 2016, she sat in a lecture hall watching a BuzzFeed video about what it’s like to be an intersex or a transgender person.

“It was a good video, but it felt inadequate for the education of a class of medical students, soon to be doctors,” says Spiegel, now in her third year of medical school.

The video, paired with a 30-minute lecture on sexual orientation, was the only LGBT-focused information Spiegel and her fellow classmates received in their foundational course.

“It’s not adequate,” Spiegel remembers thinking. By her second year, after she became president of the school’s LGBT Advocacy in Medicine Club, she rallied a group of her peers to approach the administration about the lack of LGBT content in the curriculum.

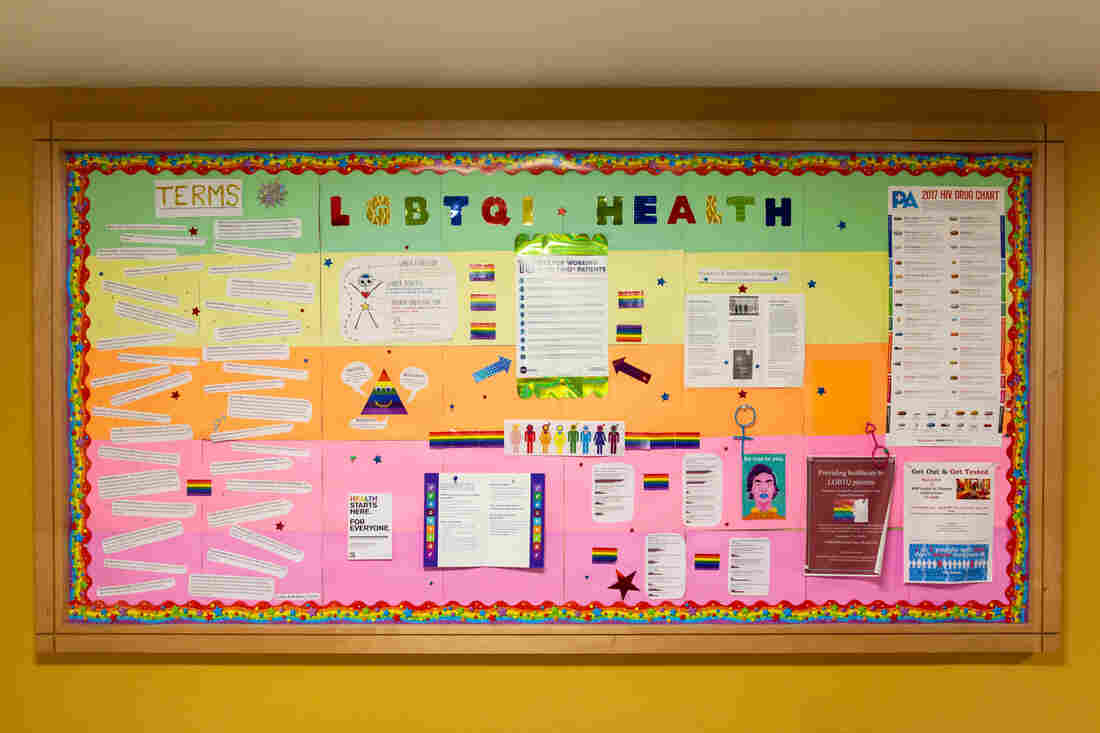

Spiegel and her friends created an LGBTQI health board of information which hangs in a hallway on campus at New York Medical College.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

Spiegel says administrators were “amazingly receptive” to her presentation, and she quickly gained student and faculty allies. As a result, the school went from one and a half hours of LGBT-focused content in the curriculum to seven hours within a matter of two years, according to Spiegel. Spiegel says she doesn’t think the change would have happened had the students not pushed for it.

According to a number of studies, medical schools do a poor job of preparing future doctors to understand the LGBT population’s unique needs and health risks. And, a 2017 survey of students at Boston University School of Medicine found their knowledge of transgender and intersex health to be lesser than that of LGB health.

Meanwhile, LGBT people — and transgender people in particular – face disproportionately high rates of mental illness, HIV, unemployment, poverty, and harassment, according to Healthy People 2020, an initiative of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. And a poll conducted by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found 1 in 5 LGBT adults has avoided medical care due to fear of discrimination.

“The health of disparity populations is something that really should be the focus of health profession students,” says Dr. Madeline Deutsch, an associate professor of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Deutsch directs UCSF’s Transgender Care program, and she says medical schools already do a fairly good job of addressing some disparities, like those based on race, ethnicity, and socio-economic status.

But, she says, “Sexual and gender minorities have historically been not viewed as a key population, and that’s unfortunate because of the size of the population, and because of the extent of the disparities that the population faces.” (About 0.6 percent of the U.S. population – or 1.4 million adults – identifies as transgender.)

The extent of LGBT education medical students receive varies greatly, but a 2011 study found that the median time spent on LGBT health was five hours. The topics most frequently addressed include sexual orientation, safe sex, and gender identity, whereas transgender-specific issues, including gender transitioning, were most often ignored. And some medical students receive no LGBT education at all.

“There’s not really a consistent curriculum that exists around this content,” says Deutsch.

As a result, physicians often feel inadequately trained to care for LGBT patients. In a 2018 survey sent out to 658 students at New England medical schools, around 80 percent of respondents said they felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” with the medical treatment of gender and sexual minority patients.

Even at UCSF, which has long been at the forefront of LGBT health care, Deutsch says there’s still a need to insert more transgender health care into the mandatory curriculum. Right now, when medical schools teach about LGBT health issues, it’s usually through special elective courses or lectures taught at night or during lunch, and often by the students themselves.

“How do we take it out of the lunchtime unit?” asks Jessica Halem, the LGBT program director at Harvard Medical School. That question drives Harvard Medical School’s new Sexual and Gender Minorities Health Equity Initiative, a three-year plan to assess the core medical school curriculum and to identify opportunities to better instruct on the health of sexual and gender minorities.

“Students are getting the information. But some of them are having to do a lot of extra work to get that during their medical school experience,” says Halem.

The Harvard initiative, announced in December 2018, has been ongoing for about six months, says Halem, thanks to a $1.5 million gift from Perry Cohen, a transgender man. According to Halem, Cohen hopes that Harvard’s learnings will be shared with medical schools across the country, especially with ones with less robust LGBT health education programs.

Studies have shown that when medical students learn about transgender health issues, they feel better equipped to treat transgender patients. For example, when Boston University School of Medicine added transgender health content to a second-year endocrinology course, students reported a nearly 70 percent decrease in discomfort with providing transgender care.

And now, Halem says, each incoming class at Harvard Medical School is increasingly adamant that they learn about LGBT health.

“The main first driver truly was medical students organizing and saying ‘Hey, I need the curriculum to reflect the kind of medicine that I came here to study,’ ” Halem says.

The amount of LGBT education medical students receive varies greatly. A 2015 study found that, on average, medical students receive five hours of LGBT-focused education. The curriculum at New York Medical College went from an hour and a half of LGBT topics in health care to over seven hours.

Mengwen Cao for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Mengwen Cao for NPR

Those were the thoughts running through Spiegel’s head in her own preclinical years at New York Medical College. Shortly after becoming the president of her school’s LGBT health club, she joined The American Medical Student Association’s Gender and Sexuality Committee as the LGBTQ Advocacy Coordinator to bring curricular change to other medical schools in the New York area.

Conversations with her transgender partner also inspired Spiegel to introduce more trans-specific topics into her school’s curriculum.

“His experience definitely varied by how much providers knew,” Spiegel says. It was often as simple as getting his pronouns correct, she says, and even then, the same doctors’ office would mess that up again and again.

Spiegel says in the past couple of years, certain disciplines have added trans-focused topics into their specialties. In the school’s behavioral health unit, for example, professors have started to address how doctors can diagnose gender dysphoria – when a person feels their assigned gender does not align with their gender identity – in their lectures.

By contrast, some disciplines have been more hesitant to change, or add content to, their existing curriculum. Spiegel’s student task-force had more difficulty influencing the pharmacology department, for example. That’s the content area where hormone therapy might be taught, Spiegel says.

One course includes a lecture about the endocrine system, Spiegel says, when the professor talks about a drug to treat precocious, or early puberty. That drug can also be used for kids undergoing transgender hormone therapy. Therefore, Spiegel says, including transgender health in the lecture might be a matter of just saying an extra sentence.

“There’s an opportunity there – they would just have to mention that it could also be used for transgender kids,” says Spiegel.

But the professor says this secondary use of the drug was “off the book,” and thus, he wouldn’t include it in his lecture. So Spiegel researched the drug herself, and sent the professor the Endocrine Society’s guidebook that talked about how the drug can be used for transgender patients. He began including the information in his lectures.

Spiegel says her interactions with this professor exemplify the challenges that medical students all over the country face when trying to introduce changes to their schools’ curricula.

“We’re getting there, but it’s slow,” says Spiegel.