Diver Sammy Lee, the first American to win gold medals in platform diving in consecutive Olympic games, was also among the country’s earliest “cultural ambassadors.” Bettmann Archive hide caption

toggle caption

Bettmann Archive

The slew of obituaries that have been published since Olympic diver Sammy Lee’s death on Friday rightly highlight his conquest over racism and indignity on the way to winning gold medals in London and Helsinki nearly 70 years ago. As Greg Louganis, Lee’s most famous protege, reflected in the Los Angeles Times, “At a time of intolerance, being Korean, he broke down racial barriers, setting an example of what it meant to be an Olympian.”

Today, when race remains lodged at the center of our national debate, Lee’s victories and his unique service to this country confirm an enduring truth in American life: One person can make a huge difference, but bigotry is never far from the surface.

In the mid-20th century, Lee’s contemporaries grasped the compelling nature of his journey from the segregated world of the pre-World War II West to U.S. Olympic champion. Federal leaders saw in Lee’s biography a weapon for fighting the Cold War against communism. While the United States tried to win the “hearts and minds” of the planet, racial turmoil and violence at home sullied the image of American democracy abroad. As Mary Dudziak, Penny Von Eschen and other scholars of Cold War civil rights have explained, flesh-and-blood examples of accomplished people of color could do much to boost the nation’s street cred around the globe.

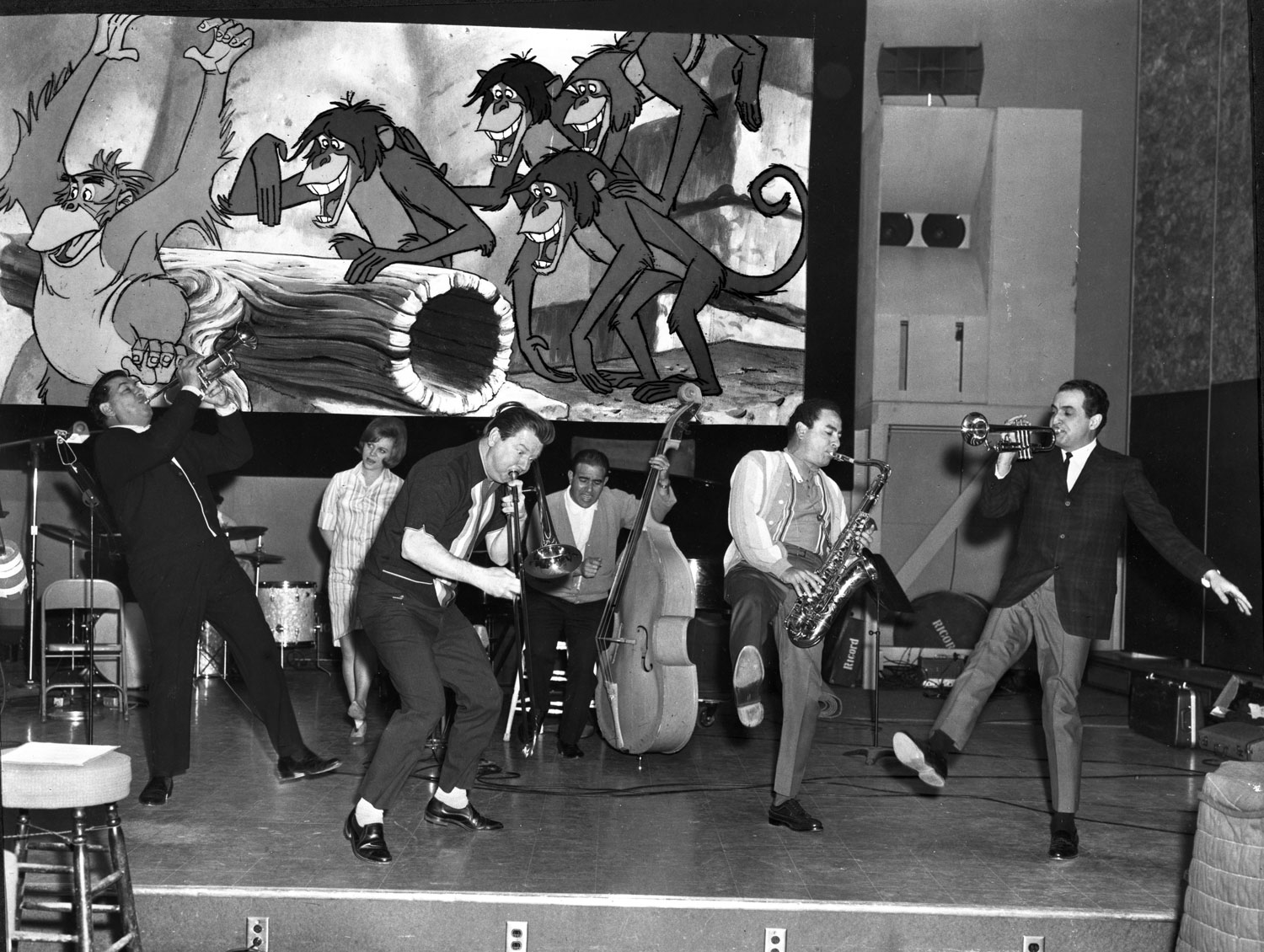

Congress passed the U.S. Information and Education Exchange Act of 1948 to do just that. The roster of racial and ethnic “success stories” enlisted by the government included the Harlem Globetrotters and jazz greats like Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong. With Asia as a major focus of U.S. foreign relations, the U.S. also turned to Asian-American emissaries, among them, ceramicist and writer Jade Snow Wong, painter Dong Kingman, the San Francisco Chinese Basketball Team, Rep. Dalip Singh Saund and Sens. Hiram Fong and Daniel Inouye.

Sammy Lee fit that bill perfectly. Not only was he a world-renowned diver, he was also in the Army, serving in Korea as an ear, nose and throat physician. In a March 1954 staff memo, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles floated the idea of recruiting Lee to work as a cultural diplomat.

“It is felt that with his oriental background, his success as an American doctor, and his international athletic reputation, he could command large and diversified [overseas] audiences,” Dulles wrote.

His colleagues agreed.

In August of that year, Lee set off on a whirlwind tour of Asia that was meant to “increase mutual understanding” between Americans and people elsewhere through the swapping of “persons, knowledge, and skills,” according to the 1948 law. Lee’s itinerary included Japan, India, Ceylon, Pakistan, Turkey, Singapore, Vietnam, Burma, Hong Kong and the Philippines.

Every stop on the months-long tour was crammed with diving exhibitions, speeches, film screenings of his Olympic feats, media interviews and even coaching sessions with young, local divers. During his week in Pakistan, for instance, Lee met with representatives of the Pakistan Swimming Federation, the Punjab Swimming Association, and the military; talked to Radio Pakistan, and dined with the Pakistan Army Medical Corps and the Rotary Club in Lahore. He also squeezed in visits to the Pakistan Army Headquarters in Rawalpindi, the Royal Pakistan Air Force training center in Risalpur, and hospitals and health care facilities. A crowd of 800 turned out to watch him perform his signature moves in Karachi.

Lee charmed his way across Asia, drawing in audiences with his laid-back personality, ready warmth and quick wit. He even poked fun at Cold War tensions. A consulate report sent to Washington from Lee’s stop in Hong Kong recorded his most uproarious anecdote: Lee’s account of his 1952 gold medal victory in Helsinki:

“There were seven judges for the diving, three from the other side of the Iron Curtain and four from our side. They saw this little runt of a guy with this Oriental face climb up on the tower and they knew I was a Korean. But they couldn’t figure out whether I was a North or South Korean. By the time they found [out], it was too late.”

Occasionally, the dispatch noted, Lee would “put in an added fillip, He would walk out on the board, stop and tell the audience, ‘Say, I forgot to tell ya. I’m South!’ “

State Department bureaucrats raved in their propaganda reports to Washington that Lee faithfully emphasized two themes. The first was that Asians in America enjoyed “the equal opportunity … to become what [they] want to become.” Second was the pride that U.S. minority groups retained for their ancestral homelands.

“My father always told me, ‘Sammy, in order to be a good American, you have to be a good Korean at the same time,’ ” Lee was quoted as saying in the Hong Kong report. The U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong wrote that Lee did this with “good humor” and “evident sincerity” and won over even the most “skeptical and sophisticated” people in the audience.

Why did Lee turn so many heads on his junket? U.S. diplomatic officials attributed his magnetism to what was an “Oriental” essence encoded in his DNA. Even as Lee proclaimed his attachment to his native country, he “possess[ed] a perhaps instinctive understanding of the Asian mind which enable[d] him to communicate immediately and fully with audiences and individuals of this area,” officials of the American Embassy in Burma hypothesized.

This was the paradox at the heart of Lee’s ambassadorship. In using him to connect the U.S. to foreign countries that way, the government reinforced the stubborn notion that Asians are never quite all-American. The longtime assumption that “Orientals” were fundamentally alien still held.

While this association may have seemed innocuous in the context of Lee’s overseas expedition, it took on a familiar tint once he returned stateside. He and his wife were blocked from buying a house in Southern California because, as one real estate agent said, “If we had a colored or Oriental family here, all hell would be raised.”

Ironically, as historian Charlotte Brooks has pointed out, Cold War considerations neutralized the xenophobic antagonism. The San Francisco Chronicle leapt to the Lees’ defense, reminding readers of the foreign-policy stakes of anti-Asian discrimination:

“Here was an American of Oriental descent demonstrating to Asians that despite Communist propaganda the United States is a land of tolerance and opportunity. The story of Major Lee’s reception in Garden Grove will embarrass our country in the eyes of the world.”

Hundreds soon flooded the couple with gestures of support and offers to move into their neighborhoods.

As we mark the 75th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, Lee’s story illuminates a relevant lesson about belonging in America. His impressive achievements were no doubt a product of hard work, perseverance and the determination, despite the hurdles, “to prove that in America, I could do anything,” as he once told the Los Angeles Times.

Yet history shows again and again how quickly national security scares can erect new barriers.

Cold War ambitions provided an important opening for Lee to be recognized, celebrated and accepted as a fellow American. But national security will always be shaky ground on which to build a case for civic inclusion, because the pendulum swings both ways for those assumed to be forever foreigners.

Many Japanese-Americans experienced this most traumatically after Pearl Harbor, when the government shipped them off to concentration camps. And with the ratcheting up of Islamophobia and indiscriminate racial and ethnic profiling in our current political moment, the well-being of our South Asian, Arab, Muslim and Sikh communities is at grave risk.

Protecting the rights of the most vulnerable among us — especially all those who might fall under the sweep of mass deportations or a Muslim registry — would be a fitting way to continue Lee’s storied struggle against racism.

Ellen Wu is associate professor of history and director of the Asian-American Studies program at Indiana University, Bloomington. She is the author of The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority.

Let’s block ads! (Why?)