Mrs. Obama Saves The Cardigan: 'The Obama Effect' In Fashion

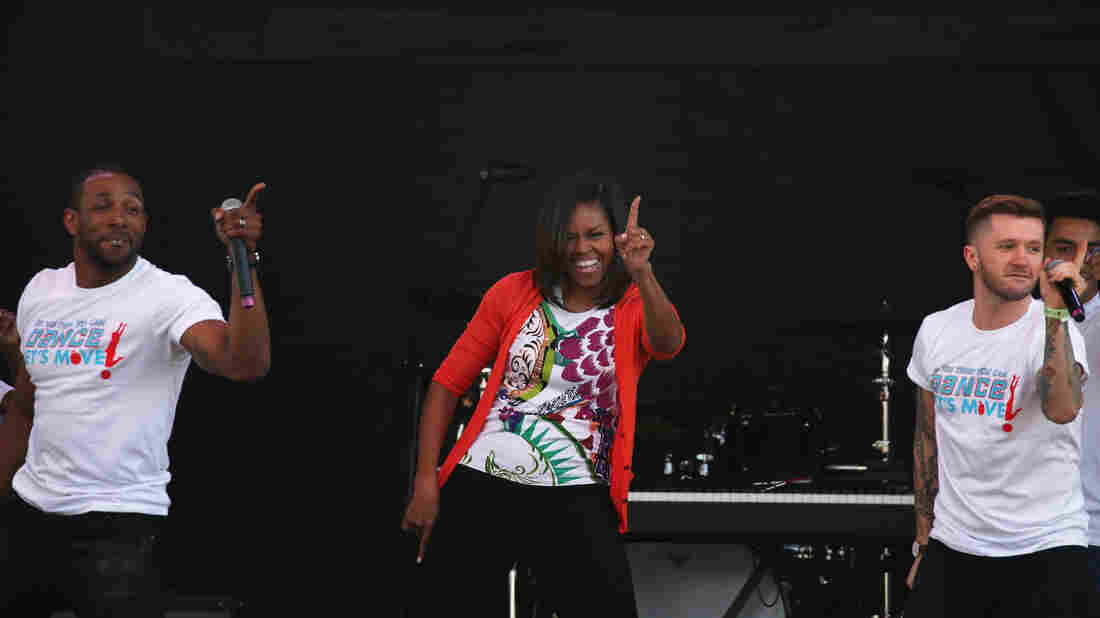

First Lady Michelle Obama wears her signature cardigan while dancing with performers from the television show So You Can Dance during the annual White House Easter Egg Roll on April 6, 2015. Mark Wilson/Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Ah, the cardigan: your granny’s cozy go-to used to be available year-round, but in limited quantities and colors. It was considered the sartorial equivalent of flossing: necessary, but not glamorous.

“The cardigan used to be something to keep you warm in the work place,” explains Teri Agins, who covered the fashion industry for the Wall Street Journal for years. “It was not really an accessory you left on—unless you wore it as part of a twin set.”

That look, sweater upon sweater, was considered too prim for a lot of young women. It was their mother’s look.

Enter Michelle Obama, and the game changed.

-

Hide captionPresident Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama walk along the Colonnade of the White House on Sept. 21, 2010. Michelle’s fashion choices have influenced designers’ profits.Pete Souza/White House

Hide captionPresident Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama walk along the Colonnade of the White House on Sept. 21, 2010. Michelle’s fashion choices have influenced designers’ profits.Pete Souza/White House -

Hide captionMichelle poses with the co-hosts of The View on June 18, 2008. Her dress from White House/Black Market sold out completely after her appearance on the show.Steve Fenn/ABC via Getty Images

Hide captionMichelle poses with the co-hosts of The View on June 18, 2008. Her dress from White House/Black Market sold out completely after her appearance on the show.Steve Fenn/ABC via Getty Images -

Hide captionThe Obamas hug after on day four of the Democratic National Convention in Denver on Aug. 28, 2008.Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Hide captionThe Obamas hug after on day four of the Democratic National Convention in Denver on Aug. 28, 2008.Mark Wilson/Getty Images -

Hide captionMichelle poses with Sarah Brown, the wife of British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, at 10 Downing Street, in London, on April 1, 2009. Her sweater sold out later that day.Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images

Hide captionMichelle poses with Sarah Brown, the wife of British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, at 10 Downing Street, in London, on April 1, 2009. Her sweater sold out later that day.Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images -

Hide captionThe First Lady and fashion designer Jason Wu stand next to the gown she wore to the inaugural balls at the Smithsonian Museum of American History on March 9, 2010 in Washington, D.C. Mrs. Obama continues a long tradition of first ladies who have donated their inaugural gown to be on display at the Smithsonian.Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Hide captionThe First Lady and fashion designer Jason Wu stand next to the gown she wore to the inaugural balls at the Smithsonian Museum of American History on March 9, 2010 in Washington, D.C. Mrs. Obama continues a long tradition of first ladies who have donated their inaugural gown to be on display at the Smithsonian.Mark Wilson/Getty Images -

Hide captionMichelle Obama takes the stage during the Democratic National Convention on Sept. 4, 2012 in Charlotte, N.C.Win McNamee/Getty Images

Hide captionMichelle Obama takes the stage during the Democratic National Convention on Sept. 4, 2012 in Charlotte, N.C.Win McNamee/Getty Images

1 of 6

“She wore cardigans with her sleeveless dresses, wore a lot of print dresses with solid cardigans,” Agins says. She even sometimes belted her sweaters to show off her trim waistline.

And she didn’t just wear the sweaters behind closed doors at 1600 Pennsylvania. For a March 2009 Vogue interview about her new job, she wore a papaya cashmere cardigan with a soft ruffled blouse. When the Obamas made their first official trip to England, she donned a jeweled cream silk cardigan over a pale green pencil skirt when she visited 10 Downing Street. The London-based international press noticed. IDTV described the effect this way: “Her upbeat ensemble stood out alongside the British Prime Minister’s wife’s navy outfit.”

That sweater, from mid-market retailer J. Crew, sold out within hours the same day photos of Mrs. O were released. The total cost of the sweater and skirt (also J. Crew) was $400.

Kim Kardashian’s every outfit may be chronicled by photographers, too, but you don’t see sales of her cut-down-to-there dresses or super-shredded jeans selling out after those photos are published. Kardashian is a celebrity, but she does not move markets in the same way. Most celebrities don’t.

Michelle Obama does, and it’s often her more casual clothes that cause bottom lines and stocks to soar. There are even numbers that prove it: David Yermack, a professor of finance at NYU’s Stern School of Business actually tracked Mrs. O’s looks for about a year in a study that was published in the Harvard Business Review. How This First Lady Moves Markets looked at 189 outfits Mrs. O wore to public events from November 2008 through December 2009 and eyeballed 30 publicly traded stocks from the businesses whose brands the first lady wore. Yermack says the findings surprised even him:

“It was truly remarkable how much more effect Mrs. Obama had on the commercial fashion industry that almost any other celebrity you could find in any other commercial setting,” Yermack says. And it wasn’t just a freak blip on the graph: “This would be a very permanent thing,” Yermack emphasized. “The stocks would not go down the next day. So to put a number on it for just a generic company at a routine event, it was worth about $38 million to have Mrs. Obama wear your clothes.”

Hel-lo.

The brands tracked in the Yermack study yielded $2.7 billion in the cumulative appreciation of stock prices. While J. Crew had some of the biggest gains, clothes from Target, The Gap and Liz Claiborne also did well when Mrs. Obama wore them. As did high-end clothes from companies like LVMH—which owns Louis Vuitton and Givenchy, among others— and Saks Fifth Ave.

Markets can go up or down, professional fashion observers can praise or pan her, but Mrs. Obama herself has always downplayed her fashion savvy. She told ABC’s Robin Roberts in 2008 she felt there was some pressure to represent, since her clothes (like many first ladies’) were so closely scrutinized. “It’s hard,” she admitted to Roberts. “I’m kind of a tomboy-jock at heart—but I like to look nice.”

She has been widely praised for using clothes to reflect her personality and the occasion, but she hasn’t been perfect. Some people thought the red-and black Narcisco Rodriguez dress she wore in election night in Chicago was a risk that didn’t work. And there was a slight misstep on vacation the first year, when the Obamas visited a national park during a heat wave and the first lady exited Air Force One in shorts. (Sensible, but an apparent protocol no-no.) And some people, including the late Oscar de la Renta, thought a sweater — even, apparently, a very expensive one by Azzedine Alaia — was a little too casual to wear for drinks with Queen Elizabeth. He told Women’s Wear Daily, “You don’t … go to Buckingham Palace in a sweater.” He was also critical of her decision to wear an Alexander McQueen gown to a state dinner in 2011. (De la Renta later softened his stance on Michelle Obama’s choices, saying, “she’s a great example to American women today.”)

But when FLOTUS got it right, she really got it right: the full-skirted dresses in bright prints she’s worn since day one. The simple sheaths in jewel tones. The sleeveless dresses and blouses. The flats. Those looks translated into sales.

And the cardigan:

“The sweater business traditionally would not be doing well in a time like this,” says Marshall Cohen, who analyzes retail fashion for the market research firm NPD. “However, there are certain styles within the category that are doing well.”

And it’s probably not coincidental that Michelle Obama has glamorized this once-mundane staple. Her way of dressing has resonated with American women, says Robin Givhan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning fashion critic for the Washington Post.

“One of the really vital things that Michelle Obama has done, is she’s wearing real fashion,” says Givhan, who covered the first lady for her first year in the White House. Mrs. Obama’s decision to wear consciously un-corporate looks, Givhan says, “was her own use of fashion as a way of defining who she was going to be in the White House.”

Mrs. Obama was going to continue being what she had been—a working wife and mother, wearing what she liked, what was comfortable and what worked for her. In doing that, Givhan says, the first lady was not so much initiating change as reflecting how women around the country already had begun to change their own look—dresses instead of suits, sweaters instead of jackets, bare legs instead of pantyhose. Those choices struck a plangent note.

“When Michelle Obama came along and made all these these things a matter of course,” Givhan says, “I think it validated a lot of things they were doing, and also validated things that they wanted to do but often felt they weren’t allowed to.”

Unlike style, fashion used to be restricted to a fairly small group: the young, the thin, the wealthy … and the white. Michelle Obama broadened the serious fashionista membership, says Teri Agins. And not just in dress size and economic status.

Besides Oprah, “we haven’t seen many middle-aged, brown-skinned women who have been celebrated for their beauty and style.”

And for decades, we haven’t seen women of any race or age who have been able to make cash registers ring simply by stepping out the front door.

Safe to say the fashion industry is going to miss this Obama Effect.