Dr. Odontuya Davaasuren has one goal: to improve the way people die in Mongolia.

“My father died of lung cancer, my mother died, my mother-in-law died because of liver cancer,” she says. “Even though I was a doctor, I could do nothing.”

The feeling of helplessness, and the unnecessary pain her relatives suffered, is what Davaasuren has set out to fix. She has white hair because of it, says the family doctor and professor at the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences in Ulaanbaatar. “It’s very hard work.”

Her efforts have earned her the title “the mother of palliative care in Mongolia.” And they’ve transformed the way people die.

In global rankings on quality of death released this fall by the Economist Intelligence Unit, Mongolia stood out. It’s number 28 on the list. “Some countries with lower income levels demonstrate the power of innovation and individual initiative,” the report noted, citing Mongolia for “rapid growth in hospice facilities and teaching programs.”

That’s no small feat, regardless of a country’s income level. Palliative care is a relatively new field. Funding tends to go toward combating infectious diseases, rather than towards easing the pain for those who have incurable illness. Hospitals might not want to consider offering hospice care, because it would simply increase the number of deaths that happen on their watch. And globally, doctors and law enforcement officers fear morphine, which happens to be one of the cheapest and most effective painkillers.

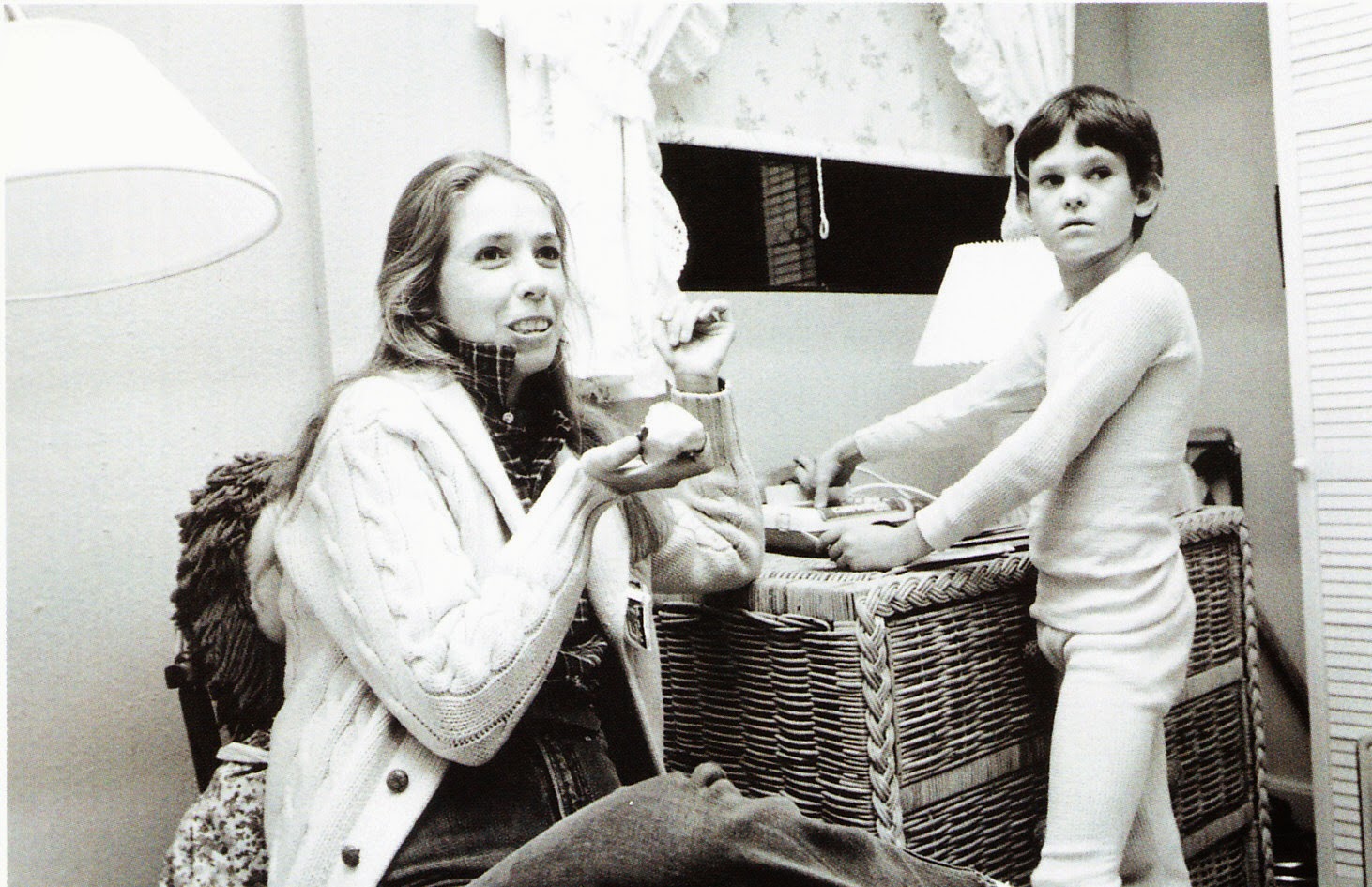

Dr. Odontuya Davaasuren, right, says that a good death is “being comfortable, being with loved people, listening to good words. Even an unconscious person listens, because hearing stops last.” Courtesy Odontuya Davaasuren hide caption

itoggle caption Courtesy Odontuya Davaasuren

Most Mongolians die from noncommunicable illnesses like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. The country is huge and sparsely populated, so most people die at home. About a third of the population lives under the poverty line. The monthly salary of a nurse is around $100. But the progress on end-of-life care that Mongolia has made contrast sharply to the situation in neighboring Russia, a country with some of the most restrictive drug regulations, and where Human Rights Watch says the government has barred journalists from reporting on suicide committed by cancer patients in severe pain.

In Mongolia, as in many other countries, there used to be two options for terminally ill people on their deathbeds: stay at home or go to the intensive care unit, or ICU. A bad death, Davaasuren says, is to die in the ICU, connected to machines, alone, watching the white hospital ceiling, and getting lab tests every few hours. “In the intensive care unit, patients are swaddled by machines and tubes. It’s a stupid death. It’s a really bad death,” she says.

American surgeon and writer Dr. Atul Gawande agrees. Even in the U.S., he writes in his best-seller Being Mortal, “You don’t have to spend much time with the elderly or those with terminal illness to see how often medicine fails the people it is supposed to help. The waning days of our lives are given over to treatments that addle our brains and sap our bodies for a sliver’s chance of benefit. These days are spent in institutions — nursing homes and intensive-care units — where regimented, anonymous routines cut us off from all the things that matter to us in life.”

In the ICU, says Davaasuren, “even if all signs show that the patient will die,” all kinds of tests and treatments are given in the name of survival, even if it dims the quality of life. It used to be that the only alternative was to die at home, sometimes in pain. But a good death, says Davaasuren, is “being comfortable, being with loved people, listening to good words. Even an unconscious person listens, because hearing stops last.”

Davaasuren first learned about palliative care in Sweden in 2000.

Back then, she says, there wasn’t even terminology for palliative care in her country. She’s now the president of the Mongolian Palliative Care Society and has worked to change things.

After the conference in Sweden, she and her students visited patients with severe diagnoses and filmed their conversations. “During these visits I saw so much suffering, so many problems. Not just physical pain – psychological problems, financial problems, spiritual,” she says. A woman with two small children had such severe pain she asked to die. A man in his 30s committed suicide when he was left in unbearable pain after his allotted two-day supply of morphine was up. Families spent fortunes, she says, in search of alternative treatment and medication. “They went to Korea, went to China, looking for better treatment,” she says.

Davaasuren eventually spoke on national TV in the early 2000s about the lack of palliative care in Mongolia, saying that according to WHO recommendations Mongolia was in need of 150 palliative care beds. It had zero. “I had very strong words to the Ministry of Health,” she says.

“When I started to talk about it, many people in the Ministry of Health told me ‘What are you talking about? We have no money for living patients, why do you want to spend money for dying patients?” she says.

Bit by bit, she and her colleagues have managed to turn the tide. Davaasuren and her colleagues translated international publications on palliative care into Mongolian. A grant in 2004 from the Open Society Foundation helped them start courses for nurses and doctors. They worked to change prescription rules so that suffering patients could get cheap painkillers. She brought a hospice doctor from California and a hospice nurse from Virginia to train health workers on palliative care.

Now, poor families taking care of a terminally ill person can get about 36,000 tugrik [$18] each month from the government until the patient dies. “It’s very small but still supportive,” says Davaasuren.

“Before in Mongolia we had the wrong drug regulation,” she says. It used to be that only oncologists could prescribe morphine, and they could give a maximum of ten doses to a patient. Studies on cancer patients before 2000 found that they often died within a month after getting the painkillers – and the incorrect assumption was that the morphine killed them, says Davaasuren.

The country started importing oral morphine tablets in 2006. There is now one pharmacy in each of Mongolia’s 21 provinces with the right to distribute opioids. Before, there was only one. (Because of international regulations, the drugs have to be kept locked up and under security camera surveillance.) At least two people in each province – usually a family doctor and a nurse who are trained in palliative care – can prescribe opioids. “Now oncologists, family doctors have the right to prescribe opioids according to the patient’s needs, every seven days until death,” she says.

In 2000, writes Davaasuren, Mongolia as a whole only used two pounds of morphine a year. By 2004, it was 13 pounds. Last year, according to the Ministry of Health, the country imported a combined 48 pounds of opioid painkillers. A Mongolian company now produces morphine, codeine and pethidine and will this year start producing oxycodone.

There are about 60 beds designated for palliative care in the capital alone. Last month, the Ministry of Health signed off on plans to provide 596 palliative care beds across the country by 2017. The goal now, says Davaasuren, is to extend palliative care to non-cancer patients and to terminally ill children — and to redefine a good death as a success. “Hospitals don’t like to have palliative care patients because if patients die, it increases the death rate in their hospital,” she says. She’s working to get palliative care deaths registered outside of the hospital system.

Davaasuren continues to teach courses to medical students on topics like pain management and how to break bad news. Because sooner or later, she says, “each family will face this problem.”

“Mongolian people say we have one truth,” she adds. “If we are born on this earth, we will die one day.”

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.