Williams Sisters Both Win Easily; Set Up U.S. Open Quarterfinal

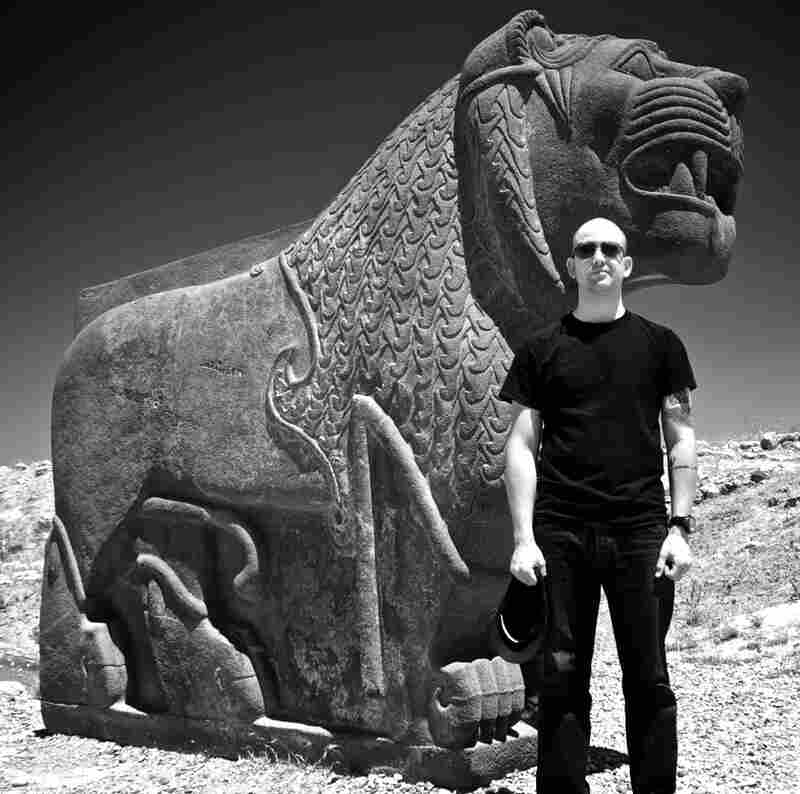

Serena Williams serves to Madison Keys during their Women’s Singles Fourth Round match on Day 7 of the 2015 U.S. Open. Serena will play her sister Venus in the tournament’s quarterfinals. Chris Trotman/Getty Images hide caption

itoggle caption Chris Trotman/Getty Images

No need for any extra practice for Serena Williams after this performance.

Plus, it’s not as if she needs to study too hard to figure out how to deal with her next opponent.

Playing far better than she did earlier in the U.S. Open as she chases a calendar-year Grand Slam, Williams set up a quarterfinal against older sister Venus with a 6-3, 6-3 victory over 19th-seeded Madison Keys on Sunday.

“A Williams will be in the semis, so that’s good,” the No. 1-seeded Serena said after needing only 68 minutes to dismiss Keys, a 20-year-old American with formidable serves and forehands who simply was outplayed.

Already a winner of the past four major tournaments, including last year’s U.S. Open, Serena is trying to become the first tennis player to win all four Grand Slam titles in the same season since Steffi Graf in 1988.

Venus, at 35 the oldest woman to enter the field, was on court even less time than her sibling, overwhelming 19-year-old qualifier Anett Kontaveit of Estonia 6-2, 6-1.

Venus’ match came first in Arthur Ashe Stadium, so then she had to decide whether to watch Serena play.

“I get very nervous, because even if I have to play Serena, I still want her to win, so I have a hard time watching unless she’s winning. Then it’s easy to watch,” said Venus, who won U.S. Open titles in 2000 and 2001, but had lost in the third round or earlier each of the past four years. “So it depends on how my nerves are.”

Serena acknowledged having a bout with the jitters before her second-round match, when she double-faulted 10 times, made another two dozen unforced errors and needed to come back over and over just to claim the opening set against a qualifier ranked 110th. Afterward, she took pointers from coach Patrick Mouratoglou and headed out to the practice court right away.

Then, in the third round, against someone ranked 101st, Serena dropped the first set and was two games from defeat in the second before turning things around. Again, she put in more work to fix things.

“I’m so proud that I was able to serve a lot better. Obviously I had to,” she said after winning 22 of 28 first-serve points and never facing a break point against Keys. “I was like, ‘Serena, it’s now or never. You’ve got to get that serve together.'”

As for whether she’d need to head out for a training session with Mouratoglou this time, Serena said: “No, not today. I’m going to take the rest of the day off and relax and just enjoy it.”

Another women’s fourth-round match scheduled for Sunday was scratched when 25th-seeded Eugenie Bouchard withdrew with a concussion, two days after slipping and falling in the locker room. The 21-year-old Canadian, the runner-up at Wimbledon last year, was supposed to play Roberta Vinci of Italy.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.